Anatomy and Physiology

The pituitary regulates key physiologic processes including growth, metabolism, reproduction, and homeostasis. The pituitary gland extends by a narrow stalk from the hypothalamus into the sella turcica within the sphenoid bone (

26,

27,

28). The pituitary gland is a small ovoid structure that is divided into a red-brown anterior lobe (adenohypophysis), a gray-white posterior lobe (neurohypophysis), and an indistinct intermediate lobe. The pituitary gland weighs approximately 100 mg at birth and increases in weight

during adolescence to its adult weight of 500 to 600 mg. The adenohypophysis accounts for 80% of the gland (

26,

27). The neonatal pituitary gland is especially prominent, owing to its stimulation by maternal hormones, but it undergoes some involution in the postnatal period, followed by increased growth through the age of 3 years. A notable increase in the size of the gland occurs with menarche and pregnancy. Generally, the pituitary gland in women after puberty weighs more than the gland in men. Suprasellar extension of the pituitary gland during puberty has been reported as a normal variant.

The pituitary gland receives its vascular supply from two hypophyseal arteries that branch from the internal carotid arteries and give rise to two anastomosing networks of capillaries that surround the stalk and adenohypophysis. The hypophyseal portal circulation, which arises from the second capillary plexus, supplies the adenohypophysis (

26,

27). A thin diaphragm, arising from the dura, covers the opening to the sella turcica, but in the center of the diaphragm, the pituitary stalk passes through an aperture. The pituitary gland is not covered by meninges. The periosteal dura lines the sella turcica.

The adenohypophysis is composed of three cell types on histologic examination: the chromophobes, acidophils, and basophils, accounting for 50%, 40%, and 10% of adenohypophyseal cells, respectively (eFigure 21-15). Five main hormonally active cell types are identifiable in the adult gland, which express six different hormones. The cell types and their respective hormones are the somatotrophs (growth hormone), lactotrophs (prolactin), corticotrophs (ACTH), gonadotrophs (FSH/LH), and thyrotrophs (TSH), accounting for 40% to 50%, 10% to 30%, 10% to 20%, 5% to 10%, and 5% of the adenohypophyseal cells, respectively (

27,

28). Stimulating and inhibitory hypothalamic factors released into the hypophy-seal-portal circulation regulate the release of these hormones from the adenohypophysis (eFigure 21-16).

The folliculostellate cells are agranular; immunostain for S100, GFAP, and vimentin (VIM); and extend between the other adenohypophyseal cells. These cells are thought to have a paracrine regulatory function on the hormone-producing cells (

27). Calcified concretions are an incidental finding in the anterior pituitary of ostensibly normal fetuses and neonates.

The posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) contains the axonal processes of neurosecretory neurons that originate in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus to secrete vasopressin and oxytocin, respectively. Vasopressin and oxytocin are stored in secretory granules (Herring bodies) in the nerve endings (

27). The intermediate lobe contains melanotrophs. These produce proopiomelanocortin (POMC), a precursor for endorphins as well as melanocyte-stimulating factor (MSH).

The development of the pituitary is complex and depends on a series of signals that are expressed in distinct spatial and temporal patterns. Defects in these signals can lead to developmental defects as outlined below. The anterior and intermediate lobes develop from oral ectoderm, while the posterior lobe arises from neuroectoderm through an evagination of tissue from the base of the developing diencephalon. During the 4th week of gestation, an outpouching of ectoderm from the roof of the stomatodeum (primitive oral cavity) grows dorsally toward the diencephalon as Rathke pouch. Along this route of migration, progenitor cells of the future adenohypophysis may lag behind as potential sources of ectopic anterior pituitary. Constriction and disappearance of Rathke pouch during the 5th to 6th gestational week separate the adenohypophysis from the stomatodeum. Concurrently, the elongating Rathke pouch passes between the developing presphenoid and basisphenoid bones of the skull and joins with the infundibulum, a diverticulum arising from the diencephalon, as the future neurohypophysis. The first vestiges of the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal circulation are seen at 7 weeks’ gestation, with the process being complete at 18 to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Somatotrophs and corticotrophs are identified immunohistochemically in the adenohypophysis between the 5th and 12th gestational week. By 12 to 13 weeks’ gestation, thyrotrophs and gonadotrophs are seen. At 13 to 16 weeks’ gestation, lactotrophs first appear. During the sixth gestational month, innervation of the neurohypophysis with axonal processes from the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei takes place.

The differentiation of the oral ectoderm into the terminal anterior pituitary cell types with expression of hormones and receptors is under the control of a large complement of genes and transcription factors (eFigure 21-17). Several excellent reviews discuss the role of these factors in pituitary organogenesis in more detail (

29,

30,

31,

32). The physiology of the different cell types, their specific hormones, and mechanisms of action of these hormones are beyond the scope of this chapter, but is detailed by others (

26,

27,

30,

32,

33).

Developmental Disorders

Anomalies in pituitary gland development are outlined in

Table 21-1 (

34). Agenesis, complete absence, of the pituitary gland is rare as an isolated finding. Isolated agenesis of the pituitary has been noted in infants of diabetic mothers, as a presumed form of diabetic embryopathy. Pituitary dysfunction in neural tube defects is well documented. Agenesis can be associated with other midline and craniofacial abnormalities (

27). In most cases of human holoprosencephaly, a hypoplastic gland can still be found in contrast to findings in animal studies (

35). In the presence of pituitary agenesis, the thyroid gland, the adrenal glands, and gonads are expectedly diminutive. The posterior pituitary or neurohypophysis may be present.

Hypopituitarism, defined as diminution or absence of one or more anterior pituitary hormones, is estimated to occur in 1:4,000 to 10,000 live births. In general, isolated hormone deficiencies and combined pituitary hormone deficiencies (CPHDs) can be distinguished. Hypopituitarism can be the result of developmental defects or a rare secondary effect of traumatic brain injury, treatment for childhood cancer, or meningitis (

5,

36,

37,

38). Hypopituitarism can also be the result of neoplastic and inflammatory processes discussed in detail below. The complex development of the pituitary with contribution of two separate embryonic tissues is guided by a number of cellular signals (

Table 21-2). Disruption in signals that regulate the early steps of this development results in syndromic defects with variably associated CNS, eye, and peripheral manifestations. This is in contrast to defects in signals guiding later steps of development, differentiation, and function that may cause selective hormone deficiencies.

Early signals include

Lhx3,

Lhx4, and the sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway (

Table 21-2). Mutations in

Lhx3 and

Lhx4 result in aplasia or hypoplasia of the anterior pituitary and the intermediate lobe as well as other manifestations. These may include a short rigid spine and hearing loss (

Lhx3) or cerebellar abnormalities and Chiari malformation (

Lhx4). Holoprosencephaly can be the result of many different mutations (

Chapter 10—Nervous System). Disruption of SHH signaling is a common cause. Mutations in

GLI2, a factor in the SHH pathway, have been shown to cause congenital hypopituitarism in isolation or in association with other craniofacial anomalies and polydactyly (

39,

40). The importance of

SHH mutations as the cause of hypopituitarism in humans is less clear than it appears to be in animal studies (

40).

Mutations in

HSEX1,

SOX2, and

SOX3 are linked to septooptic dysplasia with pituitary hypoplasia, midline forebrain defects, and optic nerve hypoplasia.

OTX2 mutations can cause anophthalmia and pituitary defects (

41). The transcription factors PROP1 and POU1F1 are expressed during pituitary development. Mutations in either of these result in CPHD. Some mutations disrupt isolated pituitary hormones. Isolated GH (growth hormone) deficiency has been linked to mutations in the

GH1 gene encoding growth hormone or the gene encoding the GHrH receptor, but also

SOX3 and

HESX1. Congenital deficiency of ACTH has been linked to

TBX19 mutations. Kallmann syndrome results from

FEZH mutations causing failure of GnRH neurons to develop (

42).

Other syndromes with hypopituitarism include MELAS syndrome, Rieger syndrome, trisomy 18, trisomy 13, Pallister-Hall syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Fanconi anemia, and ataxia-telangiectasia.

Anencephaly is characterized by the presence of anterior pituitary tissue within the mass of cerebrovascular tissue (eFigure 21-25A, B). The presence of somatotrophs, lactotrophs, and gonadotrophs is demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Corticotrophs and thyrotrophs present in the pituitary in the second trimester disappear owing to lack of hypothalamic stimulation during the third trimester. A distinct neurohypophysis is absent. The adrenal glands are hypoplastic at birth (eFigure 21-25C, D).

Ectopia of anterior pituitary type tissue is common and invariably an incidental finding typically in the roof of the nasopharynx or as a pharyngeal pituitary. Persistence of

Rathke pouch in the roof of the oronasopharynx, the source of the pharyngeal pituitary gland, has been reported in a number of conditions, including the anencephalic fetus, spina bifida, trisomy 18, and Meckel syndrome. Ectopia of the posterior pituitary has been associated with mutations in genes responsible for pituitary organogenesis (eFigure 21-18) (

43). Ectopic pituitary adenomas (PAs) are documented in the suprasellar region, clivus, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses mainly in adults, but also in children.

Rathke cleft cysts may become symptomatic because of compression of intrasellar or suprasellar structures. Rare cases present with growth retardation in children (the socalled pituitary dwarfism) (eFigure 21-19) or central precocious puberty. Morphologically, these exhibit similar morphologic features as those found with colloid cysts: the cyst is filled with thickened mucoid secretions or dark fluid (eFigure 21-26) and lined by ciliated columnar or low cuboidal epithelium. Microscopic incidental cystic rests with similar morphologic features are a common incidental finding in the pars intermedia in 2% to 26% of autopsies. Other cystic lesions in the region of the pituitary include craniopharyngioma (CRP) and intrasellar arachnoid cyst. A distinguishing feature of the CRP is mixed cystic and solid areas with the palisading and squamoid-type epithelium (

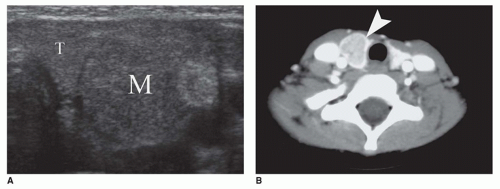

Figure 21-2A, B). Because CRP and Rathke cleft cyst have a shared histogenesis, ciliated columnar epithelium may be seen on occasion in a CRP. Abscess formation and hypophysitis are rare complications in Rathke cleft cysts.

Pituitary duplication is a rare disorder that is ascribed to a duplication of the prechordal plate and anterior aspect of the notochord. Two distinct pituitaries, each with its own stalk, are the typical presentation. This anomaly has been seen with partial twinning, median cleft facial syndrome, precocious puberty, and fetal exposure to meclizine (teratogenic effect). A midline hypothalamic mass of disorganized neurons is accompanied by other midline developmental anomalies, including a duplicated sella, cleft palate, hypertelorism, agenesis of corpus callosum, and vertebral anomalies. Nasopharyngeal teratomas have been reported in association with pituitary duplication in infancy.

Empty sella syndrome (ESS) is usually an incidental finding in young children in contrast to adults. The primary form of ESS results from a defect in the diaphragm covering the opening to the sella turcica, with arachnoid tissue extending through the diaphragmatic defect. Increased CSF pressure leads to enlargement of the sella turcica and compression of the pituitary gland along the floor of the sella turcica, giving the appearance of an empty sella turcica (eFigures 21-27 and 21-28). Pituitary infarction, pituitary atrophy from a tumor, other mass lesion, and prior hypophysectomy account for secondary ESS.

Acquired Disorders

Inflammatory and infiltrative disorders are known to involve the pituitary gland including infections, noninfectious inflammatory conditions, and infiltrative processes. Examples of these diseases are congenital syphilis, mycobacteriosis, lymphocytic-granulomatous hypophysitis, LCH, sarcoidosis (

44), Wegener granulomatosis (

45), iron overload, storage disorder, Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), and Hurler syndrome.

Lymphocytic hypophysitis was first described as a disease of pregnant woman presenting with hypopituitarism. This condition is now recognized as occurring in other settings, including children as young as 9 years of age, but is generally uncommon in children. It is regarded as an autoimmune condition, because of its association with Hashimoto or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (CLT). The adenohypophysis (lymphocytic adenohypophysitis) and neurohypophysis (lymphocytic infundibuloneurohypophysitis) may be involved. In general, the designation of lymphocytic hypophysitis is used to describe both conditions. The pituitary is enlarged with a firm consistency and contains an inflammatory infiltrate of small lymphocytes intermixed with plasma cells (eFigure 21-29A to C). Eosinophils and some macrophages are also seen. Fibrosis is common, but may not be apparent in a small biopsy. Hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, and mass lesion symptoms are the usual clinical manifestations in both children and adults. Because the pituitary and sella are enlarged, a PA is often the clinical impression.

Granulomatous hypophysitis with epithelioid or caseous granulomas has the differential diagnosis of infection (tuberculosis), sarcoidosis, rupture of Rathke cleft cyst, LCH, and idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis. Granulomas are not a feature of lymphocytic hypophysitis, although a nosologic and etiologic relationship may exist between these idiopathic inflammatory disorders.

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation (cholesterol granuloma) of the sellar region is an inflammatory reaction characterized by cholesterol clefts, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, hemosiderin deposits, fibrosis, foreign body giant cells, histiocytes, and eosinophilic necrotic debris. Although xanthogranulomatous inflammation may be associated with an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (CRP), this pattern has also been observed in idiopathic cases primarily in adolescents and young adults lacking a CRP component.

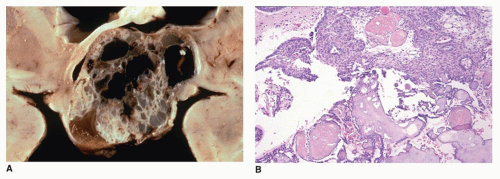

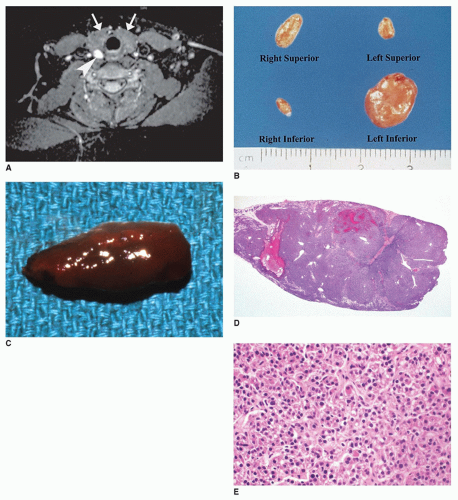

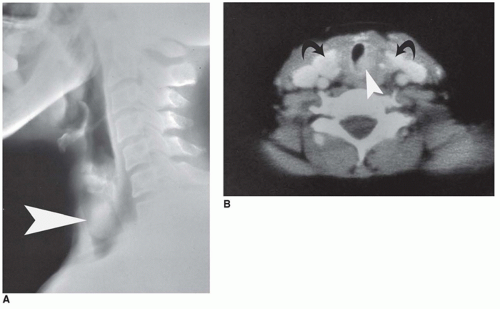

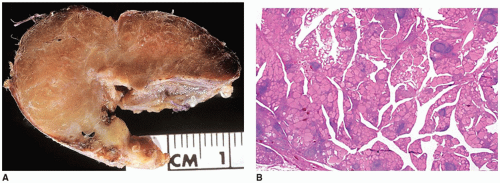

Vascular lesions with hypopituitarism are uncommon in children, but hemorrhagic infarction of a pituitary macroadenoma, referred to as pituitary apoplexy or pituitary tumor apoplexy, is one such example (

Figure 21-3A, B) (

46). Pediatric cases of pituitary apoplexy may be milder than in adults, having a more indolent course and associated with a more favorable outcome (

47). Sheehan syndrome is the result of severe maternal intrapartum hypotension leading to pituitary infarction in the postpartum period. Presumed ischemia of the pituitary in sickle cell crisis is associated with decreased growth hormone secretion and impaired growth in affected children. Some cases of septo-optic dysplasia, classified as a developmental anomaly, are thought to represent a vascular disruption of the anterior cerebral artery. Vascular lesions due to stalk transection may occur secondary to trauma.

Nonneoplastic cysts identified in children on radiologic studies are not clinically evident unless the sella turcica is expanded, which leads to hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus. Cystic dilatation of Rathke pouch remnants is common; however, these cysts are usually less than 5 mm in diameter (eFigures 21-19 and 21-26). Rathke cleft cysts arise from the squamous epithelium of the Rathke cleft and infrequently become enlarged with symptoms resembling a CRP. Arachnoid and dermoid cysts are also regarded by some as congenital defects. An intrasellar arachnoid cyst must also be distinguished from a CRP.

Pituitary hyperplasia is a nonneoplastic proliferation of one of the functional adenohypophyseal cell types. It is a polyclonal proliferation leading to pituitary enlargement and may produce a suprasellar mass. In children, somatotroph hyperplasia is reported in the McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) and gigantism. Pituitary hyperplasia has also been reported in primary hypothyroidism. During pregnancy, the pituitary gland doubles in size due to the proliferation

of the lactotrophs (responsible for prolactin secretion) and decreases in size postpartum (

27).

Pituitary adenoma (PA) is a monoclonal neoplasm of the adenohypophysis. Up to 10% of all PAs present in the first two decades of life. Over 90% of these are diagnosed in the second decade, and less than 10% before 10 years of age. Between 15 and 19 years of age, PAs are the most common CNS tumor, being twice as common in girls as boys (

26,

46,

48,

49). Reports of adenomas occurring in children less than 4 years of age are uncommon. The youngest example of an ACTH-secreting PA occurred in a 7-month-old infant with Cushing disease. Most PAs are sporadic, but a number of cases are linked to familial mutations (

Table 21-3). About 20% of PAs in the pediatric populations are the result of

AIP mutations (

50,

51,

52). Most of the AIP-associated PAs express growth hormone with or without prolactin. Other cases are linked to germline mutations in

MEN1,

VHL,

SDHB,

SDHC,

SDHD, and

PRKAR1A (Carney complex) (

50,

53,

54,

55). Cases with

SDH subunit mutations typically exhibit prominent cytoplasmic vacuolation (

55).

In terms of function, the majority of PAs in children are prolactinomas (53%). The remaining tumors are ACTH-secreting tumors (31%), growth hormone-secreting tumors (9%), and endocrine-inactive (null cell tumors) (3%) (

48,

56,

57). ACTH-secreting adenomas are more common before puberty, in contrast to prolactinomas and growth hormone-secreting tumors, which are more common after puberty.

The clinical manifestations of PAs in children are variable. Headaches and visual field defects are the most common clinical manifestations of mass effect. Prolactinomas may result in amenorrhea and galactorrhea in girls and gynecomastia and hypogonadism in boys. Children with ACTH-secreting adenomas present with Cushing disease. Children with somatotropin or growth hormone-secreting adenomas present with gigantism.

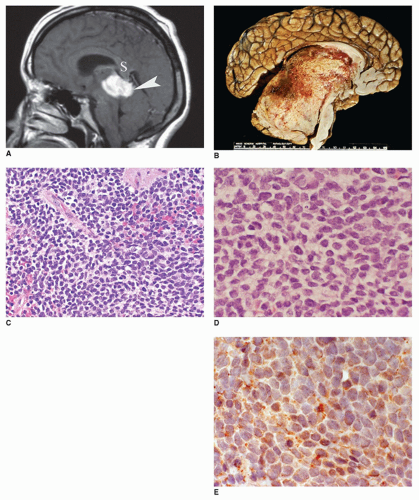

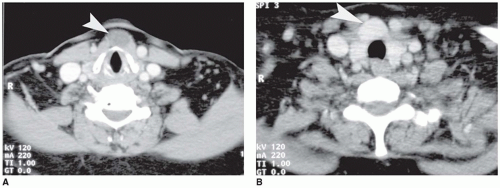

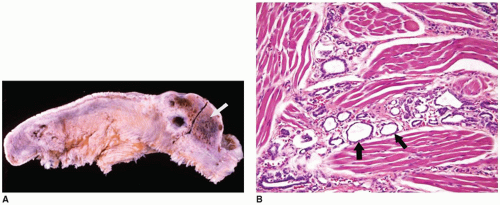

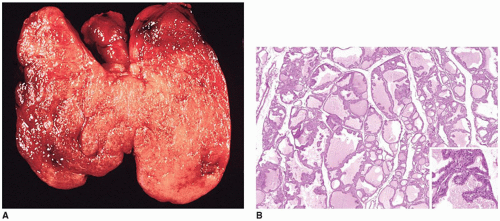

Most prolactinomas, growth hormone-secreting tumors, and endocrine-inactive PAs are macroadenomas (>10-mm tumors in diameter) (

Figure 21-4A, B). In contrast, ACTH-secreting adenomas are more often microadenomas (<10-mm tumor in diameter) (eFigures 21-30 and 21-31) (

58). Macroadenomas are more common than microadenomas in children, consistent with the fact that prolactinomas are more common than ACTH-secreting tumors. PAs are classified on the basis of five-tiered features: endocrine activity, imaging studies and operative findings, histology, immunohistochemistry, and ultrastructure (

59). PAs are soft and gray-red and measure less than or equal to 2 cm. On the basis of imaging criteria, four grades of tumors are recognized: grade I (<l cm in diameter), grade II (intrasellar lesion >1 cm in diameter or with suprasellar expansion without invasion), grade III (small or large locally invasive tumor with bony invasion of the sella turcica), and grade IV (large invasive tumor involving the bone, hypothalamus, or cavernous sinus) (

26). Larger aggressive tumors are more likely to be cystic, hemorrhagic, and necrotic (

Figure 21-3A, B). One or more concurrent histologic patterns (diffuse, trabecular, papillary) may be evident. The degree of cellularity is variable from highly cellular to more scantily cellular tumors with hyalinized or amyloid-like stroma. The tinctorial quality of the cytoplasm has given rise to the characterization of PAs as basophilic, acidophilic, or chromophobic with some limitations. The tumor cells are generally rounded with some occasional spindling with the rounded central or eccentric nuclei. The tumor cells may have plasmacytoid qualities in the presence of an eccentric nucleus and prominent basophilic, acidophilic, or amphophilic cytoplasm. Prolactinomas are typically composed of chromophobes or slightly acidophilic cells with a solid or papillary pattern and hyalinized stroma with or without microcalcifications (

Figure 21-4C, D, eFigure 21-32). PAs tend to lack a capsule (eFigure 21-30). Electron microscopy

and immunohistochemistry are adjuncts to characterize these tumors (

Figure 21-4E, eFigure 21-33). In addition to specific hormonal immunostaining, PAs are positive for SYN, CHR, and NSE (

30).

In terms of clinical behavior, macroadenomas are more likely to be invasive in contrast to the smaller expansile microadenomas. It is debatable whether PAs in children are more aggressive than their adult counterparts. Invasive adenomas are characterized by extension into dura, bone, and cavernous sinus. These features are generally not well documented in the pathologic examination. There is a certain degree of correlation between proliferative activity, as determined by MIB-1 (Ki67) nuclear immunostaining, and observed invasiveness of the tumor.

Pituitary blastoma is a rare pediatric lesion linked to germline mutations in

DICER1, composed of various cell types, including primitive Rathke-type epithelium, and folliculostellate and secretory adenohypophyseal cells (

60,

61).

Pituicytoma is a rare neoplasm arising from specialized glial cells, pituicytes, in the neurohypophysis, presenting as a lowgrade spindle cell lesion with glial differentiation (

62).

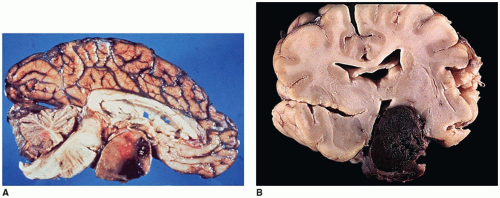

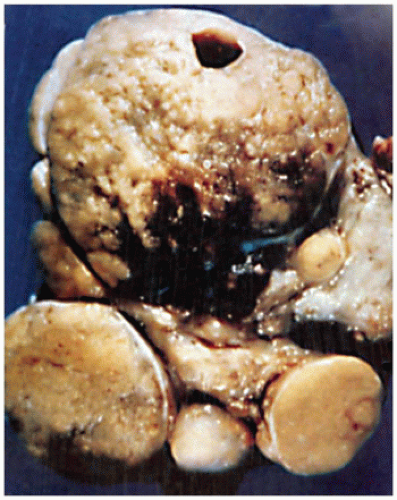

Craniopharyngiomas (CRPs) are thought to be derived from remnants of the Rathke pouch and account for 3% to 4% of primary CNS tumors in children (

63). Generally, the tumor is found in the suprasellar region (

Figure 21-2A, eFigures 21-34 to 21-36). Rare cases may be parasellar or ectopic in the pineal gland region. The differential diagnosis includes PA, infection, inflammatory processes, vascular malformations, and Rathke cleft cyst. Imaging is helpful in distinguishing among CRPs, PAs, and Rathke cleft cysts.

CRPs in children are most commonly diagnosed between 5 and 14 years of age with no gender predilection (

63). Tumors occurring during infancy are uncommon. Compressive symptoms, including pituitary dysfunction with retarded growth, are the principal clinical manifestations (

64). Diabetes insipidus due to posterior pituitary involvement is infrequent. A calcified cystic suprasellar mass is characteristic on CT and MR scans (eFigure 21-36). Surgical resection may be followed by a recurrence (

2). The gross specimen consists of cyst fragments with a yellow to dark brown appearance. Fluid contents have a dark oily appearance (crankcase) with cholesterol crystals and fragments of keratinous debris. In children, the histologic features are typically adamantinomatous or ameloblastic. A papillary squamous pattern is seen more often in adults (

26,

29). Beta-catenin mutations are seen in the adamantinomatous pattern (

26,

29), while the papillary squamous pattern is linked to BRAF mutations (

65). In adamantinomatous CRPs, epithelial lobules are arranged in a cloverleaf-like pattern. Palisading of the cells adjacent to the randomly distributed fluid-filled cystlike spaces is a characteristic feature. Aggregates of necrotic, keratinized cells, or “wet” keratin accompanied by dystrophic calcification, are other features (

Figure 21-2B, eFigure 21-37). Fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and cholesterol clefts are observed in the solid areas. A xanthogranulomatous reaction is prominent in some cases, especially with a ruptured cyst. Although CRPs are regarded as clinically benign, adherence to the hypothalamus and extension into the surrounding brain parenchyma occur in some cases. Cytokeratin expression has been used to distinguish CRP from Rathke cleft cyst. An uncommon CRP variant is one with adamantinomatous features together with elements of a PA, a so-called collision tumor. In many of these “collision tumors,” the adenoma is nonfunctional; however, immunohistochemistry displays gonadotropin, prolactin, ACTH, and TSH staining.

Other tumefactive lesions of the pituitary and sellar region include the ganglion cell tumor (so-called gangliocytoma), LCH, granular cell tumor, RDD, and salivary gland hamartoma. Gangliocytomas are regarded as neoplasm by most observers, but hamartoma by others. These may be found in association with PAs, pituitary hyperplasia, or as a distinct mass. These lesions have been classified as either mixed adenoma-gangliocytoma or pure gangliocytoma.

In addition to PA and CRP, the midline region of the sella and suprasellar area is another common anatomic site besides the pineal region for intracranial germ-cell tumors. 60% to 70% of all primary intracranial germ-cell tumors arise in the pineal region and 30% to 40% in the sellar or suprasellar area. Cases associated with prominent inflammatory infiltrates may be mistaken for an inflammatory disease process if the neoplastic cells are not appreciated. Visual field defects, diabetes insipidus, and panhypopituitarism are the principal clinical manifestations of suprasellar germ-cell tumors.

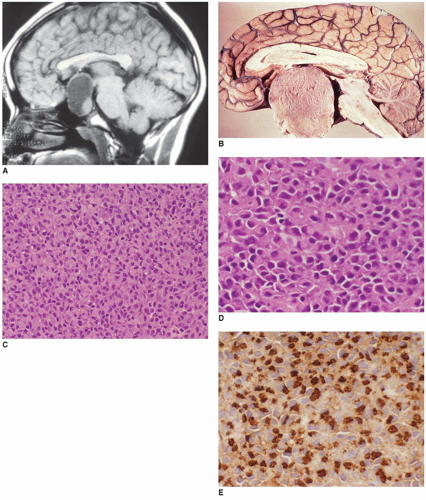

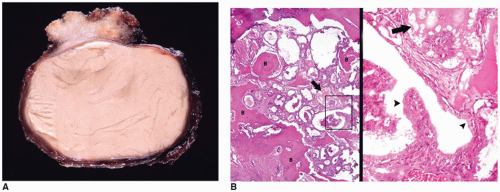

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is well documented in the CNS with involvement of brain parenchyma and/or the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, causing central diabetes insipidus (

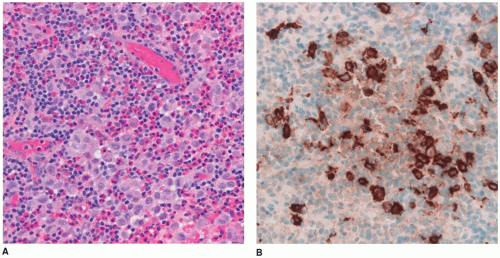

66). The pituitary stalk is thickened on imaging studies (eFigures 21-21 to 21-23). Almost 15% of those with multisystem LCH have hypothalamic-pituitary involvement. There is limited documentation of the pathology in such cases because the diagnosis is usually established on the basis of a biopsy from a more accessible site. A mixture of Langerhans cell histiocytes, characterized by large, convoluted, and indented nuclei, that are CD207 (langerin, more specific) and CD1a (less specific) positive, mixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils, is diagnostic for LCH (

Figure 21-5A, B, eFigure 21-38A to C).

RDD has craniospinal manifestations in a minority of cases, including the sellar-suprasellar region. In 50% of cases, RDD is limited to this site.

Salivary gland rest or heterotopia is an incidental microscopic finding on the surface of the posterior pituitary. Other neoplasms of presumed salivary gland type, granular cell tumor of the pituitary and pituitary stalk, leukemia, lymphoma, and metastatic involvement of the pituitary are restricted to adults in most cases. Both primary and metastatic germ-cell neoplasms also occur in the pituitary.