Chapter 11 The nervous system

HIGHER CORTICAL FUNCTION

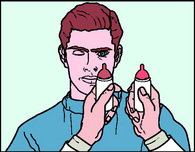

Examination (Fig. 11.1; Review Box p. 229)

Intelligence

Tests of knowledge and abstract thinking must take account of the patient’s social background.

ASSESSMENT OF DYSPHASIA

Fluency

Comprehension

Ask questions of increasing complexity, although still answerable by a yes or no response

PRAXIS

Primitive reflexes

A number of reflexes may emerge as the result of the disorders affecting higher cortical function.

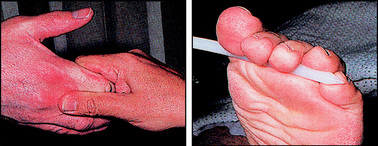

GLABELLAR TAP

Tap your index finger repetitively on the patient’s glabella. The blink response should inhibit after three to four taps. The response fails to inhibit in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

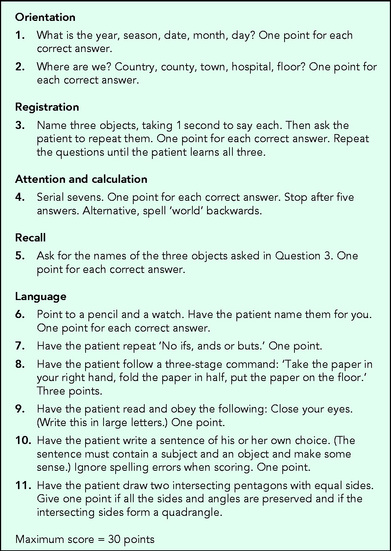

GRASP REFLEX

Elicited by stroking firmly across the palmar surface of the hand from the radial to the ulnar border. In a positive response, the examiner’s hand is gripped by the patient’s fingers, making release difficult or impossible. A foot grasp reflex is elicited by stroking the sole of the foot towards the toes with the handle of a patellar hammer. A positive response results in flexion of the toes with grasping of the hammer (Fig. 11.2).

Clinical application

AMNESIA

Damage to the limbic system leads to failure to learn new memories (antegrade amnesia) plus loss of memory for recent events (retrograde amnesia).

DYSARTHRIA

DYSPHONIA

Frequently non-organic. In spastic dysphonia, a form of dystonia, inappropriate muscle contraction, particularly of the larynx, produces strained and strangulated speech.

DYSPHASIA

AGRAPHIA

Nearly all aphasic patients have agraphia, but many patients with agraphia are not aphasic.

APRAXIA

PRIMITIVE REFLEXES

THE PSYCHIATRIC ASSESSMENT

Make sure that the patient understands who you are, and the purpose of the interview. Privacy is particularly important when sensitive issues are being explored. To begin with, avoid making notes, as this can detract from the relationship you are trying to establish with the patient. During this preliminary phase, observation of the patient’s posture, gestures and facial expression may provide information regarding mood and feeling. The depressed patient appears apathetic, has little expression and may well be reluctant to discuss the history. The agitated patient is restless.

Specific symptoms

MOOD

Enquire whether the patient, or a relative, has noticed any mood change. A particularly valuable question when screening for depression is whether the individual has lost pleasure in normal activities (anhedonia). Supplementary to this will be enquiries regarding sleep pattern, loss of libido and suicidal ideation. Sometimes the patient denies flattening of mood, when that is all too evident from the interview. Such discrepancies should be carefully recorded.

ABNORMAL THOUGHTS

Delusions

These are beliefs that can be demonstrated to be incorrect but to which the individual still adheres. Members of the Flat Earth Society are deluded. Often there is an element of reference, in other words that actions or words are directed specifically at that individual even if they appear on a global platform, for example television. Paranoid delusions contain a persecutory element. Delusions of worthlessness are particularly associated with depressive illness.

Symptoms and signs: Somatic and psychic symptoms of anxiety and depression

Symptoms and signs: Somatic and psychic symptoms of anxiety and depression

| Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Somatic | Palpitations | Altered appetite |

| Tremor | Constipation | |

| Breathlessness | Headache | |

| Dizziness | Bodily fatigue | |

| Fatigue | Tiredness | |

| Diarrhoea | ||

| Sweating | ||

| Psychic | Feelings of tension | Apathy |

| Irritability | Poor concentration | |

| Difficulty sleeping | Early-morning waking | |

| Fear | Diurnal mood swing | |

| Depersonalisation | Retardation | |

| Guilt |

ABNORMAL PERCEPTIONS

These are auditory or visual phenomena of which other individuals are not aware.

Hallucinations are experiences that have no objective equivalent to explain them. They are predominantly visual or auditory but can occur in other forms, for example, of smell or taste in patients with complex partial seizures. Visual hallucinations can be unformed, for example an ill-defined pattern of lights, or formed, the individual then describing people or animals, often of a frightening aspect. Visual hallucinations are more often a feature of an organic brain syndrome (e.g. delirium tremens or an adverse drug reaction) than a functional psychosis, e.g. schizophrenia. Auditory hallucinations are also either unformed or formed. They are found more often in the functional psychoses than in organic brain disease. The voices can take on a persecutory quality in schizophrenia and an accusatory element in depression. In déjà vu and jamais vu, intense feelings of a relived experience or a sensation of strangeness in familiar surroundings occur, respectively. Both can be a feature of everyday life but when pathological are usually epileptic. Illusions are misinterpretation of an external reality – all of us have this when watching a magician at work. In depersonalisation, the individual feels a detachment from the normal sense of self, in derealisation a detachment from the external world. Both occur in neurotic illnesses but also, periodically, in normal individuals.

The personal history

CHILDHOOD

It is unlikely that the patient will have accurate details of birth or early development unless there were particular problems with them. A direct question to the patient regarding whether he or she was happy or unhappy in childhood is useful. Some ‘happy’ responses turn out to be rather less so with further delving. If there is an expression of remembered unhappiness, explore it further in terms of relationships with parents and any physical illness.

PERSONALITY PROFILE

Evidence suggesting changing personality and mood is often better provided by colleagues, relatives or friends than by the patient. Questionnaires exist for the assessment of personality but even without them the patient’s attitude and behaviour, in terms of work and social relationships, personal ambitions, drive, level of independence and authority and response to stress, will indicate the patient’s maturity.

HEADACHE AND FACIAL PAIN

Headache

Often the history suffices to recognise the more serious causes. Factors to determine include:

THE CRANIAL NERVES

Second cranial nerve (optic)

EXAMINATION

Visual acuity

Visual fields

CLINICAL APPLICATION

Retinal vascular disease

Glaucoma

Symptoms and signs: Visual field defects

Symptoms and signs: Visual field defects

| Absolute central scotoma | Area around fixation in which there is no appreciation of the visual stimulus |

| Relative central scotoma | Area in which an object is detected but its colour is reduced (desaturated) |

| Centrocaecal scotoma | A field defect extending from fixation towards the blind spot |

| Bitemporal hemianopia | Involvement of the temporal halves of both fields |

| Homonymous hemianopia | Involvement of the temporal half of one field and the nasal half of the other |

Chiasmatic lesions

Typically due to a pituitary tumour, craniopharyngioma or meningioma. The resulting field defect is a bitemporal hemianopia, typically asymmetric.

Optic tract and lateral geniculate body lesions

Uncommon. Produce incongruous (i.e. non-matching) homonymous hemianopias.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Questions to ask: Assessment of dysphasia

Questions to ask: Assessment of dysphasia

Differential diagnosis: Disorders of higher cortical function and speech

Differential diagnosis: Disorders of higher cortical function and speech Review: Assessment of higher cortical function

Review: Assessment of higher cortical function Questions to ask: Psychiatric assessment

Questions to ask: Psychiatric assessment Differential diagnosis: Headache

Differential diagnosis: Headache Questions to ask: Facial pain

Questions to ask: Facial pain Symptoms and signs: Disturbances of olfaction

Symptoms and signs: Disturbances of olfaction