Table 5.1)

Cough and sputum

Cough is a common presenting respiratory symptom. It occurs when deep inspiration is followed by explosive expiration. Flow rates of air in the trachea approach the speed of sound during a forceful cough. Coughing enables the airways to be cleared of secretions and foreign bodies. The duration of a cough is important.

| Major symptoms |

| Cough |

| Sputum |

| Haemoptysis |

| Dyspnoea (acute, progressive or paroxysmal) |

| Wheeze |

| Chest pain |

| Fever |

| Hoarseness |

| Night sweats |

Find out when the cough first became a problem. A cough of recent origin, particularly if associated with fever and other symptoms of respiratory tract infection, may be due to acute bronchitis or pneumonia. A chronic cough (of more than 8 weeks duration) associated with wheezing may be due to asthma; sometimes asthma can present with just cough alone. A change in the character of a chronic cough may indicate the development of a new and serious underlying problem (e.g. infection or lung cancer).

A differential diagnosis of cough based on its character is shown in

TABLE 5.2 Differential diagnosis of cough based on its character

| Origin | Character | Causes |

| Naso-pharynx/larynx | Throat clearing, chronic | Postnasal drip, acid reflux |

| Larynx | Barking, painful, acute or persistent | Laryngitis, pertussis (whooping cough), croup |

| Trachea | Acute, painful | Tracheitis |

| Bronchi | Intermittent, sometimes productive, worse at night | Asthma |

| Worse in morning | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | |

| With blood | Bronchial malignancy | |

| Lung parenchyma | Dry then productive | Pneumonia |

| Chronic, very productive | Bronchiectasis | |

| Productive, with blood | Tuberculosis | |

| Irritating and dry, persistent | Interstitial lung disease | |

| Worse on lying down, sometimes with frothy sputum | Pulmonary oedema | |

| ACE inhibitors | Dry, scratchy, persistent | Medication-induced |

TABLE 5.3 Differential diagnosis of cough based on its duration

| Acute cough (<3 weeks duration): differential diagnosis |

| Chronic cough: differential diagnosis and clues |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

PND = paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

A cough associated with a postnasal drip or sinus congestion or headaches may be due to the upper airway cough syndrome, which is the single most common cause of chronic cough. Although patients with this problem often complain of a cough, when asked to demonstrate their cough they do not cough but clear the throat. An irritating, chronic dry cough can result from oesophageal reflux and acid irritation of the lungs. There is some controversy about these as causes of true cough. A similar dry cough may be a feature of late interstitial lung disease or associated with the use of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors—drugs used in the treatment of hypertension and cardiac failure. Cough that wakes a patient from sleep may be a symptom of cardiac failure or of the reflux of acid from the oesophagus into the lungs that can occur when a person lies down. A chronic cough that is productive of large volumes of purulent sputum may be due to bronchiectasis.

Patients’ descriptions of their cough may be helpful. In children, a cough associated with inflammation of the epiglottis may have a muffled quality and cough related to viral croup is often described as ‘barking’. Cough caused by tracheal compression by a tumour may be loud and brassy. Cough associated with recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy has a hollow sound because the vocal cords are unable to close completely; this has been described as a bovine cough. A cough that is worse at night is suggestive of asthma or heart failure, while coughing that comes on immediately after eating or drinking may be due to incoordinate swallowing or oesophageal reflux or, rarely, a tracheo-oesophageal fistula.

It is an important (though perhaps a somewhat unpleasant task) to inquire about the type of sputum produced and then to look at it, if it is available. Be warned that some patients have more interest in their sputum than others and may go into more detail than you really want. A large volume of purulent (yellow or green) sputum suggests the diagnosis of bronchiectasis or lobar pneumonia. Foul-smelling dark-coloured sputum may indicate the presence of a lung abscess with anaerobic organisms. Pink frothy secretions from the trachea, which occur in pulmonary oedema, should not be confused with sputum. It is best to rely on the patient’s assessment of the taste of the sputum, which, not unexpectedly, is foul in conditions like bronchiectasis or lung abscess.

Haemoptysis

Haemoptysis (coughing up of blood) can be a sinister sign of lung disease (

TABLE 5.4 Causes (differential diagnosis) of haemoptysis and typical histories

| Respiratory | |

| Bronchitis | Small amounts of blood with sputum |

| Bronchial carcinoma | Frank blood, history of smoking, hoarseness |

| Bronchiectasis | Large amounts of sputum with blood |

| Pneumonia | Fever, recent onset of symptoms, dyspnoea |

| (The above four account for about 80% of cases) | |

| Pulmonary infarction | Pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea |

| Cystic fibrosis | Recurrent infections |

| Lung abscess | Fever, purulent sputum |

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Previous TB, contact with TB, HIV-positive status |

| Foreign body | History of inhalation, cough, stridor |

| Goodpasture’s | Pulmonary haemorrhage, glomerulonephritis, antibody to basement membrane antigens |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | History of sinusitis, saddle-nose deformity |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pulmonary haemorrhage, multi-system involvement |

| Rupture of a mucosal blood vessel after vigorous coughing | |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Mitral stenosis (severe) | |

| Acute left ventricular failure | |

| Bleeding diatheses | |

Note: Exclude spurious causes, such as nasal bleeding or haematemesis.

* Ernest W Goodpasture (1886–1960), pathologist at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. He described this syndrome in 1919.

TABLE 5.5 Features distinguishing haemoptysis from haematemesis and nasopharyngeal bleeding

| Favours haemoptysis | Favours haematemesis | Favours nasopharyngeal bleeding |

| Mixed with sputum | Follows nausea | Blood appears in mouth |

| Occurs immediately after coughing | Mixed with vomitus; follows dry retching |

Ask how much blood has been produced. Mild haemoptysis usually means less than 20 mL in 24 hours. It appears as streaks of blood discolouring sputum. Massive haemoptysis is more than 250 mL of blood in 24 hours and represents a medical emergency. Its most common causes are carcinoma, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis and tuberculosis.

Breathlessness (dyspnoea) (

The awareness that an abnormal amount of effort is required for breathing is called dyspnoea. It can be due to respiratory or cardiac disease, or lack of physical fitness. Careful questioning about the timing of onset, severity and pattern of dyspnoea is helpful in making the diagnosis (

Questions box 5.2

Questions to ask the breathless patient

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

TABLE 5.7 Differential diagnosis of dyspnoea based on time course of onset

| Seconds to minutes—favours: |

| Hours or days—favours: |

| Weeks or longer—favours: |

Questions to ask the patient with a cough

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

only on heavy exertion or have much more limited exercise tolerance. Dyspnoea can be graded from I to IV based on the New York Heart Association classification:

It is more useful, however, to determine the amount of exertion that actually causes dyspnoea—that is, the distance walked or the number of steps climbed.

The association of dyspnoea with wheeze suggests airways disease, which may be due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (

TABLE 5.8 Characteristics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

| History |

| Examination |

TABLE 5.9 Differential diagnosis of dyspnoea of sudden onset based on other features

| Presence of pleuritic chest pain—favours: |

| Absence of chest pain—favours: |

| Presence of central chest pain—favours: |

| Presence of cough and wheeze—favours: |

Wheeze

A number of conditions can cause a continuous whistling noise that comes from the chest (rather than the throat) during breathing. These include asthma or COPD, infections such as bronchiolitis and airways obstruction by a foreign body or tumour. Wheeze is usually maximal during expiration and is accompanied by prolonged expiration. This must be differentiated from stridor (see below), which can have a similar sound, but is loudest over the trachea and occurs during inspiration.

Chest pain

Chest pain due to respiratory disease is usually different from that associated with myocardial ischaemia (

Other presenting symptoms

Bacterial pneumonia is an acute illness in which prodromal symptoms (fever, malaise and myalgia) occur for a short period (hours) before pleuritic pain and dyspnoea begin. Viral pneumonia is often preceded by a longer (days) prodromal illness. Patients may occasionally present with episodes of fever at night. Tuberculosis, pneumonia and lymphoma should always be considered in these cases. Occasionally patients with tuberculosis present with episodes of drenching sweating at night.

Hoarseness or dysphonia (an abnormality of the voice) may sometimes be considered a respiratory system symptom. It can be due to transient inflammation of the vocal cords (laryngitis), vocal cord tumour or recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

Sleep apnoea is an abnormal increase in the periodic cessation of breathing during sleep. Patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) (where airflow stops during sleep for periods of at least 10 seconds and sometimes for over 2 minutes, despite persistent respiratory efforts) typically present with daytime somnolence, chronic fatigue, morning headaches and personality disturbances. Very loud snoring may be reported by anyone within earshot. These patients are often obese and hypertensive. The Epworth sleepiness scale is a way of quantifying the severity of sleep apnoea (

TABLE 5.10 The Epworth sleepiness scale

| ‘How easily would you fall asleep in the following circumstances?’ |

* A normal score is between 0 and 9. Severe sleep apnoea scores from 11 to 20.

Patients with central sleep apnoea (where there is cessation of inspiratory muscle activity) may also present with somnolence but do not snore excessively (

TABLE 5.11 Abnormal patterns of breathing

| Type of breathing | Cause(s) |

| 1 Sleep apnoea—cessation of airflow for more than 10 seconds more than 10 times a night during sleep | Obstructive (e.g. obesity with upper airway narrowing, enlarged tonsils, pharyngeal soft tissue changes in acromegaly or hypothyroidism) |

| 2 Cheyne-Stokes | |

| 3 Kussmaul’s breathing (air hunger)— deep, rapid respiration due to stimulation of the respiratory centre | Metabolic acidosis (e.g. diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure) |

| 4 Hyperventilation, which results in alkalosis and tetany | Anxiety |

| 5 Ataxic (Biot | Brainstem damage |

| 6 Apneustic breathing—a post-inspiratory pause in breathing | Brain (pontine) damage |

| 7 Paradoxical respiration—the abdomen sucks inwards with inspiration (it normally pouches outwards due to diaphragmatic descent) | Diaphragmatic paralysis |

* John Cheyne (1777–1836), Scottish physician who worked in Dublin, described this in 1818. William Stokes (1804–1878), Irish physician, described it in 1854.

† Camille Biot (b. 1878), French physician.

Some patients respond to anxiety by increasing the rate and depth of their breathing. This is called hyperventilation. The result is an increase in CO2 excretion and the development of alkalosis—a rise in the pH of the blood. These patients may complain of variable dyspnoea; they have more difficulty breathing in than out. The alkalosis results in paraesthesiae of the fingers and around the mouth, light-headedness, chest pain and a feeling of impending collapse.

Treatment

It is important to find out what drugs the patient is using (

TABLE 5.12 Drugs and the lungs

| Cough |

| Wheeze |

| Interstitial lung disease (pulmonary fibrosis) |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema |

| Pleural disease/effusion |

Almost every class of drug can produce lung toxicity. Examples include pulmonary embolism from use of the oral contraceptive pill, interstitial lung disease from cytotoxic agents (e.g. methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin), bronchospasm from beta-blockers or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and cough from ACE inhibitors. Some medications known to cause lung disease may not be mentioned by the patient because they are illegal (e.g. cocaine), are used sporadically (e.g. hydrochlorothiazide), can be obtained over the counter (e.g. tryptophan) or are not taken orally (e.g. timolol; beta-blocker eye drops for glaucoma). The clinician therefore needs to ask about these types of drug specifically.

Past history

One should always ask about previous respiratory illness, including pneumonia, tuberculosis or chronic bronchitis, or abnormalities of the chest X-ray that have previously been reported to the patient. Many previous respiratory investigations may have been memorable, such as bronchoscopy, lung biopsy and video-assisted thoracoscopy. Spirometry, with or without challenge testing for asthma, may have been performed. Many severe asthmatics perform their own regular peak flow testing (

Occupational history

In no system are the patient’s present and previous occupations of more importance (

TABLE 5.13 Occupational lung disease (pneumoconioses)

| Substance | Disease |

| Coal | Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis |

| Silica | Silicosis |

| Asbestos | Asbestosis |

| Talc | Talcosis |

One must ask about exposure to dusts in mining industries and factories (e.g. asbestos, coal, silica, iron oxide, tin oxide, cotton, beryllium, titanium oxide, silver, nitrogen dioxide, anhydrides). Heavy exposure to asbestos can lead to asbestosis (

TABLE 5.14 Possible occupational exposure to asbestos

| Asbestos mining, including relatives of miners |

| Naval dockyard workers and sailors—lagging of pipes |

| Builders—asbestos in fibreboard (particles are released during cutting or drilling) |

| Factory workers—manufacture of fibro-sheets, brake linings, some textiles |

| Building maintenance workers—asbestos insulation |

| Building demolition workers |

| Home renovation |

Work or household exposure to animals, including birds, is also relevant (e.g. Q fever or psittacosis which are infectious diseases caught from animals).

Exposure to organic dusts can cause a local immune response to organic antigens and result in allergic alveolitis. Within a few hours of exposure, patients develop flu-like symptoms. These often include fever, headache, muscle pains, dyspnoea without wheeze and dry cough. The culprit antigens may come from mouldy hay, humidifiers or air conditioners, among others (

TABLE 5.15 Allergic alveolitis—sources

| Bird fancier’s lung | Bird feathers and excreta |

| Farmer’s lung | Mouldy hay or straw (Aspergillus fumigatus) |

| Byssinosis | Cotton or hemp dust |

| Cheese worker’s lung | Mouldy cheese (Aspergillus clavatus) |

| Malt worker’s lung | Mouldy malt (Aspergillus clavatus) |

| Humidifier fever | Air-conditioning (thermophilic Actinomycetes) |

It is most important to find out what the patient actually does when at work, the duration of any exposure, use of protective devices and whether other workers have become ill. An improvement in symptoms over the weekend is a valuable clue to the presence of occupational lung disease, particularly occupational asthma. This can occur as a result of exposure to spray paints or plastic or soldering fumes.

Social history

A smoking history must be routine, as it is the major cause of COPD and lung cancer (see

Many respiratory conditions are chronic, and may interfere with the ability to work and exercise and interfere with normal family life. In some cases involving occupational lung disease there may be compensation matters affecting the patient. Ask about these problems and whether the patient has been involved in a pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Housing conditions may be inappropriate for a person with a limited exercise tolerance or an infectious disease. An inquiry about the patient’s alcohol consumption is important. The drinking of large amounts of alcohol in binges can sometimes result in aspiration pneumonia, and alcoholics are more likely to develop pneumococcal or Klebsiella pneumonia. Intravenous drug users are at risk of lung abscess and drug-related pulmonary oedema. Sexual orientation or history of intravenous drug use may be related to an increased risk of HIV infection and susceptibility to infection. Such information may influence the decision about whether to advise treatment at home or in hospital.

Family history

A family history of asthma or other atopic diseases, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer or emphysema should be sought. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, for example, is an inherited disease, and those affected are extremely susceptible to the development of emphysema. A family history of infection with tuberculosis is also important. A number of pulmonary diseases may have a familial or genetic association. These include carcinoma of the lung and pulmonary hypertension.

The respiratory examination

Examination anatomy

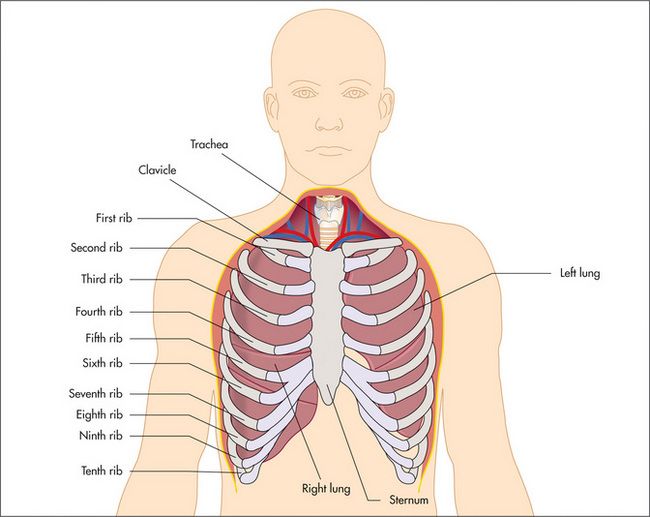

The lungs are paired asymmetrical organs protected by the cylinder composed of the ribs, vertebrae and diaphragm. The surface of the lungs is covered by the visceral pleura, a thin membrane, and a similar outer layer (the parietal pleura) lines the rib cage. These membranes are separated by a thin layer of fluid and enable the lungs to move freely during breathing. Various diseases of the lungs and of the pleura themselves, including infection and malignancy, can cause accumulation of fluid within the pleural cavity (a pleural effusion).

The heart, trachea, oesophagus and the great blood vessels and nerves sit between the lungs and make up the structure called the mediastinum. The left and right pulmonary arteries supply their respective lung. Gas exchange occurs in the pulmonary capillaries which surround the alveoli, the tiny air sacs which lie beyond the terminal bronchioles. Oxygenated blood is returned via the pulmonary veins to the left atrium. Abnormalities of the pulmonary circulation such as raised pulmonary venous pressure resulting from heart failure or pulmonary hypertension can interfere with gas exchange.

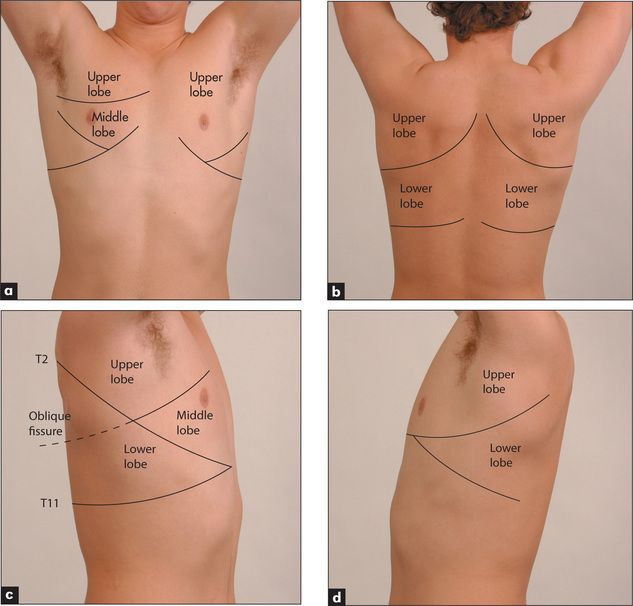

The position of the heart with its apex pointing to the left means that the left lung is smaller than the right and has only two lobes, which are separated by the oblique fissure. The right lung has both horizontal (upper) and oblique (lower) fissures dividing it into three lobes (

(a) Anterior. (b) Posterior. (c) Lobes of the right lung. (d) Lobes of the left lung. Refer to

The muscles of respiration are the diaphragm upon which the bases of the lungs rest and the intercostal muscles. During inspiration the diaphragm flattens and the intercostal muscles contract to elevate the ribs. Intrathoracic pressure falls as air is forced under atmospheric pressure into the lungs. Expiration is a passive process resulting from elastic recoil of the muscles. Abnormalities of lung function or structure may change the normal anatomy and physiology of respiration, for example as a result of over-inflation of the lungs (COPD,

During the respiratory examination, keep in mind the surface anatomy (

Positioning the patient

The patient should be undressed to the waist.

General appearance

If the patient is an inpatient in hospital, look around the bed for oxygen masks, metered dose inhalers (puffers) and other medications, and the presence of a sputum mug. Then make a deliberate point of looking for the following signs before beginning the detailed examination.

Dyspnoea

Watch the patient for signs of dyspnoea at rest. Count the respiratory rate; the normal rate at rest should not exceed 25 breaths per minute (range 16–25). The frequently quoted normal value of 14 breaths per minute is probably too low; normal people can have a respiratory rate of up to 25, and the average is 20 breaths per minute. It is traditional to count the respiratory rate surreptitiously while affecting to count the pulse. The respiratory rate is the only vital sign that is under direct voluntary control. Tachypnoea refers to a rapid respiratory rate of greater than 25. Bradypnoea is defined as a rate below 8, a level associated with sedation and adverse prognosis. In normal relaxed breathing, the diaphragm is the only active muscle and is active only in inspiration; expiration is a passive process.

Characteristic signs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Look to see whether the accessory muscles of respiration are being used. This is a sign of an increase in the work of breathing, and COPD is an important cause. These muscles include the sternomastoids, the platysma and the strap muscles of the neck. Characteristically the accessory muscles cause elevation of the shoulders with inspiration, and aid respiration by increasing chest expansion. Contraction of the abdominal muscles may occur in expiration in patients with obstructed airways. Patients with severe COPD often have indrawing of the intercostal and supraclavicular spaces during inspiration. This is due to a delayed increase in lung volume despite the generation of large negative pleural pressures.

In some cases, the pattern of breathing is diagnostically helpful (

Cyanosis

Central cyanosis is best detected by inspecting the tongue. Examination of the tongue differentiates central from peripheral cyanosis. Lung disease severe enough to result in significant ventilation–perfusion imbalance, such as pneumonia, COPD and pulmonary embolism, may cause reduced arterial oxygen saturation and central cyanosis. Cyanosis becomes evident when the absolute concentration of deoxygenated haemoglobin is 50 g/L of capillary blood. Cyanosis is usually obvious when the arterial oxygen saturation falls below 90% in a person with a normal haemoglobin level. Central cyanosis is therefore a sign of severe hypoxaemia. In patients with anaemia, cyanosis does not occur until even greater levels of arterial desaturation are reached. The absence of obvious cyanosis does not exclude hypoxia. The detection of cyanosis is much easier in good (especially fluorescent) lighting conditions and is said to be more difficult if the patient’s bed is surrounded by cheerful pink curtains.

Character of the cough

Coughing is a protective response to irritation of sensory receptors in the submucosa of the upper airways or bronchi. Ask the patient to cough several times. Lack of the usual explosive beginning may indicate vocal cord paralysis (the ‘bovine’ cough). A muffled, wheezy, ineffective cough suggests obstructive pulmonary disease. A very loose productive cough suggests excessive bronchial secretions due to chronic bronchitis, pneumonia or bronchiectasis. A dry, irritating cough may occur with chest infection, asthma or carcinoma of the bronchus and sometimes with left ventricular failure or interstitial lung disease. It is also typical of the cough produced by ACE inhibitor drugs. A barking or croupy cough may suggest a problem with the upper airway—the pharynx and larynx, or pertussis infection.

Sputum

Sputum should be inspected. Careful study of the sputum is an essential part of the physical examination. The colour, volume and type (purulent, mucoid or mucopurulent), and the presence or absence of blood, should be recorded.

Stridor

Obstruction of the larynx or trachea (the extra-thoracic airways) may cause stridor, a rasping or croaking noise loudest on inspiration. This can be due to a foreign body, a tumour, infection (e.g. epiglottitis) or inflammation (

TABLE 5.16 Some causes of stridor in adults

| Sudden onset (minutes) |

| Gradual onset (days, weeks) |

Hoarseness

Listen to the voice for hoarseness (dysphonia), as this may indicate recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy associated with carcinoma of the lung (usually left-sided), or laryngeal carcinoma. However, the commonest cause is laryngitis and the use of inhaled corticosteroids for asthma. Non-respiratory causes include hypothyroidism.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree