The Minimally Invasive Surgical Approach to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

W. Scott Melvin

Luke M. Funk

DEFINITION

▪ Endoscopic therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) include transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) and the application of radiofrequency energy to the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Minimally invasive LES augmentation surgery involves the placement of a magnetic band across the LES. All three therapies are designed to reduce GERD symptoms by minimizing the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and are alternatives to traditional surgical fundoplication techniques.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Typical GERD symptoms

Achalasia

Biliary colic/cholecystitis

Delayed gastric emptying

Esophageal cancer, esophagitis, esophageal motility disorders

Gastritis

Hiatal hernia

Helicobacter pylori infection

Irritable bowel syndrome

Atypical GERD symptoms

Coronary artery disease

Asthma

Bronchogenic carcinoma

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

History taking should focus on identifying both typical and atypical symptoms associated with GERD.

Typical symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, water brash (salty taste related to salivary secretion), and dysphagia.

Atypical symptoms include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, chest pain, recurrent pneumonias, hoarseness, and dental erosions.

Response to antireflux medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers is important to illicit, as the majority of patients with typical GERD symptoms will respond to these medications. Failure to respond to these medications should heighten the surgeon’s concern that the patient’s symptoms may be unrelated to GERD.

Once the diagnosis of GERD is confirmed with objective testing, several key points should be discussed with the patient:

Medical therapy, including lifestyle modifications (i.e., diet modification, weight loss, smoking cessation) and antireflux medications, should control typical GERD symptoms for most patients. Surgical intervention is indicated for GERD patients who (1) cannot take antireflux medications due to side effects, (2) would prefer not to take antireflux medications due to cost or lifestyle impact, or (3) continue to experience symptoms despite antireflux medications.

Laparoscopic gastric fundoplication (i.e., Nissen fundoplication) is considered to be the gold standard surgical therapy for the treatment of GERD. Endoscopic therapies and laparoscopic LES augmentation surgery should probably be reserved for GERD patients who are candidates for surgical intervention and (1) would prefer a less invasive option than laparoscopic fundoplication surgery or (2) would be considered too high risk for laparoscopic fundoplication due to comorbidities or previous abdominal surgery, including prior laparoscopic fundoplication.

Of the three procedures discussed in this chapter, laparoscopic LES augmentation surgery is the only one that requires general anesthesia, although TIF also involves general anesthesia in the vast majority of cases. Conscious sedation is usually adequate for radiofrequency therapy. Thus, poor candidates for general anesthesia (i.e., those with cardiopulmonary conditions such as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] or congestive heart failure [CHF]) may be better candidates for radiofrequency therapy. The presence of these comorbid conditions should be sought out in the history. Additional contraindications for these procedures are listed in Table 1.

Because there are few physical exam findings associated with GERD, the physical exam should focus on conditions that might suggest an alternative explanation for the

patient’s symptoms. These include recent weight loss or progressive inability to tolerate solids and liquids (malignancy), atypical symptoms associated with exertion (coronary artery disease or asthma), or diarrhea (irritable bowel syndrome).

The presence of abdominal surgical scars or abdominal wall hernias is important to identify if laparoscopic LES augmentation surgery is being considered as they may make access to the peritoneal cavity and the gastroesophageal (GE) junction challenging.

Laparoscopic LES augmentation surgery, which involves placement of a magnetic device around the GE junction, is considered not safe for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients should be aware of this contraindication prior to surgery.

Table 1: Contraindications for Undergoing Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Establishing GERD as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms is critical before proceeding with any intervention. Patients may have subjective complaints of heartburn or dysphagia that are unrelated to their reflux disease. The four diagnostic tests that are most commonly used to establish a diagnosis are upper endoscopy, barium esophagram, pH testing, and manometry.

Upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD])

All patients undergoing an antireflux procedure should have an EGD.

EGDs can identify the presence of hiatal hernias and rule out other pathology, which may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms, such as peptic ulcer disease or malignancy.

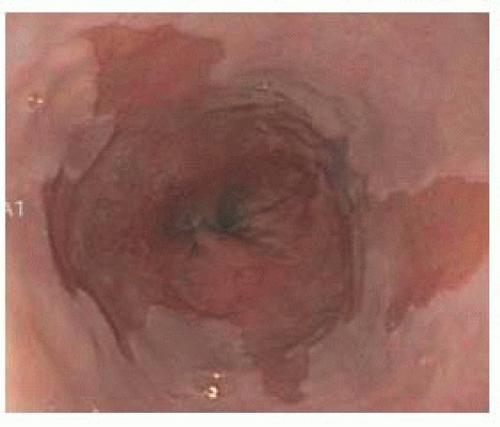

GERD-related complications such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal strictures can also be identified (FIG 1).

Ambulatory pH testing

This is considered to be the gold standard test for diagnosing the presence of symptomatic GERD.

Patients should typically not be taking their antireflux medications when the study is performed.

pH testing can be performed via catheter-based systems (i.e., 24-hour pH probe testing) or wireless systems (i.e., 48-hour Bravo testing).

Both catheter-based and wireless systems allow for the quantification of six variables including total/upright/supine time that the pH is less than 4, number of reflux episodes, number of episodes longer than 5 minutes, and longest episode. These variables can be combined to calculate the “DeMeester score,” which is used by many surgeons as definitive evidence for the presence of GERD.1

Barium esophagram

This is a dynamic fluoroscopic study that characterizes both anatomic and functional aspects of the esophagus. It involves multiple swallows of barium and bariumcoated solid food.

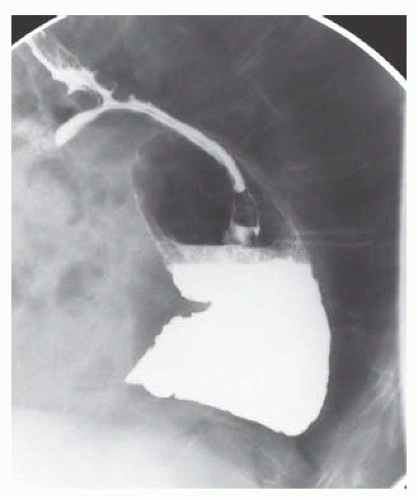

The two most important things to characterize with a barium esophagram are the position of the GE junction relative to the diaphragmatic hiatus and overall esophageal motility. The presence of a large hiatal hernia (FIG 2) or significant esophageal dysmotility is a contraindication for any of the three procedures.2

Esophagrams can also identify the presence of reflux that is characterized by the spontaneous reflux of barium back into the esophagus. However, they are less sensitive than pH studies and thus a negative finding here does not rule out GERD.

Video recording of this study is crucial because it allows the surgeon to actively assess esophageal peristalsis and the functional significance of hiatal hernias.

Manometry

Esophageal manometry uses pressure transducers within a transnasal catheter to provide data regarding the LES resting pressure, LES abdominal and total length, and adequacy of LES relaxation. It also characterizes esophageal motility by quantifying the amplitude, duration, and propagation of each contraction.

The presence of significant esophageal dysmotility is a contraindication for all three procedures.

Multichannel impedance testing and gastric emptying studies are also used on occasion to identify nonacidic GERD and assess gastric functionality, respectively.

FIG 1 • The presence of Barrett’s esophagus is a contraindication to TIF, radiofrequency energy application, and laparoscopic LES augmentation surgery. |

TECHNIQUES

TRANSORAL INCISIONLESS FUNDOPLICATION

Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007, the only TIF device that is currently available for use in the United States is the EsophyX device (EndoGastric Solutions, Redmond, WA).

EsophyX re-creates the LES by plicating the distal esophagus and the gastric cardia together, thus creating an antireflux valve similar to that of a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.

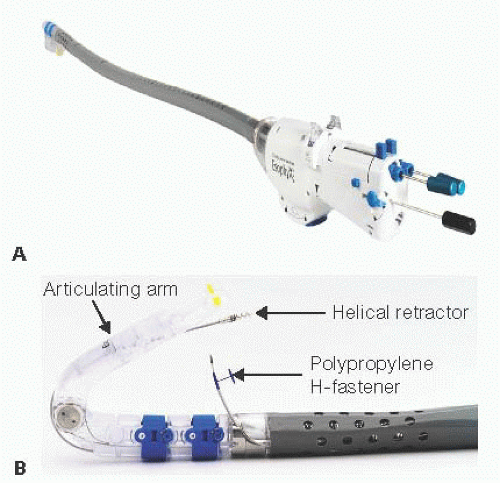

The device consists of a handle, an 18-mm diameter shaft, a tissue invaginator composed of holes in the side of the device (which are connected to a suction device), an articulating arm, which approximates gastric and esophageal tissue and deploys the tissue fasteners, a helical screw, two stylets, and 20 polypropylene H-fasteners (10 plication sets) (FIG 3).

Preoperative Planning

At our institution, general anesthesia is administered and the procedure is performed in the operating room.

Nasotracheal intubation is performed so the oropharynx can be used entirely for the EsophyX device. A bite block is placed to protect the teeth from the device and scope.

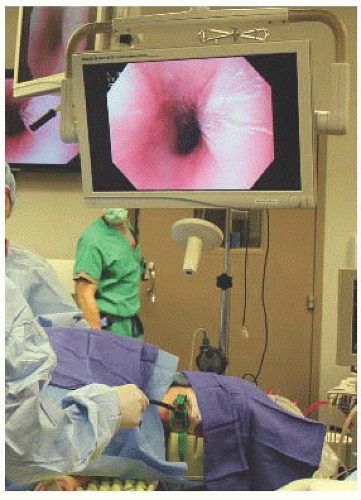

Two physicians perform the procedure. One manipulates the endoscope while the other controls the device.

Positioning

After intubation, the patient is placed into the left lateral decubitus position with the head elevated slightly (FIG 4).

Prophylactic antibiotics are administered before the procedure begins because transluminal fasteners are placed, which may increase the risk of postoperative infections.

Placement of the Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication Device into the Stomach

Preprocedure endoscopy is performed to verify anatomic landmarks.

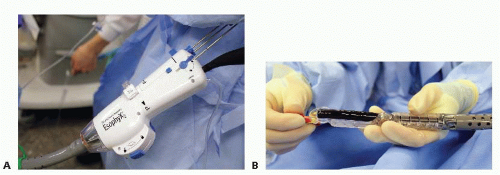

A 56-Fr bougie is inserted into the esophagus and then removed to facilitate subsequent passage of the EsophyX device (FIG 5).

The EsophyX device is lubricated and a standard endoscope is threaded through the device (FIG 6). Both are placed through a bite block and advanced through the esophagus into the stomach.

The scope is advanced into the gastric lumen and then retroflexed to examine the GE junction. Using a standard, high-flow insufflator, the stomach is insufflated with

carbon dioxide to a pressure of 15 mmHg via the working channel of the endoscope. Once the articulating arm is visualized within the stomach, the scope is withdrawn into the device, the articulating arm is flexed, and the scope is then advanced back into the retroflexed position within the gastric lumen (FIG 7).

Anterior Rotational Plication Fasteners

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree