Patient Story

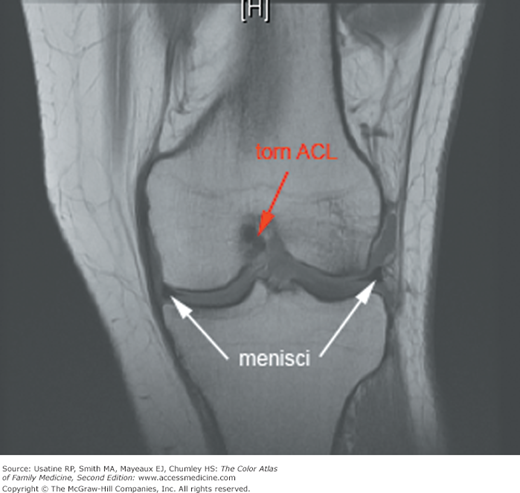

A 33-year-old woman felt a pop in her knee while skiing around a tree. She felt immediate pain and had difficulty walking when paramedics removed her from the slopes. Within a couple of hours, her knee was swollen. On examination the next day, she was able to walk 4 steps with pain. She had a moderate effusion without gross deformity and full range of motion. She had no tenderness at the joint line, the head of the fibula, over the patella, or over the medial or lateral collateral ligaments. She had a positive Lachman test, a negative McMurray test, and no increased laxity with valgus or varus stress. The physician suspected an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, placed her in a long leg range of motion brace, and advised her to use crutches until an evaluation by her physician within the next several days. She was treated with acetaminophen for pain and advised to rest, apply ice, and keep her leg elevated. Later, an MRI confirmed an ACL tear (Figure 106-1).

Introduction

Knee injuries are common, especially in adolescents. Women have a greater risk of knee injuries because of body mechanics. Most knee injuries involve the ACL, meniscus, or medial or lateral collateral ligaments. The mechanism of injury and physical examination findings suggest the type of injury, which can be confirmed by MRI. Treatment includes rest, ice, compression, elevation, and referral to an orthopedic surgeon.

Epidemiology

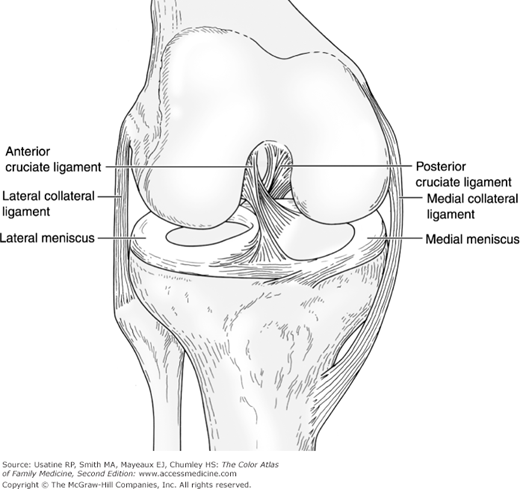

- Knee injuries are the second most common adolescent sporting injury (after ankle injuries)1 and typically are seen in sports requiring pivoting, such as basketball or football. Figure 106-2 shows the normal anatomy of the knee.

- The risk of ACL injury while playing soccer, is 2 to 3 times higher in females than in males after the age of 12 years.2

- The risk of ACL injury was 3.79 times greater in girls in a prospective study of boy and girl high school basketball players in Texas.1

- Incidence of ACL injuries was approximately 3 per 1000 person-years in United States active military personnel, with no difference in gender.3

- Meniscal injuries commonly occur with ACL tears (23% to 65%).4

- Meniscal tears were seen on MRI in 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis, but also seen in 76% of age-matched controls without knee pain.5

- Collateral ligament injuries account for approximately 25% of acute knee injuries.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- ACL injuries occur with sudden deceleration with a rotational maneuver, usually without contact.

- ACL injuries are thought to occur more commonly in women because of decreased leg strength, increased ligamentous laxity, and differences in lumbopelvic core control.

- Acute meniscal injuries occur with a twisting motion on the weight-bearing knee.

- Chronic meniscal tears occur from mechanical grinding of osteophytes on the meniscus in older patients with osteoarthritis.

- Medial collateral and lateral collateral injuries occur from valgus and varus stress, respectively.

Diagnosis

ACL:

- Rotational injury.

- “Pop” reported by patient.

- Unable to bear full weight.

- Effusion within the first few hours.

Meniscal injury:

- Foot planted with femur rotated internally with valgus stress (medial) or femur rotated externally with varus stress (lateral).

- Joint line pain.

- Effusion over the first several hours.

- Usually ambulatory with instability or locking (mechanical) symptoms.

Collateral injury:

- Valgus or varus stress injury.

- Usually ambulatory without instability or locking symptoms.

A complete physical exam of the knee is demonstrated online from the University of British Columbia at http://www.youtube.com/user/BJSMVideos.

- Inspect the knee for effusions—Usually present for an ACL tear.

- Test range of motion—Often normal; inability to extend fully can indicate either a medial meniscal tear or an ACL tear displaced posteriorly.

- Palpate for tenderness—Joint line tenderness may indicate a meniscal tear (likelihood ratio, LR+ = 1.1; LR− = 0.8).6 Tenderness at the head of the fibula or at the patella are 2 of the 5 Ottawa rules for obtaining radiographs; tenderness along the medial or lateral collateral ligament may indicate damage to those ligaments.

- Perform tests for ACL tear—Lachman test (LR+ = 12.4; LR− = 0.14),6 anterior drawer test (LR+ = 3.7; LR− = 0.6),6 pivot shift test (LR+ = 20.3; LR− = 0.4).6

- Patients with ACL tears typically have a history of rotational injury; inability to bear weight; positive provocative tests; normal plain radiographs; and abnormal MRI.

- Perform tests for meniscal tears—McMurray test (LR+ = 17.3; LR− = 0.5).6

- Patients with meniscal tears typically have history of rotational injury with valgus/varus stress or history of osteoarthritis; able to bear weight, commonly with instability or locking; positive McMurray test; normal plain radiographs; and abnormal MRI.

- Perform varus and valgus stress to test the lateral and medial collateral ligaments.

- Patients with injuries to the collateral ligaments typically have a history of valgus/varus stress to extended knee; able to bear weight without instability or locking; laxity with valgus or varus stress testing; normal plain radiographs and abnormal MRI.

- Determine whether or not to obtain plain radiographs (anteroposterior, lateral, intercondylar notch, and sunrise views) to assess for a fracture based on either the Pittsburgh or Ottawa knee rules (the Ottawa rules may be less sensitive in children):

- Pittsburg (99% sensitivity, 60% specificity; tested in population ages 6 to 96 years)6—Obtain x-ray for:

- Recent significant fall or blunt trauma.

- Age younger than 12 years or older than 50 years.

- Unable to take 4 unaided steps.

- Recent significant fall or blunt trauma.

- Ottawa (98.5% sensitivity, 48.6% specificity; LR− = 0.05; tested in 6 studies of 4249 adult patients)7—Obtain x-ray for:

- Age 55 years or older.

- Tenderness at the head of the fibula.

- Isolated tenderness of the patella.

- Inability to flex knee to 90 degrees.

- Inability to bear weight for 4 steps both immediately and in the examination room regardless of limping.

- Age 55 years or older.

- Pittsburg (99% sensitivity, 60% specificity; tested in population ages 6 to 96 years)6—Obtain x-ray for:

- MRI is 95% and 90% accurate in identifying ACL tears and meniscal injuries, respectively (Figures 106-2, 106-3, 106-4).8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree