Chapter 14

The skin

The skin

The first part of this chapter explores the structure and functions of the skin, which is also known as the integumentary system. The effects of ageing on the skin are discussed in the following section. The chapter concludes with a review of common skin conditions.

The skin completely covers the body and is continuous with the membranes lining the body orifices. It:

Structure of the skin

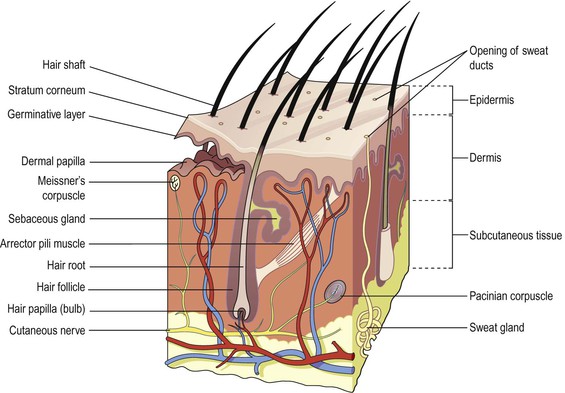

The skin is the largest organ in the body and has a surface area of about 1.5–2 m2 in adults. In certain areas, it contains accessory structures: glands, hair and nails. There are two main layers; the epidermis, which covers the dermis. Between the skin and underlying structures is a subcutaneous layer composed of areolar tissue and adipose (fat) tissue.

Epidermis

This is the most superficial layer and is composed of stratified keratinised squamous epithelium (see Fig. 3.13, p. 39). It varies in thickness, being thickest on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. There are no blood vessels or nerve endings in the epidermis, but its deeper layers are bathed in interstitial fluid from the dermis, which provides oxygen and nutrients, and drains away as lymph.

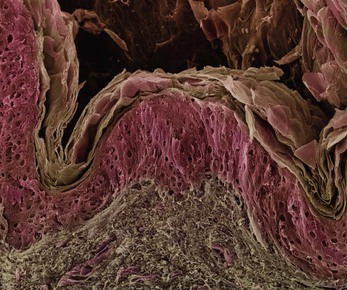

There are several layers (strata) of cells in the epidermis which extend from the deepest germinative layer to the most superficial stratum corneum (a thick horny layer) (Fig. 14.1). Epidermal cells originate in the germinative layer and undergo gradual change as they progress towards the skin surface. The cells on the surface are flat, thin, non-nucleated, dead cells, or squames, in which the cytoplasm has been replaced by the fibrous protein keratin. The surface cells are constantly rubbed off and replaced by those beneath. Complete replacement of the epidermis takes about a month.

Figure 14.1 Coloured scanning electron micrograph of the skin showing the superficial stratum corneum (pale brown), above the lower layers of the epidermis (pink) and the dermis (grey brown).

Healthy epidermis depends upon three processes being synchronised:

• desquamation (shedding) of the keratinised cells from the surface

• effective keratinisation of cells approaching the surface

Hairs, secretions from sebaceous glands and ducts of sweat glands pass through the epidermis to reach the surface.

Upward projections of the dermal layer, the dermal papillae (Fig. 14.2), anchor this securely to the more superficial epidermis and allow passage and exchange of nutrients and wastes to the lower part of the epidermis. This arrangement stabilises the two layers preventing damage due to shearing forces. Blisters develop when trauma causes separation of the dermis and epidermis, and serous fluid collects between the two layers.

In areas where the skin is subject to greater wear and tear, e.g. the palms and fingers of the hands and soles of the feet, the epidermis is thicker and hairs are absent. In these areas the dermal papillae are arranged in parallel lines giving the skin surface a ridged appearance. The pattern of ridges on the fingertips is unique to every individual and the impression made by them is the ‘fingerprint’.

Skin colour is affected by various factors.

• Melanin, a dark pigment derived from the amino acid tyrosine and secreted by melanocytes in the deep germinative layer, is absorbed by surrounding epithelial cells. The amount is genetically determined and varies between different parts of the body, between people of the same ethnic origin and between ethnic groups. The number of melanocytes is fairly constant so the differences in colour depend on the amount of melanin secreted. It protects the skin from the harmful effects of ultraviolet rays in sunlight. Exposure to sunlight promotes synthesis of melanin.

• Normal saturation of haemoglobin (p. 66) and the amount of blood circulating in the dermis give white skin its pink colour. When oxygen saturation is very low, the skin may appear bluish (cyanosis).

Dermis (Fig. 14.2)

The dermis is tough and elastic. It is formed from connective tissue and the matrix contains collagen fibres (see Fig. 3.16, p. 40) interlaced with elastic fibres. Rupture of elastic fibres occurs when the skin is overstretched, resulting in permanent striae, or stretch marks, that may be found in pregnancy and obesity. Collagen fibres bind water and give the skin its tensile strength, but as this ability declines with age, wrinkles develop. Fibroblasts (see Fig. 3.5, p. 34), macrophages (Fig. 3.17, p. 40) and mast cells are the main cells found in the dermis. Underlying its deepest layer is the subcutaneous layer containing areolar tissue and varying amounts of adipose (fat) tissue. The structures in the dermis are:

Blood and lymph vessels.

Arterioles form a fine network with capillary branches supplying sweat glands, sebaceous glands, hair follicles and the dermis. Lymph vessels form a network throughout the dermis.

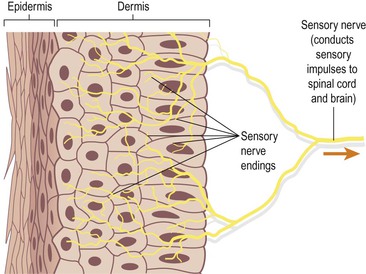

Sensory nerve endings.

Sensory receptors (specialised nerve endings) sensitive to touch, temperature, pressure and pain are widely distributed in the dermis. Incoming stimuli activate different types of sensory receptors (Fig. 14.2, Box 14.1); for example, the Pacinian corpuscle is sensitive to deep pressure (Fig. 14.3). The skin is an important sensory organ through which individuals receive information about their environment. Nerve impulses, generated in the sensory receptors in the dermis, are transmitted to the spinal cord by sensory nerves (Fig. 14.4). From there impulses are conducted to the sensory area of the cerebrum where the sensations are perceived (see Fig. 7.22B, p. 158).

Sweat glands

These are widely distributed throughout the skin and are most numerous in the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, axillae and groins. They are formed from epithelial cells. The bodies of the glands lie coiled in the subcutaneous tissue. There are two types of sweat gland. Eccrine sweat glands are the more common type and open onto the skin surface through tiny pores, and the sweat produced here is a clear, watery fluid important in regulating body temperature. Apocrine glands open into hair follicles and become active at puberty. They may play a role in sexual arousal. These glands are found, for example, in the axilla. Bacterial decomposition of their secretions causes an unpleasant odour. A specialised example of this type of gland is the ceruminous gland of the outer ear, which secretes earwax (Ch. 8).

The most important function of sweat is in the regulation of body temperature (p. 367). Excessive sweating may lead to dehydration and serious depletion of sodium chloride unless intake of water and salt is appropriately increased. After 7–10 days’ exposure to high environmental temperatures the amount of salt lost is substantially reduced but water loss remains high.

Hairs

These grow from hair follicles, downgrowths of epidermal cells into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. At the base of the follicle is a cluster of cells called the hair papilla or bulb. The hair is formed by multiplication of cells of the bulb and as they are pushed upwards, away from their source of nutrition, the cells die and become keratinised. The part of the hair above the skin is the shaft and the remainder, the root (Fig. 14.2). Figure 14.5 shows hair growing through the skin and also desquamation, which roughens the skin surface; the roughened surface may harbour microbial growth although many are removed by the constant rubbing off of the topmost layers.

Hair colour is genetically determined and depends on the amount and type of melanin present. White hair is the result of the replacement of melanin by tiny air bubbles.

Arrector pili (Fig. 14.2).

These are little bundles of smooth muscle fibres attached to the hair follicles. Contraction makes the hair stand erect and raises the skin around the hair, causing ‘goose flesh’. The muscles are stimulated by sympathetic nerve fibres in response to fear and cold. Erect hairs trap air, which acts as an insulating layer. This is an efficient warming mechanism, especially when accompanied by shivering, i.e. involuntary contraction of skeletal muscles.

These consist of secretory epithelial cells derived from the same tissue as the hair follicles. They secrete an oily antimicrobial substance, sebum, into the hair follicles and are present in the skin of all parts of the body except the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. They are most numerous in the scalp, face, axillae and groins. In regions of transition from one type of superficial epithelium to another, such as lips, eyelids, nipple, labia minora and glans penis, there are sebaceous glands that are independent of hair follicles, secreting sebum directly onto the surface.

Sebum keeps the hair soft and pliable and gives it a shiny appearance. On the skin it provides some waterproofing and acts as a bactericidal and fungicidal agent, preventing infection. It also prevents drying and cracking of skin, especially on exposure to heat and sunlight. The activity of these glands increases at puberty and is less at the extremes of age, rendering the skin of infants and older adults prone to the effects of excessive moisture (maceration).

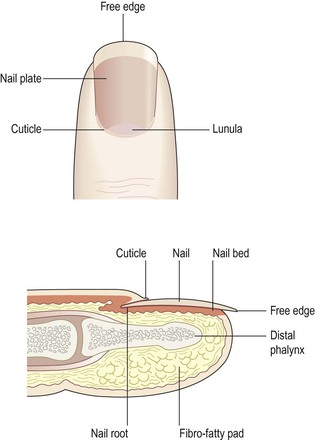

Nails (Fig. 14.6)

Human nails are equivalent to the claws, horns and hooves of animals. Derived from the same cells as epidermis and hair these are hard, horny keratin plates that protect the tips of the fingers and toes.

The root of the nail is embedded in the skin and covered by the cuticle, which forms the hemispherical pale area called the lunula.

The nail plate is the exposed part that has grown out from the nail bed, the germinative zone of the epidermis.

Finger nails grow more quickly than toe nails and growth is faster when the environmental temperature is high.

Functions of the skin