Fig. 40.1.

Gross anatomy . (A) A diagrammatic representation of the cut surface of the distal penis. Anatomical compartments are the glans (G), coronal sulcus (COS), and foreskin (F). Urethra (U) is ventral and terminates in the meatus urethralis (M). (B) Cut surface of a partial penectomy specimen with a small carcinoma in the coronal sulcus (CA) showing the glans anatomical layers: epithelium (E), lamina propria (LP), corpus spongiosum (CS), tunica albuginea (TA), and corpus cavernosum (CC).

♦

The foreskin covers the glans. It presents an inner (mucosal) surface in direct contact with the glans mucosa and an outer (cutaneous) surface that is in continuity with the skin of the shaft. The interface between the inner and outer surfaces forms the preputial ring. The frenulum connects the foreskin to the ventral portion of the glans corona

♦

Three types of foreskin are described: In the long type, the foreskin completely covers the glans; in the middle type, the preputial ring is located between the meatus urethralis and the glans corona, partially covering the glans; in the short type, the glans remains uncovered, and the preputial ring is located at the level or below the glans corona

♦

The penile shaft is covered by skin with an underlying loose connective tissue, the penile (Buck) fascia. The penile erectile tissues are distributed in two dorsal columns of corpora cavernosa and one ventral column of corpus spongiosum. A dense connective tissue, the tunica albuginea, encases both corpora cavernosa. The corpora cavernosa ends approximately at the level of the glans corona, and the corpus spongiosum expands to form the glans

♦

Penile urethra extends ventrally from shaft to the meatus urethralis, and it is encased by the corpus spongiosum

Microscopic Features

♦

There are three anatomical compartments each with especial anatomical layers, important for the surgical pathologist. They are the glans, the foreskin, and the coronal sulcus (Fig. 40.1A, B)

♦

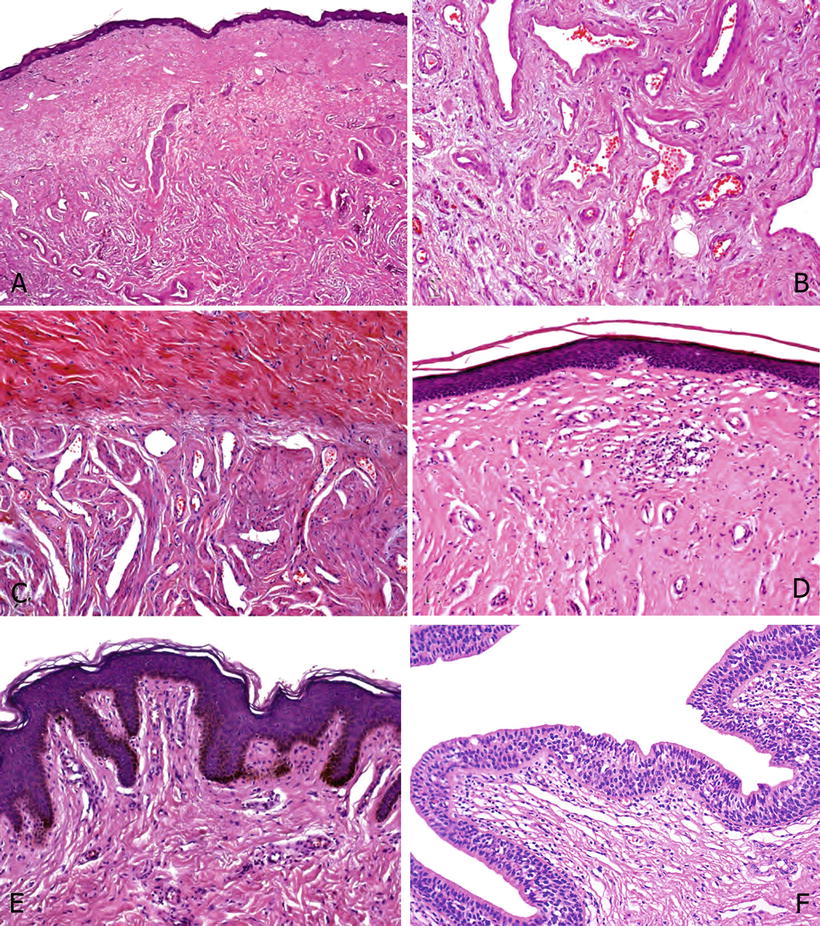

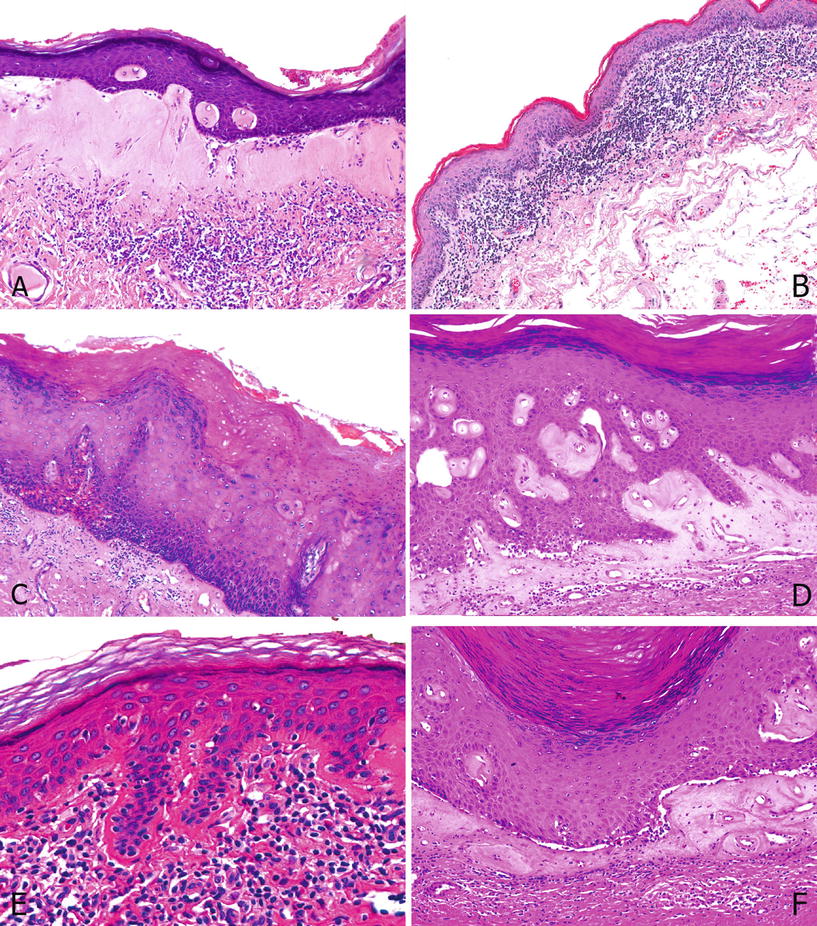

Glans: From surface to deep tissues, the layers are in uncircumcised patients nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, lamina propria, corpus spongiosum, and corpora cavernosa, each separated by the tunica albuginea (Fig. 40.2A–C)

Fig. 40.2.

Glans. (A) From surface to deep tissues, there are the squamous epithelium, lamina propria, and corpus spongiosum. (B) A closer view of corpus spongiosum shows erectile tissues; the vessels are irregularly shaped and separated by abundant fibrous matrix. (C) At the top, there is a dense collagenous tissue corresponding to the tunica albuginea. Below note the slit-like vascular lumina surrounded by thick bundles of smooth muscle, typical of corpus cavernous erectile tissue. (D) The foreskin inner mucosa is formed by a nonkeratinized squamous epithelium similar to that covering the glans and the coronal sulcus. Note the almost flat epithelial base and the absence of pigmented keratinocytes. (E) The foreskin outer surface is covered by a slightly keratinized squamous epithelium. Note the irregular rete ridges of the basal epithelium and the easily recognized pigmentation of the basal cells. (F) Penile urethra: Penile urethral urothelium is composed of two tissue layers, more basal stratified immature cells and a single cylindrical cell layer at the surface.

♦

Foreskin: From inner to outer surfaces, there are the nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, lamina propria, dartos, and skin (Fig. 40.2D, E)

♦

Coronal sulcus: From inner surface to fascia, there are the nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, dartos, and penile fascia

♦

A cross section of the penile shaft, from outer to inner layers, shows the skin, the penile fascia and dartos, the tunica albuginea, and the corpora cavernosa

♦

Penile urethra (Fig. 40.2F) is composed of the following microscopic layers: urothelium, lamina propria, corpus spongiosum, and penile fascia

Congenital Anomalies

Hypospadias

♦

Hypospadias are the most common congenital anomaly of the male external genitalia, with an incidence of 3–5/1,000 male births. It is characterized by an incomplete fusion of the urethral folds with abnormal opening of the urethra along the ventral aspect of the penis

♦

Most of the time, the urethral opening takes place near the glans, along the shaft, or near the penile base in the form of slits of variable length. Extension to the scrotal raphe is exceptional. In rare cases, the urethral fusion fails, and the distal urethra remains open through its entire length, from the scrotal raphe to the meatus urethralis

♦

Other anomalies found associated with hypospadias include absence of the foreskin, cryptorchidism, inguinal hernias, and chordee. The term chordee makes reference to a bending of the penis, congenital in hypospadias, and caused by a distal maldevelopment of the penile fascia. Strictures can develop as a consequence of hypospadias, with the consequent impaired ejaculation and secondary infertility

Epispadias

♦

Epispadias is a very rare abnormality, with an incidence of 1/30,000 male births. It is characterized by the opening of the penile urethra at the dorsal aspect of the penis, caused by a misplaced development of the genital tubercle, which forms in the region of the urorectal septum instead of the cranial margin of the cloacal membrane

♦

As a consequence of this displacement, a portion of the cloacal membrane is located cranially to the genital tubercle. When this membrane ruptures, the urogenital sinus outlet extends through the dorsal surface of the penis. Most of the cases of epispadias are associated with bladder exstrophy in which the lower portion of the abdominal wall fails to close around the cloacal membrane. There is subsequent exposure of the bladder mucosa to the outside environment

♦

Other associated abnormalities include cryptorchidism, renal agenesis, and ectopic kidney. Urethral opening may be constricted, and the location may impair normal ejaculation and insemination, resulting in inferti lity

Aphallia

♦

Aphallia, also named penile agenesis, is a rare condition detected in 1/10,000,000 male births and caused by a failure in the embryologic development of the genital tubercle

♦

Scrotal sacs are present but no penile shaft is observed. Aphallia tends to be associated with other malformations of the urogenital tract, such as cryptorchidism, imperforate anus, renal agenesis and other renal malformations, and with musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary defect s

Micropenis (Hypoplasia)

♦

Hypoplasia of the penis implies the presence of a small penis with a size of two or more standard deviations bellow the mean adjusted by age. In these cases, the ratio of the penile shaft length to its circumference is normal. The length of the penis should be measured along the dorsal surface of the shaft from the pubis to the tip of the glans and with the penis stretched to resistance

♦

Penile hypoplasia is usually associated with endocrine abnormalities causing insufficient androgen stimulation for growth of the external genitalia. Primary hypogonadism explains most of the cases, hypothalamic and pituitary dysfunction the remainder. In some cases, no endocrine abnormality is detected and the cause remains unknown

Other Congenital Malformations

♦

In webbed penis , a not uncommon anomaly, the penis is normal but the skin of the scrotal sacs extends to the penile ventral surface and hides it. Concealed penis makes reference to the presence of an otherwise normally developed penis, hidden under the adipose tissue of the suprapubic area, scrotum, perineum, or thigh

♦

The asymmetric development of one corpus cavernosum, either hypoplasia or hypertrophy, can cause a congenital lateral curvature of the penis. Areas of fibrosis affecting the erectile tissues can produce torsions of the penile shaft

♦

The presence of a double penis (diphallus) is consequence of the division of the genital tubercle in two, with the subsequent penile duplication. It is associated with other congenital anomalies, including hypospadias, renal agenesis, imperforate anus, cardiac defects, and others

Benign Tumors and Tumorlike Conditions

Condyloma Acuminatum

General Features

♦

Condyloma acuminatum is a human papillomavirus (HPV)-related lesion affecting the anogenital area of sexually active young and middle-age males

♦

Most commonly, it is caused by genotypes 6 and 11, although others can also be involved

Macroscopic

♦

The most common anatomical site affected is the glans. The foreskin, the shaft, the meatus urethralis, and the distal urethra are other frequently involved sites

♦

The lesion is frequently multicentric (Fig. 40.3A)

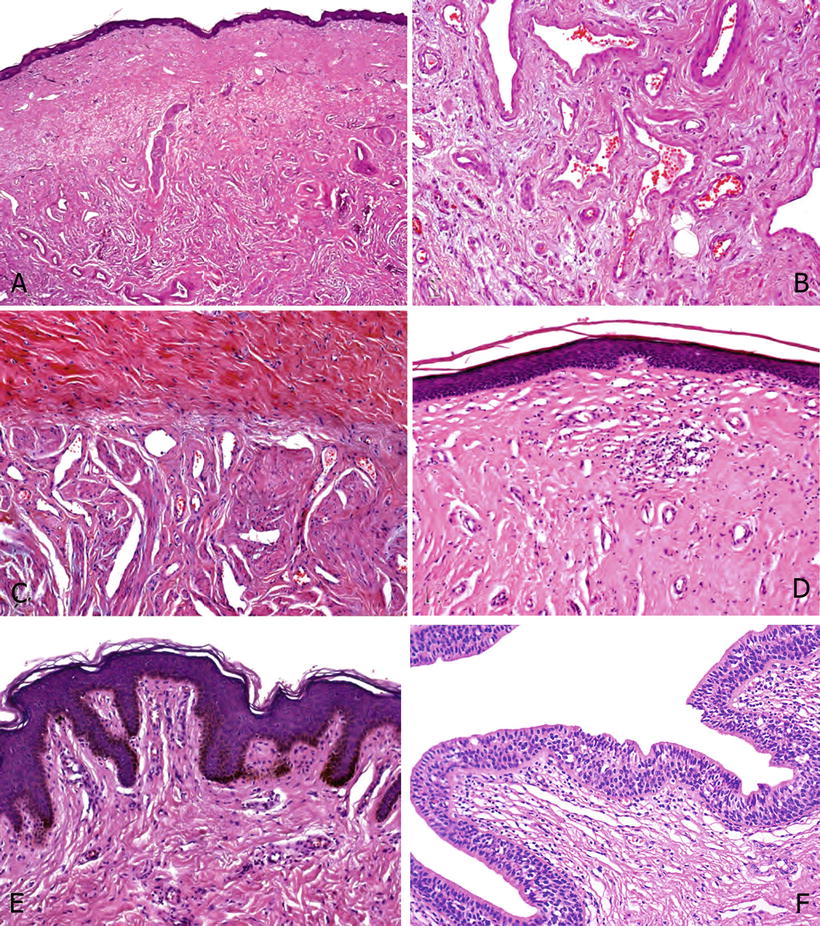

Fig. 40.3.

Co ndyloma acuminatum. (A) Circumcision specimen with multicentric elevated white-gray lesions with a cauliflower-like appearance. (B) Papillomatosis, acanthosis, lack of atypias, and fibrovascular cores are typical features of condyloma acuminatum. (C) Koilocytes are recognized at the surface of the papillae. There is no cytological atypia. Note the broad and flat interface between tumor and stroma. (D) Prominent parakeratosis. Koilocytosis is found at the tip of the papillae.

♦

Clinically depicts a typical cauliflower-like papillary appearance

♦

The size is variable, ranging from unapparent millimetric lesions to tumors larger enough to cause clinical concern about their nature

Microscopic

♦

There are papillomatosis, acanthosis, parakeratosis, and hyperkeratosis. Papillae have fibrovascular cores (Fig. 40.3B)

♦

The hallmark of the lesion is the koilocyte, a superficially located and conspicuous polygonal cell with wrinkled nuclei, clear perinuclear halos, and frequent binucleation (Fig. 40.3C, D). The interface between the lesion and the stroma is always sharp and well defined. Atypias are not presen t

Giant Condyloma

General Features

♦

It is a rare long-standing verruciform tumor, which can sometimes be confused with warty or verrucous carcinomas. Most of the cases are associated with low-risk HPV

♦

Affected males are older than those with typical condyloma acuminatum, but younger than those with warty carcinomas

♦

Malignant transformation may occur

Macroscopic

♦

The lesion preferentially affects the foreskin and coronal sulcus, but they also occur in the glans. It is larger than typical condyloma acuminatum, with an average size of 5–10 cm

♦

It is a large white-gray cauliflower-like exophytic tumor. The cut surface reveals a distinct sharply delineated boundary of tumor and underlying stroma

♦

Usually unicentric

♦

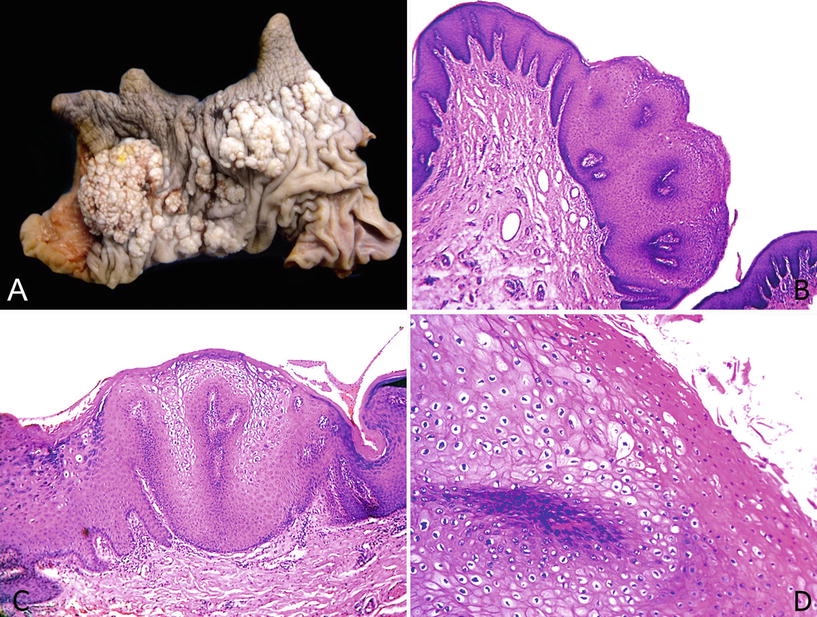

Microscopically, there is a similarity with typical condyloma acuminatum, but the papillomatosis is more exuberant, and there is endophytic expansion into the subjacent tissue (Fig. 40.4A–C)

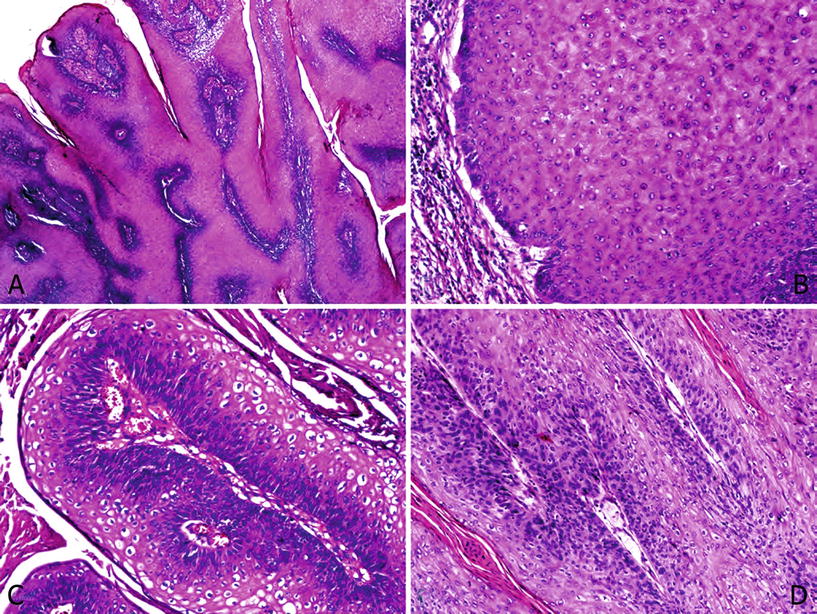

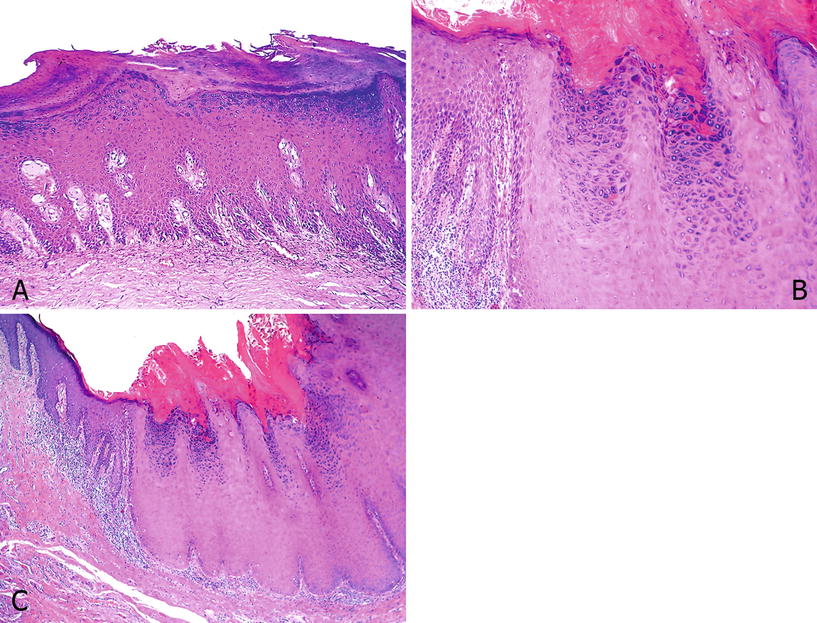

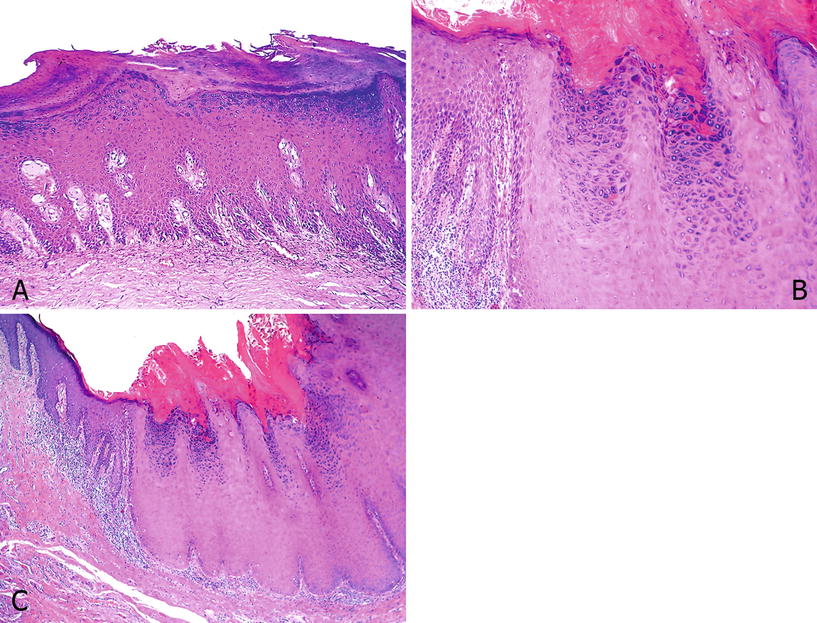

Fig. 40.4.

Giant condyloma with malignant transformation. (A) Features similar to condyloma acuminatum, but papillomatosis is more prominent and complex. (B) No cytological atypias are recognized and the tumor–stroma interface is broad. A chronic stromal reaction is seen. (C) Marked clear cell koilocytosis is observed. (D) The presence of epithelial atypia located at the base of the papillae in an otherwise usual giant condyloma defines the lesion as an “atypical condyloma”.

♦

“Atypical giant condyloma” is the denomination given to a giant condyloma with more cytological atypias than those expected for this lesion, but not fulfilling the morphological criteria of warty carcinomas. Cases of malignant transformation may occur (Fig. 40.4D)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The differential diagnoses include warty, verrucous, and papillary carcinomas (Table 40.1). Warty carcinomas are characterized by condylomatous papillae, cell pleomorphism and jagged infiltrative tumor base, both features absent in giant condyloma. In verrucous carcinoma, the fibrovascular cores are unapparent, and in papillary carcinomas, the tumor base is jagged and irregular. Neither of these two aforementioned variants exhibit koilocytic chan ges

Table 40.1.

Differential Diagnosis in Penile Verruciform Tumors

Feature | Giant condyloma | Warty carcinoma | Verrucous carcinoma | Papillary, NOS carcinoma | Carcinoma cuniculatum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Papillae | Arborizing, condylomatous, nonundulating, rounded | Long and undulating, condylomatous, complex | Straight | Variably complex | Straight |

Fibrovascular cores | Prominent | Prominent | Rare | Variably present | Rare |

Tumoral base | Regular, broad, and pushing | Rounded or irregular and jagged | Regular, broad, and pushing | Irregular and jagged | Regular, broad, and pushing |

Histological grade | 1–2 | 1–2 | 1 | 1–2 | 1–2 |

Koilocytosis | Present at surface, rarely diffuse but not pleomorphic | Prominent and diffuse, pleomorphic | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Growth pattern | Exophytic | Predominantly exophytic with a variable endophytic component | Exophytic | Predominantly exophytic with an endophytic component | Exophytic–endophytic |

Nodal metastases | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

HPV related | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

♦

Malignant transformation may be found in giant condylomata. The malignant component exhibits the aspect of a squamous cell carcinoma of the usual type and, rarely, of the warty or basaloid type

♦

In difficult cases, HPV detection or p16 negativity are required for the diagnos is

Penile Cysts

General Features

♦

Cysts arising i n the penis are uncommon; they can be found anywhere from the urethral meatus to the root of the penis involving glans, foreskin, or shaft. Single cases and case series have been reported by authors that described and classified them according to their histological features, location, and possible pathogenesis

♦

The most common types of penile cysts are the epidermal inclusion cyst and the median raphe cysts

Epidermal Inclusion Cyst

♦

They are similar to those occurring elsewhere. The etiology is unknown, but in some cases, they are associated with hypospadias, phimosis, or penile enlargement surgical procedures. Usually, they are found in young boys and elderly men

♦

In our practice, they are preferentially located in the foreskin, but cases can also be seen at the glans, coronal sulcus, near the frenulum, and, less frequently, the shaft. Most of them do not exceed 1.0 cm in maximum diameter

♦

Histologically, epidermal inclusion cysts are lined by a nonatypical keratinized squamous epithelium surrounding the cyst cavity. Keratin debris fills up the cyst cavity. Keratinization pattern is orthokeratotic with the presence of a more or less evident granular layer. Skin adnexa are absen t

Mucinous Cyst

♦

These cysts arise from ectopic urethral mucosa and are lined by a stratified columnar epithelium with mucinous cells. Preferentially located at the glans or foreskin, they have been described as paraurethral or perimeatal cysts. Latter locations should rise the possibility of a median raphe cyst

Median Raphe Cyst (Urothelial Cyst)

♦

Median raphe cysts are caused by a developmental failure in the closure of the urethral folds and, hence, are always located at the ventral midline of the penis, from near the meatus urethralis to the scrotal median raphe. They usually do not communicate with the urethra. When located near the meatus urethralis, they are referred to as “parameatal cysts”

♦

Due to the appearance of their epithelial lining, they may be considered as urothelial cysts

♦

Median raphe cysts evidenced later in life have been described. Patients present at any age with higher incidence in childhood and lower number of cases seen in the elderly. Cases arising anywhere along the penile–scrotal–perineal ventral midline have been published, although penile lesions are certainly more frequent than rare scrotal and perineal counterparts

♦

Clinically, median raphe cysts manifest as unilocular or multilocular painless lesions, although in occasions they can be associated with local discomfort, dysuria, or even dyspareunia. Sometimes they are traumatized and manifest as painful nodules or ulcerated areas

♦

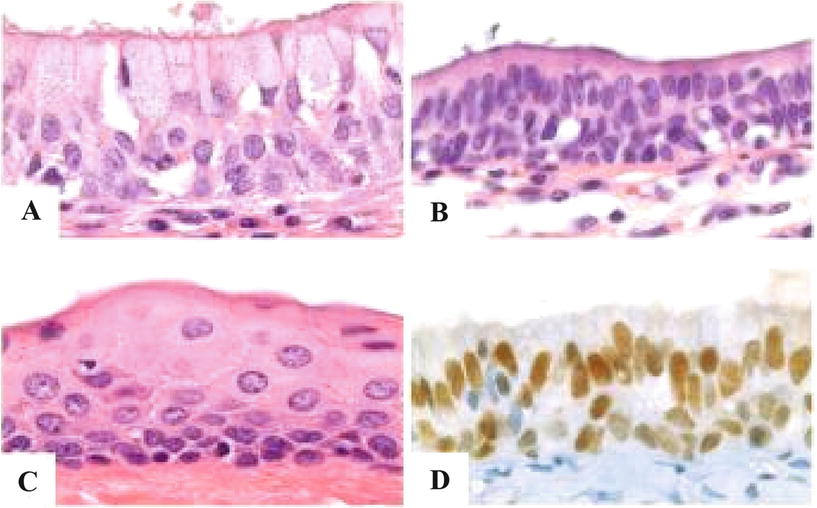

Histologically, the epithelial lining is variegated and can be urothelial-like, nonkeratinized squamous, pseudostratified columnar, mucinous, or apocrine-like (Fig. 40.5A–C). No epithelial atypias should be present

Fig. 40.5.

Median raphe (urothelial) cyst variable epithelial lining. (A) Mucinous. (B) Columnar. (C) Squamous. (D) Immunostain for GATA 3.

♦

The different types of epithelia normally present in the mature urogenital tract can explain this histological diversity, with pseudostratified and stratified columnar epithelium present in the proximal two-thirds of the penile urethra and nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium lining the distal third. Ciliated epithelium in some median raphe cyst has been attributed to metaplastic change, similar to that reported to occur in the penile urethra secondary to local irri tation

Other Rare Cysts

♦

Dermoid cysts have been occasionally reported, and their aspect is identical to that observed elsewhere in the body. The clinical aspect is similar to other penile cysts. Histologically, the cyst is lined by a stratified squamous epithelium with adnexal structures such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles

♦

Lymphatic cysts can also be observed at the penis but they are exceedingly rare. The histological picture is identical to similar cysts elsewhere

Verruciform Xanthoma

General Features

♦

Verruciform xanthomas are rare exophytic penile lesions similar to their oral counterparts. They are the consequence of inflammatory conditions which produce epithelial damage and lipid release into the lamina propria; these lipids are then engulfed by cells of the immune system

♦

Several studies have failed in identifying a causal relationship between verruciform xanthoma and HPV infection

Macroscopic

♦

White-gray verruciform tumor, which can be confused with warty and verrucous carcinomas

Microscopic

♦

There is papillomatosis, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis. A characteristic infiltrate composed of lipid-laden histiocytes (“foamy cells”) is present in superficial lamina propria. Neutrophils are detected in some cases

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Differential diagnosis is with other verruciform tumors, especially verrucous carcinoma. The lack of atypias and the presence of histiocytes favor the diagnosis of verruciform xanthoma. Infectious organisms should also be consid ered

Peyronie Disease

General Features

♦

Peyronie disease is a variant of superficial fibromatosis, which affects primarily the tunica albuginea and secondarily extends to the corpora cavernosa. It affects 1–4% of the males

♦

The etiology is unknown. It has been reported in association with coital trauma, urethral instrumentation, usage of beta-blockers, autoimmune disease, and carcinoid syndrome

♦

An alteration and reduction in the elastic fiber content of the tunica albuginea are the main pathogenic events; these processes secondarily induce similar changes in the erectile tissues of the corpora cavernosa

♦

The disease has a progression phase usually of months of duration and then stabilizes. A minority of the cases present spontaneous regression

Clinical

♦

Most of the patients are in their 50s. The disease is rare before 20 years. Clinically, a penile curvature, more evident during erection, is observed. In some cases, painful erection and dyspareunia are referred

♦

The palpation of the shaft discloses the presence of multiples areas of multinodular indurations, most common over the dorsal aspect of the penis

Macroscopic

♦

The main alterations are observed at the level of the tunica albuginea. There is dense and irregular thickening of this anatomical structure and several fibrotic nodules in the dermis and penile fascia

Microscopic

♦

There are extensive foci of sclerosis centered in the tunica albuginea and extending to the corpora cavernosa. In the sclerotic areas, spindle fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are recognized

♦

Other histolo gical findings include perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, alterations in the erectile vasculature, and calcification/ossification

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Peyronie disease should be distinguished from penile sarcomas and penile metastases. The clinical picture and imaging findings can be similar in these cases

♦

Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration can render a more accurate diagnosis in difficult cases. The previous or concurrent history of malignancy is present in most of the patients with penile metastases

♦

The self-injection of pharmacological substances such as papaverine hydrochloride and phentolamine mesylate can produce secondary fibrosis of the tunica albuginea clinically similar to Peyronie disease. Proper anamnesis is essential in these case s

Papillomatosis of Glans Corona

General Features

♦

A common condition present in about one-quarter of sexually active males and characterized by multiple small papules located at the level of the glans corona. Also named “penile papules” and “hirsutoid papilloma,” it has been linked to an excessive sexual activity

Macroscopic

♦

This condition has a preference for the dorsal aspect of the glans corona, where it presents as multiple painless small papules orderly distributed in two or three columns. The papules are homogeneous in size and shape with a pearly gray surface. In some cases, they can extend to cover most of the glans. Similar lesions have been rarely observed in the foreskin

Microscopic

♦

Histologically, it is like a fibroepithelial papilloma, with squamous epithelium covering a polypoid fibroid lesion

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Clinically, this condition can be confused with condylomata, although the macroscopic features are characteristic. The anatomical location and the regularity of the papules are typical. There is no koilocytos is

Lipogranuloma

General Features

♦

Penile lipogranuloma makes reference to an inflammatory reaction secondary to the local injection of foreign lipidic substances into the penis, such as Vaseline, paraffin, silicone, or wax

♦

Most of the time, the lesion affects exclusively the penis, although in some cases, there is extension to adjacent sites, especially the scrotum

Macroscopic

♦

Beyond the more or less distorted aspect of the organ, sometimes suggesting a neoplasia, no specific gross abnormalities are characteristic of this condition. Areas simulating cysts may occasionally be observed

Microscopic

♦

Penile lipogranuloma is characterized by a prominent inflammatory cell infiltrate and abundant foreign body-type multinucleated giant cells. Sclerosis can sometimes be very prominent, and so the designation of “sclerosing lipogranuloma” is appropriate in these cases

♦

The inflammatory cells surround vacuoles and cyst-like spaces of variable size which correspond to the areas of lipidic materials

Differential Diagnosis

♦

An adenomatoid tumor or a lymphangioma may be considered. The vacuoles in adenomatoid tumor are more homogeneous in size and shape and do not content lipids. The vacuole-like spaces of lymphangioma are lined by endothelium, while in the cyst-like areas of lipogranuloma, there is no epithelial lining

♦

Sclerosing liposarcoma should also be ruled out. The presence of foreign body-type giant cells, the more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, and the absence of lipoblasts are indicative of a lipogranuloma

Penile Melanosis–Lentiginosis

General Features

♦

Penile melanosis and penile lentiginosis are nonneoplastic hyperpigmented lesions that can clinically be confused with benign and malignant melanocytic proliferations. They are usually found in the glans, the shaft, or both

Macroscopic

♦

Penile melanosis usually manifests as a large, single, pigmented macule with irregular borders, while penile lentiginosis is characterized by the presence of multiple hyperpigmented small-to medium-size lesions with uniform or variegated pigmentation

Microscopic

♦

The histological picture is similar in both entities. Melanocytic hyperplasia with more or less prominent hyperpigmentation of basal layers in an otherwise normal epidermis is the typical finding. Stromal melanophages can occasionally be seen, especially in penile lentiginosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

These hyperpigmented lesions should be distinguished from acral malignant melanoma. The diagnosis is made by histological examination of the lesion. The presence of atypia indicates a malignant proliferatio n

Precursor Lesions and Precancerous Conditions

Squamous Hyperplasia

General Features

♦

Squamous hyperplasia is any nonatypical thickening of the epithelia covering the glans, coronal sulcus, or foreskin

♦

Rather than a specific entity, it is usually part of various forms of penile dermatosis, especially lichen sclerosus

♦

Squamous hyperplasia is frequently associated with differentiated PeIN and low-grade variants of squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) such as usual, papillary, pseudohyperplastic, and verrucous carcinomas

Clinical

♦

Squamous hyperplasia is usually found in association with precancerous or invasive lesions

♦

A solitary presentation, without dermatosis or cancerous lesions, is infrequent

Macroscopic

♦

The typical aspect is that of whitish plaques with irregular borders. Sometimes a slightly raised and pearly appearance is observed

Microscopic

♦

Squamous hyperplasia is charact (Fig. 40.6A). Parakeratosis is usually absent and koilocytic changes are not seen. Not unusual is the concomitant presence of lichen sclerosus

Fig. 40.6.

Sq uamous hyperplasia. (A) There is epithelial thickening with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis but with preserved maturation and no cytological atypias. The base of the lesion is flat. Note the globular stromal hyalinization typical of early lichen sclerosus. (B) Verrucous hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, granulosis, acanthosis, and a broad base. (C) At high-power hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis and lack of atypias are noted.

♦

Four patterns of growth can be identified: (a) Flat: The interface between the epithelium and the stroma is linear; this is the most common subtype. (b) Papillary: There are hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis with no atypias (Fig. 40.6B). (c) Pseudoepitheliomatous: downward proliferation of epithelial rete ridges that appear detached from the overlying acanthotic epithelium; the epithelial nests are regular with no evident stromal reaction. (d) Verrucous or verrucoid: prominent acanthosis with hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and slight papillomatosis; it is commonly found adjacent to verrucous carcinomas (Fig. 40.6B, C)

♦

Lichen sclerosus is present in the majority of cases of squamous hyperplasia

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Differentiated PeIN. The presence of cytological atypia, even minimal, and altered epithelial maturation should prompt the diagnosis of PeIN; parakeratosis, a rare finding in squamous hyperplasia, is usually found in these cases. Positivity for p53 and Ki-67 above the basal layer would favor differentiated PeIN

♦

Pseudohyperplastic SCC can be confused with squamous hyperplasia, especially with the pseudoepitheliomatous pattern. However, epithelial nests in pseudohyperplastic SCC are more irregular, peripheral palisading is not evident, there is usually a marked stroma reaction, and, although minimal, there is cytological atypia

♦

Distinguishing verrucous carcinoma from verrucoid squamous hyperplasia can sometimes be difficult, especially in small biopsies. The presence of cytological atypia and stromal reaction are indicative of a neoplastic process. The clinical aspect of the lesion can aid in problematic case s

Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PeIN)

General Features

♦

Any degree of cytological atypia and altered epithelial maturation in the squamous epithelium lining the glans, coronal sulcus, or foreskin. The cytological alterations can be subtle or can occupy most or the entire epithelial thickness. In all cases, no evidence of extension beyond the basal lamina is observed

♦

PeIN is classified into differentiated (“simplex”) and undifferentiated, the latter subclassified in warty, basaloid, and warty–basaloid types. There are cases of mixed differentiated–undifferentiated PeIN in the same specimen. Less frequent patterns are clear cell, pagetoid, and pleomorphic, among others (Table 40.2)

Table 40.2.

P eIN Subtypes

PeIN Classification |

|---|

1. Differentiated PeIN |

2. Undifferentiated PeIN Basaloid Warty Warty–basaloid |

3. Mixed Differentiated+undifferentiated |

4. Others Pagetoid Clear cell Undete rmined |

♦

Differentiated PeIN are usually negative for HPV whereas undifferentiated PeIN are frequently associated with the virus

Clinical

♦

PeIN is frequently found in association with penile carcinomas, either merging with the invasive component or adjacent to it. However, PeIN can also be detected as a single lesion during clinical examination for other conditions or during peniscopy

♦

Differentiated PeIN preferentially occurs in the foreskin of older individuals, but the glans is also affected

♦

Undifferentiated PeIN involves preferentially the glans of patients younger than those with differentiated PeIN

Macroscopic

♦

Differentiated PeIN presents as a single whitish macula, plaque, or slightly raised geographical lesion. When associated with a penile carcinoma, it is usually found at the periphery of the tumor or in adjacent areas

♦

The gross appearance of warty or basaloid PeIN presenting as a single lesion is more variegated, with whitish, brownish, black-pigmented, or erythematous maculae, plaques, or papules with a granular or velvety surface

Microscopic

♦

Differentiated PeIN is characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and elongated rete ridges associated with altered epithelial maturation and more or less extended epithelial atypia (Fig. 40.7A, B). Nuclear pleomorphism, coarse chromatin, and evident nucleolus are cytological features usually found in the epithelial cells. The atypical changes can be limited to the lower one-third of the epithelium or extend through most or all of it. Differentiated PeIN is also frequently found in association with lichen sclerosu s (Fig. 40.7A–D)

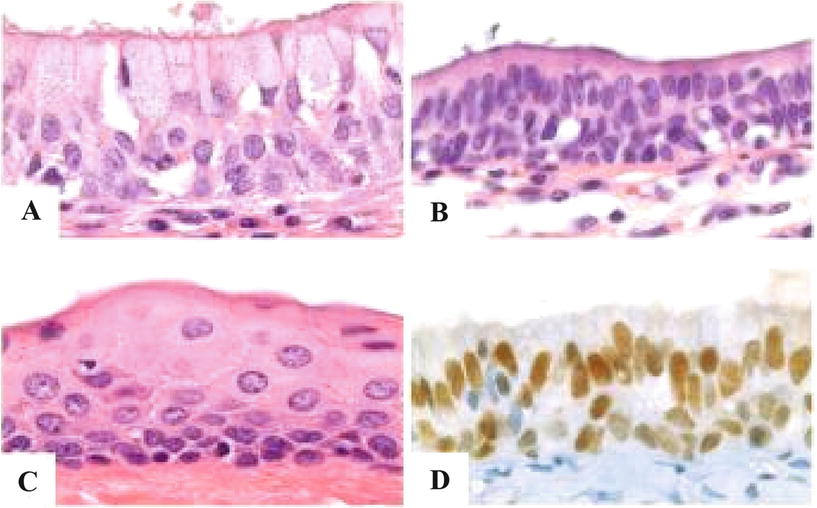

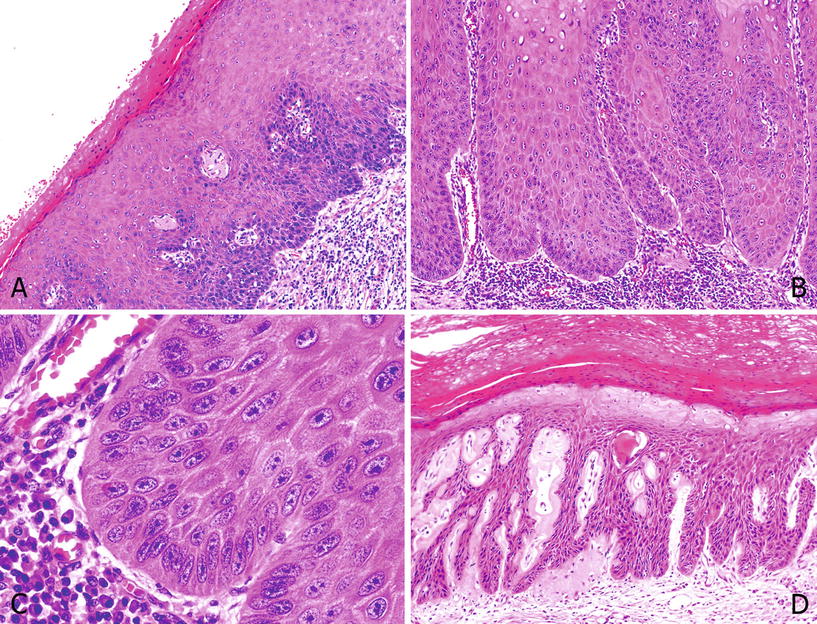

Fig. 40.7.

D ifferentiated PeIN. (A) Differentiated PeIN: hyper and parakeratosis and epithelial thickening. Squamous maturation is noted, with mild atypical cells in the basal layers. Note perivascular and globular hyalinization of lichen sclerosus in superficial lamina propria. (B) Acanthosis and squamous cell maturation. Atypical cells involve more than a third of the epithelial thickness. (C) At higher-power cells, basal layer cells show marked atypias with prominent nucleoli. (D) There are squamous cell atypias throughout the epithelium. There is an associated lichen sclerosus with dense stromal hyalinization.

♦

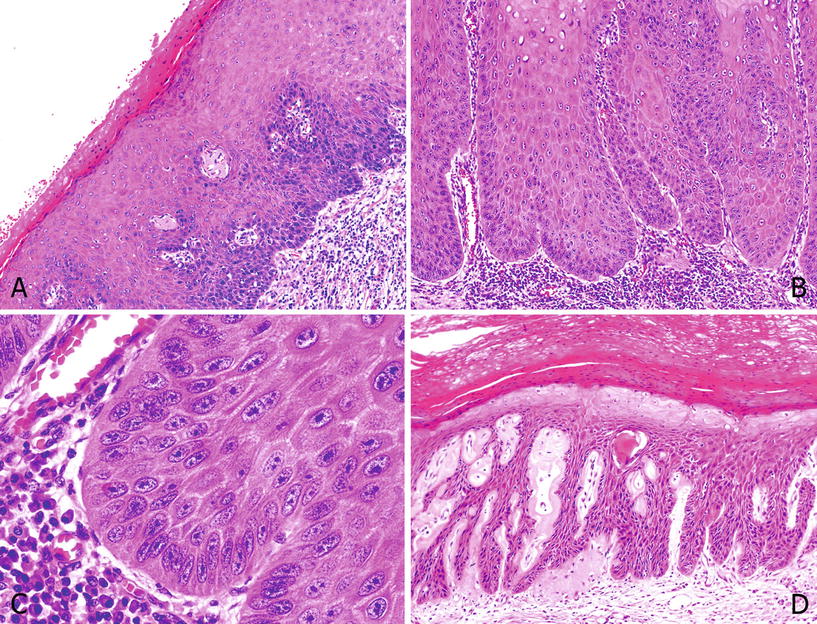

In basaloid PeIN, the epithelium is replaced by a monotonous proliferation of blue cells of small to intermediate size with scant basophilic cytoplasm. Apoptosis and a high mitotic rate are common findings. Parakeratosis and isolated koilocytes are seen in some cases. A papillary pattern of growth is unusual and in most of the cases the surface is flat. p16 is positive in most cases (Fig. 40.8A–D)

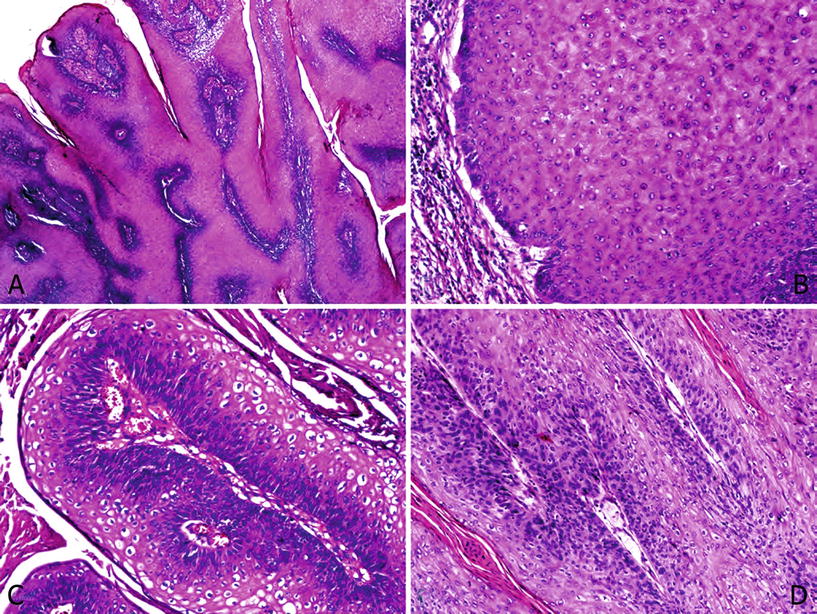

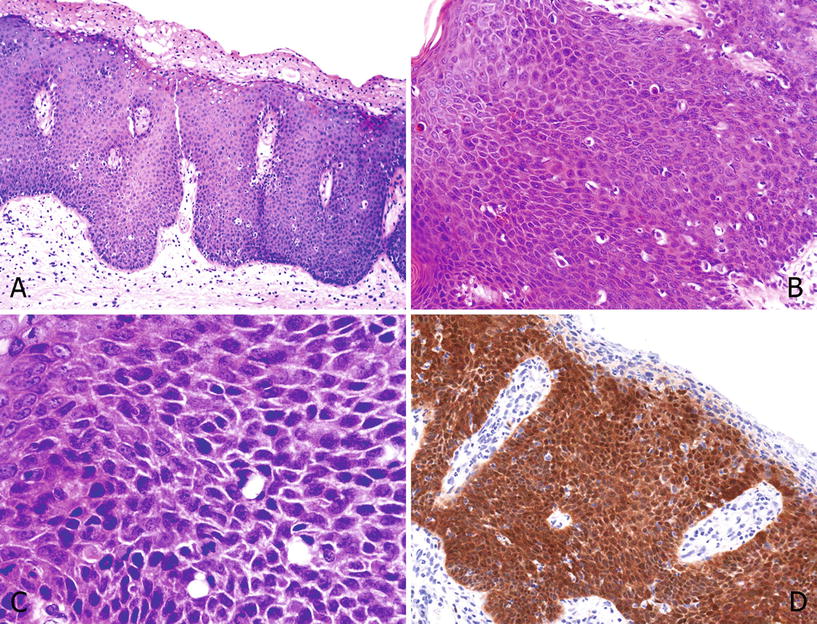

Fig. 40.8.

Undiffere ntiated PeIN, basaloid. (A) Surface parakeratosis and full epithelial thickness with small atypical basophilic cells. Note the apoptotic cells. The base is flat to rounded. (B) Atypical basaloid cells with a starry sky appearance due to individual cell necrosis. Mitotic figures are present. (C) At high-power nuclei are anaplastic with scant cytoplasm and inconspicuous nucleoli. (D) p16 is positive except in the parakeratotic layer.

♦

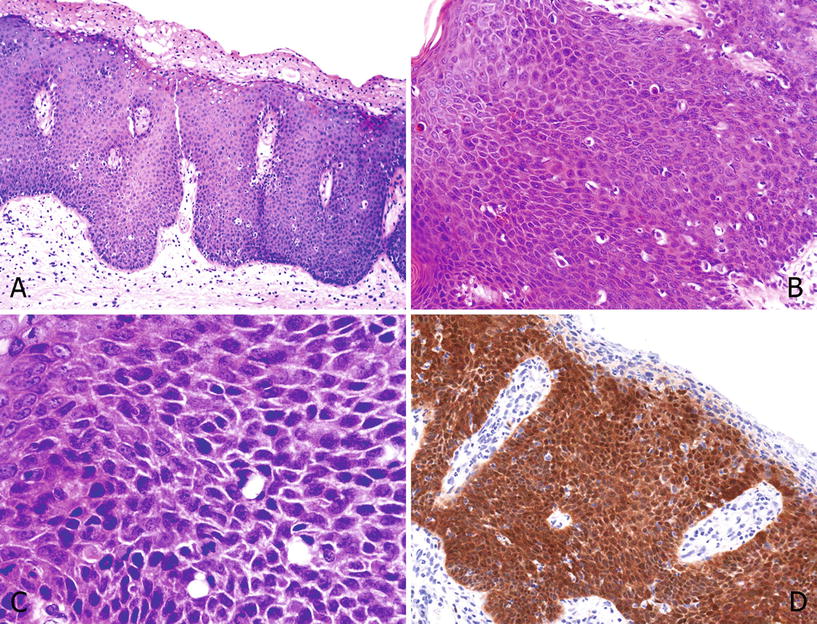

In warty PeIN the surface shows a characteristic spiky aspect, with conspicuous koilocytosis and atypical parakeratosis. Cellular pleomorphism is more evident than in basaloid PeIN. p16 is positive in most cases (Fig. 40.9A–D)

Fig. 40.9.

Undifferen tiated PeIN, warty. (A) Hyper and parakeratosis, micropapillomatosis, and cell maturation with pleomorphism. Scattered clear cell koilocytes are noted. (B) Condylomatous papillae with parakeratosis, koilocytosis, and a central fibrovascular core. (C) High power showing parakeratosis and pleomorphic koilocytosis with clear cell features. (D) p16 is positive except in the parakeratotic areas.

♦

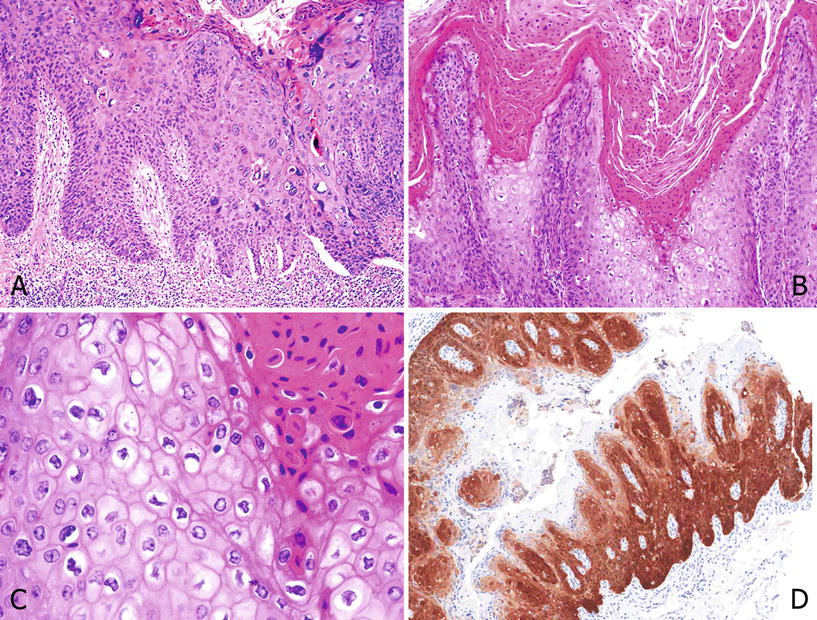

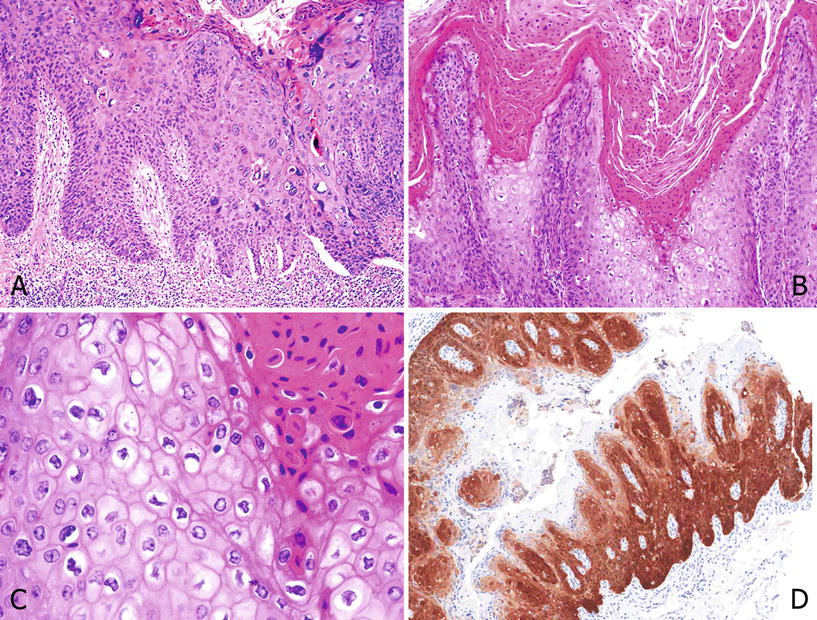

In some cases, a mixed warty–basaloid PeIN is observed. Both components can be found in different adjacent areas of the same lesion or can be a superimposed pattern in which the upper third of the epithelium shows warty features, while the lower half is basaloid. p16 is positive in most cases (Fig. 40.10A–D)

Fig. 40.10.

Undifferen tiated PeIN, warty–basaloid. (A) Upper third with clear cell warty and lower half with basaloid features. (B) Papillomatous lesions with surface warty and basal basaloid cells. (C) A closer view showing marked parakeratosis, clear warty cells, and small anaplastic basaloid cells. (D) p16 is positive especially in the basaloid cell component of this mixed lesion.

♦

A mixed differentiated, warty, and/or basaloid PeIN is also occasionally observed

♦

Differentiated PeIN tend to be associated with non-HPV-related keratinizing variants of penile carcinoma such as usual, papillary, and verrucous SCC, while PeIN with warty and/or basaloid features is mostly found with HPV-related tumors such as warty and basaloid carcinomas

♦

p16 is positive in warty and basaloid PeIN and negative in differentiated PeIN

♦

The immunohistochemical profile of PeIN is shown in Table 40.3

Table 40.3.

PeIN Immunohistochemical Profile

PeIN subtype | p16 | p53 | Ki–67 |

|---|---|---|---|

Differentiated | – | +/− | + |

Undifferentiated | + | +/− | + |

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Differentiated PeIN should be distinguished from squamous hyperplasia (see above )

♦

Basaloid PeIN should be distinguished from urothelial carcinoma in situ of the distal urethra. Immunohistochemical urothelial markers, such as uroplakin-III, GATA 3, thrombomodulin, and cytokeratins 7 and 20, are helpful in difficult cases. Overexpression of p16INK4a is characteristic of basaloid PeIN and absent in urothelial carcinomas

♦

Warty PeIN can be confused with condyloma acuminatum. The presence of cytological atypias and the identification of high-risk HPV (16 and 18) are indicative of PeIN. Overexpression of p16INK4a, consistently absent in condylomata, can also be helpfu l

Lichen Sclerosus

General Features

♦

Also known as “balanitis xerotica obliterans,” lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory and sclerotic condition affecting mainly the penis and vulva. Its frequent association with differentiated PeIN and with special variants of SCC, especially those non-HPV-related, strongly suggests a precancerous role

♦

The etiology is unknown, but several conditions, such as autoimmune diseases and immunologic dysregulations, are associated with this disease. HLA haplotypes, especially DQ7 but also DR7, DQ8, DQ9, and DR4, are frequently present in patients with lichen sclerosus

Clinical

♦

Lichen sclerosus has a predilection for the foreskin and the glans and is frequently found in cases of phimosis. It can extend to penile suburethral lamina propria

Macroscopic

♦

The typical aspect is that of irregular whitish atrophic areas located in the foreskin or in the perimeatal area of the glans. The presence of at least some degree of phimosis is not uncommon. In more advanced cases, the extensive sclerosis produces a marked narrowing of the preputial ring. Concurrent areas of squamous hyperplasia, differentiated PeIN, or even invasive SCC can be found

♦

Lichen sclerosus is frequently multicentric and may affect multiple anatomical compartments

Microscopic

♦

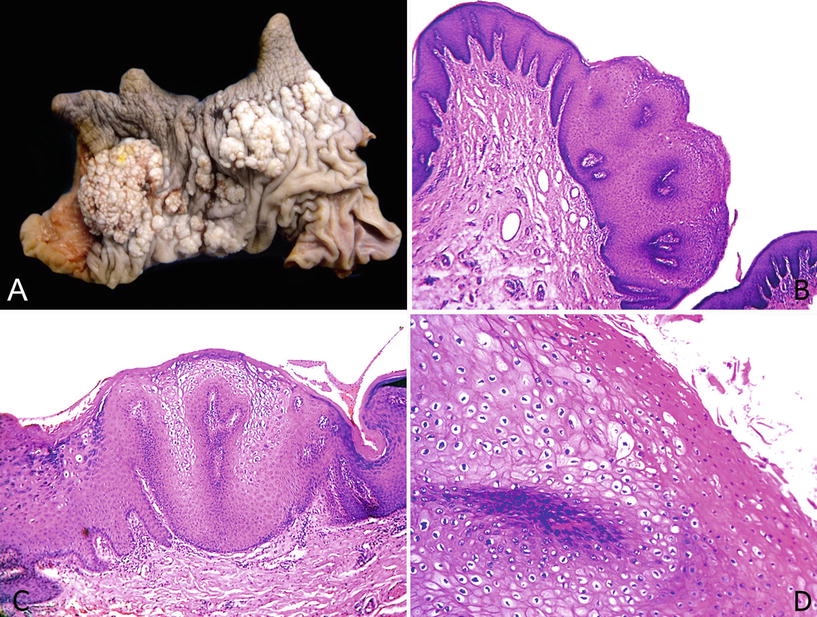

The disease affects all tissue anatomical layers. A topographical evaluation of the various penile tissue layers typically involved by lichen is helpful (Fig. 40.11A–F): squamous epithelium, epithelial–stromal interface or basal layer, superficial lamina propria, deep lamina propria, and dartos or corpus spongiosum

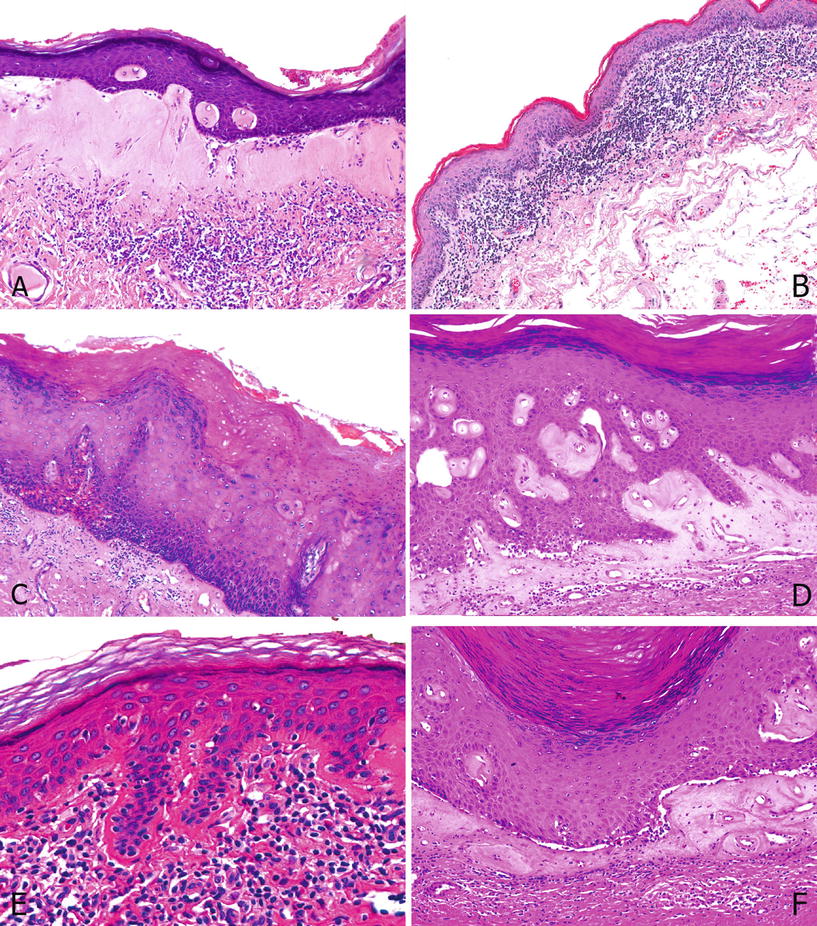

Fig. 40.11.

Lich en Sclerosus. (A) Classical lichen with a deeply located band of lymphocytic infiltration separated by a sclerotic band. (B) Lichenoid lichen with dense lymphocytic infiltration at the epithelial stromal junction. There is also atrophy: decreased in the number of squamous cell layers, normally about 10–12 cell layers. (C) Undetermined lichen: There is dermal fibrosis with scanty lymphocytic infiltration. Note the differentiated PeIN overlying the lesion. (D) Dense sclerosis in papillary dermis with perivascular and globular hyalinization. Also note the basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction with cells showing vacuolar degenerative changes, typical of lichen sclerosus. (E) Linear hyalinization: Dense hyalinization is present along the basement membrane. (F) Note the separation artifact.

♦

Epithelium is either hyperplastic (more common) or atrophic. There is hyper or parakeratosis

♦

There is ulceration and secondary inflammation

♦

The basal layer at the interface shows a vacuolar degeneration

♦

Epithelium is separated from lamina propria

♦

Superficial lamina propria shows characteristic perivascular, globular, or linear hyalinization

♦

Deeper lamina propria shows edema or sclerosis with hypervascularity in some cases

♦

Dartos or superficial corpus spongiosum can be similarly affected by the sclerotic process

♦

A lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate is variable in topography or density

♦

A dense lymphocytic infiltrate is present at the stromal–epithelial junction (lichenoid variant)

♦

A sparse lymphocytic infiltrate is present in lamina propria, especially in patients with cancerous lesions

♦

A dense lymphocytic infiltrate is present in deep lamina propria or dartos beneath the sclerosis in classical lichen sclerosus

♦

If the squamous epithelium associated with lichen sclerosus is atypical, the term “differentiated PeIN” should be use d

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous hyperplasia shows no sclerosis and no basal vacuolization. Sclerosis may be subtle and lymphocytic infiltrate minimal. Look for perivascular, globular, or lineal hyalinization which can be focal but when present is diagnostic of lichen sclerosus

♦

Differentiated PeIN. Minimal atypias found in cases of lichen sclerosus are sufficient for the diagnosis of differentiated PeI N

Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Variants

General Features Epidemiology

♦

Penile cancer is rare in certain geographical regions , such as the USA, Europe, Israel, and Japan but highly prevalent in others, especially South America, Africa, and some regions of Asia. Highest age-standardized rates (ASR) are from Paraguay, Brazil, Uganda, and Thailand

♦

The majority of patients are in the fifth to sixth decades of age. The disease is occasionally seen in young adults but is exceedingly rare in children

♦

There is a bimodal pathway in penile carcinogenesis, HPV related and non-HPV-related

♦

HPV is etiologically related with about half of penile carcinomas

♦

There are special subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma usually associated with HPV: basaloid, warty, warty–basaloid, the papillary variant of basaloid carcinomas (see below), clear cell and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. The distribution is shown in Table 40.4

Table 40.4.

Variants of SCC According to HPV Presence

A. HPV unrelated | B. HPV related | C. Others |

|---|---|---|

1. Usual | 1. Basaloid | 1. Mixed |

2. Verrucous | 2. Warty | 2. Unclassified |

3. Papillary, NOS | 3. Warty–basaloid | |

4. Cuniculatum | 4. Papillary basaloid | |

5. Pseudoglandular | 5. Clear cell | |

6. Pseudohyperplastic | 6. Lymphoepithelioma-like | |

7. Adenosquamous | ||

8. Sarcomatoid |

♦

HPV 16 is the most commonly found genotype in penile carcinomas. The distribution is shown in Table 40.5

Table 40.5.

Histological Subtypes of Penile SCC and HPV Genotypes in Single or Multiple Infections

Subtypes | 6 | 11 | 16 | 18 | 33 | 35 | 39 | 45 | 52 | 56 | 59 | 68/73 | 70 | 74 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Basaloid | 1 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Warty–basaloid | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Warty | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Usual | 1 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Mixed | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Papillary | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Total | 5 | 3 | 45 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

♦

Subtypes of carcinomas not related with HPV are usually associated with penile lichen sclerosus. They are usual; verrucous; papillary, NOS; cuniculatum; pseudohyperplastic; and sarcomatoid carcinomas

Risk Factors

♦

Phimosis, defined as a difficulty or impossibility of retracting the foreskin beyond the glans corona, is frequently present in patients with invasive penile cancer (Fig. 40.12). It may result from chronic balanitis, lichen sclerosus, or other systemic conditions. The protective effect of circumcision at birth may be related to the prevention of phimosis

Fig. 40.12.

Phimosis. Cut surface of a partial penectomy specimen showing complete obliteration of the preputial orifice due to severe phimosis. The glans and the tumor are concealed.

♦

Cigarette smoking has been linked to penile cancer, and several epidemiological studies have established a dose–response relation, with heavy smokers at higher risk

♦

The presence of lichen sclerosus is significantly associated with some special subtypes of HPV-unrelated penile carcinomas such as usual, pseudohyperplastic, verrucous, and papillary SCC s, especially when located exclusively in the foreskin. Almost 10% of patients with long-standing lichen sclerosus will develop a penile carcinoma

♦

Other risk factors are antecedents of penile tears, abrasions, injuries, chronic balanitis, genital warts, immunosuppression, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, treatment with psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA), and radiation therapy lichen planus

Strategies for Cancer Prevention

♦

Circumcised patients are at much lower risk for presenting invasive penile cancer, especially when circumcision is practiced at birth

♦

A better penile hygiene can reduce the risk for penile cancer by reducing the incidence of chronic balanitis and the subsequent development of phimosis. Smegma is not considered carcinogenic per se although its presence is an indicator of poor penile hygiene

♦

Since high-risk HPVs 16 and 18 are present in about one-half of penile carcinomas, vaccination in males has a potential for prevention

Pathological Features

♦

Most penile carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas originating in the epithelial lining covering the glans, coronal sulcus, or foreskin. The glans is the preferred site of origin (80%) followed by the foreskin (15%) and coronal sulcus (5%) (Fig. 40.13). Carcinomas originating in the skin of the shaft or the preputial outer skin are exceedingly rare

Fig. 40.13.

Carcinom a of the coronal sulcus. There is an irregular invasive white-gray tumor mass involving preferentially the coronal sulcus.

♦

Most penile cancers are squamous cell carcinomas of the usual type, morphologically similar to those of other sites, especially vulva. The remainders are classified as special variants. Each one of these subtypes presents particular clinicopathological features associated with a specific biological behavior

♦

In geographical areas of high incidence, up to half of the tumors are bulky and affect more than one anatomical compartment. Site of origin in these cases are difficult to establish

♦

Tumors located exclusively at the glans are usually of higher histological grade, more clinically aggressive, associated with PeIN showing warty and/or basaloid features, and HPV related in a significant proportion of cases. Tumors exclusive of the foreskin are usually well-differentiated keratinizing carcinomas, frequently associated with differentiated PeIN and lichen sclerosus, mostly non-HPV-related and of better prognosis

Patterns of Growth

♦

Four macroscopic patterns of growth are recognized: superficial spreading, vertical growth, verruciform, and multicentric

♦

Superficial spreading: Low-grade flat tumor with extension up to lamina propria or superficial corpus spongiosum, usually affecting more than one anatomical compartment with a horizontal pattern of growth. It is observed in about one-third of the cases. An extensive PeIN component may be observed

♦

Vertical growth: High-grade deeply infiltrative tumor with an ulcerated surface, usually affecting only one anatomical compartment, with a high rate of nodal metastases. Foci of necrosis and hemorrhage are common. Basaloid, sarcomatoid, and high-grade usual SCC usually present this pattern of growth

♦

Verruciform: Exophytic and usually bulky low-grade tumors with a low rate of regional metastases despite their large size. The preferred anatomical site is the glans, but the foreskin and, infrequently, the coronal sulcus can also be involved. They include verrucous, warty (condylomatous), papillary, and cuniculatum carcinomas. Giant condylomata can also present a similar pattern of growth. Differential features are shown in Table 40.1

♦

Multicentric: Two or more anatomically unconnected foci of carcinoma, with a tendency to affect multiple compartments. The epithelia between the malignant areas can be normal or hyperplastic. Multicentricity is common in some special SCC variants such as pseudohyperplastic carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree