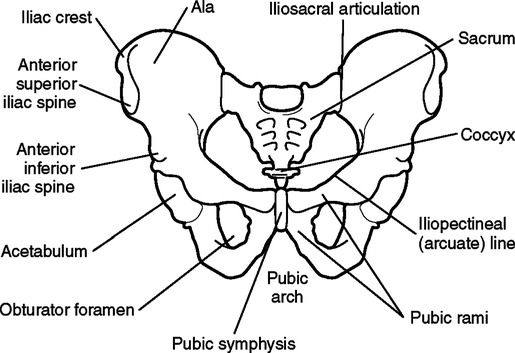

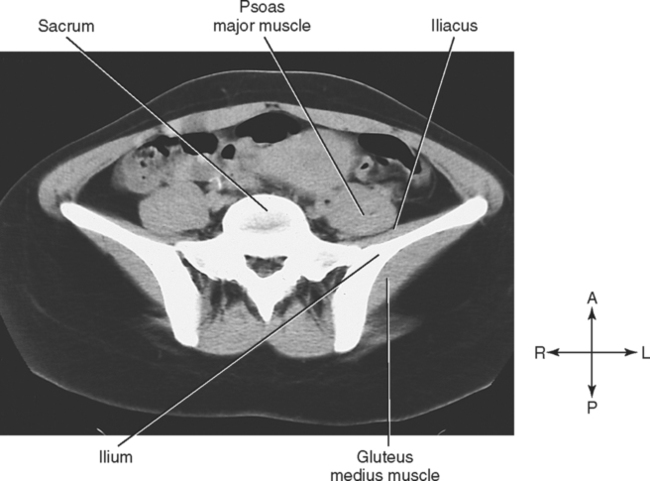

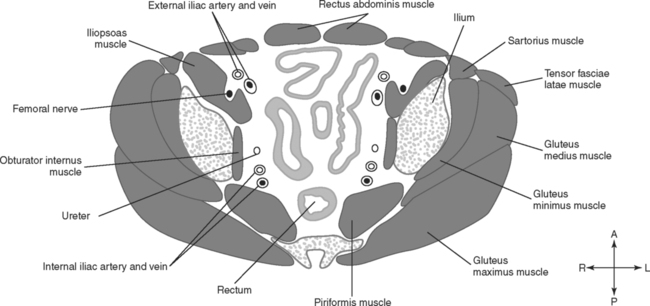

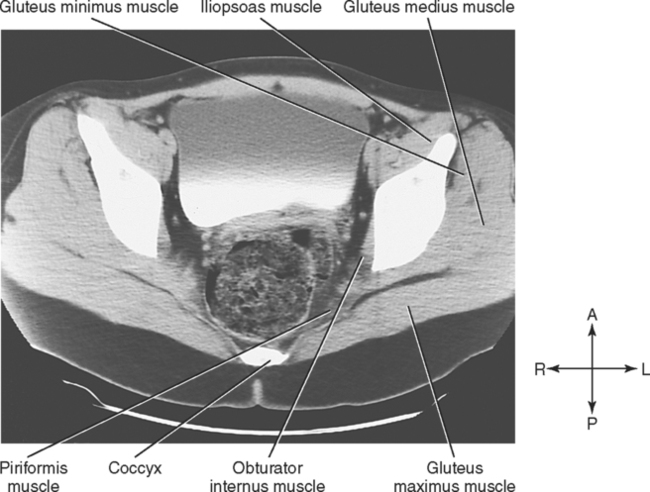

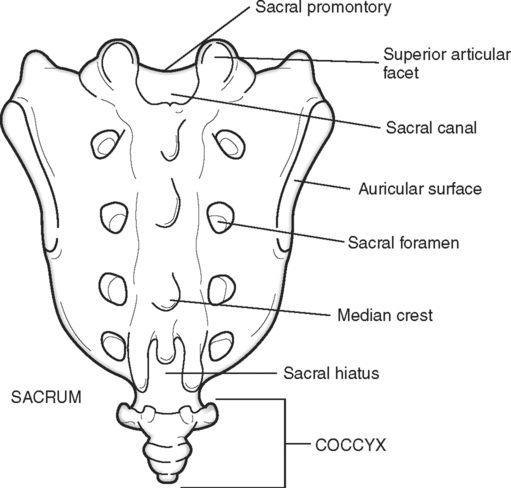

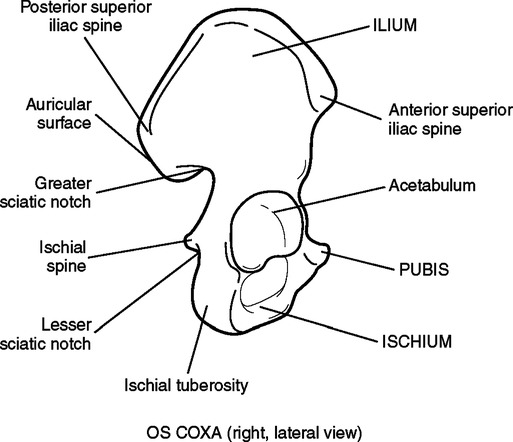

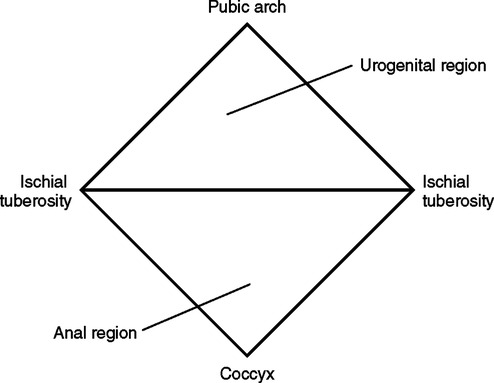

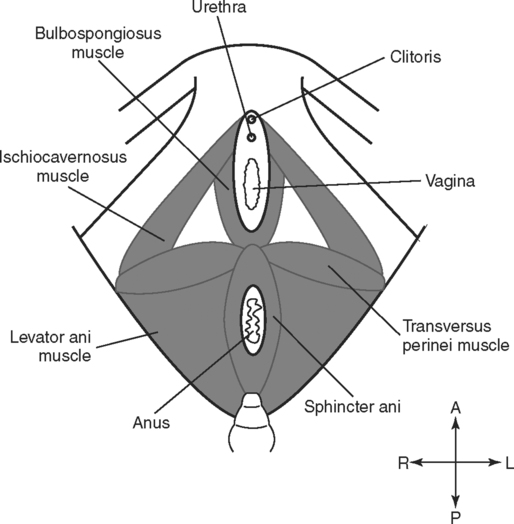

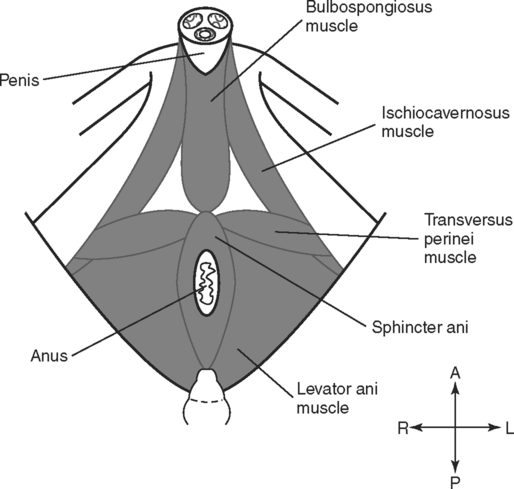

Upon completion of this chapter, the student should be able to do the following: • Differentiate between the greater, or false, pelvis and the lesser, or true, pelvis. • Describe the features of the sacrum and coccyx. • Name the three bones that form the os coxa and describe the features of the os coxa. • Compare the structure of the os coxa in the child and in the adult. • Identify the two principal muscles that line the wall of the true pelvis. • Describe the structures that support the pelvic viscera and prevent them from falling through the pelvic outlet. • Identify and compare the three muscles in the urogenital region of the perineum in the male and in the female. • Describe the vascular supply to the pelvis. • Name two nerves that emerge from the sacral plexus and state the importance of each. • Describe the anterior relationships of the rectum both in the male and in the female. • Compare the relationships of the urinary organs both in the male and in the female. • Describe the normal location and attachments of the ovaries and factors that may alter the location. • Identify the largest ligament that supports the uterus and name three smaller supporting ligaments. • Describe the normal position and relationships of the uterus. • Describe the relationships of the fornix of the vagina to the cervix. • Describe the structure and location of the testes and the epididymis. • Describe the structure of the scrotum and the spermatic cord. • Identify three accessory glands of the male reproductive system and describe the location of each gland. • Discuss the relationships of the seminal vesicles and prostate glands. • Compare the dorsal and ventral columns of erectile tissue in the body and the root of the penis. • Compare vessel and muscle relationships in transverse sections through the sacroiliac joint and in transverse sections through the lower part of the sacrum. • Distinguish between the rectovesical pouch, the vesicouterine pouch, and the rectouterine pouch. • Identify the muscles, viscera, blood vessels, and skeletal components of the female pelvis in transverse, sagittal, and coronal sections. • Identify the muscles, viscera, and blood vessels, as well as skeletal components, of the male pelvis in transverse, sagittal, and coronal sections. The sacrum and the coccyx (Fig. 4-1) make up the posterior midline portion of the bony pelvis. The sacrum transmits the weight of the body to the hip bones and then to the lower extremities. Normally, five sacral vertebrae fuse into one triangular mass, called the sacrum, that articulates with the fifth lumbar vertebra superiorly, the coccyx inferiorly, and the os coxae laterally. Where the sacrum meets the fifth lumbar vertebra, the sacrum is tilted posteriorly to form a lumbosacral angle. In some individuals the first sacral vertebra remains separate from the other four, or the fifth lumbar vertebra may fuse with the sacrum. Both conditions put a strain on the nearest intervertebral articulation, which may result in joint degeneration and cause low back pain. The os coxae (innominate bones) are commonly called the hip bones. Each os coxa consists of an ilium, a pubis, and an ischium. In the child these are three separate bones joined together by hyaline cartilage, and each bone has its own ossification center in the cartilage. Ossification continues during childhood until the cartilage is replaced by bone. By puberty, only a small amount of cartilage remains as a Y-shaped region where the three bones meet in the acetabulum. When ossification is complete, the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis are fused together to form a single unit, called the os coxa (Fig. 4-2). The ilium, ischium, and pubis meet in the acetabulum, which is a deep fossa for articulation with the head of the femur. The three bones also surround an opening called the obturator foramen, which is directed inferiorly. This foramen is closed by the obturator membrane and muscles. The pelvic outlet (inferior pelvic aperture) must also be covered to give support and maintain the pelvic viscera in position. The features of the os coxa are summarized in Table 4-1; see Fig. 4-2 and Fig. 4-3 to identify the features. TABLE 4-1 Important Markings on the Coxal Bones Functionally, the muscles of the pelvic wall are associated with movements of the thigh. Other muscles, such as the gluteal muscles and the anterior thigh muscles, are external to the pelvis but are seen in pelvic sections. These muscles are mentioned here and described in greater detail with the lower extremity. Table 4-2 summarizes the pelvic muscles. TABLE 4-2 The muscles in the wall of the greater, or false, pelvis are actually abdominal muscles. The two principal muscles, the psoas major muscle and the iliacus muscle, extend throughout the whole pelvic region and continue into the anterior thigh. The computed tomography (CT) image in Fig. 4-4 illustrates these two muscles in a transverse plane. Most of the inner surface of the bony true pelvis is lined with muscle. The obturator internus and piriformis muscles are the principal muscles that make up the wall of the true pelvis and form this lining. The line drawing in Fig. 4-5 illustrates the two muscles, and Fig. 4-6 is a CT image of these muscles. External to the pelvic and urogenital diaphragms are the muscles of the perineum. The outline of this region is roughly diamond shaped (Fig. 4-7). Anteriorly to posteriorly, the region extends from the pubic arch to the tip of the coccyx. The two ischial tuberosities form the two lateral points. A line drawn between the ischial tuberosities divides the perineum into two regions: a posterior anal region and an anterior urogenital region. The arrangement of the muscles in the anal region is the same in both sexes; however, the muscles in the urogenital region are arranged differently in the male and female. The muscles found in the anal region are the levator ani and the sphincter ani. The levator ani muscle has been described previously as a primary muscle of the pelvic diaphragm. The sphincter ani muscle is part of the urogenital diaphragm and surrounds the anal canal. The musculature of the urogenital region consists of the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and transversus perinei muscles. Fig. 4-8 illustrates the arrangement in the female, and Fig. 4-9 shows the arrangement in the male. The transversus perinei muscles are horizontal, arising on the ischial tuberosities and passing medially to insert on the central perineal tendon. In other words, they pass along the line that divides the perineum into the urogenital and anal regions. The ischiocavernosus muscles also arise on the ischial tuberosities but pass forward to insert on the pubic arch and the crus of the penis in the male or the clitoris in the female. The bulbospongiosus muscle is in the median line of the urogenital region. In the female, the two parts of this muscle are separated by the urethra and the vagina. In the male, the fibers of the two muscles unite in the midline and encircle the corpus spongiosum of the penis. Numerous muscles, such as the gluteal muscles and the thigh muscles, are external to the pelvis but are apparent in sections through the pelvis. These muscles are associated with the hip joint and movement of the lower extremity. Some of the more important and obvious extrapelvic muscles are named and described briefly in Table 4-3. They are discussed in more detail with the lower extremity. Some of these muscles are illustrated with the pelvic wall muscles in Fig. 4-5 and Fig. 4-6. TABLE 4-3

The Pelvis

Anatomical Review of the Pelvis

Osseous Components

Sacrum.

Os Coxae.

Marking

Description

Purpose

Acetabulum

Deep depression on lateral surface of coxal bone

Socket for articulation with head of femur (thigh bone)

Obturator foramen

Large opening between the pubis and ischium

Passageway for blood vessels, nerves, muscle tendons; largest foramen in the body

Ilium

Large flaring region that forms the major portion of the coxal bone

Alae (wings)

Large flared portions of the ilium

Large area for numerous muscle attachments; forms false pelvis

Iliac crest

Thickened superior margin of the ilium

Muscle attachment; forms prominence of hips

Anterior superior iliac spine

Blunt projection at anterior end of the iliac crest

Attachment for muscles of trunk, hip, thigh; can be easily palpated

Posterior superior iliac spine

Blunt projection at posterior end of the iliac crest

Attachment for muscles of trunk, hip, thigh

Anterior inferior iliac spine

Projection on ilium inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine

Attachment for muscles of trunk, hip, thigh

Posterior inferior iliac spine

Projection on ilium inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine

Attachment for muscles of trunk, hip, thigh

Greater sciatic notch

Deep indentation inferior to the posterior inferior iliac spine

Passageway for sciatic nerve and some muscle tendons

Iliac fossa

Slight concavity on medial surface of alae

Attachment for iliacus muscle

Auricular surface

Large, rough region at posterior margin of iliac fossa

Articulates with sacrum to form the sacroiliac joint

Iliopectineal (arcuate) line

Sharp curved line at inferior margin of iliac fossa

Attachment for muscles; marks the pelvic brim

Ischium

Lower, posterior portion of the coxal bone

Ischial spine

Projection near junction of ilium and ischium; projects into pelvic cavity

Attachment for a major ligament; distance between the two spines tells the size of the pelvic cavity

Ischial tuberosity

Large rough inferior portion of ischium

Muscle attachment; portion on which we sit; strongest part of the coxal bones

Lesser sciatic notch

Indentation below the ischial spine

Passageway for blood vessels and nerves

Pubis

Most anterior part of coxal bone

Pubic symphysis

Anterior midline where two pubic bones meet

Pubic rami

Armlike portions that project from the pubic symphysis

Form margins of the obturator foramen

Pubic arch

V-shaped arch inferior to the pubic symphysis formed by the inferior pubic rami

Broadens or narrows the dimensions of the true pelvis

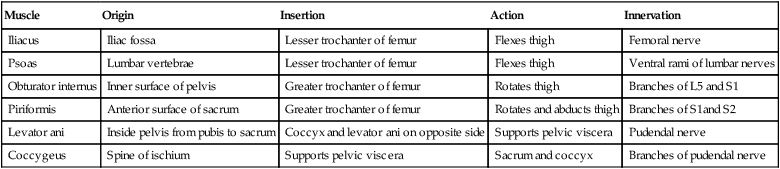

Muscular Components

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

Action

Innervation

Iliacus

Iliac fossa

Lesser trochanter of femur

Flexes thigh

Femoral nerve

Psoas

Lumbar vertebrae

Lesser trochanter of femur

Flexes thigh

Ventral rami of lumbar nerves

Obturator internus

Inner surface of pelvis

Greater trochanter of femur

Rotates thigh

Branches of L5 and S1

Piriformis

Anterior surface of sacrum

Greater trochanter of femur

Rotates and abducts thigh

Branches of S1and S2

Levator ani

Inside pelvis from pubis to sacrum

Coccyx and levator ani on opposite side

Supports pelvic viscera

Pudendal nerve

Coccygeus

Spine of ischium

Supports pelvic viscera

Sacrum and coccyx

Branches of pudendal nerve

Muscles in the Wall of the Greater (False) Pelvis.

Muscles in the Wall of the True Pelvis.

Muscles of the Pelvic Outlet.

Extrapelvic Muscles Seen in Pelvic Sections.

Muscle

Description

Gluteus maximus

The largest and most superficial muscle of the gluteal region; forms most of the mass of the buttocks

Gluteus medius

A thick, broad muscle of the gluteal region; located deep to the gluteus maximus but originating more superiorly, which results in the covering of the inferior one third by the gluteus maximus

Gluteus minimus

The smallest and deepest muscle of the gluteal region; underlies both the gluteus maximus and the gluteus medius

Gemelli

Two small muscle masses inferior to the piriformis muscle and deep to the lower part of the gluteus maximus; associated with the obturator internus tendon

Quadratus femoris

A short, flat, rectangular muscle that is located inferior to the gemelli and the extrapelvic portions of the obturator internus muscles

Tensor fasciae latae

A superficial muscle of the superior lateral thigh; overlies the superior lateral portion of the gluteus medius

Sartorius

A long, straplike muscle that courses obliquely and inferiorly across the anterior thigh; most superficial muscle of the anterior thigh

Rectus femoris

A large ropelike muscle mass that extends the length of the anterior thigh; one of the quadriceps femoris muscle group

Vastus lateralis

A large muscle that forms the lateral portion of the thigh; partially covered by the iliotibial fascia; one of the quadriceps femoris muscle group

Vastus medialis

A large muscle that forms the medial portion of the thigh; one of the quadriceps femoris muscle group

Vastus intermedius

An elongated muscle next to the shaft of the femur; deep to the rectus femoris, between the other two vastus muscles; one of the quadriceps femoris group

Pectineus

A flat muscle, medial to the iliopsoas, in the floor of the femoral triangle; apparent anterior to the pubic bone in transverse sections

Adductor longus

A superficial, flat muscle that extends obliquely from the pubis to the femur; medial to the pectineus

Adductor brevis

A flat muscle deep to the adductor longus on the medial aspect of the thigh

Adductor magnus

The largest of the adductor muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh; deep to the adductor longus and adductor brevis

Obturator externus

A relatively small, fan-shaped muscle that covers the obturator foramen; closely associated with the adductor muscles

Gracilis

A thin, straplike, superficial band of muscle that extends down the medial aspect of the thigh from the pubis to the tibia

Biceps femoris

A large, elongated muscle on the posterior and lateral aspects of the thigh; the superior portion is deep to the gluteus maximus; one of the hamstring muscles

Semitendinosus

A superficial muscle medial to the biceps femoris; the superior portion is deep to the gluteus maximus; one of the hamstring muscles

Semimembranosus

A fleshy muscle, deep and medial to the semitendinosus; one of the hamstring muscles

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine