Table 11.1). The patient should be allowed to describe the symptoms in his or her own words to begin with, and then the clinician needs to ask questions to clarify information and obtain more detail. It is particularly important to ascertain the temporal course of the illness, as this may give important information about the underlying aetiology.

TABLE 11.1 Neurological history

| Presenting symptoms |

| Risk factors for cerebrovascular disease |

* Note particularly the temporal course of the illness, whether symptoms suggest focal or diffuse disease, and the likely level of involvement of the nervous system.

An acute onset of symptoms (within minutes to an hour) is suggestive of a vascular or convulsive problem (e.g. the explosive severe headache of subarachnoid haemorrhage or the rapid onset of a seizure).

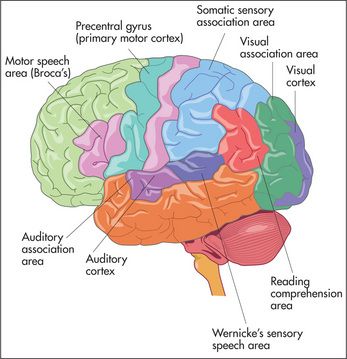

For these episodes of sudden onset, a precipitating event (e.g. exercise) or warning (aura) may be present. The aura that precedes a seizure may be localising (e.g. auditory hallucinations, an unusual smell or taste, loss of speech, or motor changes) or non-localising (e.g. a feeling of apprehension). The occurrence of an aura followed by sudden unconsciousness is very suggestive of the diagnosis of a major seizure or complex partial seizure.

A stroke or cerebrovascular accident usually causes symptoms which appear over minutes or are present when the patient wakes from sleep. There is a focal problem with function of the brain. Patients may be unable to move one side of the body (hemiplegia) or have difficulty with speech or swallowing, There may have been previous episodes. When there is resolution of the symptoms within 24 hours the episode is called a transient ischaemic attack—TIA). The rapid onset of focal symptoms almost always has a vascular cause—embolism, infarction or haemorrhage. If the patient can answer questions it is important to ask about the onset of the symptoms and about risk factors for stroke (

Questions box 11.1

The sudden onset of weakness on one side of the body followed by resolution and a severe headache is characteristic of hemiplegic migraine. Sudden resolution without headache suggests a transient ischaemic episode. The very gradual onset of muscle weakness suggests a muscle abnormality such as myopathy rather than a vascular event.

A subacute onset (hours to days) occurs with inflammatory disorders (e.g. meningitis, cerebral abscess or the Guillain-Barré

A more chronic symptom course suggests that the underlying disorder may be related to either a tumour (weeks to months) or a degenerative process (months to years). Metabolic or toxic disorders may present with any of these time courses.

Based on the history (and physical examination), a judgment is made as to whether the disease process is localised or diffuse, and which levels of the nervous system are involved (the nervous system may be thought of as having four different levels: the peripheral nervous system, the spinal cord, the posterior fossa, and the cerebral hemispheres). Consideration of the time course and the levels of involvement will usually lead to a logical differential diagnosis of the patient’s symptoms. After detailed questions about the presenting problem, ask about previous neurological symptoms and about previous neurological diagnoses or investigations. The patient may know the results of CT or magnetic resonance imaging brain scans performed in the past. A thorough neurological history will include routine questions about possible neurological symptoms (

Headache and facial pain

Headache is a very common symptom (

Questions box 11.3

Questions to ask the patient with headache

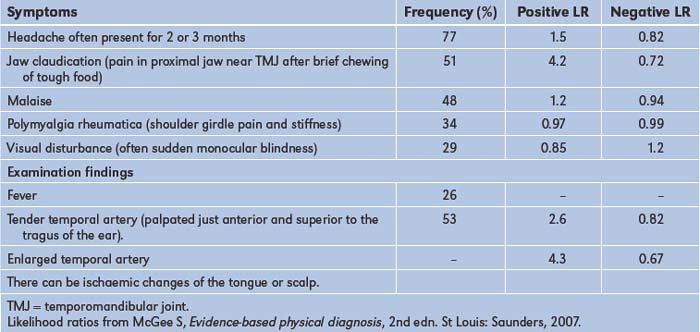

A generalised headache that is worse in the morning and is associated with drowsiness or vomiting may reflect raised intracranial pressure, while generalised headache associated with photophobia and fever as well as with a stiff neck of more gradual onset may be due to meningitis. A persistent unilateral headache over the temporal area associated with tenderness over the temporal artery and blurring of vision suggests temporal arteritis.

Finally, the most frequent type of headache is episodic or chronic tension-type headache; this is commonly bilateral, occurs over the frontal, occipital or temporal areas, and may be described as a sensation of tightness that lasts for hours and recurs often. There are usually no associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, weakness or paraesthesiae (tingling in the limbs), and the headache does not usually wake the patient at night from sleep.

Pain in the face can result from trigeminal neuralgia, temporomandibular arthritis, glaucoma, cluster headache, temporal arteritis, psychiatric disease, aneurysm of the internal carotid or posterior communicating artery, or the superior orbital fissure syndrome.

Faints and fits (see also

It is important to try to differentiate syncope (transient loss of consciousness) from epilepsy (

Questions box 11.4

Questions to ask the patient with syncope or dizziness

Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) affecting the brainstem can occasionally cause blackouts. Use of the term ‘drop attacks’ means the patient falls but there is no loss of consciousness. In either case the patient falls to the ground without premonition and the attacks are of brief duration. Hypoglycaemia can lead to episodes of loss of consciousness. Patients with hypoglycaemia may also report sweating, weakness and confusion before losing consciousness. Bizarre attacks of loss of consciousness occur with hysteria.

Dizziness

If a patient complains of dizziness, it is important to determine what is meant by this term. In true vertigo, there is actually a sense of motion, usually of the surroundings but also of the head itself (

Other causes of vertigo include:

Visual disturbances and deafness

Problems with vision can include double vision (diplopia), blurred vision (amblyopia), light intolerance (photophobia) and visual loss. The causes of deafness are summarised on

Disturbances of gait

Many neurological conditions can make walking difficult. These are described on

Disturbed sensation or weakness in the limbs

Pins and needles in the hands or feet may indicate nerve entrapment or a peripheral neuropathy (

Nerve root, spinal cord and cerebral abnormalities can all cause disturbance of sensation and weakness.

Limb weakness can be caused by lesions at different levels in the motor system. There are a number of patterns of limb and muscle weakness:

Tremor and involuntary movements

Tremor is a rhythmical movement (

| Parkinson’s disease | 3 to 5 Hz |

| Essential/familial | 4 to 7 Hz |

| Physiological | 8 to 13 Hz |

TABLE 11.4 Definitions of terms used to describe movement disorders

| Akithesia | Motor restlessness; constant semi-purposeful movements of the arms and legs |

| Asterixis | Sudden loss of muscle tone during sustained contraction of an outstretched limb |

| Athetosis | Writhing, slow sinuous movements, especially of the hands and wrists |

| Chorea | Jerky small rapid movements, often disguised by the patient with a purposeful final movement: e.g. the jerky upward arm movement is transformed into a voluntary movement to scratch the head |

| Dyskinesia | Purposeless and continuous movements, often of the face and mouth; often a result of treatment with major tranquillisers for psychotic illness |

| Dystonia | Sustained contractions of groups of agonist and antagonist muscles, usually in flexion or extremes of extension; it results in bizarre postures |

| Hemiballismus | An exaggerated form of chorea involving one side of the body: there are wild flinging movements which can injure the patient (or bystanders) |

| Myoclonic jerk | A brief muscle contraction which causes a sudden purposeless jerking of a limb |

| Myokymia | A repeated contraction of a small muscle group; often involves the orbicularis oculi muscles |

| Tic | A repetitive irresistible movement which is purposeful or semi-purposeful |

| Tremor | A rhythmical alternating movement |

Speech and mental status

Speech may be disturbed by many different neurological diseases and is discussed on

Past health

Inquire about a past history of meningitis or encephalitis, head or spinal injuries, a history of epilepsy or convulsions and any previous operations. Any past history of sexually transmitted disease (e.g. risk factors for HIV infection or syphilis) should be obtained. Ask about risk factors that may predispose to the development of cerebrovascular disease (

Medication history

Previous and current medications may be the cause of certain neurological or apparently neurological syndromes (

TABLE 11.5 Drugs and neurology

| 1 Anti-hypertensives |

| 2 Anti-platelet drugs and anti-coagulants |

| 3 Statins |

| 4 Major tranquillisers |

| 5 Other neurological symptoms associated with drugs |

Ask about treatment for neurological disorders with anticonvulsants, anti-Parkinsonian drugs, steroids, immunosuppressants, biological agents, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents and for other drug treatment that may be associated with neurological problems; use of the contraceptive pill, antihypertensive agents or drugs for other disorders needs to be documented.

Social history

As smoking predisposes to cerebrovascular disease, the smoking history is relevant. It is useful to ask about occupation and exposure to toxins (e.g. heavy metals). Alcohol can also result in a number of neurological diseases (see

Family history

Any history of neurological or mental disease should be documented. A number of important neurological conditions are inherited (

TABLE 11.6 Inherited neurological conditions

| X-linked | Colour blindness, Duchenne’s and Becker’s muscular dystrophy, Leber’s |

| Autosomal dominant | Huntington’s chorea, tuberose sclerosis, dystrophia myotonica |

| Autosomal recessive | Wilson’s disease, Refsum’s |

| Increased incidence in families | Alzheimer’s |

* Theodor Karl von Leber (1840–1917). German ophthalmologist, professor of ophthalmology at Heidelberg. He began studying chemistry but was advised by Bunsen that there were too many chemists and so changed to studying medicine.

† Siguald Refsum (1907–91), Norwegian neurologist. He described this in 1945, calling it heredotaxia hemerlopica polyneuritiformis. This may be an argument for the use of eponymous names.

‡ Warren Tay (1843–1927), English ophthalmologist, described the ophthalmological abnormalities of the condition. Bernard Sachs (1858–1944), American neurologist and psychiatrist, described the neurological features in 1187. He studied in Germany and was a pupil of von Recklinghausen. The condition was originally called amaurotic family idiocy. This may be another reason to use eponymous names.

§ Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), Bavarian neuropathologist, described the condition in 1906. His doctoral thesis was on the wax-producing glands of the ear.

The neurological examination

Examination anatomy

More than for any other system of the body, neurological diagnosis depends on localising the anatomical site of the lesion—in the brain, spinal cord or peripheral nerve.

As a preliminary to the neurological assessment, the clinician should obtain some biographical information from the patient, including the age, place of birth, handedness, occupation and level of education.

The examination of the nervous system and the interpretation of findings require a lot of practice. In a viva voce examination, this system more than any other system requires a polished technique. The signs need to be elicited carefully because the precise anatomical localisation of any lesions can often be determined this way. It is important, therefore, to remember some elementary neuroanatomy.

Examination can be long and difficult and it is said to take much of a day if absolutely everything that can be done (including psychometric assessment) is done. This is obviously impractical, but a screening examination that will uncover most signs takes only a relatively short time.

In brief, the following aspects of the examination must be attended to:

General signs

Consciousness

Note the level of consciousness. If the patient is unconscious look for responses to various stimuli (

Neck stiffness

Any patient with an acute neurological illness, or who is febrile or has altered mental status must be assessed for signs of meningism.

With the patient lying flat in bed, the examiner slips a hand under the occiput and gently flexes the neck passively (i.e. without assistance from the patient). The chin is brought up to approach the chest wall. Meningism may be caused by pyogenic or other infection of the meninges, or by blood in the subarachnoid space secondary to subarachnoid haemorrhage. There is resistance to neck flexion due to painful spasm of the extensor muscles of the neck. Other causes of resistance to neck flexion are characterised by an equal resistance to head rotation. They include: (i) cervical spondylosis; (ii) after cervical fusion; (iii) Parkinson’s disease; and (iv) raised intracranial pressure, especially if there is impending tonsillar herniation. The Brudzinski sign

Kernig’s sign

Although the diagnostic value has been questioned (combined meningeal signs had a positive LR of 0.92 and a negative LR of 0.88),

Handedness

Shake the patient’s hand and ask if he or she is right- or left-handed. This is polite and allows the examiner to assess the likely dominant hemisphere. Ninety-four per cent of right-handed people and about 50% of left-handed people have a dominant left hemisphere. There is division of function between the two hemispheres, the most obvious distinction being that the dominant hemisphere controls language and mathematical functions.

Orientation

Test orientation in person, place and time by asking the patient his or her name, present location and the date (normal patients who have been in hospital for long periods often get the day wrong as one day seems very much like another in hospital). Disorientation is not a specific localising sign and may be acute and reversible (delirium) or chronic and irreversible (dementia). The mini-mental state examination (

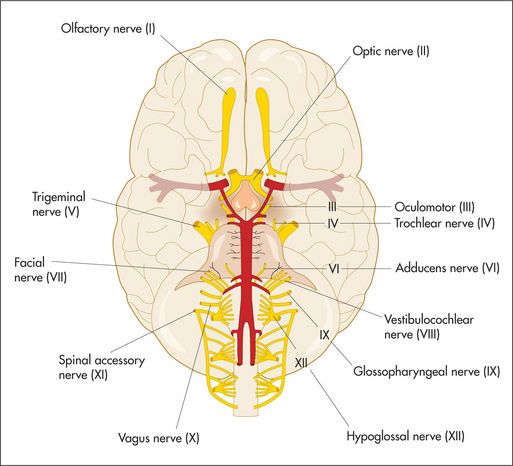

The cranial nerves

Examination anatomy

The cranial nerves (

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree