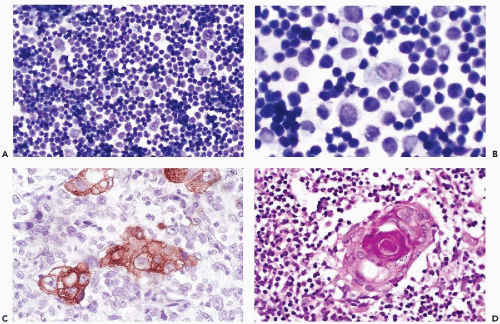

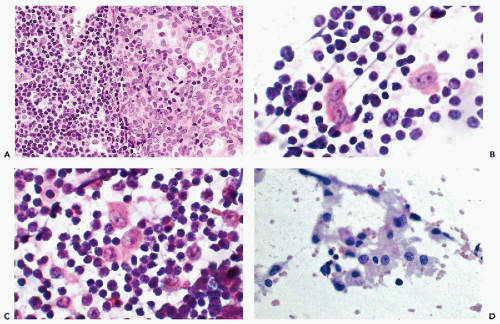

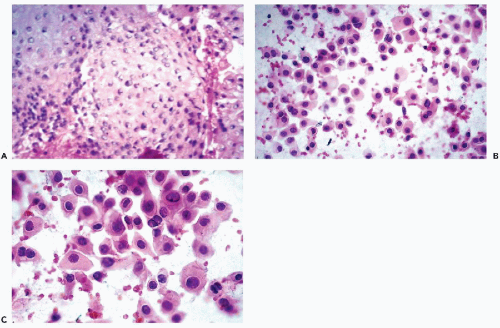

which are similar to squamous pearls and are dispersed throughout the thymus, are formed by epithelial cells (Fig. 37-2D). During the maturation in the thymus, T-lymphocytes (so named because of their thymic origin) are located within spaces formed by the epithelial cells. The lymphocytes, enveloped by the epithelial cells, form so-called lymphoepithelial complexes. T-lymphocytes, unlike the B-lymphocytes, express both CD-4 and CD-8 antigens. In an interesting observation by Nerurkar and Krishnamurthy (2000), which has not yet been confirmed by others, penetration of lymphocytes into the epithelial cells (or emperipolesis) was demonstrated in imprint cytology of the normal thymus.

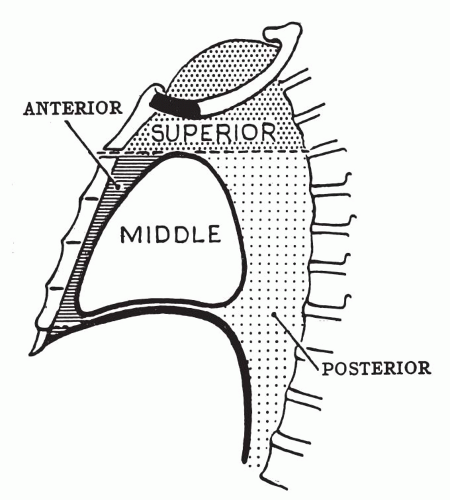

TABLE 37-1 MOST COMMON PRIMARY TUMORS AND SPACE-OCCUPYING LESIONS ACCORDING TO COMPARTMENTS OF THE MEDIASTINUM | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

rare immune disorders. Like myasthenia gravis, these disorders may be the first manifestation of thymoma.

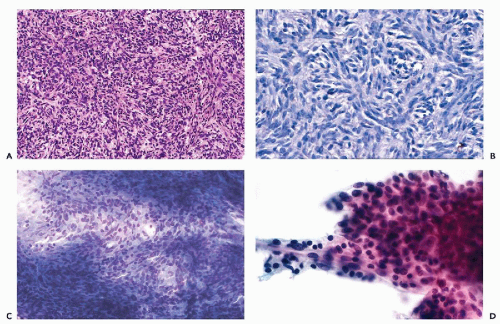

and invasive. In our experience, the best evidence of malignant potential is invasion through the capsule and into the lung or other tissues. The cytology of frankly malignant thymomas (carcinomas) is considered separately below.

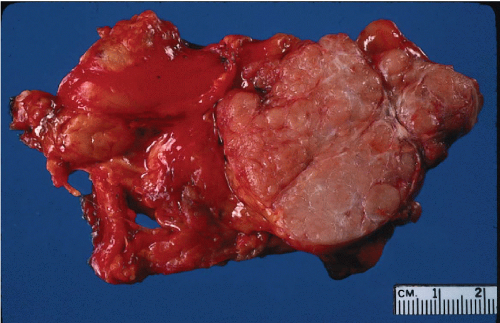

Figure 37-3 Gross appearance of a thymoma. The tumor is sharply circumscribed and soft, pale brown or tan on the cut surface. It is adherent to the adjacent lung (left) but noninvasive. |

intermixed with lymphocytes, should suggest the possibility of thymoma, Slagel et al (1997) reviewed 22 cases of mediastinal tumors in which the needle aspirate contained a predominant spindle cell component, and found only two thymomas and two thymic cysts. The remaining cases included nerve sheath tumors, granulomatous inflammation, Hodgkin’s disease, and a heterogenous group of other tumors.

Positive chromogranin staining of tumor cells can be used to confirm the diagnosis when in doubt.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree