Learning Objectives

- Understand the basic terms and definitions of indicators

- Understand the main causes of mortality and morbidity through the lifecycle of women and children

- Describe the social, economic, and cultural context of maternal and child health

- Distinguish maternal health issues and interventions from other women’s health issues and describe the relationships between them

- Identify low-cost, effective community-based approaches to interventions

Introduction

Maternal and child health (MCH) refers to the health status and health services provided to women and children. The traditional focus of the disciplines of MCH has been on women in their roles as mothers (childbearing and child rearing) and on children (primarily the healthy survival of infants and young children). MCH indicators are often used to measure the social, economic, and educational status of women as well as community-level access to primary care. MCH was the mainstay of international health and development programs until human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) became an epidemic in many parts of the world.

Remarkable achievements have been made in reducing child and maternal mortality and morbidity. However, of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the only three that will not be achieved by 2015 are those related to MCH: MDGs 3, promote gender equality and empower women; 4, reduce child mortality; and 5, improve maternal health.1

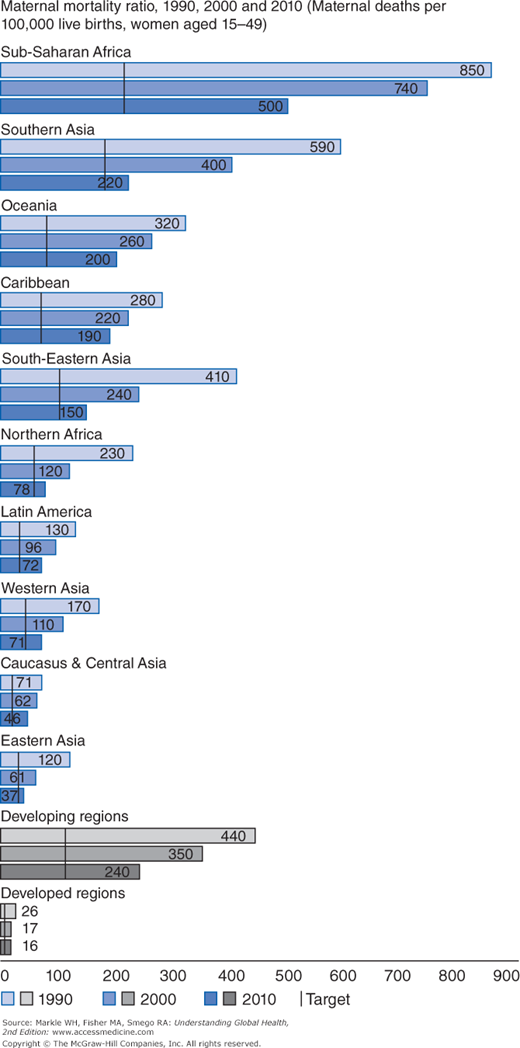

There continues to be a large disparity in MCH indicators between high- and low-income countries. The highest levels of mother and child health can be found in European and higher income countries in Asia. These are also countries that provide high-quality and accessible health and social services. Infant mortality rates (IMR) of less than 4/1,000 are found in Singapore, Iceland, Japan, Sweden, Finland, and Norway, and maternal mortality rates (MMRs) less than 5/100,000 can be found in Estonia, Greece, Singapore, Italy, Austria, and Sweden. Although there has been great improvement in MCH indicators in low income countries in the last 10 years, the rates remain much higher. In 2000, 18 countries had MMRs higher than 1,000/100,000, but there were only 2 in 2010. These were 1,100/100,000 in Chad and 1,000/100,000 in Somalia. Sierra Leone, which had the highest rate in 2000 (2000/100,000), was reduced to 890 by 2010. There were eight other countries with very high MMRs (above 600)—all in sub-Saharan Africa (Sierra Leone, Central African Republic Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, the Sudan, Cameroon, and Nigeria).2,3 Most of the countries with the highest mortality rates are also those experiencing war and conflict. Almost all (99%) of maternal deaths occur in low-income countries. The regions with the highest maternal deaths are Africa and the poorer parts of Asia (Table 4-1).2 Two countries, India and Nigeria, account for a third of global maternal deaths.2 Infant mortality disparities show the same trend, although not to the same extreme level. The highest infant mortality rates (IMRs) are found in the same countries with high maternal mortality, with the highest reported in 2011 in Sierra Leone at 119/1,000—which was a significant reduction from 2003 when the IMR was 166. Four countries (Sierra Leone, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic) had IMRs higher than 100/1,000, compared with 24 in 2003. Twenty-one countries had rates higher than 70/1,000.4,5

1990a | 2010a | % change in MMR between 1990 and 2010a | Average annual % change in MMR between 1990 and 2010a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Region | MMR | Maternal deaths | MMR | Maternal deaths | ||

World | 400 | 543,000 | 210 | 287,000 | –47 | –3.1 |

Developed regions | 26 | 4,000 | 16 | 2,200 | –39 | –2.5 |

Developing regions | 440 | 539,000 | 240 | 284,000 | –47 | –3.1 |

Northern Africa | 230 | 8,500 | 78 | 2,800 | –66 | –5.3 |

Sub-Saharan Africa | 850 | 192,000 | 500 | 162,000 | –41 | –2.6 |

Eastern Asia | 120 | 30,000 | 37 | 6,400 | –69 | –5.7 |

Eastern Asia excluding China | 53 | 610 | 45 | 400 | –15 | –0.8 |

Southern Asia | 590 | 233,000 | 220 | 83,000 | –64 | –4.9 |

Southern Asia excluding India | 590 | 70,000 | 240 | 28,000 | –59 | –4.4 |

Southeast Asia | 410 | 50,000 | 150 | 17,000 | –63 | –4.9 |

Western Asia | 170 | 7,000 | 71 | 3,500 | –57 | –4.2 |

Caucasus and Central Asia | 71 | 1,400 | 46 | 740 | –35 | –2.1 |

Latin America and the Caribbean | 140 | 16,000 | 80 | 8,800 | –41 | –2.6 |

Latin America | 130 | 14,000 | 72 | 7,400 | –43 | –2.8 |

Caribbean | 280 | 2,300 | 190 | 1,400 | –30 | –1.8 |

Oceania | 320 | 620 | 200 | 510 | –38 | –2.4 |

The means to improve MCH outcomes have been well demonstrated in high-income countries. It is not just a matter of technology; the health of mothers and children is inexorably linked to women’s status and education, and the general socioeconomic well-being of communities. This chapter explores some of the reasons for the disparities that exist between developed and developing regions, and it examines some of the emerging women’s health issues. It provides an emphasis on interventions that have made a difference.

A Basic Primer of Maternal and Child Health Indicators and Terms

Prior to an exploration of the issues, it is important to have a basic understanding of some of the terms and indicators used in maternal and child health.

- Maternal mortality rate: The number of maternal deaths per 100,000 births. The formal definition of maternal mortality is death while pregnant or within 42 days of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of the duration or site of the pregnancy. Death may be from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

- Infant mortality rate: The number of infant deaths per 1,000 births. This is defined as a death of a child from birth up to 1 year of age.

- Perinatal mortality rate (PNMR): The number of perinatal deaths per 1,000 births. Perinatal deaths are defined as occurring during late pregnancy (at 22 completed weeks of gestation and over), during childbirth, and for up to 7 completed days of life.

- Neonatal mortality rate (NMR): The number of deaths during the first month of life per 1,000 births.

- Postneonatal mortality rate (PNNMR): The number of postnatal deaths (1 month through 12 months) per 1,000 births.

- Child mortality rate (CMR): The number of deaths among children younger than 5 years per 1,000 births. This is also referenced as the under-5 mortality rate (U5MR).

- Preterm birth: Birth at gestational age of less than 37 weeks.

- Low birth weight (LBW): Less than 2,500 grams, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO); may be due to preterm delivery or smallness for gestational age (intrauterine growth retardation), or to a combination of both.

- Very low birth weight (VLBW): Less than 1,500 grams; these infants are too small and physiologically undeveloped to survive in most developing countries.

- Total fertility rate (TFR): The number of children that would be born to each woman if she was to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children at each age at the same rate as the existing age-specific fertility rate. TFR is used to estimate population growth rates.

- Contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR): The percentage of married women of reproductive age (15 to 49) who are using or whose partners are using contraception.

- Traditional birth attendant (TBA): A person who assists the mother during childbirth and delivery. This person, who may be male or female, depending on the country and culture, is usually trained through apprenticeship. A trained TBA refers to a TBA who has had some formal training in hygienic delivery, often through the provision of WHO birthing kits.

- Skilled birth attendance: Delivery by a nurse, nurse midwife, or doctor who is licensed to practice and has undergone specific training.

A warning about mortality and morbidity data: Measurement issues are often a problem; many countries’ vital statistics are not reliable or consistently collected. In these situations, there are two approaches to estimating mortality: very large sample sizes and interviews to determine maternal or child deaths; and methods that use smaller sample sizes, such as the Sisterhood Method that was developed in the 1980s for MMR estimation. The Sisterhood Method inquires about deaths of sisters in pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum and has been used in many parts of the world to provide data.6 If mortality data are difficult to determine, obviously morbidity data are even less reliable.

Historical Perspective

MCH has always been used as an indicator of the overall health of a society. MCH really began to improve around the beginning of the 20th century in developed countries when general public health improvements reduced the spread of infectious diseases and economic development increased access to food and better housing. This overview focuses on the period after World War II when global efforts were initiated after the founding of the United Nations (UN).

Prior to World War II, the health care systems of developed and developing countries were more or less similar. A gradual increase in the standard of living among developed countries led to the betterment of health services, including those that revolved around MCH. After World War II, the health care systems of many developing countries emphasized tertiary care, modeled after the systems that existed in industrialized nations. This resulted in increasing medical specialization and a hierarchy in health care systems in which most of the resources went to tertiary care and technology. The major emphasis for international development agencies during this time was on the eradication of specific diseases such as smallpox, TB, and malaria. Although there were some successes with this approach, it did not do much to improve health care access at the community level, and MCH health indicators did not greatly improve. Furthermore, the overall disease burden of the poor was not being addressed. The limitations of vertical disease programs were eventually recognized. In 1978, the Declaration of Alma-Ata established the importance of a holistic approach to health (complete physical, mental, and social well-being) and identified the role of economic and social development, and individual and government responsibility. Primary health care was proposed as the means to reach the goal of Health for All by 2000.7 Unfortunately, this laudable goal was not accomplished, but the striving continues.

Many global initiatives have focused on MCH issues: White Ribbon Alliance, Saving Newborn Lives, Family Care International, The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Women Deliver, The Global Campaign for the Health Millennium Development Goals, and Saving Newborn Lives, to mention just a few. This also includes maternal, newborn, and child health streams within larger initiatives such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Early Age at Marriage

A woman’s age at first marriage is an important indicator of her social, educational, and economic status and has significant implications for her reproductive health, specifically with respect to childbearing. Pregnancy and childbirth closely follow the start of marriage. In many developing countries, between 50% and 75% of all births to married women occur less than 2 years after women enter their first union.8 Early marriage, therefore, coincides with childbearing at a young age. Early pregnancy creates a number of health risks for a young woman and her infant, if she carries the pregnancy to term. Moreover, for women who marry young, motherhood limits opportunities for education, employment, and personal growth. Early age at first marriage is often associated with a higher probability of divorce and separation. With the dissolution of marriage, women face economic and social challenges because they either assume full responsibility for dependent family members or are expelled from the family of origin as well as their family of marriage, leaving them without support.

Although the situation varies greatly by country and region, marriage during the teenage years is common in developing countries with 20% to 50% of women marrying or entering a union by age 18, and 40% to 70% doing so by age 20.8 Singh and colleagues have done extensive work on early marriage and provide the data for the information in the rest of this paragraph. Women are most likely to marry at a young age in sub-Saharan Africa where 60% to 92% of all women ages 20 to 24 had entered their first union by age 20. A high prevalence of early marriage was also found in a few countries in other regions. In Bangladesh, Guatemala, India, and Yemen, 60% to 82% of all women 20 to 24 had married by age 20. Compared with sub-Saharan Africa, marriage during teenage years is less common in Latin America, Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East. About 20% to 33% of 20- to 24-year-olds in those regions had entered their first marriage by age 18, and 33% to 50% had married by age 20. Even in France and the United States, 11% of all 20- to 24-year-olds were married or cohabiting by age 18, and 32% of these by age 20. The only exception to such high rates of marriage during adolescence can be found in Japan, where only 2% of 20- to 24-year-olds had married by age 20.8

The data clearly indicates that there are variations in the timing of marriage within and between regions. There are three factors, however, that are thought to be closely correlated and relevant to a woman’s age at first marriage: women’s acquisition of formal education, their participation in the labor force, and urbanization. Exposure to formal schooling helps shape values and ideas, often resulting in the adoption of Western values and behavior. Additionally, exposure to and attainment of education often leads to better jobs and higher wages, which, in turn, increases economic stability and reduces motivation for early marriage. With access to higher education and with knowledge in areas such as reproduction, women often have an increased ability to regulate their own fertility.

Another key variable relevant to a woman’s age at first marriage is her participation in the formal work sector. A woman’s participation in the formal work sector often exposes her to new ideas and norms that discourage early marriage. Economic stability and/or independence as a result of participation in the labor force may enhance a woman’s ability to postpone marriage. There is an economic incentive for parents to encourage their daughters to remain single and continue work. Therefore, the family pressure to get married often subsides or disappears.

Urbanization is the third factor that influences a woman’s age at first marriage. Research shows that there are significant differences in the age at marriage between women who live in urban settings compared with those who live in rural settings. Women living in urban areas marry at a later age. Possible explanations for this include a sense of independence gained from greater access to the labor force, increased accessibility to higher education, distance from community- and kinship-based social control, and exposure to modern values and beliefs.

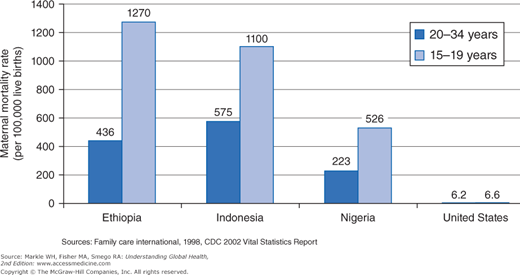

Child marriage is used to describe a legal or customary union between two people, of whom one or both of the spouses are under the age of 18.9 Child marriage curtails educational opportunities and impacts the social development of young girls. Because it affects girls in greater numbers and with graver consequences compared with boys, child marriage brings additional dimensions that further exacerbate the health status of women. In addition to the lack of access to information regarding basic reproductive health issues, the social isolation, limited social support, and powerlessness pose greater reproductive health risks. Lack of autonomy in movement and decision making among young wives can aggravate the risks of maternal mortality and morbidity for pregnant adolescents who already face high-risk pregnancies. There is a strong correlation between the age of the mother and maternal mortality and morbidity. Girls ages 10 to 14 are five times more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth than women ages 20 to 24.10 Girls ages 15 to 19 are twice as likely to die (Figure 4-1).10 In addition, girls who have children before their bodies are fully developed are at greater risk for obstetric fistula, a debilitating medical condition often caused by prolonged or obstructed labor. The ability to negotiate sexual relations, contraception, and childbearing, as well as other aspects of domestic life, diminishes as the age of first marriage decreases. Vulnerability to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections also increases with the lack of ability to negotiate condom use with an older, sexually experienced partner. Women who marry at a younger age are more likely to be victims of domestic violence, and more likely to believe that the violence is justified.10

Although most countries have declared 18 as the minimum legal age of marriage, in a few developing countries, marriage before age 18 remains common. Child marriages remain common in rural areas and among groups with the least economic resources. For the years 2000 to 2011, just over a third of women ages 20 to 24 years in developing regions were married or in union before their 18th birthday, equivalent to approximately 67 million women in 2010. About 12% of them were married or in union before age 15. The prevalence of child marriage varies substantially among countries, ranging from only 2% in Algeria to 75% in Niger. In 41 countries, 30% or more of women ages 20 to 24 were married or in union when they were still children.9 Child marriage is most common in South Asia and in West and Central Africa, where two of five girls marry or enter into union before age 18 (46% and 41%, respectively). Over the last 10 years, child marriage at the global level has remained relatively constant (about 50% in rural areas and 23% in urban areas).9 If current trends continue, by 2030 the number of child brides marrying each year will have grown 14% since 2010, from 14.2 to 15.1 million.9

A number of factors perpetuate the practice of child marriage. Risk factors such as poverty and low levels of education are directly correlated with higher rates of child marriage. In parts of Africa and Asia, marriage of children is valued as a means of consolidating powerful relations between families, for sealing deals over land or other property, or even for settling disputes or feuds between families or clans.11 Child marriage may also be valued as an economic coping strategy to reduce the costs of raising daughters. The economic benefits of bride price (money, livestock, or property given to the bride’s family by the groom’s family) may act as further motivation for child marriage in regions of sub-Saharan Africa. In many regions around the world, child marriage is traditionally recognized as necessary for controlling girls’ sexuality and reproduction. Social, traditional, and cultural norms around child marriages often lead to pressure on families to conform. Lastly, the desire to secure the future of a girl child in situations of insecurity and acute poverty, particularly during disasters such as war and famine, contribute further to the practice of child marriage.11

Approaches to address and eventually eliminate child marriages include increasing education and income, creating safe spaces, and reducing isolation of girls/women. Using social media and behavior change techniques to empower girls by helping them understand their rights, providing access to family planning and reproductive health knowledge and services, and working within communities to change attitudes and behaviors are also promising approaches.

Women’s Empowerment and Education

The UN has identified five components of women’s empowerment: (1) the sense of self-worth; (2) the right to have and to determine choices; (3) the right to have access to opportunities and resources; (4) the right to have the power to control their own lives, both within and outside the home; and (5) the ability to influence the direction of social change to create a more just social and economic order, nationally and internationally.12

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) focuses on gender equality and women’s empowerment not only as human rights, but also because they are a pathway to achieving the MDGs and sustainable development.13 The nature of empowerment renders it difficult to define. It is often referred to as a goal for development programs/projects, but it is also an individual development process that contributes to the attainment of rights identified by the UN. Empowerment is a complex issue with varying interpretations in different societal, national, and cultural contexts. Indicators have been developed for societal, community, family and individual levels. Indicators for family and individual levels include participation in crucial decision-making processes; women’s control of their reproductive functions and decisions on family size; women’s control of expenditures of their own incomes; a sense of pride and value in their work; building self-confidence and self-esteem; the ability to prevent violence; and men’s participation in domestic work.

“Education is one of the most important means of empowering women with the knowledge, skills and self-confidence necessary to participate fully in the development process.”14 Education is important for everyone, but especially for girls and women. As discussed earlier, education and early marriage are closely related. But there are many health and economic factors that are influenced by women’s education.

Women’s education has been associated with better health outcomes for mothers and children, delayed age at marriage, and increased family income. In terms of women’s health, increasing levels of women’s education has been related to reductions in maternal mortality. Women ages 25 to 44 in sub-Saharan Africa showed an increase in education from 1.5 years in 1980 to 4.4 in 2008 and concomitant declines in MMR.15 Other studies have shown the relationship between lower levels of maternal education and higher maternal mortality exists even among women who are able to access facilities providing intrapartum care. In a 2004-2005 study of 287,000 women giving birth in facilities in 24 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the risk of maternal mortality was greatest for women with no education (2.7 times higher). Those with between 1 and 6 years of education had twice the risk of maternal mortality compared with women with more than 12 years of education.16,17 Gender inequality also contributes to a woman’s risk of acquiring HIV. Nearly half of those living with the virus worldwide are women, and women’s subordination to men not only increases their risk of infection but also limits access to treatment.18 In many parts of the world a woman’s greatest risk for HIV is being married.

The UNESCO 2011 Report, “Education Counts: Towards the Millennium Development Goals,”19 clearly documents the many benefits of girls’ and women’s education. Higher levels of women’s education have been associated with:

- Lower fertility rates, increased facility deliveries, better birth spacing, and higher levels of prenatal care.

- Greater knowledge about HIV and higher utilization of retrovirals when HIV positive.

- Lower IMRs and CMRs, higher rates of vaccination, and less stunting from malnutrition.

- Reduced poverty; each additional year of schooling can increase income by 10%.

Education and empowerment are strongly linked to women’s and children’s health, and they are mutually reinforcing. Children of mothers with higher education are more likely to complete school. Educated mothers are more likely to be aware of the benefits of schooling and to contribute to the costs of schooling through their participation in the labor force.20

Improving women’s education, workforce participation, and social and political opportunities are crucial to strengthening their health.21 It is generally believed that women’s lack of decision-making power may restrict their use of modern contraceptives. In a study using Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data from Namibia, Zambia, Ghana, and Uganda, positive associations were found between the overall empowerment score and contraception use.22

Although some studies have shown that domestic violence against women is negatively associated with the educational level, this is not universally true. Educational discrepancies between spouses may also play a role. In a recent study in India and Bangladesh, wives with higher education than their husbands were less likely to experience violence compared with when both spouses had lower education. Equally high-educated couples revealed the lowest likelihood of experiencing violence.23 Another study in Egypt found that higher levels of education had a 28-fold positive effect in improving women’s lives and empowerment. Uneducated women were five times more likely to be exposed to violence. Uneducated husbands were four times more likely to hurt their wives.24 An older study in Finland suggested that life expectancy as well as disability-free life expectancy showed a direct relationship with level of education: the higher the level of education, the higher the life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy.25

Overview of Major Women’s and Children’s Health Issues

This section addresses the major problems in women’s and children’s health. It presents information about epidemiology, causation, health care delivery, and basic treatment and interventions. These topics are organized around a life cycle approach that begins with family planning and ends with old age. The major issues that affect both maternal and child health are anemia, pregnancy, childbirth, and perinatal, infant, child, and adolescent health.

Reproductive choice is a basic human right. The aim of family planning programs is to enable individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children, to have the information and means to do so, to make informed choices, and to choose from a full range of safe and effective methods of contraception.26 However, access to relevant information and high-quality services is limited in many regions of the world. Most family planning programs have been targeted at women; therefore, this section concentrates on them.

During the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, 180 nations adopted a program of action that included, among its major goals, improving reproductive health and making family planning services universally available.26

Women between the ages of 15 and 49 years are considered to be women of reproductive age (WRA), and this group is the population base used to estimate need and utilization of family planning. In 2012, there were an estimated 1.5 billion WRA. Of these, 645 million were using modern contraceptive methods. This represents a 42% increase from 2008. However, the unmet need increased in most of Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. There are 220 million women, mostly in developing countries and the former Soviet republics, who are not using contraception in spite of an expressed desire to space or limit the numbers of their births.27 These women are considered to have an “unmet need for family planning.”

Before examining the global estimates as well as the impact of unmet need on MCH, it is important to understand how the unmet need for family planning is estimated. It has conventionally been estimated from representative population-based surveys of currently married women as the sum of currently pregnant women who report that their pregnancy was unintended (those who wish to limit their births) and the number of currently nonpregnant women who are not using contraception and would not like to have any more children or none in the next 2 years (those who wish to space their births).28 This method to estimate unmet need has been criticized because it is thought to underestimate the actual numbers. Furthermore, it excludes both currently married women who are not pregnant and who are using ineffective or unsatisfactory methods of contraception and sexually active women who are not currently married and who do not wish to become pregnant, at least in the next 2 years.

The debate about expanding the definition of unmet need continues. Ross and Winfrey used an expanded definition to offer an updated estimate of unmet need in the developing world and the former Soviet republics.29 Under their definition, the group includes all fecund women, married or living in union, who are not using any method of contraception and who either do not want to have any more children or who want to postpone their next birth for at least 2 more years. The group also includes all pregnant married women and women who have recently given birth and are still amenorrheic. They are included if their pregnancies or births were unwanted or mistimed because they were not using contraception. This approach may still underestimate the number of women with unmet need because the group does not include users of traditional methods who may have an unmet need for modern methods. Their inclusion would result in considerably larger estimates, especially in regions where the use of traditional methods is popular.

Table 4-2 shows the number and percentage of women with an unmet need for contraception in various regions and the changes between 2008 and 2012.27 The number of women in the reproductive-age group varies by region, with 63% of the total for the developing world in Asia, which contains 140 million WRA with unmet need. It is important to keep in mind that Asia contains several countries with very large populations (India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). Sub-Saharan Africa contains 53 million WRA with unmet need (26% of the total). Latin America contributes 23 million WRA with unmet need (10%), nearly half of whom live in Mexico and Brazil. The 69 poorest countries in the world have 162 million women with unmet need (73% of the total), which suggests that unmet need will continue to have a major impact on population growth in those countries.

| Region and subregion | Women ages 15 to 49 with unmet need for modern methods, millions | % of women ages 15 to 49 in need of contraception who have unmet need for modern methods | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2012 | Annual % change | 2008 | 2012 | Annual % change | |

| Developing world | 226 | 222 | –0.5 | 27 | 26 | –1.5 |

| Africa | 55 | 58 | 1.6 | 54 | 53 | –0.5 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa* | 50 | 53 | 1.6 | 62 | 60 | –0.9 |

| Eastern Africa | 19 | 20 | 0.4 | 63 | 54 | –3.5 |

| Middle Africa | 10 | 10 | 1.3 | 82 | 81 | –0.1 |

| Southern Africa | 2 | 2 | –6.2 | 25 | 17 | –8.1 |

| Western Africa | 18 | 19 | 2.6 | 74 | 74 | 0.0 |

| Northern Africa | 6 | 8 | 5.8 | 25 | 32 | 7.8 |

| Asia | 147 | 140 | –1.1 | 23 | 21 | –1.9 |

| Eastern Asia | 24 | 16 | –7.8 | 8 | 6 | –7.7 |

| Central Asia | 3 | 2 | –3.1 | 30 | 28 | –1.4 |

| South Asia | 79 | 83 | 1.1 | 34 | 34 | –0.4 |

| Southeast Asia | 25 | 25 | –0.6 | 33 | 28 | –4.2 |

| Western Asia | 15 | 14 | –2.8 | 54 | 50 | –1.8 |

| Oceania | <1 | 1 | 2.1 | 39 | 49 | 6.8 |

| Latin America | 24 | 23 | –1.4 | 25 | 22 | –2.8 |

| Caribbean | 2 | 2 | –2.4 | 31 | 30 | –0.8 |

| Central America | 5 | 5 | 1.3 | 23 | 23 | 0.0 |

| South America | 17 | 16 | –2.0 | 25 | 21 | –3.8 |

| 69 poorest countries | 153 | 162 | 1.5 | 40 | 39 | –0.6 |

Regional variations in the prevalence among women who wish to space or limit births are evident. Ross and Winfrey found that in sub-Saharan Africa, 65% of unmet need is for spacing, in contrast to Latin America, where it is only 42%. In other regions, such as Asia, spacing and limiting needs are nearly equal. Unmarried women add to unmet need, accounting for 7% of the developing world total.29 The proportion of unmarried women who are sexually active varies by region, ranging from 4% in Asia to 16% in sub-Saharan Africa. These differences in demand affect the kinds of contraceptive supplies needed as well as budgetary allocations.

A number of proven benefits are associated with family planning including maternal health, child survival, gender equality, and HIV prevention. Additionally, family planning can improve family well-being, raise female economic productivity, and lower fertility, thereby reducing poverty and promoting economic growth.26 Despite these outcomes, the unmet need for family planning still persists. The causes for this include lack of accessible services; shortages of equipment, commodities, and personnel; lack of method choices appropriate to the situation of the woman and her family; lack of knowledge about the safety, effectiveness, and availability of choices; lack of community or spousal support (social opposition); misinformation and rumors; health concerns about possible side effects; and financial constraints.26,30

A number of social, cultural, and gender-related obstacles can prevent a woman from realizing her childbearing preferences. At the policy level, for example, decision makers may not place high priority on funding contraceptive services because they view them as “women’s programs.” Laws may require the woman to seek her husband’s approval to use some methods. At the health facilities level, service providers’ bias may limit options for contraception. At the community level, contraceptives may be considered as contributing to female promiscuity. Furthermore, men often have a greater decision-making power to determine family size. Social norms regarding fertility and virility, and the overall low status of women, keep many women and men from seeking family planning.31

Over the years, the WHO and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have made varying recommendations on birth spacing. These recommendations, which have traditionally been based on pregnancy outcomes, have caused confusion due to the differences in the time interval recommended between births by each agency. A 2006 WHO report, supported by USAID, recommends an interval of at least 24 months following a live birth to the next pregnancy to reduce the risk of adverse maternal, perinatal, and infant outcomes. An interval of at least 6 months to the next pregnancy is recommended following a miscarriage or induced abortion.32

The unmet need for spacing has multiple consequences on MCH. First, maternal depletion, defined as a broad pattern of maternal malnutrition resulting from the combined effects of dietary inadequacy, heavy workloads, and energy costs of repeated pregnancy, can result in increased maternal morbidity and mortality. There is, however, limited empirical evidence to support the theory of maternal depletion. The consequences for infants born after a short birth interval can include poor intrauterine growth and an increased risk of preterm birth.33 Second, close birth spacing may further burden already limited family resources. Third, a child born after a short birth interval can also suffer from nutritional deficits as the mother interrupts breastfeeding to focus on the newborn. Fourth, the likelihood of transmission of infectious diseases is increased as a result of overcrowding and the presence of children of similar ages.

As with the unmet need for spacing, a number of consequences are associated with the unmet need to limit births. The WHO estimates that approximately 38% of all pregnancies occurring around the world every year are unintended. In 2012, an estimated 80 million unintended pregnancies occurred in the developing world due to contraceptive failure and nonuse among women with unmet need. About 6 of 10 such unplanned pregnancies result in induced abortion. Unintended pregnancies increase the lifetime risk of maternal mortality. They can also lead to unsafe abortion, poor infant health, and lower investment in the child. The prevention benefits of contraception are well documented. In 2012, modern contraception prevented 218 million unintended pregnancies, 55 million unplanned births, 138 million induced abortions (40 million of which were unsafe), 25 million miscarriages, 118 million maternal deaths, 1.1 million neonatal deaths, and 700,000 neonatal deaths.27

Anemia is a global public health problem. It is the decreased ability of red blood cells to provide adequate oxygen to body tissues and is characterized by a hemoglobin (Hb) concentration below the established cut-off levels (Table 4-3). Hb is the oxygen-carrying molecule of red blood cells. Anemia affects both developing and developed countries with the greatest burden felt in resource-poor areas where significant proportions of young children and women of childbearing age are assumed to be anemic. In 2002, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was considered to be among the most important contributing factors to global burden of disease.34

Age or gender group | Hemoglobin below,g/dl | Hematocrit below,% |

|---|---|---|

Children, 0.50–4.99 years | 11.0 | 33 |

Children, 5–11.99 years | 11.5 | 34 |

Children,12–14.99 years | 12.0 | 36 |

Nonpregnant women, ≥15.00 years | 12.0 | 36 |

Pregnant women | 11.0 | 33 |

Men, ≥15.00 years | 13.0 | 39 |

It is important to differentiate between anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia (Box 4-1).35 Dietary iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia; however, it is not the sole contributor. Factors that lower blood Hb concentrations, such as heavy blood loss due to menstruation or parasitic infections, are among other causes of anemia. Acute or chronic infections, such as malaria, cancer, TB, and HIV, can also lower blood Hb concentrations. In fact, anemia is recognized as an independent risk factor for early death among HIV/AIDS-infected individuals.36 Micronutrient deficiencies, other than iron, including vitamins A, B12, folate, riboflavin, and copper, can increase the risk of anemia. Within some populations, the impact of hemoglobinopathies on anemia also needs to be considered.

Anemia: Abnormally low hemoglobin level due to pathologic condition(s). Iron deficiency is one of the most common, but not the only cause of anemia. Other causes of anemia include chronic infections, particularly malaria, hereditary hemoglobinopathies, and other micronutrient deficiencies, particularly folic acid deficiency. It is worth noting that multiple causes of anemia can coexist in an individual or in a population and contribute to the severity of the anemia. Iron deficiency: Functional tissue iron deficiency and the absence of iron stores with or without anemia. Iron deficiency is defined by abnormal iron biochemistry with or without the presence of anemia. Iron deficiency is usually the result of inadequate bioavailable dietary iron, increased iron requirement during a period of rapid growth (pregnancy and infancy), and/or increased blood loss such as gastrointestinal bleeding due to hookworm or urinary blood loss due to schistosomiasis. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Iron deficiency, when sufficiently severe, causes anemia. Although some functional consequences may be observed in individuals who have iron deficiency without anemia, cognitive impairment, decreased physical capacity, and reduced immunity are commonly associated with iron deficiency anemia. In severe iron deficiency anemia, capacity to maintain body temperature may also be reduced. Severe anemia is also life threatening. Source: Yip R, Lynch S. Iron Deficiency Anemia Technical Consultation. New York: UNICEF, October 1998. |

Measuring Hb concentration is the most reliable, easy, and inexpensive way to assess anemia. Estimates of prevalence rates of IDA often use rates of anemia as a proxy because Hb concentration is relatively easy to determine. However, because anemia can be caused by factors other than iron deficiency, the etiology of anemia should be interpreted with caution if the only indicator used is Hb concentration.

The WHO estimates that anemia affects 1.6 billion people globally, almost one-fourth of the world’s population, and that approximately 50% of all cases can be attributed to iron deficiency.37 Globally, the highest prevalence of anemia is found among preschool-age children (47.4%) and the lowest prevalence among men (12.7%); global prevalence among men is based on regression-based estimates because limited data are available for this population group (Table 4-4). Nonpregnant women represent the population group with the greatest number of individuals affected, although the prevalence rate is lower among this group compared with pregnant women.37 Regional estimates for preschool-age children and pregnant and nonpregnant women by the WHO, based on a systematic review of all data collected and published between 1993 and 2005, indicate that the highest proportion of individuals affected are in Africa (44% to 64%) (Table 4-5). The greatest number affected are in Asia where 520 million individuals in these three population groups are affected:37 60% of all anemic preschool-age children and pregnant women, and 70% of all anemic nonpregnant women.

Prevalence of anemia | Population affected | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Population group | % | 95% CI | Number, millions | 95% CI |

Preschool-age children | 47.4 | 45.7–49.1 | 293 | 283–303 |

School-age children* | 25.4 | 19.9–30.9 | 305 | 238–371 |

Pregnant women | 41.8 | 39.9–43.8 | 56 | 54–59 |

Nonpregnant women | 30.2 | 28.7–31.6 | 468 | 446–491 |

Men* | 12.7 | 8.6–16.9 | 260 | 175–345 |

Elderly* | 23.9 | 18.3–29.4 | 164 | 126–202 |

Total population | 24.8 | 22.9–26.7 | 1620 | 1500–1740 |

Preschool-age childrenb | Pregnant womenb | Nonpregnant womenb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

UN regiona | Prevalence, % | No. affected, millions | Prevalence, % | No. affected, millions | Prevalence, % | No. affected, millions |

Africa | 64.6 | 93.2 | 55.8 | 19.3 | 44.4 | 82.9 |

Asia | 47.7 | 170.0 | 41.6 | 31.7 | 33.0 | 318.3 |

Europe | 16.7 | 6.1 | 18.7 | 1.4 | 15.2 | 26.6 |

LAC | 39.5 | 22.3 | 31.1 | 3.6 | 23.5 | 33.0 |

NA | 3.4 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 0.3 | 7.6 | 6.0 |

Oceania | 28.0 | 0.7 | 30.4 | 0.2 | 20.2 | 1.5 |

Global | 47.4 | 293.1 | 41.8 | 56.4 | 30.2 | 468.4 |

The main cause of anemia in developed countries is iron deficiency. However, in developing countries, factors such as malaria and parasitic infections often play a role. Anemia rates are further impacted, especially in developing countries, by consequences of low socioeconomic status such as lack of food security, inadequate or lack of access to health care, and poor environmental sanitation and personal hygiene.

The consequences of IDA in the general population include increased morbidity from infectious diseases because anemia adversely affects the immune system. It also reduces the body’s ability to monitor and regulate body temperature when exposed to cold. Additionally, cognitive performance is impaired at all stages of life, and physical work capacity is significantly reduced as a result of iron deficiency.

Women, in particular, are at risk of anemia due to periodic menstrual blood loss and an increased need for iron during pregnancy.38–40 Anemia affects approximately 42% (over 56 million) of the pregnant women in the world.41 IDA during pregnancy has serious clinical consequences. It is associated with multiple adverse outcomes for both mother and infant, including intrauterine growth retardation, an increased risk of hemorrhage, sepsis, maternal, infant, and perinatal mortality, increased stillbirths, low birth weight, and prematurity. Forty percent of all maternal perinatal deaths are linked to anemia.42 Favorable pregnancy outcomes occur 30% to 45% less often in anemic mothers, and their infants have less than half of normal iron reserves.42 Pregnant women who are severely anemic are less able to withstand blood loss and may require transfusions. The availability and safety of blood poses a dilemma in poorer countries, which usually have a higher prevalence and a more complex etiology of anemia.

Long-term health consequences, such as the development of chronic noncommunicable diseases in adulthood (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cancer), have been linked to early nutritional deficiencies and intrauterine growth retardation among infants born to mothers with anemia.43 Furthermore, infants who become anemic may experience permanent impairment of cognitive development. Lower cognitive test scores have been observed in young children with anemia. These outcomes do not improve when anemia is corrected or as development continues.

A range of strategies are used to control and prevent anemia. Increasing awareness and knowledge among health care providers and the general public concerning the health risks associated with anemia is a key strategy. Additional strategies include food-based approaches, food fortification, and iron supplementation. These strategies may not be feasible or sustainable, especially in low-resource settings, where challenges such as food security and low social status of women are still problems.

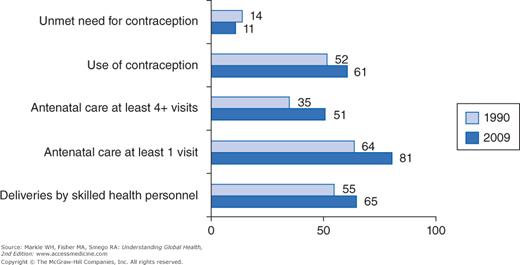

Pregnancy and childbirth are a natural part of the human life cycle. However, pregnancy and delivery can be very dangerous for women who have complications and do not have access to emergency care. Delivery and the immediate newborn period is a similarly dangerous time for infants. Two factors that play major roles in both maternal and neonatal birth outcomes are where and by whom a woman is delivered. Whereas hospital deliveries with a doctor in attendance is the norm for high-income countries, most women, especially in the lowest income countries, deliver at home with assistance from unskilled caregivers. Meeting MDG 5 requires improving many indicators, as shown in Figure 4-2.

The relationship between early and frequent provision of prenatal care and better MCH outcomes has been documented but is subject to ongoing review regarding the number and content of visits.44

The WHO recommends a minimum of four antenatal visits with skilled health professionals (nurses, nurse midwives, or doctors) and that the basic minimum services should include measurement of blood pressure, blood tests for syphilis and anemia, and urine testing for bacteriuria and proteinuria.45 The purpose of these visits is to provide early access to health care with immunization, maternal monitoring, screening, treatment, and referral. Early and more frequent contact with health care provides the opportunity to increase health knowledge and improve health behaviors, as well as access to the following services:

- Maternal monitoring, including nutrition and weight, and the identification and treatment of other problems such as anemia and hypertension. In some programs prenatal care includes food supplements.

- Screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV, and giving HIV-positive pregnant women antiretroviral treatment to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

- Treatment of malaria, TB, and other diseases that may cause problems for a pregnant woman and her fetus.

Prenatal care can identify women at high risk based on their obstetric history, complications, and general health status. It is important to note that approximately 40% of all pregnant women experience some type of complication, and 15% have a serious problem requiring immediate obstetric attention.46 In most cases the risks cannot be adequately predicted, which requires that all women receive skilled care to prevent maternal and neonatal deaths. In 2010, only 55% of women in developing regions had the recommended four prenatal visits.1

Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) are usually apprenticed with an experienced TBA to learn the skills of delivering babies. In some countries, training in more sanitary delivery techniques, such as the use of new razors, and in the recognition of danger signs and when to refer, has been provided to TBAs, who are then called trained TBAs. The WHO has provided home delivery kits (soap, new razors, gauze, and other materials) to many programs that work with TBAs. These kits can also be assembled locally. TBAs provide accessible community-based care that incorporates local beliefs and traditions. Many women prefer to deliver at home with their family, where they can follow traditional practices regarding care of the mother and baby and the disposition of the placenta.

TBAs typically do not provide prenatal care, although this has been incorporated in TBA training so that they can identify women at risk. However, there has been considerable controversy about the role of TBAs and whether it is possible to improve maternal and prenatal outcomes during home deliveries by TBAs.47–49 A major issue is that even trained TBAs observing best practices are unable to refer and transport mothers and babies to higher-level care when emergencies occur.50

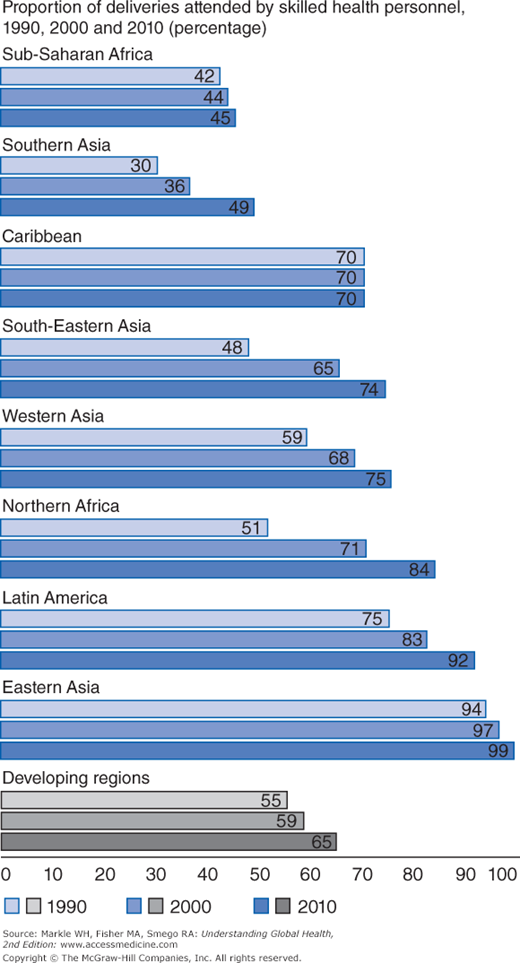

As a result, the WHO recommends that women be delivered by skilled health personnel (an accredited health professional, nurse midwife, doctor, or nurse who has been educated and trained to manage normal pregnancies and deliveries and to refer complications). These goals were incorporated in the MDGs, which set the objective of 80% of all births assisted by skilled attendants by 2005; however, this goal has not been reached, nor is it likely that the goal of 95% will be reached by 2015 (see Figure 4-3).1

Currently, 65% of women in developing countries deliver with skilled attendance, but this does not reflect the situation in countries such as Haiti or regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, where 80% to 90% of deliveries occur at home with TBAs. The MDGs also set the goal of reducing maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015. Although maternal mortality was reduced by 47%, as of 2010 the MMR for developing regions was 240/100,000 and seems unlikely to reach the target by 2015.1

Related to the issue of home delivery by TBAs is access to primary care and hospital services. Prenatal care, especially tetanus immunization and iron supplementation, has been demonstrated to improve pregnancy outcomes, but it requires that women have access to basic primary care services. As noted earlier, the recommendation is that women have a minimum of four prenatal visits. At least 27% of women in developing countries receive no antenatal care during pregnancy, and 35% give birth without a skilled attendant.1 Less information is available about postpartum care, which is important for mothers and newborns. It has been estimated that 42% of maternal deaths, 32% of stillbirths, and 23% of neonatal deaths occur in the period between birth and the period immediately following birth. Most women and babies do not receive postpartum care, and this is especially true of those without skilled attendance at delivery.51 This lack of care is most life threatening during childbirth and the days immediately after delivery because these are the times when sudden life-threatening complications are most likely to arise. WHO recommendations call for mothers and infants to be seen within 72 hours of delivery, but recent data from the 47 countries of sub-Saharan Africa shows that only 51% of them track postnatal care for nonfacility deliveries. None of these had rates of coverage higher than 32%, and most were below 15%.52

As mentioned previously, most maternal complications occur within 24 hours of delivery, requiring access to immediate care. Although the percentage of births with skilled attendance has increased in all regions of the world, there is still a large gap between high-income and low-income countries (Figure 4-4).1

It is important that delivery sites have the appropriate medications and technology, and well-trained staff. These sites should be affordable and accessible, and emergency transport should be provided for women who do not live near the facilities. One approach has been the development of maternal waiting homes, where women who are having problems during pregnancy, and those who are very young or very old, can stay near a hospital, receiving treatment and good nutrition.

An intermediate intervention when skilled attendance at a hospital or clinic is not possible has been to train TBAs to provide better services during delivery and to recognize complications and refer. This has been the subject of considerable controversy because some research found no difference between trained and untrained TBAs.47–49 Even skilled attendance is not necessarily enough to make a difference and is contingent on other systemic factors.53

Where skilled delivery is available in sterile clinic sites, midwives and nurses as well as doctors are able to provide more appropriate interventions, such as active management of the third stage of labor. This includes both physiologic and drug management to limit labor time and reduce maternal and infant complications such as postpartum hemorrhage and infant death. This can be done with relatively inexpensive medications (oxytocics) and simple physical maneuvers in a hospital setting and does not require extensive equipment or training.

Financial resources are not the only answer to reducing maternal mortality. Sri Lanka and Malaysia are examples of early interventions in the 1950s when they were both low-income countries with low MMRs.54 Other, more recent, examples are Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Zimbabwe.55 These examples suggest that there are many ways to improve maternal mortality in resource-poor settings. Another factor that must be considered is the inequality between income groups in accessing and receiving services.56

Almost 6 million women developed serious complications from pregnancy and childbirth in 2012, and 287,000 died.57 Hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders are the most common contributors to maternal deaths in the developing world.58 The most common causes of maternal morbidity and mortality were hemorrhage (24%), infections (15%), unsafe abortions (13%), hypertensive disorders (12%), obstructed labor (8%). These five conditions account for over 70% of the MMR. Inadequate health care, poor health status, and inadequate nutrition are the major underlying causes.2

With limited resources and deficient health care systems, many preventable emergencies occur because of lack of treatment or a delay in care.59 The “three delays model” was developed by Thaddeus and Maine to describe the complex issues preventing pregnant women from receiving adequate care.60 Phase 1 involves delay in the decision to seek care (unawareness of complications, acceptance of maternal death, and sociocultural factors such as beliefs, practices, and women’s decision-making ability), phase 2 involves delay in reaching care (due to poor roads, geographic barriers, and poor service organization), and phase 3 involves delay in receiving adequate care (because of health care system problems including lack of facilities and personnel and lack of a family’s ability to pay for services). These complex delays led to the causes of maternal death listed previously, resulting in 287,000 maternal deaths in 2012.2 Figure 4-5 illustrates the proportion of deaths attributable to these causes and interventions that have been developed to prevent or treat them.

- Hemorrhage: Severe bleeding/postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) has been identified as the most important cause of maternal death. Most (60%) of maternal deaths occur during childbirth, and half of these are within 24 hours of delivery,61 with most of these deaths due to hemorrhage. Anemia is a major contributor to maternal deaths from hemorrhage. Because the risk for hemorrhage cannot be predicted with high accuracy, skilled attendance and access to hospital services are recommended for all women. Women should be monitored for complications of hemorrhage during the immediate postpartum period. If severe bleeding occurs, women should be stabilized and referred to the next level of care.31 Uterotonics and Active Management of the Third Stage of Labor (AMTSL) provide effective interventions to prevent PPH. Uterotonics include oxytocin that is used at the facility level and misoprostol, which has been shown to be effective for home deliveries. A recent survey of 37 countries found that use of uterotonics and AMTSL had increased. Oxytocin was available in 87% of the countries and AMTSL was part of the national service guidelines for 99% of the countries (although only 48% met all the requirements). Misoprostol was less commonly accepted with only 57% of countries having it on the essential medicines list, and only a few countries actively promoting its use.62

- Infection: Postpartum endometritis, puerperal sepsis, and urinary tract infection are the most common infections following childbirth. These infections can be prevented by good prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care, especially by maintaining sterile delivery techniques. Infections must be treated immediately after occurrence to prevent chronic problems including infertility and death from generalized sepsis.63

- Unsafe abortion: In 2008, there were 43.8 million abortions, of which 49% were unsafe, resulting in 47,000 maternal deaths in developing countries.64,65 Unsafe abortion is a procedure for terminating an unwanted pregnancy by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment lacking the minimal medical standards, or both.64

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree