CPRD

THIN

IPCI

BIFAP

HSD

Arianna

Pedianet

Country/region

UK

UK

The Netherlands

Spain

Italy

Italy

Italy

Population

General population, including adults and children

Pediatric and adult population

Pediatric population

Disease codes used

ICD-10 CM and READ codes

READ codes

ICPC codes

ICD-10 codes

ICD-9 CM codes

ICD-9 CM codes

ICD-9 CM codes

Drug codes used

BNF/Multilex codes

BNF/Multilex codes

ATC codes

ATC codes

ATC codes

ATC codes

ATC codes

Electronic medical records from general practitioners are a relatively recent development, mainly due to the increasing computerization of health records in general practice, which is gradually replacing paper medical charts. These databases have several advantages, the most apparent of which is their large size: populations sampled from those databases can be in the order of millions, as with CPRD and THIN. This advantage is of particular importance in drug safety studies where the incidence of adverse drug effects or drug use (or both) can be very low. Patient data (e.g., on diagnosis, drug prescription, etc.) are generally recorded through structured and coded information. Nevertheless, the additional availability of unstructured free-text clinical notes, as in the Dutch GP database “IPCI,” holds potential for manually validating and better characterizing clinical outcomes.

5.2.2 Administrative/Claims Databases

Data in claims/administrative databases are recorded when a patient uses healthcare resources that are provided free of charge to citizens as they are reimbursed by National Health Service (NHS) or when a commercial (e.g., Kaiser Permanente in various North American states) or national social insurance provider (e.g., Medicare in the USA) must be billed for the resources provided. The use and availability of these databases depend on the healthcare system used in each country. The availability of commercial insurance databases is more prominent in countries where healthcare is not provided publicly free of charge and persons must be insured/registered with a health plan to access healthcare resources. Administrative databases generally include pharmacy dispensing and hospital discharge diagnoses which can be linked through patient unique identifier to several other administrative databases (e.g., emergency department visits, outpatient diagnostic test, etc.). Pharmacy claims contain data collected when a patient is dispensed a drug from a pharmacy and its cost is covered by insurance/NHS. The advantage of this data source as opposed to prescription data from a GP database is that, while the latter records only the prescription of a drug, the former can at least ensure that prescribed drug has been dispensed. Neither of the database types can however ensure that a drug is ultimately taken, thus potentially leading to exposure misclassification in case of drug therapies with low adherence. Likewise pharmacy databases, hospital discharge diagnosis databases are built for claims/administrative purposes: healthcare resources related to the management of hospitalized medical event and eventually medical procedures undergone during hospital admission are recorded in order to allow reimbursement by the insurance provider or National Healthcare Service. However, because the billing depends on the type of information that is registered as primary and secondary causes of hospital admission as well as hospital procedures, it is possible that diagnoses in administrative and claims data are recorded less accurately/rigorously than for medical record databases not used for billing purposes. An example of a hospital claims/administrative database is the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), which contains administrative data for over six million patients from 44 children’s hospitals in the USA.

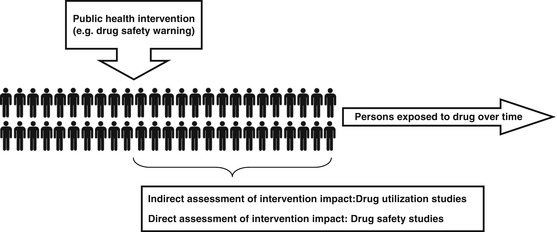

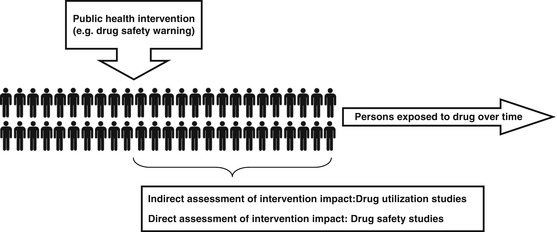

5.3 Observational Studies Concerning Psychotropic Drugs Using Healthcare Databases

Observational drug-related studies in psychiatry conducted using healthcare databases can be divided into two major types: drug utilization (e.g., exploring changes in prevalence and incidence of drug use over time and across different settings, adherence or persistence to drug use and drug switching patterns, etc.) and drug safety studies (risk of adverse outcomes associated with the use of a specific drug). Drug utilization studies are descriptive studies that can be conducted by analyzing an exposure of interest in the underlying general population or selected cohort of patients identified from a database. In the context of pharmacovigilance activities using healthcare databases, it is possible to evaluate the implementation and impact of public health interventions such as drug safety warnings issued by drug agencies and other risk minimization measures (RMMs) rapidly and cost-effectively. This kind of investigation is aimed at exploring any change, if at all, in the drug prescribing pattern occurred as a result of a drug-related public health intervention (i.e., implementation of RMMs) and measuring if the risk of an adverse outcome associated to specific drug treatment was actually minimized after the implementation of the RMM in routine care (Fig. 5.1). This assessment is essential to ensure that the RMMs led to the achievement of expected results in terms of drug-related risk prevention/dilution.

Fig. 5.1

The role of healthcare databases in the assessment of public health interventions

Drug safety studies can be conducted using analytical methods that can estimate the risk of an outcome following exposure to a drug. Nowadays, the assessment of specific associations of drugs and adverse events is mostly carried out using well-established study designs such as propensity score-matched new user cohorts or case-control designs, nested in a cohort of new users of the drugs under study. More recently, advance statistical techniques have been applied to data from healthcare databases also for post-marketing assessment and comparison of benefits of psychotropic drugs in the context of comparative effectiveness research.

5.3.1 Drug Utilization Studies

Healthcare databases have been widely used to analyze the prescribing pattern of psychotropic drugs in clinical practice, mainly antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines. Drug utilization studies have been carried out in the general population as well as in “special” subsets of population such as elderly or pediatric patients and pregnant women. Data on the prevalence/incidence of drug treatment, adherence, and persistence to drug therapy provides an indication of quality of care.

An example of how the drug prevalence proves useful can be seen in antidepressant utilization studies, which are commonly carried out at regional (Poluzzi et al. 2013; Parabiaghi et al. 2011), national (Sultana et al. 2014b; Chollet et al. 2013; Lam et al. 2013), or multinational (Abbing-Karahagopian et al. 2014) level. Such studies can give an indication of appropriate drug prescribing by confirming whether first-line agents are indeed most commonly used and if the drugs are used in agreement with international treatment guidelines and Summary of Products Characteristics. If the electronic data source also has the indication of use included in the prescription data, researchers can further investigate whether drug prescribing is prescribed appropriately or off-label. Another example of the usefulness of prevalence and incidence data concerns the assessment of the distribution of prescription of generic or branded drugs for drugs that are off- patent. Several clinical guidelines suggest that generic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in particular, should be prescribed as first-line agents to reduce the use of healthcare resources and promote sustainability of national healthcare systems. An example of a basic evaluation of prescribing appropriateness would be to compare the prevalence of generic and brand antidepressant drug use using pharmacy data (Ubeda et al. 2007). Such investigations have been put to use by national drug observatories to find out the extent of generic antidepressant penetration. A more complex investigation of generic antidepressant drug use might involve a comparison of selected outcomes that reflect drug safety such as mortality and other health resource consumption (hospitalizations, specialist examinations, other drugs) between generic and brand antidepressant users (Colombo et al. 2013).

Information on adherence/persistence complements prevalence data. A detailed analysis of antidepressant use consistently shows that adherence levels are usually low (Hansen et al. 2004). In fact, most of the drug utilization database studies on antidepressants found that these drugs are frequently withdrawn as early as 3 months after the therapy starts in a large proportion of depressed patients even though guidelines suggest at least 1 year treatment (Poluzzi et al. 2013; Parabiaghi et al. 2011; Sultana et al. 2014b; Chollet et al. 2013). Analysis of persistence to drug treatment can be useful as it may indirectly imply tolerability or lack of efficacy: in the absence of economic reasons, a drug which is switched more often than others may be less effective and/or less tolerable than other drugs. For example, a US-based study using claims data found that patients prescribed with escitalopram were more likely to persist with their antidepressant treatment and less likely to switch to other antidepressants, compared to other SSRI users (Esposito et al. 2009).

Another class of drugs that has been the subject of many drug utilization studies is that of antipsychotics. This is particularly important given the diverse pharmacological and safety profile of antipsychotic drugs as well as their several indications of use apart from schizophrenia and mania, which currently include motor tics, nausea, and vomiting in palliative care and intractable hiccups for haloperidol and persistent aggression in pediatric conduct disorders and persistent aggression in Alzheimer’s disease for risperidone. Drug utilization studies highlighted the increasing use of second-generation or atypical antipsychotics in the general population, particularly in elderly persons (Trifirò et al. 2005, 2010a). Studies investigating antipsychotic adherence were also pivotal, suggesting that nonadherence is a significant problem in schizophrenia and is associated with negative outcomes such as hospitalization (Tiihonen et al. 2006; Ascher-Svanum et al. 2006; Gilmer et al. 2004). Some examples of psychotropic drug utilization database studies are reported in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2

Examples of psychotropic drug utilization studies carried out using healthcare databases

Author (year) | Setting | Population | Exposure | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Marston et al. (2014) | THIN database | General population | APs | APs prescribing rate in primary care |

Petersen et al. (2014) | THIN database | Pregnant women | APs | Discontinuation of APs in pregnancy |

Wijlaars et al. (2012) | THIN database | Children and adolescents | ADs | Trends in depression and antidepressant prescribing in children and adolescents |

Man et al. (2012) | THIN database | Pregnant women | AED | Prevalence of AED use in pregnancy |

Hayes et al. (2011) | THIN database | General population | Psychotropic drugs used in bipolar disorder | Prescribing trends of drugs used in bipolar disorder |

Prah et al. (2011) | THIN database | General population | APs | Prescribing trends of APs for schizophrenia |

Petersen et al. (2011) | THIN database | Pregnant women | ADs | AD discontinuation |

Aguglia et al. (2012) | HSD | General population | SSRI and SNRI | SSRI/SNRI prescribing pattern |

Parabiaghi et al. (2011) | HSD | Elderly population | ADs | AD utilization among elderly in Lombardy |

Trifirò et al. (2010a) | HSD | Elderly persons with dementia | APs | AP prescribing pattern |

Savica et al. (2007) | HSD | General population | AEDs | AED prescribing pattern |

Trifirò et al. (2005) | HSD | General population | AP | AP prescribing pattern |

Koopman et al. (2010) | IPCI | General population | Drugs used to treat neuropathic pain | Pharmacological treatment of neuropathic facial pain |

Kraut et al. (2013) | GePaRD | Pediatric population | Methylphenidate | Comorbidities in ADHD children treated with methylphenidate |

Lindemann et al. (2012) | GePaRD | Children and adolescents | ADHD drugs | Age-specific prevalence, incidence of new diagnoses, and drug treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

Jacobsen et al. (2014) | Aarhus University Prescription Database | Pediatric population | AEDs | Prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs |

Laugesen et al. (2013) | Aarhus University Prescription Database | Female general population | SSRIs | Use of SSRIs and lifestyle among women of childbearing age |

Hsia et al. (2010) | PEDIANET, IPCI, and IMS disease analyzer | Pediatric population | AEDs | AED prescribing among children |

5.3.2 Evaluation the Impact of Drug-Related Risk Minimization Measures in Psychiatry

Understanding prescriber behavior is important particularly from a public health perspective. Knowledge of drug safety is constantly expanding and clinical guidelines are continuously evolving in response to this. Sometimes rapid changes in prescriber behavior are critical, as when prescribers are expected to respond promptly to drug safety warnings. For example, studies of prescriber behavior are necessary to see whether citalopram-related drug safety warnings on the risk of cardiac arrhythmia resulted in a change of citalopram prescribing among persons at higher risk of such adverse effects. Similarly, healthcare databases have also been used to investigate changes in prescribing pattern after the antipsychotic-related safety warnings in older people with dementia. In short, Health Canada, the European Medicines Agency, the Food and Drug Administration, and other national drug agencies issued several warnings from 2002 onward on the risk of adverse events such as all-cause mortality and stroke when antipsychotics are used mostly off-label in elderly persons with dementia, highlighting their unfavorable risk-benefit ratio. A summary of studies investigating changes in antipsychotic prescribing pattern among elderly dementia patients is shown in Table 5.3. Such investigations can be said to be indirect evaluations of drug-related public health interventions, because the primary aim of such interventions is not the reduction of drug prescribing per se but a reduction in the drug-related risk as a consequence of a more cautious use of the drug (Fig. 5.1). Healthcare databases can also be used to carry out a direct evaluation of a safety warning impact by measuring the occurrence of a known adverse drug reaction before and after a warning.

Table 5.3

Overview of database studies evaluating the impact of antipsychotic drug safety warnings on the pattern of use of these drugs in routine care

Author (year) | Setting | Population | Exposure | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Gallini et al. (2014) | EGB database (France) | Elderly patients with and without dementia | All APs, APs by class and olanzapine and risperidone individually | Monthly prevalence of AP use |

Schulze et al. (2013) | GEK database (Germany) | Elderly dementia patients | All APs and APs by class | Yearly prevalence of AP use, number of AP packages, and DDD per person per year |

Guthrie et al. (2013) | PCCIU database (Scotland) | Elderly dementia patients | All APs and risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine individually | Quarterly prevalence of oral AP prescribing, initiation, and discontinuation; prescription of hypnotics, anxiolytics, or antidepressants |

Franchi et al. (2012) | Lombardy Region Drug Administrative Database (Italy) | Elderly dementia patients treated with AChEIs | All APs, APs by class and olanzapine, quetiapine, haloperidol, clotiapine, and risperidone individually | Number of AP prescriptions per person and gap between AP prescriptions; yearly prevalence of AP use, probability of continuing antipsychotic treatment |

Dorsey et al. (2010) | IMS Health’s National Disease and Therapeutic Index (USA) | Elderly dementia patients | All APs and APs by class | Monthly prevalence of AP use, monthly change in AP drug use, and annual growth rate of AP use |

Sanfélix-Gimeno et al. (2009) | Valencia Health Agency pharmacy claims database (Spain) | Elderly patients and younger adults | Risperidone and olanzapine use (stratified by strength) | Monthly prevalence of AP use |

Valiyeva et al. (2008) | Ontario Drug Benefit database (Canada) | Elderly dementia patients | All APs, APs by class and olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone individually | Monthly prevalence of AP use; change in the number of patients prescribed an AP and ratio of change of prescription rate after the safety warnings |

More recently, healthcare databases have been increasingly used to carry out postauthorization safety studies (PASS) also concerning psychotropic drugs. A PASS is a scientific investigation of the safety profile of a drug that has already been marketed with the aim of identifying and describing the safety profile of that drug, as indicated in the risk management plan (RMP) supporting the premarketing documentation. In this case, healthcare databases can be used to estimate the frequency of known ADRs within a given exposed population or to identify predictors of drug-related risks, thus identifying categories of patients at high risk of developing ADRs; on the other hand, it is unlikely for healthcare databases to have a major role in de novo signal detection (hypothesis generation) in the immediate future, despite the several international initiatives that have been carried out to better explore this issue in the last years (Trifirò et al. 2014a). A PASS can also be carried out with the aim of measuring whether any risk minimization measures implemented as part of a RMP were effective or otherwise. Among other things, RMPs also cover planning for how drug-related risks can be prevented or minimized as well as plans for studies aimed at increasing awareness on drug safety; healthcare databases have a pivotal role in both these aspects.

5.3.3 Drug Safety Studies

The safety profile of therapeutic drugs including psychotropic drugs is initially investigated in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in the premarketing phase. However, drug safety data from RCTs is fraught with limitations such as small and highly selective study populations as well as limited duration of the observation period which preclude the possibility of identifying potentially severe adverse drug reactions with long-term onset or which are more likely to occur when used in patients affected by several comorbidities or receiving concomitant medications at interaction risk (Sultana et al. 2013). In fact RCT populations may be healthier than patients in real clinical practice and less likely to be prescribed a multidrug regimen as RCTs in the drug development phase tend to exclude the frailest patient categories such as very old patients who are generally affected by multiple comorbidities. Since the number of patients enrolled in a RCT is small compared to the number of patients that will be exposed to a drug in clinical practice, RCTs are unlikely to detect even life-threatening ADRs which occur rarely. These limitations can be addressed by observational studies, including those making use of databases, since such studies typically include data from long follow-up of large populations that are representative of real clinical settings, i.e., patients of all ages (pediatric and/or geriatric populations) and those at higher risk of an adverse drug reaction (the oldest old, patients with several comorbidities, and those with on a multidrug regimen).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree