Chapter 3 The Skin

Basic Terminology and Diagnostic Techniques

1 How many skin diseases exist? What are the two main categories of skin lesions?

There are more than 1400 skin diseases. Yet, only 30 are important, common, and worth knowing. The first step toward their recognition is the separation of primary from secondary lesions (Table 3-1).

Primary lesions result only from disease and have not been changed by additional events (such as trauma, scratching, or medical treatment; see Table 3-1). To better identify primary lesions, pay attention to their colors, shape, arrangement, and distribution.

Primary lesions result only from disease and have not been changed by additional events (such as trauma, scratching, or medical treatment; see Table 3-1). To better identify primary lesions, pay attention to their colors, shape, arrangement, and distribution.

Secondary lesions instead have been altered by outside manipulation, medical treatment, or their own natural course.

Secondary lesions instead have been altered by outside manipulation, medical treatment, or their own natural course.

Table 3-1 Dermatologic Lesions

| skin lesions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Special |

| Solid (Nonpalpable) | Crusts | Purpurae |

| • Macules (≤0.5 cm) | Scales | Petechiae |

| • Patches (>0.5 cm) | Ulcers | Ecchymoses |

| Fissures | Teleangiectasias | |

| Solid (Palpable) | Excorations | Comedones |

| • Papules (≤0.5 cm) | Scars | Burrows |

| • Plaques (>0.5 cm) | Erosions | Target lesions |

| • Nodules (deeper plaques) | Lichenification | |

| • Wheals (pruritic plaques) | Atrophy | |

| • Tumors (larger nodules) | Scars | |

| Sinuses | ||

| Fluid-Lesions | ||

| • Vesicles (fluid-filled papules) | ||

| • Pustules (pus-filled papules) | ||

| • Bullae (fluid-filled plaques) | ||

| • Cysts (fluid-filled nodules) | ||

2 What are the major primary lesions?

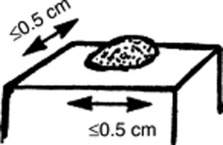

Macules: Flat, nonpalpable, circumscribed areas of discoloration ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical macules are the familiar freckles.

Macules: Flat, nonpalpable, circumscribed areas of discoloration ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical macules are the familiar freckles.

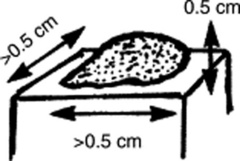

Patches: Flat, nonpalpable areas of skin discoloration >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large macule). A typical patch is the one of vitiligo.

Patches: Flat, nonpalpable areas of skin discoloration >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large macule). A typical patch is the one of vitiligo.

Papules: Raised and palpable lesions ≤0.5 cm in diameter. They may or may not have a different color from the surrounding skin. A typical papule is a raised nevus.

Papules: Raised and palpable lesions ≤0.5 cm in diameter. They may or may not have a different color from the surrounding skin. A typical papule is a raised nevus.

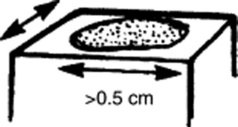

Plaques: Raised and palpable lesions >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large papule). Usually confined to the superficial dermis, they may result from the confluence of papules. A typical plaque is that of psoriasis.

Plaques: Raised and palpable lesions >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e., a large papule). Usually confined to the superficial dermis, they may result from the confluence of papules. A typical plaque is that of psoriasis.

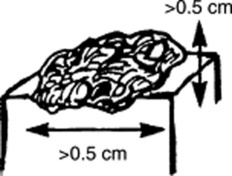

Nodules: Raised, palpable, and elevated lesions >0.5 cm in diameter, which, unlike plaques, go deeper into the dermis. Since they are below the surface of the skin, the overlying cutis is usually mobile. Typical nodules are those of erythema nodosum.

Nodules: Raised, palpable, and elevated lesions >0.5 cm in diameter, which, unlike plaques, go deeper into the dermis. Since they are below the surface of the skin, the overlying cutis is usually mobile. Typical nodules are those of erythema nodosum.

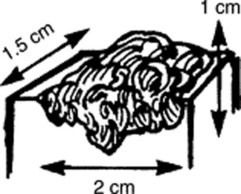

Tumors: Nodules that are either >2 cm in diameter or poorly demarcated. Usually neoplastic.

Tumors: Nodules that are either >2 cm in diameter or poorly demarcated. Usually neoplastic.

Wheals (hives): Raised, circumscribed, edematous, and typically pruritic plaques that are pink or pale but typically transient. Classic wheals are the lesions of urticaria, or of a mosquito bite.

Wheals (hives): Raised, circumscribed, edematous, and typically pruritic plaques that are pink or pale but typically transient. Classic wheals are the lesions of urticaria, or of a mosquito bite.

Vesicles (blisters): Fluid-filled, circumscribed, and raised lesions that contain clear serous fluid and are ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical vesicles are those of herpes simplex.

Vesicles (blisters): Fluid-filled, circumscribed, and raised lesions that contain clear serous fluid and are ≤0.5 cm in diameter. Typical vesicles are those of herpes simplex.

Bullae: Vesicles >0.5 cm in diameter. Commonly seen in patients with second-degree burns. Presence of a bulla is so important that it usually trumps all other concomitant primary lesions.

Bullae: Vesicles >0.5 cm in diameter. Commonly seen in patients with second-degree burns. Presence of a bulla is so important that it usually trumps all other concomitant primary lesions.

Cysts: Raised and encapsulated lesions that contain fluid or semi-solid material. Typical are the cysts of acne.

Cysts: Raised and encapsulated lesions that contain fluid or semi-solid material. Typical are the cysts of acne.

Pustules: Pus-filled papules. Typically seen in patients with impetigo or acne.

Pustules: Pus-filled papules. Typically seen in patients with impetigo or acne.

Purpura: Skin extravasation of red cells, which, based on size, may present as petechiae or ecchymoses. Palpable purpura is never normal and argues for an antigen-antibody complex (vasculitis). Often localized to the lower extremities, the lesions of Henoch-Schönlein are typical examples of a palpable purpura. Internal organs (kidneys, GI tract) are often involved too.

Purpura: Skin extravasation of red cells, which, based on size, may present as petechiae or ecchymoses. Palpable purpura is never normal and argues for an antigen-antibody complex (vasculitis). Often localized to the lower extremities, the lesions of Henoch-Schönlein are typical examples of a palpable purpura. Internal organs (kidneys, GI tract) are often involved too.

Petechiae: Reddish-to-purple discolorations, caused by a microscopic hemorrhage. These are <0.5 cm in diameter and usually in clusters. With the exception of color, they resemble papules or macules (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typical petechiae are those of typhus. The lesions of thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura (TTP) are typical petechiae too.

Petechiae: Reddish-to-purple discolorations, caused by a microscopic hemorrhage. These are <0.5 cm in diameter and usually in clusters. With the exception of color, they resemble papules or macules (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typical petechiae are those of typhus. The lesions of thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura (TTP) are typical petechiae too.

Ecchymoses (bruises): Reddish-to-purple discolorations larger than petechiae. Except for color, they resemble plaques and patches (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typically located below an intact epithelial surface.

Ecchymoses (bruises): Reddish-to-purple discolorations larger than petechiae. Except for color, they resemble plaques and patches (depending on whether they are palpable or not). Typically located below an intact epithelial surface.

Spider angiomas: These are arterial teleangiectasias, i.e., vascular arterial lesions that resemble the legs of a spider. They fill from the center and blanch whenever this is compressed.

Spider angiomas: These are arterial teleangiectasias, i.e., vascular arterial lesions that resemble the legs of a spider. They fill from the center and blanch whenever this is compressed.

Venous spiders: These are venousteleangiectasias, i.e., vascular venous lesions that also resemble the legs of a spider. Hence, they fill from the periphery, not the center. They empty with pressure.

Venous spiders: These are venousteleangiectasias, i.e., vascular venous lesions that also resemble the legs of a spider. Hence, they fill from the periphery, not the center. They empty with pressure.

3 What are the major secondary lesions?

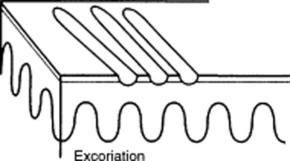

Excoriations: Linear erosions produced by scratching. Often raised, scratch marks may also present as crust on top of a primary lesion that has been partially scratched off. They are almost exclusively confined to the eczematous diseases.

Excoriations: Linear erosions produced by scratching. Often raised, scratch marks may also present as crust on top of a primary lesion that has been partially scratched off. They are almost exclusively confined to the eczematous diseases.

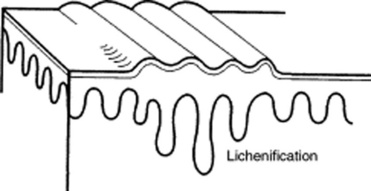

Lichenification: A typical skin thickening seen in chronic pruritus with recurrent scratching. Resembles the callus formation of palms and soles after recurrent trauma. Lichenified skin is hardened, leather-like, with prominent markings and some scaling. Like excoriation, lichenification is typical of eczematous diseases. In fact, it is considered pathognomonic of atopic dermatitis.

Lichenification: A typical skin thickening seen in chronic pruritus with recurrent scratching. Resembles the callus formation of palms and soles after recurrent trauma. Lichenified skin is hardened, leather-like, with prominent markings and some scaling. Like excoriation, lichenification is typical of eczematous diseases. In fact, it is considered pathognomonic of atopic dermatitis.

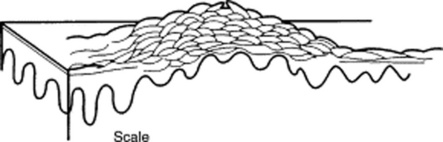

Scales: Raised lesions presenting as flaking of the upper skin surface. In fact, they represent thickening of the stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of the epidermis. Scales may be white, gray, or tan. They may also be small or rather large. They provide the squamous component to papulosquamous diseases. They are extremely common in the scalp, where they suggest either banal processes (dandruff) or more serious conditions (seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea capitis).

Scales: Raised lesions presenting as flaking of the upper skin surface. In fact, they represent thickening of the stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of the epidermis. Scales may be white, gray, or tan. They may also be small or rather large. They provide the squamous component to papulosquamous diseases. They are extremely common in the scalp, where they suggest either banal processes (dandruff) or more serious conditions (seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea capitis).

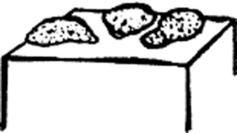

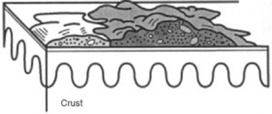

Crusts: Raised lesions produced by dried serum and blood cell remnants. Usually preceded by fluid-filled primary lesions (i.e., vesicles, pustules, or bullae). The most familiar crust is the “scab” of impetigo.

Crusts: Raised lesions produced by dried serum and blood cell remnants. Usually preceded by fluid-filled primary lesions (i.e., vesicles, pustules, or bullae). The most familiar crust is the “scab” of impetigo.

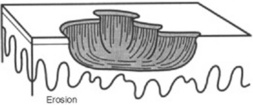

Erosions: Depressed lesions produced whenever the epidermis is either removed or sloughed. They are moist, usually red, and well circumscribed. Classic erosions are those of chickenpox following rupture of a vesicle.

Erosions: Depressed lesions produced whenever the epidermis is either removed or sloughed. They are moist, usually red, and well circumscribed. Classic erosions are those of chickenpox following rupture of a vesicle.

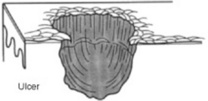

Ulcers: Depressed lesions produced whenever not only the epidermis but also part (or all) of the dermis is gone. Ulcers are concave, often moist, and at times inflamed or even hemorrhagic. They heal with scarring. A classic ulcer is that of the syphilitic chancre.

Ulcers: Depressed lesions produced whenever not only the epidermis but also part (or all) of the dermis is gone. Ulcers are concave, often moist, and at times inflamed or even hemorrhagic. They heal with scarring. A classic ulcer is that of the syphilitic chancre.

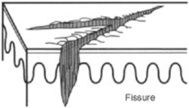

Fissures: Depressed lesions presenting as narrow, linear, and vertical cracks that penetrate through the epidermis, reaching at least part of the dermis. Classic fissures are those of the athlete’s foot.

Fissures: Depressed lesions presenting as narrow, linear, and vertical cracks that penetrate through the epidermis, reaching at least part of the dermis. Classic fissures are those of the athlete’s foot.

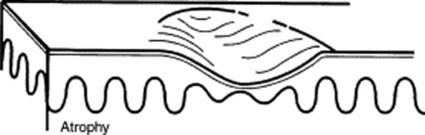

Atrophy: Usually the nonspecific end-product of various skin disorders. It is characterized by a pale and shiny area, with loss of cutaneous markings and full skin thickness.

Atrophy: Usually the nonspecific end-product of various skin disorders. It is characterized by a pale and shiny area, with loss of cutaneous markings and full skin thickness.

Sinuses: Connective channels between the surface of the skin and deeper components.

Sinuses: Connective channels between the surface of the skin and deeper components.

4 Are there other ways to classify skin lesions?

Many ways. One divides lesions into four groups based on the relationship with the surrounding skin:

6 What is the configuration of a skin lesion?

It is the outline of the lesion as observed from above. The most common configurations are:

Annular: Doughnut-shaped lesions. Fungal infections present as red rings with the scaly surface.

Annular: Doughnut-shaped lesions. Fungal infections present as red rings with the scaly surface.

Linear: Lesions arranged in a line. For example, streaks of small vesicles on an erythematous base. The most common linear lesion is the rash of poison ivy, also called rhus dermatitis (rhus is the Greek word for sumac, which describes various shrubs or small trees). Some species of sumac, or rhus, include poison ivy and poison oak—both cause an acute itching rash on contact.

Linear: Lesions arranged in a line. For example, streaks of small vesicles on an erythematous base. The most common linear lesion is the rash of poison ivy, also called rhus dermatitis (rhus is the Greek word for sumac, which describes various shrubs or small trees). Some species of sumac, or rhus, include poison ivy and poison oak—both cause an acute itching rash on contact.

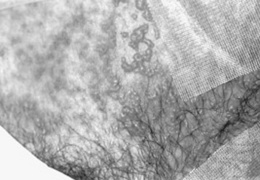

Reticular: Lesions organized in a net-like cluster

Reticular: Lesions organized in a net-like cluster

Gyrate: Lesions with a serpiginous (or polycyclic) configuration—as in gyrate erythema

Gyrate: Lesions with a serpiginous (or polycyclic) configuration—as in gyrate erythema

9 And so, what are the required components of a dermatologic diagnosis?

Morphology: Color, shape, dimensions (width and height, if necessary), elevation/depression, and palpable features (smoothness, induration, tenderness, scaling, and crusting)

Morphology: Color, shape, dimensions (width and height, if necessary), elevation/depression, and palpable features (smoothness, induration, tenderness, scaling, and crusting)

Distribution (body location): Generalized versus localized

Distribution (body location): Generalized versus localized

Distribution (arrangement to one another): Clustered, confluent, dermatomal

Distribution (arrangement to one another): Clustered, confluent, dermatomal

10 What are the tools necessary for a dermatologic diagnosis?

Wood’s lamp: A fluorescent and long-wave ultraviolet light that has been narrowed to 360 nm. Developed by Robert Wood (1868–1955), it is commonly relied on for detecting fungal lesions, areas of hypopigmentation, and porphyrin compounds. In a darkened room, it reveals fungal infections (like tinea capitis) as sharply marginated patches of bright blue-green. Since melanin absorption is at 360 nm, it also identifies areas of vitiligo or tinea versicolor (hypopigmented patches as pale-white, and depigmented areas as bright-white). Finally, it makes porphyrin compounds stand out as coral red fluorescence, like in erythrasma, a bacterial infection of intertriginous areas (axillae).

Wood’s lamp: A fluorescent and long-wave ultraviolet light that has been narrowed to 360 nm. Developed by Robert Wood (1868–1955), it is commonly relied on for detecting fungal lesions, areas of hypopigmentation, and porphyrin compounds. In a darkened room, it reveals fungal infections (like tinea capitis) as sharply marginated patches of bright blue-green. Since melanin absorption is at 360 nm, it also identifies areas of vitiligo or tinea versicolor (hypopigmented patches as pale-white, and depigmented areas as bright-white). Finally, it makes porphyrin compounds stand out as coral red fluorescence, like in erythrasma, a bacterial infection of intertriginous areas (axillae).

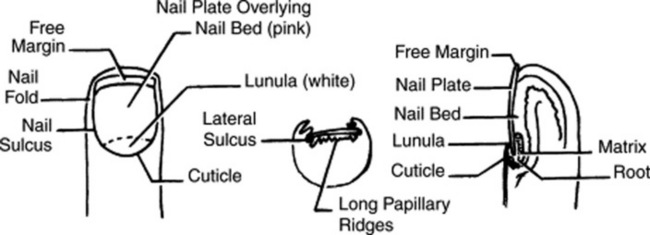

14 How should fingernails and toenails be assessed?

If covered by polish, clean them first with a solvent like acetone. Then pay attention to color and shape but also to anatomic details (Fig. 3-25):

Lunula: The white half-moon at the proximal edge of the nail bed

Lunula: The white half-moon at the proximal edge of the nail bed

Cuticle: The thin skin adherent to the nail at its proximal portion

Cuticle: The thin skin adherent to the nail at its proximal portion

Perionychium: The epidermis forming the ungual wall at the sides and back of the nail

Perionychium: The epidermis forming the ungual wall at the sides and back of the nail

15 What systemic conditions are associated with changes in nail shape or growth?

Clubbing: Inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary malignancy, asbestosis, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, congenital heart disease, endocarditis, atrioventricular malformation and fistulas (see also question 19)

Clubbing: Inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary malignancy, asbestosis, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, congenital heart disease, endocarditis, atrioventricular malformation and fistulas (see also question 19)

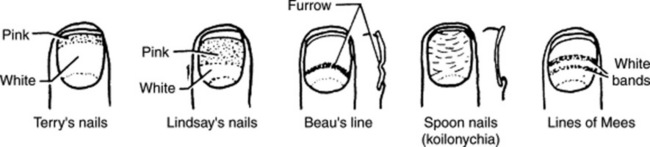

Koilonychia (spoon nails) (Fig. 3-26): Iron deficiency anemia, hemochromatosis, Raynaud’s disease, systemic lupus disease, trauma, nail-patella syndrome

Koilonychia (spoon nails) (Fig. 3-26): Iron deficiency anemia, hemochromatosis, Raynaud’s disease, systemic lupus disease, trauma, nail-patella syndrome

Onycholysis: Psoriasis, infection, hyperthyroidism, sarcoidosis, trauma, amyloidosis, connective tissue disorders

Onycholysis: Psoriasis, infection, hyperthyroidism, sarcoidosis, trauma, amyloidosis, connective tissue disorders

Pitting: Psoriasis, Reiter’s syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, alopecia areata

Pitting: Psoriasis, Reiter’s syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti, alopecia areata

Beau’s lines (see Fig. 3-26): Any severe systemic illness that disrupts nail growth, Raynaud’s disease, pemphigus, trauma

Beau’s lines (see Fig. 3-26): Any severe systemic illness that disrupts nail growth, Raynaud’s disease, pemphigus, trauma

Yellow nail: Lymphedema, pleural effusion, immunodeficiency, bronchiectasis, sinusitis, rheumatoid arthritis, nephrotic syndrome, thyroiditis, tuberculosis, Raynaud’s disease

Yellow nail: Lymphedema, pleural effusion, immunodeficiency, bronchiectasis, sinusitis, rheumatoid arthritis, nephrotic syndrome, thyroiditis, tuberculosis, Raynaud’s disease

16 What systemic conditions are associated with changes in nail color?

Terry’s nails (see Fig. 3-26): Hepatic failure, cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, malnutrition

Terry’s nails (see Fig. 3-26): Hepatic failure, cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, malnutrition

Azure lunula: Wilson’s disease, silver poisoning, quinacrine

Azure lunula: Wilson’s disease, silver poisoning, quinacrine

Lindsay’s nails (half-and-half nails) (see Fig. 3-26): Specific for renal failure

Lindsay’s nails (half-and-half nails) (see Fig. 3-26): Specific for renal failure

Muehrcke’s lines: Specific for hypoalbuminemia

Muehrcke’s lines: Specific for hypoalbuminemia

Lines of Mees’ (see Fig. 3-26): Arsenic poisoning, Hodgkin’s disease, congestive heart failure, leprosy, malaria, chemotherapy, carbon monoxide poisoning, other systemic insults

Lines of Mees’ (see Fig. 3-26): Arsenic poisoning, Hodgkin’s disease, congestive heart failure, leprosy, malaria, chemotherapy, carbon monoxide poisoning, other systemic insults

Dark longitudinal streaks: Melanoma, benign nevus, chemical staining, normal variant in darkly pigmented people

Dark longitudinal streaks: Melanoma, benign nevus, chemical staining, normal variant in darkly pigmented people

Longitudinal striations: Alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis

Longitudinal striations: Alopecia areata, vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis

Splinter hemorrhage: Subacute bacterial endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, malignancies, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, psoriasis, trauma

Splinter hemorrhage: Subacute bacterial endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, malignancies, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, psoriasis, trauma

Telangiectasia: Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma

Telangiectasia: Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma

Nails

19 What is clubbing?

A condition that can be (1) idiopathic; (2) congenital (dominant trait); or (3) a clue to serious underlying pathology, including cardiovascular, hepatobiliary, mediastinal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, neoplastic, infectious, and, especially, pulmonary (see Chapter 13, questions 101–116).

22 What are the nail findings of psoriasis?

Pitting (previously discussed)

Pitting (previously discussed)

Oil spot or salmon patch/nail bed: The most diagnostic nail sign; it consists of a translucent, yellow-red discolored patch in the nail bed, resembling a drop of oil beneath the plate.

Oil spot or salmon patch/nail bed: The most diagnostic nail sign; it consists of a translucent, yellow-red discolored patch in the nail bed, resembling a drop of oil beneath the plate.

Beau’s lines in the proximal nail matrix (see later)

Beau’s lines in the proximal nail matrix (see later)

Leukonychia: Areas of white nail plate; due to parakeratotic foci in the mid-matrix

Leukonychia: Areas of white nail plate; due to parakeratotic foci in the mid-matrix

Subungual hyperkeratosis: Excessive proliferation of the nail bed that can lead to onycholysis

Subungual hyperkeratosis: Excessive proliferation of the nail bed that can lead to onycholysis

Nail plate crumbling: Weakened nail plate, bed, and matrix from diseased underlying structures

Nail plate crumbling: Weakened nail plate, bed, and matrix from diseased underlying structures

Splinter hemorrhages: Longitudinal black lines due to tiny capillary hemorrhages between the nail bed and plate; analogous to Auspitz sign (pinpoint bleeding under the psoriatic plaque)

Splinter hemorrhages: Longitudinal black lines due to tiny capillary hemorrhages between the nail bed and plate; analogous to Auspitz sign (pinpoint bleeding under the psoriatic plaque)

Dilated tortuous capillaries in the dermal papillae

Dilated tortuous capillaries in the dermal papillae

Spotted lunula: Distal matrix involvement characterized by erythema of the lunula

Spotted lunula: Distal matrix involvement characterized by erythema of the lunula

26 What is longitudinal ridging (Reedy nails)?

A normal variant of patients older than 50, but one that also can occur in younger subjects. It may even represent a brittle nail variation. Ridges typically extend from the proximal nail fold to the distal plate, with some being very prominent, especially in older women. They are usually multiple, but at times may be single—like in patients with lichen planus (see questions 38 and 210–216).

38 What is lichen planus of the nail?

A condition present in 10% of patients with lichen planus. The most common finding is thinning of the nail plate, leading to longitudinal grooving and ridging (see also question 26). Hyperpigmentation, subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and longitudinal melanonychia can also be present.

41 What are azure half-moons in nail beds?

The nails of Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration). Lunulae are not white, but bluish.

48 What is paronychia?

An acute or chronic inflammation of the perionychium, with redness, swelling, and tenderness.

Fluid-Filled Lesions: PUS (Pustules)—Table 3-2

Acne

54 What does acne look like?

Table 3-2 Fluid-Filled lesions

| Fluid-Filled Lesions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pus-Filled | Clear Fluid | |

| Pustular | Vesiculo-Bullous | Bullous |

| Acne vulgaris | H. simplex | Pemphygus vulgaris |

| Acne rosacea | H. zoster/varicella | Pemphygoid |

| Steroid acne | Dermatophytoses | Drug reactions |

| • Erythema multiforme | ||

| • Stevens-Johnson | ||

| • TEN | ||

| Folliculitis (bacterial/fungal) | Insect bites | Poison ivy/contact dermatitis |

| Intertriginous candidiasis | Dermatitis herpetiformis | Bullous impetigo |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | ||

| Lupus erythematosus | ||

Fluid-Filled Lesions: Clear Fluid (Vesiculobullous Diseases)

62 What is the typical clinical course of herpes simplex?

Primary (initial) outbreaks: Usually more severe, with pain, edema, and a prolonged course. Still, the majority of primary infections go unnoticed because symptoms are either absent or so minimal that only the recurrent episodes are recognized.

Primary (initial) outbreaks: Usually more severe, with pain, edema, and a prolonged course. Still, the majority of primary infections go unnoticed because symptoms are either absent or so minimal that only the recurrent episodes are recognized.

Secondary (recurrent) disease: Less severe and shorter in duration. In fact, the hallmark of mucocutaneous herpes simplex is its ability to remain dormant in ganglia, eventually recurring in areas of primary infection. Frequency of recurrences varies, but for genital and labial herpes, the average is four episodes per year. Approximately 50% of patients with genital herpes have one or more episodes, often from local trauma, menses, and even stress.

Secondary (recurrent) disease: Less severe and shorter in duration. In fact, the hallmark of mucocutaneous herpes simplex is its ability to remain dormant in ganglia, eventually recurring in areas of primary infection. Frequency of recurrences varies, but for genital and labial herpes, the average is four episodes per year. Approximately 50% of patients with genital herpes have one or more episodes, often from local trauma, menses, and even stress.

63 What are the other clinical presentations of herpes simplex?

Herpetic gingivostomatitis: Presents in children and young adults with fever, malaise, sore throat, painful vesicles, and erosions of tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips

Herpetic gingivostomatitis: Presents in children and young adults with fever, malaise, sore throat, painful vesicles, and erosions of tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips

Herpetic whitlow (middle English for white flaw; also referred to as a felon): This is an occupational hazard of medical and dental professionals caused by exposure to the virus in a patient’s mouth. It is characterized by vesicles and edema of a digit, sometimes associated with erythema, lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy of the arm. It may last for several weeks.

Herpetic whitlow (middle English for white flaw; also referred to as a felon): This is an occupational hazard of medical and dental professionals caused by exposure to the virus in a patient’s mouth. It is characterized by vesicles and edema of a digit, sometimes associated with erythema, lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy of the arm. It may last for several weeks.

Herpes simplex in immunosuppressed patients: Frequently produces more severe and persistent ulceration, as well as disseminated cutaneous and systemic lesions

Herpes simplex in immunosuppressed patients: Frequently produces more severe and persistent ulceration, as well as disseminated cutaneous and systemic lesions

66 Who develops varicella?

Mostly children younger than 10 years. Only 5% of cases occur in subjects older than 15.

73 What are the other presentations of herpes zoster?

Involvement of the eye (ophthalmic branch): Heraldic lesions appear on the tip of the nose, due to infection of the nasociliary nerve. Get immediate ophthalmologic consultation.

Involvement of the eye (ophthalmic branch): Heraldic lesions appear on the tip of the nose, due to infection of the nasociliary nerve. Get immediate ophthalmologic consultation.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome: Due to involvement of the geniculate ganglion with facial paralysis. Lesions occur over the external auditory canal or tympanic membrane, with or without vertigo, tinnitus, deafness/hyperacusis, unilateral loss of taste, and decrease in tear formation and salivation. Described by the Philadelphia neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874–1937).

Ramsay Hunt syndrome: Due to involvement of the geniculate ganglion with facial paralysis. Lesions occur over the external auditory canal or tympanic membrane, with or without vertigo, tinnitus, deafness/hyperacusis, unilateral loss of taste, and decrease in tear formation and salivation. Described by the Philadelphia neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874–1937).

Zoster in immunocompromised patients: Seen in patients with AIDS and malignancies (especially lymphocytic leukemia or Hodgkin’s) and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Usually more severe and often disseminated. Chronic eruptions can be the first sign of HIV infection.

Zoster in immunocompromised patients: Seen in patients with AIDS and malignancies (especially lymphocytic leukemia or Hodgkin’s) and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Usually more severe and often disseminated. Chronic eruptions can be the first sign of HIV infection.

79 Are there any other causes of PV?

A form of PV (but also BP, see question 80) can be drug induced, resulting from penicillamine, captopril, thiol-containing compounds, and rifampin. Emotional stress can also trigger it. Finally, PV may occur in other autoimmune diseases, including myasthenia gravis and thymoma.

82 What is Asboe-Hansen sign?

Another sign of PV; lateral pressure on the edge of a blister may spread it into unaffected skin.

84 What is erythema multiforme (EM)?

A relatively benign process characterized by target or targetoid lesions, with or without blisters, in a symmetric and acral distribution. In fact, the rash favors palms and soles, dorsum of hands, face, and extensor surfaces of extremities (Fig. 3-27). It is often associated with oral lesions, but rarely involves more than one mucosal surface. Although it can be caused by drugs, it is most commonly a sequela of herpes virus infection. It has low morbidity, no mortality, but frequent recurrences. It may be associated with epidermal detachment, yet denudation always involves <10% of BSA.

85 What is Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)?

A potential dermatologic emergency. First described in 1922 by the American pediatricians Albert Stevens and Frank Johnson, SJS is characterized by widespread purpuric macules and targetoid lesions, usually more common on face and torso, and with concomitant mucosal involvement of more than one site (usually the eyes, mouth, and genitalia; Fig. 3-28). Lesions may undergo full-thickness epidermal necrosis, although this is limited by definition to <10% of cutaneous surface. Hence, mortality is much less than in TEN (only 5%).

86 What is toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)?

Also known as Lyell’s syndrome, this is a true dermatologic emergency characterized by widespread skin and mucosal denudation. Skin lesions are erythematous and target-like macules associated with full-thickness epidermal necrosis and detachment of >30% BSA (Fig. 3-29). It is fatal in 50% of the cases, usually because of sepsis and respiratory distress. Mortality is related to BSA involvement: 11% for BSA (which is actually more of a SJS-TEN transitional form), and 35% for BSA >30%.

91 What are the sequelae of SJS/TEN?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree