Chapter 6

The lymphatic system

6.1 Lymph and lymph vessels 135

6.2 Lymphatic drainage pathways 136

6.3 Lymph nodes 136

6.4 The spleen 137

6.5 The thymus 138

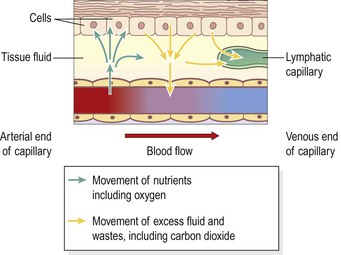

The body cells are bathed in interstitial (tissue) fluid, which leaks constantly out of the bloodstream through the permeable walls of blood capillaries. It is therefore very similar in composition to blood plasma. Some tissue fluid returns to the capillaries at their venous end and the remainder diffuses through the more permeable walls of the lymph capillaries, forming lymph.

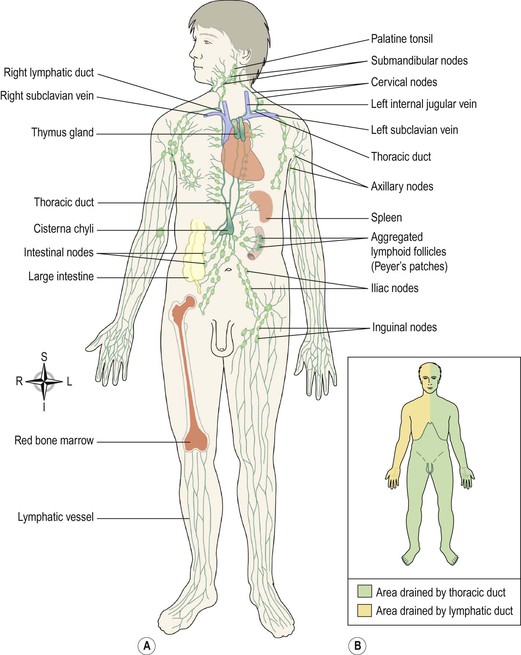

Lymph passes through vessels of increasing size and a varying number of lymph nodes before returning to the blood. The lymphatic system (Fig. 6.1) consists of:

Figure 6.1 The lymphatic system. A. Major parts of the lymphatic system. B. Regional drainage of lymph.

The first sections of this chapter explore the structures and functions of the organs listed above. In the final section, the consequences of disorders of the immune system are considered. The main effects of ageing on the lymphatic system relate to declining immunity, described in Chapter 15 (p. 384).

Functions of the lymphatic system

Tissue drainage

Every day, around 21 litres of fluid from plasma, carrying dissolved substances and some plasma protein, escape from the arterial end of the capillaries and into the tissues. Most of this fluid is returned directly to the bloodstream via the capillary at its venous end, but the excess, about 3–4 litres of fluid, is drained away by the lymphatic vessels. Without this, the tissues would rapidly become waterlogged, and the cardiovascular system would begin to fail as the blood volume falls.

Absorption in the small intestine (Ch. 12)

Fat and fat-soluble materials, e.g. the fat-soluble vitamins, are absorbed into the central lacteals (lymphatic vessels) of the villi.

Immunity (Ch. 15)

The lymphatic organs are concerned with the production and maturation of lymphocytes, the white blood cells responsible for immunity. Bone marrow is therefore considered to be lymphatic tissue, since lymphocytes are produced there.

Lymph and lymph vessels

Lymph

Lymph is a clear watery fluid, similar in composition to plasma, with the important exception of plasma proteins, and identical in composition to interstitial fluid. Lymph transports the plasma proteins that seep out of the capillary beds back to the bloodstream. It also carries away larger particles, e.g. bacteria and cell debris from damaged tissues, which can then be filtered out and destroyed by the lymph nodes. Lymph contains lymphocytes (defence cells, p. 380), which circulate in the lymphatic system allowing them to patrol the different regions of the body. In the lacteals of the small intestine, fats absorbed into the lymphatics give the lymph (now called chyle), a milky appearance.

Lymph capillaries

These originate as blind-end tubes in the interstitial spaces (Fig. 6.2). They have the same structure as blood capillaries, i.e. a single layer of endothelial cells, but their walls are more permeable to all interstitial fluid constituents, including proteins and cell debris. The tiny capillaries join up to form larger lymph vessels.

Nearly all tissues have a network of lymphatic vessels, important exceptions being the central nervous system, the cornea of the eye, the bones and the most superficial layers of the skin.

Larger lymph vessels

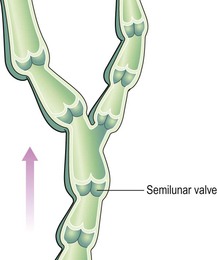

Lymph vessels are often found running alongside the arteries and veins serving the area. Their walls are about the same thickness as those of small veins and have the same layers of tissue, i.e. a fibrous covering, a middle layer of smooth muscle and elastic tissue and an inner lining of endothelium. Like veins, lymph vessels have numerous cup-shaped valves to ensure that lymph flows in a one-way system towards the thorax (Fig. 6.3). There is no ‘pump’, like the heart, involved in the onward movement of lymph, but the muscle layer in the walls of the large lymph vessels has an intrinsic ability to contract rhythmically (the lymphatic pump).

In addition, lymph vessels are compressed by activity in adjacent structures, such as contraction of muscles and the regular pulsation of large arteries. This ‘milking’ action on the lymph vessel wall helps to push lymph along.

Thoracic duct

This duct begins at the cisterna chyli, which is a dilated lymph channel situated in front of the bodies of the first two lumbar vertebrae. The duct is about 40 cm long and opens into the left subclavian vein in the root of the neck. It drains lymph from both legs, the pelvic and abdominal cavities, the left half of the thorax, head and neck and the left arm (Fig. 6.1A and B).

Right lymphatic duct

This is a dilated lymph vessel about 1 cm long. It lies in the root of the neck and opens into the right subclavian vein. It drains lymph from the right half of the thorax, head and neck and the right arm (Fig. 6.1A and B).

Lymphatic organs and tissues

Lymph nodes  6.3

6.3

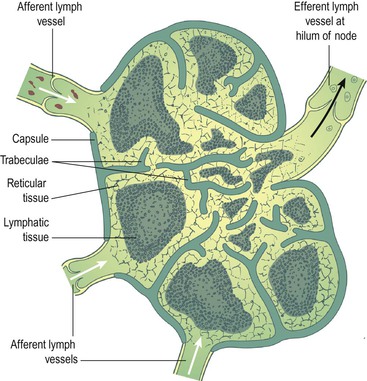

Lymph nodes are oval or bean-shaped organs that lie, often in groups, along the length of lymph vessels. The lymph drains through a number of nodes, usually 8–10, before returning to the venous circulation. These nodes vary considerably in size: some are as small as a pin head and the largest are about the size of an almond.

Structure

Lymph nodes (Fig. 6.4) have an outer capsule of fibrous tissue that dips down into the node substance forming partitions, or trabeculae. The main substance of the node consists of reticular and lymphatic tissue containing many lymphocytes and macrophages. Reticular cells produce the network of fibres that provide internal structure within the lymph node. The lymphatic tissue contains immune and defence cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages.