Learning Objectives

Overview

The multifaceted, interdisciplinary nature of global health makes for a field that has many career and educational paths leading into and stemming from it. In the last decade many health disciplines and programs have embraced global health education. This embrace has come in the forms of global health content and pathways, educational competencies, and consensus of the globalization of health science education. Despite the increasing popularity of global health education and careers, there are still many hurdles to fully actualizing this globalization. Central challenges include ensuring that global engagement occurs in an ethical fashion and garnering sustainable institutional support. Increasingly there is recognition of the necessity for interdisciplinary approaches to global health issues, which contrasts with the traditional discipline-specific silos in academic settings. There has been an emergence of organizations and schools dedicated to cutting across these silos and increasing academic institutions’ relevance in the area of global health engagement, specifically in the areas of education, research, service, and advocacy.1

There are a variety of global health program structures, content, and focus within health science and public health schools. Many Westerners who discuss global health education are referring to training students from the global north about health and health determinants in the global south. The north is the collective term for economically developed, industrialized countries, whereas the south refers to low- and middle-income countries.2 Many of these educational approaches are based on empirical evidence or impact on trainees, without attention to impact on the low-resource community hosts. There is a need for research and program development in the areas of true interdisciplinary educational engagement, program sustainability, impact on host communities, as well as cost effectiveness. Furthermore, the best use of Western professionals in global health circles is still not clear. Although some education programs encourage Westerners to be direct care providers, others see the roles as advocates and empowerment agents as more appropriate and sustainable. Lastly, there is considerable development of global health education that is occurring with south-south collaborations and within countries that show promise of developing a sustainable global health workforce.

Increased Social Accountability and the Transformation of Health Education

Two pivotal reports provide impetus for and evidence of the momentum in global health education. The Lancet commission, Education for Health Professionals for the 21st Century, produced a 2010 report to examine the state of health education worldwide and propose needed actions to address the “collective failure to share the dramatic health advances equitably.”3 The commission shared this vision:

All health professionals in all countries should be educated to mobilize knowledge and to engage in critical reasoning and ethical conduct so that they are competent to participate in patient and population-centered health systems as members of locally responsive and globally connected teams. The ultimate purpose is to assure universal coverage of the high-quality comprehensive services that are essential to advance opportunity for health equity within and between countries.

The report provides a diagnosis of current ills of the health and education systems, elaborates on their intersections, and their mutual influences. Interdependent reforms are espoused as necessary next steps. The Lancet commission included stewardship mechanisms, one of which is socially accountable accreditation of educational institutions.

A parallel effort on behalf of 65 delegates from medical education and accreditation is reflected in the Global Consensus on Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA). The GCSA defined 10 areas for schools to address to achieve social accountability. Examples of these areas include anticipating society’s health needs and adapting to the evolving role of doctors and other health professionals. Importantly, the GCSA suggests that communities where the medical school is embedded provide feedback as to the social accountability of the institution. The Consensus suggests this community assessment be used in addition to national standards for accreditation. This focus on local responsiveness and partnership is a cornerstone of the GCSA framework.4 The Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet), a consortium of community-based health education institutions that are committed to health equity, published a subsequent framework for evaluating socially accountable health professional education.5 THEnet’s efforts to increase the visibility of community-based medical schools (most of which are in the global south) that train local individuals to address local health challenges are unique. The nature of THEnet’s efforts is in contrast to many schools in the global north that train predominantly outsiders to address global health challenges in communities geographically removed from the medical school itself.

Efforts to move in the direction of more socially accountable educational institutions to affect health systems and disparities are at the heart of the global health education movement. Students have a growing interest in global health issues, health equity, and international practice.6 In response to this interest and the resultant education reform movements, a variety of global health education programs have emerged and existing programs have been strengthened. Educational programs are diverse and reflect the many facets of global health. Likewise these programs are evidence of the efforts to globalize educational systems and the health care workforce.

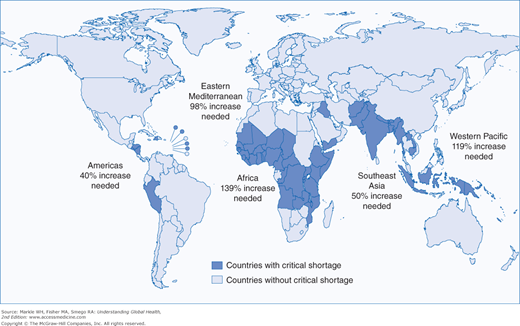

In thinking about the global workforce for health and medical care. it is important to carefully define what part of the health workforce is being described. In addition to physicians, this term also includes administrators, pharmacists, radiologists, phlebotomists, nurse midwives, physician assistants, and many other workers in health systems. We must include in the discussion the segment of the workforce that contributes to behavior change, public health, and the environment because clinical health care contributes to only about 10% of the determinants of health.7 We must not only talk about global health workers coming from Europe and North America in academic or aid projects. We should also focus on the massive shortage of many categories of skilled professionals that represents one of the greatest barriers to improved health in all countries around the globe (Figure 22-1). An all-inclusive discussion should rightly include elements of equity of salary and careful attention to true academic and intellectual exchange programs. Finally we should address not only the needs or benefits of our learners and faculty, but also the processes that promote, guide, and give local professionals in under-resourced countries the ability to gain knowledge, be retained, and have access to continuing medical education.

The Global Health Workforce Alliance (GHWA) was created in 2006 to address the crisis of chronic shortage of health care workers, approximately 4.2 million worldwide and 1.5 million in Africa alone. This new alliance represents a global partnership of national governments, civil society, international agencies, finance institutions, researchers, educators, and professional associations. Its membership now includes over 300 organizations around the world such as Johns Hopkins University, BP Korala Institute of Health Sciences in Nepal, Family Health International, Fiji School of Medicine, and the GAVI Alliance (formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation).8 At the First Global Forum on Human Resources for Health in Kampala, Uganda, in 2008, GHWA issued a declaration about an agenda for global action to address the health workforce crisis. It calls for coordinated action from governments, multilateral and bilateral, academic institutions, civil society, the private sector, and health workers’ professional associations and unions.9

Achievement of Millennium Development Goals 4, 5, 6, and 8 (child mortality, maternal health, infectious diseases, and global partnerships) hinges on a rapid increase in health care workers. For physicians, addressing these goals is an important opportunity to work with other professional groups to understand how to distribute energy and dollars toward programs that support other health workers who are needed in a functional local and national health care system.

The current definition of global health properly includes the underserved and impoverished areas of all nations, developed and developing. Many have struggled with how to provide a description that allows for a common ground for discussions, proposals, and actions. Koplan and others offered that:

Global health is an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions, involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. It is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.10

There is a recognized contradiction when health care personnel from high-resource countries get on planes that fly over their own urban slums and poor rural communities in an effort to address impoverished communities across the globe. The issue of persistent local health disparities, particularly in the United States, must be considered. It is fairly recognized that successful health systems require a primary health care workforce and infrastructure to be sustainable, cost effective, and culturally competent. Among physicians from developed countries there is an emerging tension about the focus of work that is needed to support improved health care. Traditionally, medical missions often consisted of surgeons, obstetrician/gynecologists, and infectious disease specialists that focused on specific diseases that could be addressed by one-time medications, treatments, and procedures. This specialist view is often supported by academic institutions in the less developed countries, which have been modeled on specialist-oriented sister institutions in North America and Europe. The emergence of primary care and primary health care as central foci of health care services and human resources in health in both the developed and developing world has created an increased demand for family physicians, primary care internists, pediatricians, obstetricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurse midwives, both as providers and educators. Dr. Margaret Chan, in an address to the International Conference on Health for Development in Buenos Aires in 2007, noted that the path to reduced maternal and child deaths and more coverage for malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and chronic diseases will be a rapid buildup of primary health care staff more than technology.11

Supporting rapid scaling up of primary health care capabilities in the developing world will be difficult to achieve without a retooling of medical education and postgraduate training that produces more primary care providers and health care workers inherent in the new primary care model. For the struggling countries of Asia, Africa, and Central/South America, this enormous task seems impossible unless efforts to help are adapted to increasing the relevant human resources for health. The impact of brain drain and conflict on shortages of physicians continues to worsen. As of early 2008, countries such as Kenya, Ghana, Angola, and Mozambique had 43% to 75% of their trained physicians working abroad.12 South Sudan, the newest country on the planet, offers a stark example of a country that lacks both the basic workforce to staff a central hospital or a training institution to train needed medical students and residents. Conflicts and lack of basic infrastructure outside the capital prevents the establishment of even the most rudimentary primary care outposts.

The huge workforce focus on vertical programs, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, exposed more than ever the inequities and inadequacies of human resources in developing countries. This realization has driven the most recent, and somewhat controversial, effort to scale up the physician workforce to address the inequities in the developing world. The Institute of Medicine (IOM), as requested by the Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator, began to study options for placing US health care professionals in 15 focus countries. The IOM proposed a Peace Corps–style recruitment and mobilization effort. The report stated, “Nothing less than a Peace-Corps scale contingent of health care professionals and other experts should be mobilized to plan, carry out, and sustain a campaign against the disease.”13

The proposed Global Health Service, circa 2005, envisioned six programs:

- 1. Global Health Service Corps

- 2. Health Workforce Needs Assessment

- 3. Fellowship Program

- 4. Loan Repayment Program

- 5. Twinning Program

- 6. Clearinghouse

The Global Health Service Corps is now a reality with the July 2012 launch of the Global Health Service Partnership. The workforce goal is to offset shortages in human resources and to promote direct work with local communities. This program is a public-private partnership between the PEPFAR, Peace Corps, and the Global Health Service Corps. The nurses and physicians will primarily serve as adjunct faculty in existing training programs. The first three countries will be Tanzania, Malawi, and Uganda starting in July 2013. These positions will use licensed physicians and nurses, but, like Peace Corps volunteers, they will only get monthly stipends, transportation, medical care, vacation time, and a readjustment allowance. The initial commitment will be 1 year with an opportunity to extend for a second year.14

The “twinning” program, mentioned in the original proposal, started in 2010. The Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) is intended to strengthen health systems, educational programs, and boost the numbers of health workers to 140,000 over a much longer term.15 This effort, also using repurposed PEPFAR funds, is an attempt to develop “twinned” relationships between US academic institutions and severely under-resourced institutions in a number of sub-Saharan African countries. Similar to the Global Health Service Corps, much of the initial attention is on Africa because it has 24% of the global burden of disease, but only 3% of the global health workforce and only 1% of the world’s health expenditure.16 MEPI has a $130 million budget and uses the resources of Health and Human Services, PEPFAR, the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and more than 15 major American universities working with multiple educational institutions in over 10 sub-Saharan African countries. This project, in part, was an effort to address the redirecting of funds from AIDS programs. Many experts felt these programs overlooked the needs of many countries to have more trained health care workers and to pay more attention to the basic health issues of water, sanitation, nutrition, and chronic diseases.17

These recent efforts to focus more on the training and support of health systems development should stimulate debate and discussion about ethical issues to avoid harm and to be thoughtful about future outcomes of current actions or assistance. This is especially important for students, trainees, and residents who are contemplating going abroad either as individuals or part of a larger academic or nongovernmental organization. Although the phrase primum non nocere “first do no harm,” generally applies to the care and treatment of individual patients, it should also apply to communities and governmental agencies in the countries being supported. Much like the traditional “vertical” programs that diverted health care workforce and resources from preexisting nutritional, public health, and chronic disease programs in many countries, a new dependence on a Peace Corps model of short-term medical volunteers may retard longer term more sustainable solutions in developing countries.

A public debate on the New York Times editorial page in 2008 underscored this dilemma. Two former volunteers, one a US senator and the other a former recruiter and country director, offered their opinions about either doubling the number of volunteers (the senator) or being more circumspect in sending short-term volunteers that are not requested and may not be needed.18 Older programs, such as the Foundation for the Advancement of International Medical Education and Research, were focused on improving capacity and capability of faculty in medical/nursing training institutions abroad to innovate and develop appropriate models for trainees. This type of indirect aid, not medications or workforce, has the potential to keep foreign physicians in place and, simultaneously, develop professional and equitable relationships with medical educators around the world.19

One model of low-budget cooperative efforts, called the Friends of Family Medicine Uganda (FFMU), under the aegis of an international advisory committee, stresses the collaborative development of family medicine curricula, residency programs, and family medicine faculties in that country. Rather than spend weeks or months struggling to treat diseases and place bandages on broken delivery systems, participating FFMU faculty from Europe, Canada, and the United States work with their African counterparts electronically and in periodic visits/conferences.

Another larger project, funded by the European ACP-Eu-Edulink, works from a similar framework in a collection of sub-Saharan countries. Known as Primafamed, faculties from Europe and the United States supported meetings and the development of an online primary health care and family medicine journal established in 2009.20 The Primafamed network currently provides a platform for those African educational institutions concerned with issues of primary health care and family medicine. It helps to provide training to increase the necessary capacity in countries such as South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, Nigeria, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Tanzania, and Kenya.21

Moreover, the VLIR ZEIN 2009 program, funded by the Belgian government and the Flemish Interuniversity Council, has established a “South African family medicine twinning project.” The departments of family medicine in South Africa twin with those training complexes that have been or will be set up in Namibia, Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, Lesotho, Swaziland, the DRC, and Botswana. Primafamed gives support in terms of capacity building, content development, and the monitoring of postgraduate training in family medicine. This network is fostering the principle of south-south cooperation, by encouraging the sharing of unique knowledge and wisdom among different African institutions, as well as by creating an institutional network.22

Of particular concern to global health is the increasing emigration of health care workers in response to market forces.23 With the movement of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists out of economically disadvantaged environments to developed countries, there looms a crisis of care in developing countries. For example, Africa bears 25% of the world’s disease burden but has only 0.6% of the world’s health care professionals. More than a third of South African medical school graduates immigrate to the developed world each year. In Zimbabwe, where pharmacists provide substantial primary care, only 40 are trained each year, and in 2001, 60 migrated abroad. Ethical solutions to these labor flows are needed; these may include educational and institutional incentives that link academic institutions in developed countries to partner institutions in developing countries. In 2011, approximately 2,700 non-US international medical graduates matched for residency training in the United States.24 This represents over 10% of all first-year residents and represents a significant loss of physician workforce for countries that can least afford it. It also shows how the United States (and likely Europe) is simultaneously taking talent from less resourced countries while preparing a legion of their own physicians to go there through the new global health service corps.

Certainly, models for the contribution of health manpower from better resourced environments to high-need areas exist. Cuba has been contributing physicians to developing countries for decades as a community service requirement for its new graduates; in fact, it has extended its concern for underserved areas by training US medical students to treat poor urban Americans. Thousands of medical students from other less developed countries are trained in Cuba to return home to serve local needs.25

As discussed in the section about research activities, health research partnerships have considerable benefits that enhance the quality of research, the exchange of knowledge between counterparts, and the development of focused research capacity in global health. A recent product of just such a focus, conducted by the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research and supported by the International Development Research Centre, was the development of a “Partnership Assessment Toolkit.”26 A central goal of the toolkit is to break down the tension that exists in many research and assistance initiatives from developed countries and the lack of true empowerment and ownership created by top-down neocolonial models.

Recently an important report by the Global Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century in Lancet attempted to point the way toward closing gaps in health equity and workforce within and between countries.3 The primary focus of the report was transforming education to strengthen health systems. This systems centered approach has clear implications for the health care workforce and for North American and European students, postgraduates, and residents. A commentary by several European students from Austria and the Netherlands endorses this new approach:

We encourage the proposed team-based education to breakdown professional silos. Working in health care means working within multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teams. As teamwork is a soft skill which can be learned, its development should be fostered by the proposed inter-professional courses starting at an early age. In the past seven years, international health-care students recognized the importance of inter-professional education, and launched an international forum which brings together students of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health professions.27

Frameworks for Global Health Education

Global health education occurs at all levels of medical education: premedical undergraduate, undergraduate medical education (medical school), graduate medical education (residency), and postgraduate medical education (i.e., residencies and fellowships). It also occurs in allied health, public health, nursing, and other health education schools. In addition, global health and similar themes are studied in most nonhealth disciplines, with particular attention in geography, women’s studies, anthropology, and other social sciences. Because determinants of health are so broad, especially in the developing world, global health education is the subject of business, engineering, political science, and many other disciplines. Even when not conceived as explicitly global health education, the concepts, principles, and interventions of most disciplines when applied in a globalized fashion are integrated into global health in its most inclusive form.

Within health-specific and health-related disciplines, explicit global health education takes many forms:

- Undergraduate programs (nonprofessional schools) in international relations, public health, anthropology, etc.

- Certificate programs, applying to both visiting scholars and professional school students who concentrate on global health.

- Global health tracks for students in medicine, pharmacy, nursing, dentistry, and veterinary medicine.

- A global health elective or required coursework during undergraduate medical, nursing, or allied health education.

- Master’s degrees in global health sciences or clinical research focusing on global health topics.

- Areas of concentration for doctoral students in basic sciences, nursing, or other fields to support research projects in global health.

- Clinical scholar programs for residents who wish to expand their clinical training to include research, service, or program work abroad.

- Participation in student-run local, national, and international organizations (i.e., IFMSA, GlobeMed, Unite for Sight, Global Brigades) as well as participation in professional groups (i.e., AAFP’s Global Health Workshop, ACS Operation Giving Back, AAP Section on International Child Health), consortiums (i.e., CUGH, WONCA), and other national/international organizations (i.e., Doctors for Global Health, Physicians for Social Responsibility).

- Participation in international rotations or study abroad programs through academic institutions or nongovernmental organizations (i.e., Child Family Health International, Cross Cultural Solutions, others).

There is no agreed upon or universal structure to global health education.28 Bozorgmehr and colleagues presented key characteristics of global health education that emphasizes important concepts such as inter- professionalism, focus on social justice, and critical thinking (Table 22-1).29 However each program is a reflection of its own institutional strengths, faculty capabilities, global health agenda, unique philosophy, and underlying ethical approach.30

Category | Characteristics | Implication | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

Object | Focuses on social, economic, political and cultural forces which influence health across the world | Learning opportunities in “global health” focus on the underlying structural determinants of health | To ensure that educational interventions cover the social, economic, political and cultural etiology of ill health, and not merely its disease-oriented symptoms on a global level |

Concerned with the needs of developing countries; with health issues that transcend national boundaries; and with the impact of globalization | Learning opportunities in “global health” link territorial up to supraterritorial dimensions of underlying structural determinants of health | To ensure that educational interventions clarify the links between territorial health situations (either domestic ones and/or situations in other countries) and their underlying transborder and global determinants | |

Orientation | Toward “health for all” | Learning opportunities in “global health” should adopt and impart the ethical and practical aspects of achieving ‘health for all’ | To ensure that educational interventions are relevant to people’s needs on community, local, national, international and global level |

Toward health equity | Learning opportunities in “global health” should emphasize issues of health equity (or health inequity) within and across countries | To ensure that educational interventions orientate on the challenge of achieving health equity worldwide | |

Outcome | Identification of actions | Learning opportunities in “global health” facilitate the identification of actions (by the student), undertaken to resolve problems either top-down or – more important- bottom-up | To ensure that educational interventions foster critical thinking and present options for professional engagement on different dimensions towards “health for all” and health equity |

Methodology | Cross-disciplinarity | Learning opportunities in “global health” involve educators and/or students from various disciplines and professions | To ensure that educational interventions lead to an understanding of influences on health beyond the biomedical paradigm and respect the importance of sectors other than the health sector in improving health |

Bottom-up learning and problem-orientation | Learning-opportunities in “global health” require unconventional methods for teaching and learning | To ensure that educational interventions clarify the relevance for the health workforce to deal with transborder and/or global determinants of health |

Many from the global north refer to global health education programs as those at global north institutions that teach global health concepts to a predominantly Western trainee population. However there are also those that focus on training individuals from the global south to serve their own communities. This occurs through grassroots capacity building activities, formal educational institutions, and twinning programs. Grassroots capacity building usually occurs at the community or provincial level. These activities include training of community health workers, existing health care professionals, and others. Although this process occurs internally, the literature predominantly reflects education programs and capacity building that involves facilitators from the global north.31–33

Formal educational institutions that train local student populations exist throughout the world. There has been a growth and collaboration of such institutions dedicated to educating local individuals to be physicians, midlevel providers, nurses, and pharmacists who are dedicated to caring for the underserved in their own countries and regions. THEnet is a consortium of 11 medical schools around the world committed to training health care providers who are embedded in the community, responsive to its needs, and dedicated to a social justice agenda. This is in contrast to the traditional ivory tower view of medical schools. Traditional ivory tower academic institutions are perceived as out of touch with the communities where they are located, concerned with technological advancement at the expense of equitable dissemination of existing resources, and generally not exemplifying priorities consistent with health equity.34–37

Although there is still a dearth of training institutions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, the support of institutions training local populations to address their own health needs and engage in global health from the southern perspective is crucial for sustainable impacts. There is an increasing role for south-south partnerships for education and health services, in addition to north-south partnerships aiming to improve education and retention.38–40

In addition to multiple frameworks that exist for global health education programs and partnership structures, there are also many lenses through which to view the competencies and goals of such an education.

The utilization of competencies as predefined outcomes of medical, health science, and other fields of education has surged in recent years. Known as Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) in the medical field, this approach is defined as “an outcomes-based approach to the design, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of medical education programs, using an organized framework of competencies.” Frank et al identified four overarching themes that guide CBME: focus on outcomes, emphasis on abilities rather than solely knowledge, de-emphasis on time-based training, and promoting greater learner centeredness.41

The global health education community has called for increased reliance on competencies and standardization of curriculum.42,43 A nominal group process at the Bellagio Conference, convened at the Rockefeller Center in 2008, found that cultural humility was the most important global health education competency. Several sets of competencies have been developed for global health education. However, there still is no consensus or standardization of competencies, and many programs are developed without even the guidance of learning objectives.44

Competencies in global health can be categorized into essential core competencies and specialized competencies. Core competencies are those necessary for all medical students regardless of interest in global health. Specialized competencies are relevant for trainees seeking expanded global health training, usually through tracks, distinction, certificates, fellowships, or the like. Four domains of competencies have been suggested as core for all medical students: global burden of disease, traveler’s medicine, immigrant health, and cultural awareness.45,46 These domains were expanded by the Joint US/Canadian Committee on Global Health Essential Core Competencies (Table 22-2). In addition to identifying knowledge domains and competencies, the committee went a step further to discuss how students can demonstrate each competency.

Knowledge Domains |

|---|