4 The head and neck

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

1. Find, recognize and name the constituent components of the external surface of the skull, noting their size and position.

2. Palpate many of the bony features, being able to relate one to another.

3. Locate, name and palpate the bony and cartilaginous structures at the front of the neck.

4. Recognize and palpate bony landmarks of the cervical spine.

5. Name all the joints of the skull, recognizing the bones which form them.

6. Palpate and trace the lines of the sutures and joints of the skull and cervical spine, where possible, indicating their bony landmarks and surface markings.

7. Describe or carry out any accessory movements possible, noting the ranges in which they are most evident.

8. Note the range of movement of the cervical spine and indicate the factors limiting the movement.

9. Give the class and type of each of the joints.

10. Name and demonstrate the action of all the muscles palpable in the head and neck.

11. Draw the shape of the muscle on the surface and palpate its contraction.

12. Name all the main cutaneous nerves supplying the head and neck, giving their distribution.

13. Name the main arteries of the head and neck, giving their course and distribution.

14. Name the main veins of the head and neck, noting their drainage areas and course.

Bones

The skull

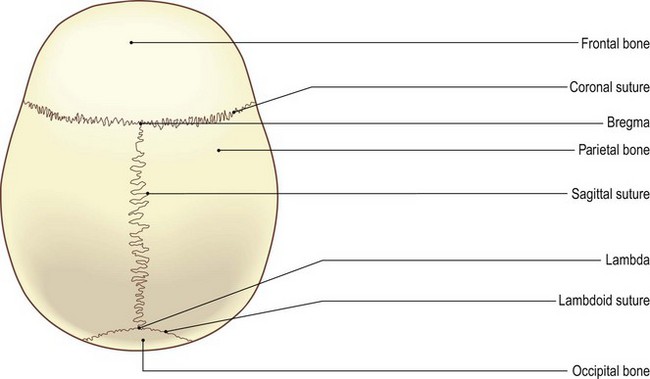

Superior aspect (Fig. 4.1a)

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the sitting position.

• The sagital suture. Place your fingers anterior and posterior to the vertex of the skull. On pressing the tips in and moving them from side to side, the sagittal suture can be palpated, particularly posteriorly.

• The point of lambda. Halfway between the vertex and the external occipital protuberance a hollow can be felt with two sutures running downwards and laterally in front of the occipital bone. This is the point ‘lambda’.

• The point of bregma. Moving approximately 5 cm forwards from the vertex there is another palpable slight hollow with the coronal suture running laterally to either side. This point is termed ‘bregma’.

• The frontal bone (forehead). In front of the coronal suture the frontal bone can be palpated, sometimes with a central raised line where the two bones have fused.

• The parietal bones. Either side of the sagittal suture, behind the frontal bones and in front of the occipital bone, are the two large plates of the parietal bones.

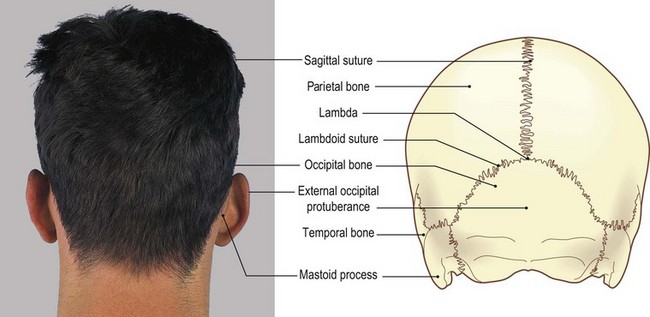

Posterior aspect (Fig. 4.1b, c)

Palpation

• The external occipital protuberance. The most prominent bony feature of the posterior aspect of the skull is the external occipital protuberance situated just below its centre. It varies in size and shape between individuals, being large and prominent in some and difficult to find in others.

• The superior nuchal lines of the occipital bone. Radiating laterally and upwards from the external occipital protuberance are the two superior nuchal lines. (Nuchal: believed to come from Arabic ‘nugraph’ = the back of the neck.) These are palpable in their central section on most subjects, but are difficult to trace for more than a few centimetres laterally.

• The sagital suture. Approximately 5 cm above the external occipital protuberance the sagittal suture meets two occipitoparietal sutures. In the young child this is the region of the posterior fontanelle [fons (L) = small fountain or spring], which in the adult becomes the lambda.

• The occipital bone. Inferiorly the occipital bone can be traced forwards under the skull, but is soon lost in the deep hollow at the level of the tubercle of the first cervical vertebra.

• The mastoid process of the temporal bone. Moving to either side, just behind the pinna of each ear, the mastoid process of the temporal bone can be palpated. It is pointed at its inferior aspect where the sternocleidomastoid muscle attaches.

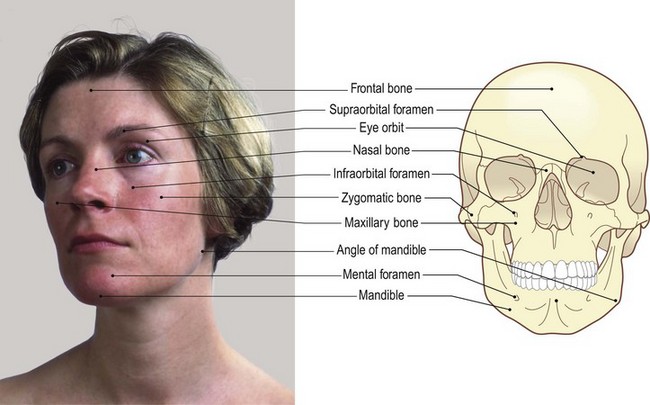

Anterior aspect (Fig. 4.2a, b)

Palpation

• The eye orbit. Deep to the eyebrow the upper rim of the eye orbit can be palpated, being slightly notched at its centre where it is crossed by the supraorbital artery. The whole margin of the orbit is subcutaneous and can thus readily be palpated.

• The two nasal bones. These can be palpated centrally, projecting forwards and continuing as a cartilage down to the centre of the nose.

• The upper part of the maxilla. Below this, the upper part of the maxilla can be palpated, investing the upper teeth.

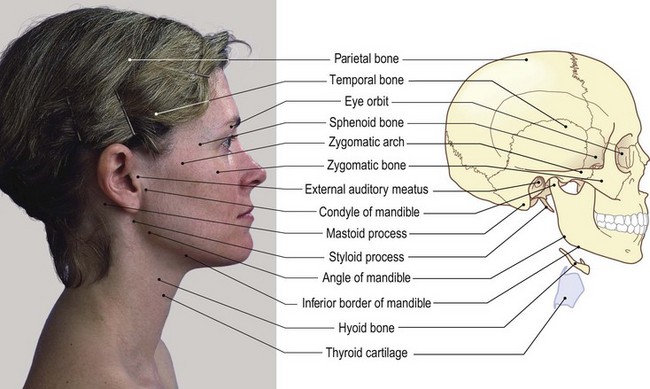

Lateral aspect (Fig. 4.2c, d)

Palpation

• The external auditory meatus. This is an obvious landmark on the lateral side of the head. The little finger can be pressed deep into this opening to be surrounded by its bony walls. The pinna lies around three sides, while the tragus is the pointed area of soft tissue overlapping the meatus from the front.

• The zygomatic arch. Running horizontally forwards just anterior to the tragus [tragos (Gk) and tregus (L) = a goat (possibly pertaining to the shape of a goat’s beard)], a bony bridge can be palpated. This is the zygomatic arch. It forms the point of the cheek at the front where it joins the zygomatic bone (Fig. 4.2c, d). The arch is formed partly from the temporal and partly from the zygomatic bones.

• The condyle of the mandible. Below the posterior part of the zygomatic arch anterior to the tragus a small tubercle can be palpated. This is the most lateral part of the condyle of the mandible. If the model opens the mouth, this bony prominence can be felt, first rotating then moving forwards and downwards over the articular eminence of the temporal bone.

• The angle of the mandible. Some 7 cm directly below the condyle of the mandible, the angle of the mandible can be identified, being more prominent in men than in women as it is slightly everted.

• The inferior border of the mandible. This can be traced forward to a raised vertical line centrally at the front, where it joins the bone of the opposite side.

• The mental tubercle. A small tubercle (the mental tubercle) can be palpated on the inferior border either side of this line.

• The anterior and lateral surfaces of the mandible. These are subcutaneous and can be traced posteriorly as far as the angle where they are hidden by the powerful muscles of mastication. The lower border is thickened all round, giving a concave appearance to the anterior surface.

• The maxilla. Below the zygomatic bone the maxilla can be palpated, with the teeth and gums easily identifiable through the flesh of the cheek and the upper lip.

The neck

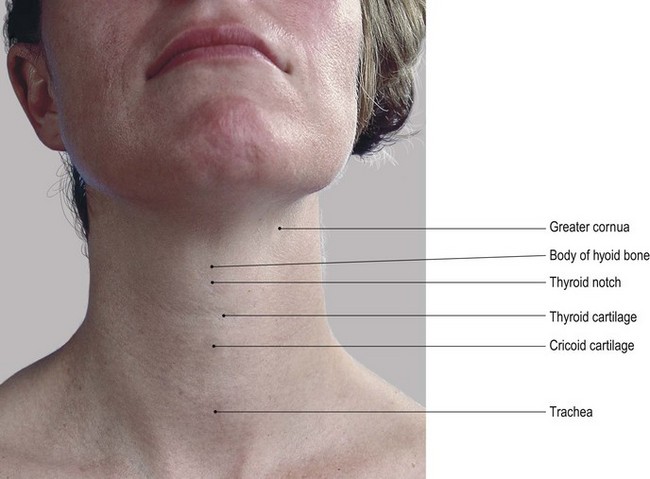

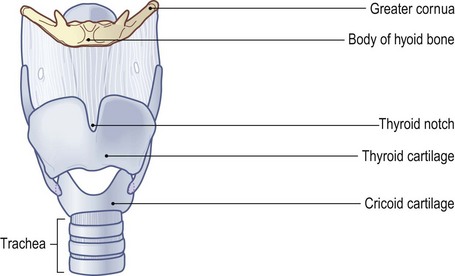

Anterior aspect (Fig. 4.3a, b)

Palpation

• The hyoid bone. Place the fingers and thumb of one hand on either side of the mandible halfway along its inferior border. Then slide your fingers and thumb down on to the sides of the throat. Some 3–5 cm below the mandible, you will feel the hyoid bone lying almost horizontal. It will appear as a horseshoe-shaped structure, rounded and thicker anteriorly and becoming pointed on either side posteriorly as it curves upwards slightly. This is the greater wing (cornua). Gentle pressure applied to either side will confirm its bony consistency.

• The laminae of the thyroid cartilage. Continue down the sides of the neck from the hyoid. After crossing a small space (felt as a depression), you will encounter the broad flat lamina of the thyroid cartilage on either side. Each lamina is angled medially so that they meet in the midline anteriorly.

• The larynx. A marked projection (the laryngeal prominence), more pronounced in men, can be felt superiorly in the midline. This projection is commonly referred to as the ‘Adam’s apple’.

• The thyroid notch. Now place your finger on the anterosuperior aspect of this prominence. You will identify a small space, concave upwards: this is the thyroid notch.

• The cricoid cartilage. Trace down the sides of the thyroid cartilage for about 4 cm to a line just above the level of the medial ends of the clavicles. Here, after crossing another small space, you will palpate a further ring-shaped structure. This is the cricoid cartilage which presents with a small tubercle at its centre.

• The trachea. Below the cricoid cartilage and deep in the supra-sternal (jugular) notch you can palpate the cartilaginous rings of the upper part of the trachea.

• Note. Each of the structures identified above can be taken between the finger and thumb of the same hand and carefully moved from side to side for a distance of about 1 cm. Too much side movement can, however, lead to tenderness in this part of the neck. During swallowing, each of the structures rises and then falls approximately 1 cm.

• The sternocleidomastoid muscle. This muscle can be felt on either side of these central structures. This is facilitated if the model adopts the supine lying position. Ask the model to raise the head from a pillow. These muscles are widely spaced at the level of the hyoid bone but become much closer together as they approach the level of the clavicles.

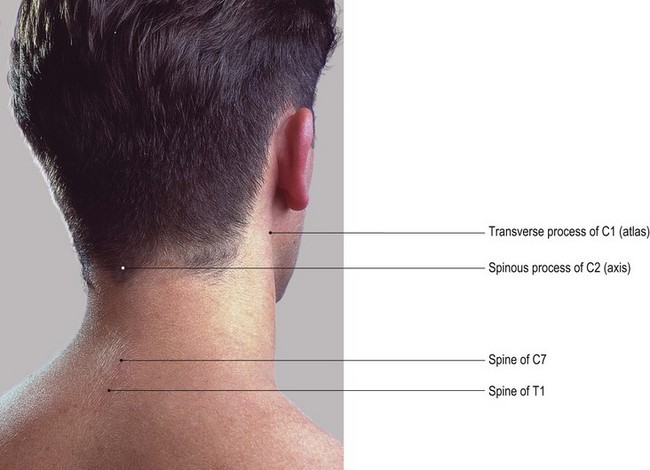

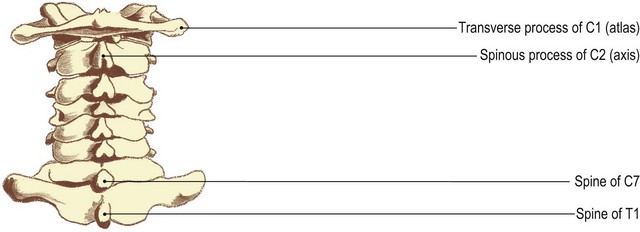

Posterior aspect (Fig. 4.4)

Palpation

• The external occipital protruberance. Begin the palpation by finding the external occipital protuberance, with the raised crescentic superior nuchal lines curving laterally.

• The external occipital crest. Running inferiorly and under the back of the skull from the protuberance, you can palpate the external occipital crest It ends at a deep hollow which is level with the tubercle of the atlas (not palpable). The hollow is bounded below by the large prominence of the spine of the axis. This is approximately 3 cm below the external occipital protuberance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree