Chapter 7

The Lumbar Region

Lumbar Lordosis and Characteristics of Typical Lumbar Vertebrae,

Developmental Considerations and the Lumbar Curve (Lordosis),

Lumbar Vertebral Foramen and Vertebral Canal

Unique Aspects of the Lumbar Vertebrae

Ligaments and Intervertebral Discs of the Lumbar Region

Lumbar Anterior Longitudinal Ligament

Lumbar Posterior Longitudinal Ligament

Lumbar Intertransverse Ligaments

Ranges of Motion in the Lumbar Spine

Soft Tissues of the Lumbar Region: Nerves and Vessels

The lumbar portion of the vertebral column has the ideal structure to simultaneously optimize the functions of mobility and stability (Putz & Müller-Gerbl, 1996). This region of the spine is sturdy and is designed to carry the weight of the head, neck, trunk, and upper extremities. However, pain in the lumbar region is one of the most common complaints of individuals, experienced by approximately 80% of the population at some time in their lives (Nachemson, 1976; Jonsson, 2000). The estimated annual cost for low back pain claims in the United States in 1996 was $12.2 billion (Dagenais, Caro, & Haldeman, 2008) and is undoubtedly greater than that today. The total annual costs of treatment, loss of productivity, and resulting disability have been estimated to be more than $28 billion in the United States (Rizzo, Abbott, & Berger, 1998). Low back pain is the most common complaint of patients who are seen at clinics that deal primarily with musculoskeletal conditions. Low back pain of mechanical origin is the most frequent subtype found in this group (Cramer et al., 1992). The most common sources of low back pain are the lumbar zygapophysial joints (Z joints) and intervertebral discs (IVDs) (Bogduk, 1985).

1. Problems with the lumbar region:

a. The Z joints (facet joints; see Figs. 7-3 through 7-6). Increased weight borne by these joints can be a direct cause of back pain. These joints also are susceptible to arthritic changes (e.g., osteoarthritis; arthritis associated with wear and tear).

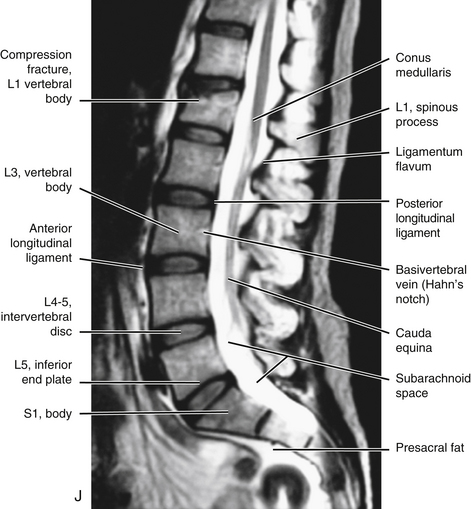

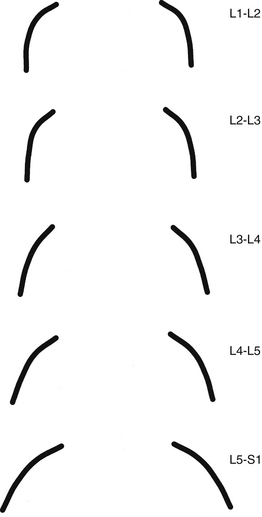

FIG. 7-4 Orientation of lumbar Z joints. Notice the changes from L1-2 to L5-S1. (From Taylor JR & Twomey LT. [1986]. Age changes in lumbar zygapophyseal joints: observations on structure and function. Spine, 11, 739-745.)

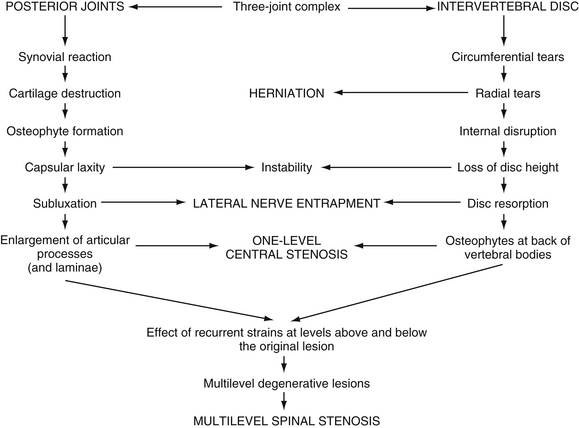

FIG. 7-6 The process of Z joint and disc degeneration and the interrelation between the two. (From Kirkaldy-Willis WH et al. [1978]. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine, 3, 319-328.)

b. The intervertebral discs (IVDs) absorb most of the increased stress received by the low back in bipeds. The discs may bulge or protrude, and by doing so compress the spinal nerves that exit behind them (see Figs. 7-25, 7-26, 11-10, and 11-11). Such protrusion can result in back pain that also has a sharp radiation pattern into the thigh and sometimes into the leg and foot. This type of pain is frequently described as feeling like a “bolt of lightning” or a “hot poker” (see Chapter 11). The IVDs may undergo degeneration also. This narrows the space between the vertebrae, which may result in arthritic changes and additional pressure on the Z joints (see Chapters 2 and 14). The discs themselves are supplied by sensory nerves and therefore can be a direct source of back pain (i.e., they do not have to compress neural elements to cause back pain).

Note: The lumbosacral region, between L5 and the sacrum, receives the brunt of the biomechanical stress of the biped spine. The lumbosacral joints (interbody joint and left and right Z joints between L5 and the sacrum) are a prime source of low back pain. In addition to the biomechanical stresses, the opening for the spinal nerve at this level is the smallest in the lumbar region, making it particularly vulnerable to IVD protrusions and compression from other sources.

c. The muscles of the low back in bipeds are needed to hold the spine erect (erector spinae muscles; see Chapter 4). Therefore when they are required to carry increased loads (this sometimes includes the added weight of a protruding abdomen), these muscles can be torn (strained).

2. The sacroiliac joints are the joints between the sacrum and the left and right ilia. The weight carried in the upright posture also can result in damage to the sacroiliac joint, another source of low back pain (see Chapter 8).

Lumbar Lordosis and Characteristics of Typical Lumbar Vertebrae

Developmental Considerations and the Lumbar Curve (Lordosis)

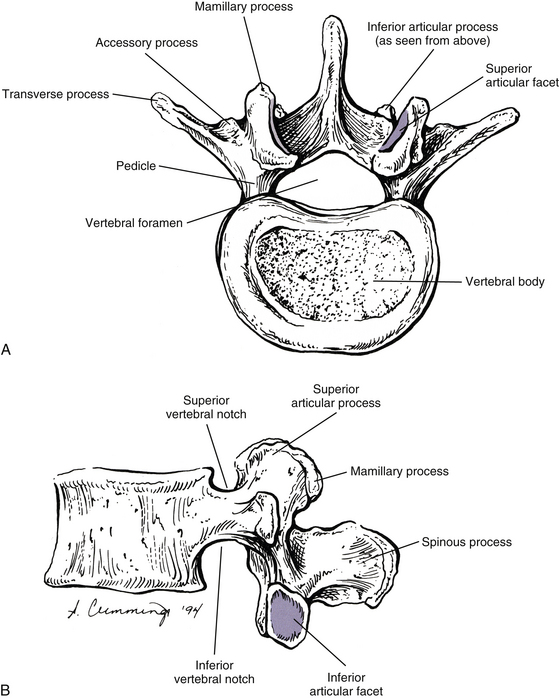

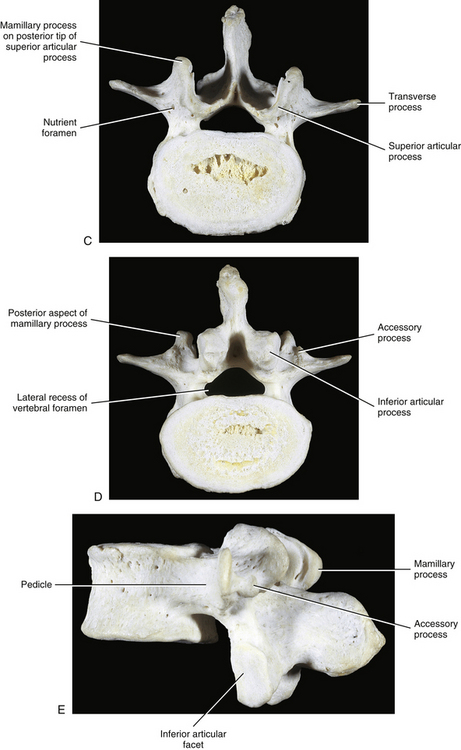

The development of lumbar vertebrae is similar to the development of typical vertebrae in other regions of the spine (see Chapter 12). Two additional secondary centers of ossification on each vertebra are unique to the lumbar region. This brings the total number of secondary centers of ossification per lumbar vertebra to seven. These additional centers are located on the posterior aspect of the superior articular processes and develop into the mamillary processes.

Between 2 and 16 years of age, the lumbar vertebrae grow twice as fast as the thoracic vertebrae. Because the anteroposterior curves of these two regions face in opposite directions (thoracic kyphosis versus lumbar lordosis), the posterior elements of thoracic vertebrae probably grow faster than their vertebral bodies; the reverse (lumbar vertebral bodies grow faster than their posterior elements) is true in the lumbar region (Clarke et al., 1985).

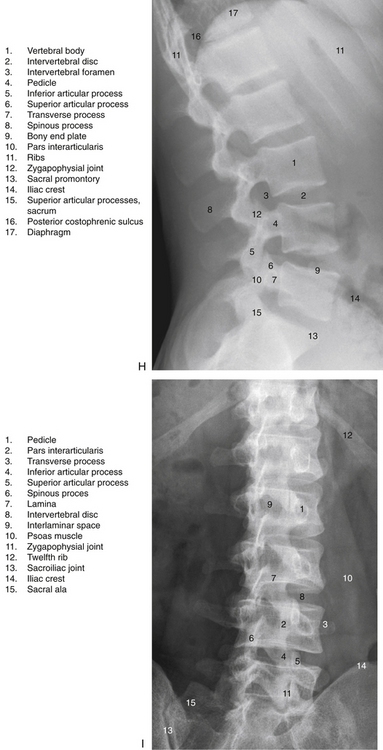

Normally the lumbar lordosis is more prominent than the cervical lordosis. The lumbar lordosis extends from T12 to the L5 IVD, and the greatest portion of the curve occurs between L3 and L5 (Fig. 7-1). The lordosis is greater in the standing than the seated positions (De Carvalho et al., 2010). The lumbar lordosis is created by the increased height of the anterior aspect of the L4 and L5 lumbar vertebral bodies and all of the lumbar IVDs, with the discs contributing more to the lordosis than the increased height of the vertebral bodies.

Either an increase or a decrease of the lumbar lordosis may contribute to low back pain (Mosner et al., 1989). This has sparked an interest in measurement of the lumbar curve; as a result, the lumbar curve has been measured in a variety of ways. One method, developed by Mosner and colleagues (1989), used measurements from lateral x-ray films taken with the patient in the supine position. A line was drawn across the superior vertebral end plate of L2 and another across the superior aspect of the sacral body. These two lines were continued posteriorly until they intersected, and the angle between them was measured. Using this method, angles of 47 and 43 degrees were found to be normal for women and men, respectively. This is in agreement with the values given by other authors (Standring et al., 2008).

Another relatively common method of measuring the lumbar lordosis calls for passing a line across the superior aspect of the body of L1 and another such line across the body of the first sacral segment, and then measuring the angle formed by the intersection of the continuation of the two lines. However, care must be taken when making such measurements. Normally the first lumbar vertebral body is slightly taller anteriorly than posteriorly; however, a relatively frequent anomaly is for the first lumbar vertebral body to be wedge-shaped, so that it is shorter anteriorly than posteriorly. Such wedging of the vertebra being used as a landmark for measurement can cause significant variation of measurements of the lumbar lordosis (Worril & Peterson, 1997).

In the past, many clinicians incorrectly assumed that the lumbar lordosis in the black population was greater than that in the white population, but this has been found to be incorrect; the lordosis is appromimately the same in both races (Mosner et al., 1989).

Clinical Considerations

Certain individuals develop a painful degenerative lumbar kyphosis that is characterized by disc and vertebral body wedging and weakness of lumbar paraspinal muscles. This condition may be related to a prolonged working posture in flexion. For example, a higher incidence of this condition has been found in Japanese dairy farmers when compared with Japanese field farmers. The working posture of the former group calls for long periods of forward flexion while squatting. This posture is maintained for the majority of each working day throughout the workers’ careers, which can last for many decades (Takemitsu et al., 1988). Such prolonged flexion is thought to cause remodeling of the vertebral bodies of the lumbar region so that they are shorter anteriorly than posteriorly.

The lumbar lordosis is often significantly increased in achondroplasia. This can lead to a marked compensatory thoracic (thoracolumbar) kyphosis, which can be severe in some cases (Giglio et al., 1988).

A high incidence of scoliosis (64%) exists in the lumbar region of individuals with Marfan syndrome. Other lumbar vertebral anomalies associated with Marfan syndrome include a high incidence of transitional lumbosacral segments (18%), concavity of both the superior and inferior aspects of the vertebral bodies (biconcavity), and longer than normal transverse processes (Tallroth et al., 1995).

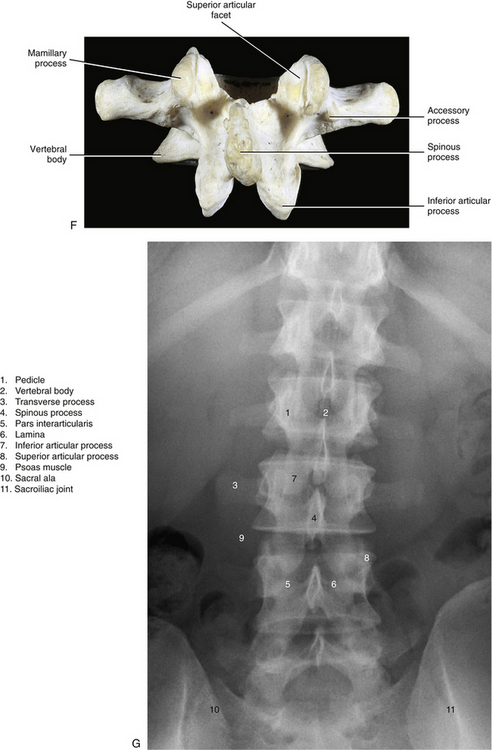

Vertebral Bodies

When viewed from above, the vertebral bodies of the lumbar spine are large and kidney-shaped with the concavity facing posteriorly (Fig. 7-2). However, L5 is more elliptical in shape. In addition, the inferior and superior bony end plates of adjacent vertebrae sharing the same IVD are similar in size and shape. Although the lumbar vertebral bodies of males generally have greater dimensions than those of females, the shapes of the vertebral bodies are similar (Hall et al., 1998). The superior surfaces of the vertebral bodies possess small elevations along their posterior rim. These represent remnants of the uncinate processes of the cervical region. The inferior surfaces of the vertebral bodies have two small notches along their posterior rim. These notches correspond to the uncinate-like elevations of the vertebra below. These elevations and notches have been used as landmarks on x-ray films as a means for evaluating normal and abnormal movement between adjacent lumbar segments (Dupuis et al., 1985).

The volume of the lumbar vertebral bodies (average 35 cm3; range 19.7 to 61.5 cm3) is greater in males than females and increases from L1 to L4, with L5 having a smaller volume than L4 (Limthongkul et al., 2010). The vertebral bodies are wider from side to side (lateral width) than from front to back. The L4 and L5 vertebral bodies are taller in front (anteriorly) than behind. The reverse is true for L1 and L2, although the difference in heights is less, and the anterior and posterior heights of L3 are approximately the same (Masharawi et al., 2008). Therefore as mentioned, the L4 and L5 vertebral bodies are partially responsible for the creation and maintenance of the lumbar lordosis, which is most pronounced from L3 to L5.

Normally, the lateral width of the lumbar vertebrae increases from L1 to L3. L4 and L5 are somewhat variable in width (Standring et al., 2008). Ericksen (1976, 1978) found that the L1-4 vertebral bodies (he did not study L5) became wider from side to side with age. Also, he noted a decrease in height of the vertebral body’s anterior aspect, corresponding with an increase in its lateral width, in both males and females. Further, the increase in lateral width in males was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in height of the vertebral body’s posterior aspect (Erickson, 1976, 1978). Masharawi and colleagues (2008) found a “left lateral wedging” of L1, L2, and L5, with the superior-inferior height of the right side of these vertebrae being greater than that of the left side. The wedging was more common in females than in males. See Chapter 6, Vertebral Bodies for further details on lateral wedging of vertebral bodies.

Up to 90% of the compressive loads received by the vertebral bodies are carried by the inner cancellous (trabecular) bone (Silva, Keaveny, & Hayes, 1997); however, this may be an overestimation (Cao, Grimm, & Yang, 2001). The remaining 10% (or more) of the compressive loads are carried by the thin outer cortical shell of the vertebral bodies (Silva, Keaveny, & Hayes, 1997). However, with the bone loss associated with osteoporosis a higher percentage of the compressive loads is carried by the outer cortical shell of bone (Cao, Grimm, & Yang, 2001).

Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, the bony end plates of the vertebral bodies are particularly important in resisting compressive loads placed on the spine. Oxland and colleagues (2003) found that removal of the bony end plates decreased the ability of the vertebral bodies to resist compression fracture (2003) found that removal of the bony end plates decreased the ability of the vertebral bodies to resist compression fracture by 66%. The end plates of the lumbar region are weakest in the center, and strongest posterolaterally. In addition, the inferior end plates are stronger than the superior ones, and the sacral end plate is similar in strength to the inferior lumbar bony end plates (Grant, Oxland, & Dvorak, 2001).

The trabeculae of vertebral bodies adapt to the external loads placed on them (Bian et al., 2011); however, this trabecular “plasticity” diminishes significantly after the age of 50 years (Cvijanovic et al., 2004). The decreased trabecular plasticity (along with decreased trabecular size) could plausibly contribute to vertebral body compression fractures in the elderly populations.

The blood supply to the lumbar vertebral bodies is extensive and complex (Bogduk, 2005). Each lumbar segmental artery gives off up to 20 primary periosteal arteries as it courses across the anterolateral aspect of the vertebral body. The posterior aspect is supplied by many branches of the anterior vertebral canal artery. The anterior vertebral canal artery refers to the anterior branch of the artery that passes through the IVF. The artery that passes through the IVF sometimes is known as the spinal ramus of the (lumbar) segmental artery.

The end branches of periosteal arteries form a ring around both the superior and inferior margins of the vertebral body. These rings are known as the metaphyseal anastomoses (superior and inferior). They not only help to supply the metaphyseal region of the vertebral body, but also send penetrating branches (metaphyseal arteries) to the region of the vertebral end plate (Bogduk, 2005). A dense capillary network is associated with the superior and inferior vertebral end plates. This network receives contributions from the metaphyseal and nutrient arteries.

Nutrient arteries also arise from the anterior vertebral canal arteries. The nutrient arteries enter the center of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body, pass deep within the substance of the cancellous bone of the vertebral body’s center, and then form superior (ascending) and inferior (descending) branches. In addition to giving off periosteal arteries, the lumbar segmental arteries also send branches that enter the cancellous bone of the anterior and lateral aspects of the vertebral bodies. These branches enter along the superior-to-inferior midpoint of the vertebral bodies. Known as the equatorial arteries, these vessels are similar to the nutrient arteries in that they also give rise to ascending and descending branches deep within the substance of the vertebral bodies (Bogduk, 2005). See Chapter 2 and Figure 2-3 for further details on the blood supply to and venous drainage of typical vertebrae.

The lumbar vertebral bodies serve as attachment sites for several structures. Table 7-1 lists those structures that attach to the lumbar vertebral bodies.

Table 7-1

Attachments to Lumbar Vertebral Bodies

| Region | Structure(s) Attached |

| Anterior surface | Anterior longitudinal ligament on superior and inferior borders |

| Posterior surface | Posterior longitudinal ligament on superior and inferior borders |

| Lateral surface | Crura of diaphragm (anterolateral surface of left L1 and L2 and right L1, L2, and L3) Origin of psoas major muscle (posterolateral aspect of superior and inferior surface of all lumbars); series of tendinous arches between vertebral attachments of psoas major muscle creates concave openings between arches and vertebral bodies, allowing for passage of segmental arteries, veins, and gray communicating rami of sympathetic chain |

From Standring S et al. (2008). Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Clinical Considerations

Osteophytes of the lumbar vertebral bodies can be large. They are much more prominent laterally than anteriorly (the opposite of what is commonly found in the thoracic region), and usually they are completely absent anteriorly at the L3-4 and L4-5 levels. This seems to be associated with the pulsing action of the abdominal aorta and proximal portions of the common iliac arteries (Edelson & Nathan, 1988).

Fractures of the secondary centers of ossification associated with the superior and inferior vertebral end plates, the ring apophyses (also known as anular apophyses; see Chapters 2 and 12), have been reported. These fractures are rare but occur most frequently during adolescence. The signs and symptoms of apophyseal ring fractures resemble those of IVD protrusions. Such fractures may be unnoticed on conventional x-ray films. Sagittally reformatted computed tomography (CT) is currently the imaging modality that shows these fractures to best advantage (Thiel, Clements, & Cassidy, 1992).

Pedicles

The pedicles of the lumbar spine are short but strong (see Fig. 7-2). They attach lower on the vertebral bodies than the pedicles of the thoracic region, but higher than those of the cervical region. Therefore each lumbar vertebra has a superior vertebral notch that is less distinct than that of the cervical region. On the other hand, the inferior vertebral notch of lumbar vertebrae is prominent.

The size of the pedicles, like the size of many spinal structures, can vary among individuals of different ethnic backgrounds. Such normal ethnic variations should be kept in mind when evaluating x-ray films and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. For example, the width and length of the pedicles of individuals of East Indian descent are less than those of whites (Mitra, Datir, & Jadhav, 2002; Acharya, Dorje, & Srivastava, 2010).

The role of the pedicles in the transfer of loads is discussed in Chapter 2. More study is needed to confirm the role played by the pedicles in the transfer of loads in the upper lumbar region (Pal et al., 1988). However, the trabecular pattern of the L4 and L5 pedicles seems to indicate that most loads placed on these vertebrae may be transferred from the vertebral bodies to the region of the posterior arch, specifically to the pars interarticularis (see Laminae).

Transverse Processes

Each transverse process (TP) (left and right) of a typical lumbar vertebra projects posterolaterally from the junction of the pedicle and the lamina of the same side (see Fig. 7-2). It lies in front of (anterior to) the articular processes and behind (posterior to) the lumbar IVF.

The lumbar TPs are quite long, the TPs of L3 being the longest. As with other components of lumbar vertebrae, the left and right transverse processes are asymmetric in length, with the left transverse process being longer than the right (same as the thoracic region). In addition, the pedicles of males are larger than those of females (Masharawi & Salame, 2011). The distance between the apices of the left and right TPs is much greater on L1 than T12. This distance increases on L2 and is the greatest in the entire spine on L3. The intertransverse distance between the left and right L4 TPs is smaller than that of L3 and is even smaller for L5. The lumbar TPs are flat and thin from front to back. They are also narrower from superior to inferior than their thoracic counterparts. They possess neither articular facets (as do thoracic TPs) nor foramina of the transverse processes (as do cervical TPs). The anterior aspects of the lumbar TPs also are known as the costal elements, and they occasionally develop into ribs. This happens most frequently at L1.

The lateral aspect of the anterior surface of the lumbar TPs is creased by a ridge that runs from superior to inferior. This ridge is created by the anterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. The middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia attaches to the apex of the TPs. Table 7-2 lists structures that attach to the lumbar TPs.

Table 7-2

Attachments to Lumbar Transverse Processes

| Region | Structure(s) Attached |

| Anterior surface | Psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles Anterior layer of thoracolumbar fascia (separates psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles) Medial and lateral arcuate ligaments (lumbocostal arches) (L1) |

| Apex | Middle layer of thoracolumbar fascia Iliolumbar ligament (L5, occasionally L4) |

| Superior border | Lateral intertransversarius muscle |

| Inferior border | Lateral intertransversarius muscle |

| Posterior surface | Deep back muscles (longissimus thoracis) |

From Standring S et al. (2008). Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Accessory Processes

The accessory processes are unique to the lumbar spine. Each accessory process projects posteriorly from the junction of the posterior and inferior aspect of the TP with the corresponding lamina. These processes serve as attachment sites for the longissimus thoracis muscles (lumbar fibers) and the medial intertransversarii lumborum muscles (Standring et al., 2008). (See Figure 4-5, B, for the attachment of the medial intertransversarii lumborum muscles to the accessory processes.)

Articular Processes

Left and right superior articular processes are formed on every vertebrae of the lumbar spine (see Fig. 7-2). Each superior articular process possesses a hyaline cartilage–lined superior articular facet that is oriented in a vertical plane. That is, these facets are not angled to the vertical plane like the superior articular facets of the cervical and thoracic regions.

All the lumbar superior articular facets face posteriorly and medially. The articular surface of a typical superior articular facet can be gently curved with the concavity facing medially (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4), or the articular surface can be angled abruptly. When the articular surface is angled abruptly, two relatively distinct articulating surfaces are formed. One surface faces posteriorly and forms almost a 90-degree angle with the second surface, which faces medially. As with the curved facet, the concavity faces posteriorly and medially. In either case (curved or angled articular surface), the shape conforms to the inferior articular facet of the vertebra above. The hyaline cartilage of the central region of the superior articular facet (the area of greatest concavity) increases in thickness with age, probably because this region receives much of the load during flexion of the spine (Taylor & Twomey, 1986). Also, the articular processes may fracture as a result of age-related degeneration (Kirkaldy-Willis et al., 1978).

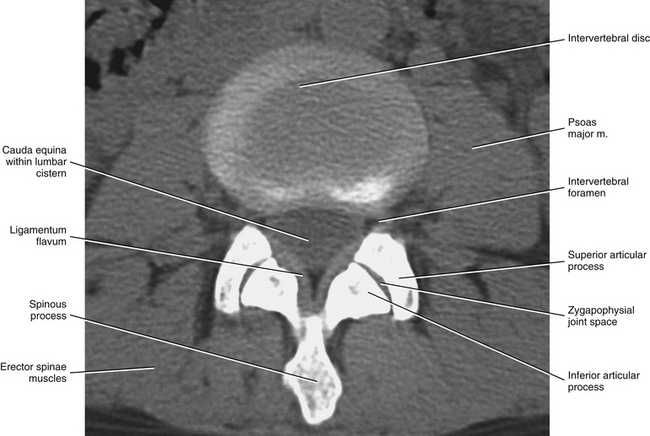

The orientation of the superior articular facets varies from one vertebral level to another (see Fig. 7-4). A line passed across each superior articular facet, on transverse CT scans, shows that the L4 superior facets (and therefore the L3-4 Z joints) are more sagittally oriented than the L5 facets. Also, the S1 superior facets (and therefore the L5-S1 Z joints) are more coronally oriented than the L4 and L5 facets (Van Schaik, Verbiest, & Van Schaik, 1985). (See Zygapophysial Joints for further detail on the orientation of the superior and inferior articular facets.) The angle of the L4-L5 Z joint (i.e., the angle of the superior articular facets) has been found to become more sagittally oriented with age, which may explain the higher incidence of degenerative spondylolisthesis (forward slippage of L4 on L5) at this level in individuals more than 60 years of age (Wang & Yang, 2009). The left and right articular facets are usually symmetrical in orientation (unlike the thoracic facets) (Masharawi et al., 2004) with the exception of the facets that form the L5-S1 articulation where left to right asymmetry (tropism) occurs rather frequently. However, the right facets of L1-L4 are slightly longer from superior to inferior than the left facets (Masharawi et al., 2005).

The mamillary processes (see Fig. 7-2), which project posteriorly from the superior articular processes of lumbar vertebrae, are unique to the lumbar spine. Each mamillary process is a small rounded mound of variable size. Some are almost indistinguishable, whereas others are relatively prominent. The mamillary processes serve as attachment sites for the multifidi lumborum muscles.

Mamillo-Accessory Ligament

A mamillo-accessory ligament (Bogduk, 1981; Lippitt, 1984) is found between the mamillary and accessory processes on the left and right sides of each lumbar vertebra. Occasionally one or more of these ligaments may ossify in the lower lumbar levels (L3-5). The incidence of ossification increases in frequency from L3 to L5. Ossification of these ligaments at L5 occurs at a frequency of 10% (Bogduk, 1981) to 26% (Maigne, Maigne, & Guervin-Surville, 1991). Maigne and colleagues (1991) studied 203 lumbar spines and found that ossification of this ligament at L5 occurred twice as often on the left. They offered no reason to explain why the ligament ossified more frequently on this side. However, they believed the ossification was the result of osteoarthritis, because they found no evidence of ossification on the spines of children and young adults. These authors also stated that an ossified mamillo-accessory ligament could occasionally be seen on standard lumbar x-ray films.

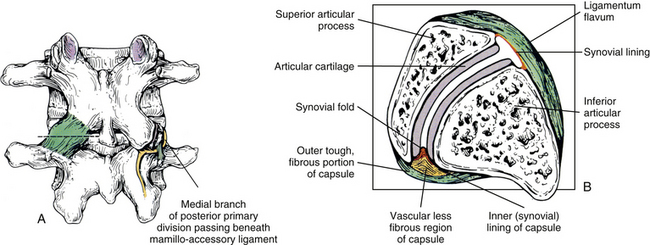

The mamillo-accessory ligament has been described as a tough, fibrous band that may represent tendinous fibers of origin of the lumbar multifidi muscles or fibers of insertion of the longissimus thoracis pars lumborum muscle (Bogduk, 1981). Regardless of its precise structure, the reported purpose of the mamillo-accessory “ligament” is to hold the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the above spinal nerve (e.g., the L2 medial branch is associated with the L3 mamillo-accessory ligament) against (a) the bone between the base of the superior articular process and the base of the transverse process and (b) the Z joint, which is slightly more medial (Fig. 7-5). The medial branch of the dorsal ramus gives off articular branches to the capsule of the Z joint as it passes deep to the mamillo-accessory ligament. The medial branch then continues medially across the vertebral lamina to reach the multifidus muscle (Bogduk, 1981). Therefore the medial branch of the dorsal ramus (posterior primary division) is held within a small osteofibrous canal along the posterior arch of a lumbar vertebra. The medial branch could possibly become irritated or even entrapped within this tunnel, which would result in low back pain. However, more investigation is necessary to determine if such irritation or entrapment occurs and, if so, its frequency (Bogduk, 1981; Maigne, Maigne, & Guerin-Surville, 1991).

Inferior Articular Processes

The inferior articular processes of lumbar vertebrae are convex anteriorly and laterally. They possess inferior articular facets that cover their anterolateral surface. As with the superior articular facets, the inferior ones vary in shape. Even though articular processes vary from one vertebral level to another, and even from one side to another, superior and inferior articulating processes of one Z joint conform to one another. This conformation is such that each inferior articular facet usually fits remarkably well into the posterior and medial concavity of the adjoining superior articular facet. The exception to this is that the inferior articular processes and their facets are less vertically oriented and angle slightly anteriorly to the frontal plane. This orientation (“disharmony” with the superior articular processes) likely enhances motion of the lumbar region (Masharawi et al., 2004).

Zygapophysial Joints

The Z joints have been positively identified as a source of back pain (Mooney & Robertson, 1976; Yamashita et al., 1990; Bogduk, 1992; Dreyfuss & Dreyer, 2001). In addition, Rauschning (1987) states that these joints “display typical degenerative and reparative changes which are known to cause osteoarthritic pain in peripheral synovial joints.” Therefore the lumbar Z joints are highly significant clinically. Because these joints are discussed in detail in Chapter 2, this section focuses on the unique and clinically significant aspects of the lumbar Z joints.

The lumbar Z joints are considered to be complex synovial joints oriented in the vertical plane (Standring et al., 2008). They are fashioned according to the shape of the superior and inferior articular facets (see previous discussion). Therefore the lumbar Z joints are concave posteriorly and even have been described as being biplanar in orientation (Taylor & Twomey, 1986). That is, they have a coronally oriented, posterior-facing, anteromedial component and a large, sagittally oriented, medial-facing, posterolateral component. Taylor and Twomey (1986) state that the lumbar Z joints are coronally oriented in children and that the large sagittal component develops as the individual matures. The sagittal component limits rotation, whereas the coronal component limits flexion. More specifically, the shape of the lumbar Z joints allows a large amount of flexion to occur in the lumbar region, yet the size of the lumbar Z joints is what eventually limits flexion at the end of the normal range of motion. Therefore the long contact surfaces between the coronal component of the superior articular processes and the adjacent inferior articular processes finally limit flexion by “restraining the forward translational component of flexion” (Taylor & Twomey, 1986).

Even though the size of the Z joints eventually limits flexion, approximately 60 degrees of flexion is able to occur in the lumbar region before the bony restraints of the lumbar articular processes prevent further movement. However, the size and shape of the Z joints dramatically limit rotation. By limiting rotation, the Z joints protect the IVDs from rotational injury. During rotation of the lumbar region, distraction (or gapping) occurs between adjacent lumbar articular facets (superior facet of vertebra below and inferior facet of vertebra above) on the side of rotation. For example, right rotation results in gapping of the facets on the right side. Also during rotation, the two opposing facets of the opposite side are pressed together. This causes them to act as a fulcrum for the distracting facets on the side of rotation (Paris, 1983; Cramer et al., 2003). Side posture spinal adjusting, performed by chiropractors and other health practitioners, also causes gapping of the Z joints. The gapping action produced by such adjustive procedures is thought to break-up fibrous adhesions that develop in Z joints that are moving less than normal (are hypomobile) (Cramer et al., 2000, 2002, 2003, 2010).

Variation of Zygapophysial Joint Size and Shape

A considerable degree of variation exists between individual Z joints at different lumbar levels and between the left and right Z joints at the same vertebral level. The shapes range from a slight and gentle curve, concave posteriorly; to a pronounced, dramatic, and posteriorly concave curve; and in some cases to a joint in which the posterior and medial components face one another at an angle of nearly 90 degrees. Generally, the Z joints of the upper lumbar levels are more sagittally oriented than those of the lower lumbar levels (see Fig. 7-4). This makes the lower lumbar joints more susceptible to recurrent rotational strain (Kirkaldy-Willis et al., 1978). However, Z joint osteoarthritis is more prevalent in lower lumbar (L3-L4, L4-L5, and L5-S1) Z joints (particularly at L4-L5) when they are more sagittally oriented (Kalichman et al., 2009).

Biomechanical Considerations

The articular facets do not absorb any of the compressive forces of the spine when humans are sitting erect or standing in a slightly flexed posture. The IVD and vertebral bodies absorb almost all the compressive loads under these conditions. However, when a person stands erect (slight extension), the facets resist approximately 16% (range, 3% to 25%) of the compressive forces between vertebrae. Disc degeneration may lead to increased stress on the Z joints, causing them to resist up to approximately 47% of the loads. This results in pain, not from the articular cartilage, but usually from pressure on the subchondral bone of the articular processes, entrapment of soft tissue between the articular facets, or added strain on the articular capsules (Dunlop, Adams, & Hutton, 1984; Yang & King, 1984; Hutton, 1990). In addition, beyond the limit of normal physiologic flexion, the inferior articular process is forced over the superior articular process, and the compressive loads carried by the facets again increase from those carried in the neutral position (Shirazi-Adl & Drouin, 1987).

Articular Capsules

An articular capsule covers the posterior aspect of each lumbar Z joint (see Fig. 7-5), and the ligamentum flavum covers the anteromedial aspect of the Z joint. The articular capsule is tough, possesses a rich sensory innervation, and is well vascularized (Giles & Taylor, 1987; Ashton et al., 1992).

The bundles of collagen fibers that form the thick outer fibrous layer of a typical lumbar Z joint capsule are oriented in different directions, depending on whether the fibers are located in the superior, middle, or inferior aspect of the capsule. The superior fibers attach laterally to the groove that is located between the mamillary process and posterior ridge of the superior articular process. From here the fibers of the superior capsule course medially across the superior joint recess, attaching to the medial aspect of the laminae of the superior-most vertebrae forming the Z joint. Fibers of the middle part of the Z joint capsule course more horizontally (lateral to medial), beginning from their attachment to the posterior aspect of the mamillary process (on the posterior aspect of the superior articular process) (Yamashita et al., 1996). These fibers then cross the Z joint gap and attach to the medial part of the lamina of the suprajacent vertebra. The fibers just described extend a considerable distance medially and become continuous with the lateral fibers of the interspinous ligament. Finally, the fibers of the more inferior aspect of the capsule course from superomedial to inferolateral, covering the joint space and the inferior end of the inferior Z joint recess. The superomedial fibers attach to the medial and inferior part of the lamina. The bundles of collagen fibers of this inferior aspect of the capsule are longer and thicker than those of the superior aspect of the capsule (Yamashita et al., 1996).

The orientation of the fibers within the tough outer layer of the capsule helps to limit forward flexion (Paris, 1983). The medial-to-lateral arrangement of the fibers in the central part of the Z joint may tend to stabilize the joint during axial rotation, while allowing movement in flexion and extension (Yamashita et al., 1996). The contribution of the lumbar Z joint capsule in stabilizing and perhaps even in helping to limit motion during axial rotation also has been supported by biochemical studies that show evidence of increased capsular resistance to tension in regions of the capsule that would receive the greatest stretch during this motion (Boszczyk et al., 2001). The collagen fibers of the superior and middle aspects of the Z joint are shorter than those of the inferior aspect of the capsule and are thought to be under more tensile stretch than the inferior aspect of the capsule. The posterosuperomedial-most corner of the capsule (just inferior to the superior Z joint recess) is thought to be the area of the capsule that receives the highest tensile stretch (Yamashita et al., 1996). In fact, Yamashita and colleagues (1996) stated that the lumbar Z joint capsules undergo “extensive stretch under physiological loads.”

The collagen fibers of the inferior aspect of the lumbar Z joint capsules are thicker and more heavily innervated than those found in the superior and middle aspects of the capsules. This may be because the inferior aspects of the capsule can be compressed (therefore requiring increased thickness), and even pinched (thus resulting in pain from additional nociceptive nerve endings), during full extension of the lumbar region (Yamashita et al., 1996).

Laterally, fibers of each articular capsule frequently are continuous with the articular cartilage lining the superior articular facet. A gradual transition occurs from the fibrous tissue of the capsule to fibrocartilage and finally to the hyaline cartilage of the superior articular facet (Taylor & Twomey, 1986).

Each capsule has a relatively large superior and inferior recess that extends away from the joint. The capsular fibers (or fibers of the ligamentum flavum, anteriorly) surrounding these recesses are relatively thin and loose, and there may be openings through which neurovascular bundles enter the recesses (Taylor & Twomey, 1986). Paris (1983) states that effusion within the Z joint may enter the superior recess and as little as 0.5 ml of effusion may cause the superior recess to enter the anteriorly located IVF. Once in the IVF, this expanded superior capsular recess may compress the dorsal root ganglion or the exiting spinal nerve, resulting in radiculopathy (see Chapter 11 for a full discussion of radiculopathy). Such a distinct protrusion of the superior recess of the Z joint capsule constitutes an example of a large Z joint synovial cyst (Xu et al., 1991; Bougie, Franco, & Segil, 1996).

Xu and colleagues (1991), in a study of 50 pairs of lumbar Z joints from an elderly population, found that the capsules varied greatly in thickness and regularity. They found that the capsules were “irregularly thickened, amorphous, and calcified in 22 cases.” In addition, they found that in most subjects the synovium of the joint space extended 1 to 2 mm outside the boundaries of the joint in one or more locations. These synovial extensions, which could be considered to be small synovial cysts, maintained communication with the joint space, and were found on both the anterior and posterior aspects of the joint. Anteriorly the spaces most often extended along the posterior border of the ligamentum flavum (64% of Z joints). Sometimes a synovial joint extension extended directly into the ligamentum flavum (8% of cases). Posteriorly the synovial cysts usually extended either laterally along the superior articular process (7% of cases) or medially along the inferior articular process (29%). Extensions were found on both the inferior and superior articular processes in 41% of the Z joints, and no synovial extensions were found in 23% (7% of individuals) of the Z joints. Xu and colleagues (1991) believed that the synovial joint extensions (synovial cysts) probably were more common in the older population (e.g., the specimens in their study) than in younger age groups. They stated that their findings may explain why Z joint arthrography (visualization of the Z joint on x-rays after injection with radiopaque dye) could be successful even when the joint space was not entered with the injecting needle (i.e., the needle could enter a synovial extension).

In another study, Xu, Haughton, and Carrera (1990) visualized the synovial joint extensions (cysts) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Their positive identification of these synovial joint extensions was aided with the injection of paramagnetic contrast medium (gadodiamide, Winthrop Pharmaceuticals). Their imaging was performed on dissected spines using small surface coils, long acquisition times, and thin slice thicknesses. Therefore clear delineation of these extensions is probably still beyond the resolving capabilities of MRI scans obtained in a typical clinical setting. However, Xu and colleagues (1991) thought their results helped to explain the variable appearance of the facet joints on MRI scans. They stated that “the inhomogeneity detected at MR imaging and computerized tomography in the ligamentum flavum near the facet joint most likely represents extension of the joint capsule between the ligamentum flavum and the articular processes…” (Xu et al., 1991).

The superior and inferior recesses are filled with fibrofatty pads. These pads are well vascularized and are lined with a synovial membrane. They also protrude a significant distance into the superior and inferior aspects of the Z joint. Engel and Bogduk (1982) state that adipose tissue pads probably develop from undifferentiated mesenchyme of the embryologic Z joint. Furthermore, they note that in certain instances, mechanical stress to the joint may cause an adipose tissue pad to undergo fibrous metaplasia, which results in the formation of a large fibroadipose meniscoid (an adipose tissue pad with a fibrous tip composed of dense connective tissue, to be differentiated from the normal synovial folds described in Ch 2). The authors believed that both the adipose tissue pads and the normally found synovial folds, or meniscoids, “play some form of normal functional role” (see Fig. 7-5).

Sometimes a fatty synovial fold develops a relatively long fibrous tip that extends a considerable distance between the joint surfaces, where it may become compressed (Taylor & Twomey, 1986). Such protruding synovial folds (again, different from the normal synovial folds) have been associated with the early stages of degeneration (Rauschning, 1987). Rauschning (1987) typically found hemarthrosis and effusion into the Z joints when the meniscal folds of this type were torn or “nipped” between the joint surfaces.

Occasionally the aging process causes a piece of articular cartilage to break from the superior or inferior articular facet. The piece usually breaks along the posterior aspect of the Z joint, parallel to the joint space. However, the attachment to the articular capsule usually is maintained. The result is the presence of a large, fibrocartilaginous meniscoid inclusion within the joint. Taylor and Twomey (1986) reported that the formation of this type of meniscoid is partially caused by the regular pulling action on the posterior articular capsule by the multifidi muscles that originate from these capsules. The attachment of the capsule to the periphery of the articular cartilage may then result in the cartilage tears found to run parallel with the joint surface. Again, the torn cartilage fragment is capable of developing into a Z joint meniscoid, which can become interposed between the two surfaces of the joint. The authors also noted that the posterior aspect of the Z joint may open when the multifidi and other deep back muscles relax, allowing the meniscoids and other joint inclusions to bow into the joint space and become entrapped (Kos, Hert, & Sevcik, 2002). The result of this type of entrapment could be (a) loss of motion (locked back), resulting from the cartilage being lodged between two opposing joint surfaces; (b) pain, because the meniscoids remain attached and therefore might put traction on the pain-sensitive joint capsule; or (c) both decreased motion and pain.

As described in Chapter 2, the Z joint articular capsule receives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the posterior primary division of three consecutive spinal nerves. The sensory receptors in the Z joint capsule are both free nerve endings (for nociception) and mechanoreceptors (for proprioception). Consequently, the Z joint capsules not only are potential sources of low back pain (i.e., are potential “pain generators”) but also are likely to play a role in lumbar proprioception (Ianuzzi, Pickar, & Khalsa, 2011). Using nerve tracing techniques in rats, Suseki and colleagues (1997)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree