Table 8.1)

Patients with anaemia may present with weakness, tiredness, dyspnoea, fatigue or postural dizziness. Anaemia due to iron deficiency is often the result of gastrointestinal blood loss, or sometimes recurrent heavy menstrual blood loss, and so these symptoms should be sought. Disorders of platelet function or blood clotting may present with easy-bruising or bleeding problems. Recurrent infection may be the first symptom of a disorder of the immune system, including leukaemia or HIV infection. The patient may have noticed lymph node enlargement, which can occur with lymphoma or leukaemia. Not all lumps are lymph nodes; consider the differential diagnosis (

TABLE 8.1 Haematological history

| Major symptoms |

| Symptoms of anaemia: weakness, tiredness, dyspnoea, fatigue, postural dizziness |

| Bleeding (menstrual, gastrointestinal, after dental extractions) |

| Easy bruising, purpura, thrombotic tendency |

| Lymph gland enlargement |

| Bone pain |

| Infection, fever or jaundice |

| Enlargement of the tongue from amyloidosis |

| Paraesthesiae (e.g. B12 deficiency) |

| Skin rash |

| Weight loss |

TABLE 8.2 Differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy

| 1 Lipoma—usually large and soft; may not be in lymph node area |

| 2 Abscess—tender and erythematous, may be fluctuant |

| 3 Sebaceous cyst—intradermal location |

| 4 Thyroid nodule—forms part of thyroid gland |

| 5 Secondary to recent immunisation |

Treatment

Anaemia may have been treated with iron supplements or B12 injections. Anti-inflammatory drugs or anticoagulants may be the cause of bleeding. Treatment for leukaemia or lymphoma may have involved chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both; or bone marrow transplant. There may have been blood transfusions in the past.

Past history

A history of gastric surgery or malabsorption may give a clue regarding the underlying cause of an anaemia. Anaemia in patients with systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or uraemia can be multifactorial. Previous blood transfusions may have been required to treat the anaemia. On the other hand, patients with polycythaemia may have had many venesections (

Social history

A patient’s racial origin is relevant. Thalassaemia is common in people of Mediterranean or southern Asian origin. Rarely, very strict vegetarian diets can result in vitamin B12 deficiency. Find out the patient’s occupation and whether there has been work exposure to toxins such as benzene (risk of leukaemia). Has the patient had previous chemotherapy for a malignancy (drug-related development of leukaemia)? Does the patient drink alcohol?

Family history

There may be a history of thalassaemia or sickle cell anaemia in the family. Haemophilia is a sex-linked recessive disease while von Willebrand’s disease

TABLE 8.3 Causes of ecchymoses

| Trauma |

| Thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction ( |

| Senile ecchymoses (due to loss of skin elasticity) |

The haematological examination

Haematological assessment does not depend only on the microscopic examination of the blood constituents. Physical signs, followed by examination of the blood film, can give vital clues about underlying disease. Haematological disease can affect the red blood cells, the white cells, the platelets and other haemostatic mechanisms as well as the mononuclear-phagocyte (reticuloendothelial) system.

Examination anatomy

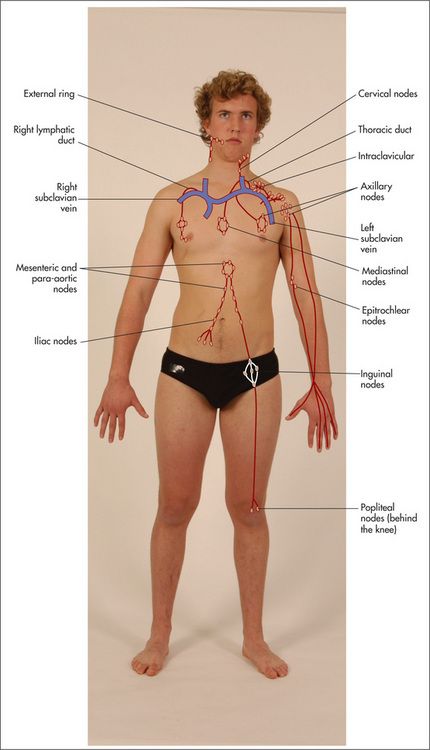

An important part of the examination involves assessment of all the palpable groups of lymph nodes. As each group is examined its usual drainage area must be kept in mind (

General appearance

Position the patient as for the gastrointestinal examination—lying on the bed with one pillow. Look for signs of wasting and for pallor (which may be an indication of anaemia—

The hands

The detailed examination begins in the usual way with assessment of the hands. Look at the nails for koilonychia—these are dry, brittle, ridged, spoon-shaped nails, which are rarely seen today. They can be due to severe iron deficiency anaemia, although the mechanism is unknown. Occasionally koilonychia may be due to fungal infection. They may also be seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Digital infarction (

Note any changes of rheumatoid or gouty arthritis, or connective tissue disease (

Now take the pulse. A tachycardia may be present. Anaemic patients have an increased cardiac output and compensating tachycardia because of the reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of their blood.

Look for purpura (

Scurvy (vitamin C deficiency)—classically perifollicular purpura on the lower limbs, which is almost diagnostic of this condition |

* Eduard Henoch (1820–1910), professor of paediatrics, Berlin, described this in 1865, and Johannes Schönlein (1793–1864), Berlin physician, described it in 1868.

If the petechiae are raised (palpable purpura), this suggests an underlying systemic vasculitis, where the lesions are painful, or bacteraemia.

The forearms

If thrombocytopenia or capillary fragility is suspected, the Hess test

Epitrochlear nodes

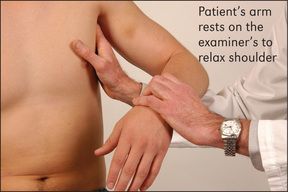

These must always be palpated. The best method is to flex the patient’s elbow to 90 degrees, abduct the upper arm a little and then place the palm of the right hand under the patient’s right elbow (

TABLE 8.5 Characteristics of lymph nodes

TABLE 8.6 Causes of localised lymphadenopathy

| 1 Inguinal nodes; infection of lower limb, sexually transmitted disease, abdominal or pelvic malignancy; immunisations |

| 2 Axillary nodes; infections of the upper limb, carcinoma of the breast, disseminated malignancy; immunisations |

| 3 Epitrochlear nodes; infection of the arm, lymphoma, sarcoidosis |

| 4 Left supraclavicular nodes; metastatic malignancy from the chest, abdomen (especially stomach—Troiser’s sign) or pelvis |

| 5 Right supraclavicular nodes; malignancy from the chest or oesophagus |

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 8.1 Factors suggesting lymphadenopathy is associated with significant disease

| LR if present | LR if absent | |

| Age > 40 | 2.4 | 0.4 |

| Weight loss | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| Fever | NS | NS |

| Head and neck but not supraclavicular | NS | NS |

| Supraclavicular | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| Axillary | 0.8 | NS |

| Inguinal | 0.6 | NS |

| Size: | ||

| < 4 cm2 | 0.4 | — |

| 4–9 cm2 | NS | — |

| > 9 cm2 | 8.4 | — |

| Hard texture | 3.3 | NS |

| Tender | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Fixed node | 10.9 | NS |

| 3 or fewer nodes | 0.04 | — |

| 5 or 6 nodes | 5.1 | — |

| 7 or more nodes | 21.9 | — |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Axillary nodes

To palpate these, the examiner raises the patient’s arm and, using the left hand for the right side, pushes his or her fingers as high as possible into the axilla. The patient’s arm is then brought down to rest on the examiner’s forearm. The opposite is done for the other side (

There are five main groups of axillary nodes: (i) central; (ii) lateral (above and lateral); (iii) pectoral (medial); (iv) infraclavicular; and (v) subscapular (most inferior) (

The face

The eyes should be examined for the presence of scleral jaundice, haemorrhage or injection (due to increased prominence of scleral blood vessels, as in polycythaemia). Conjunctival pallor suggests anaemia and is more reliable than examination of the nail beds or palmar creases.

The mouth should be examined for hypertrophy of the gums, which may occur with infiltration by leukaemic cells, especially in acute monocytic leukaemia, or with swelling in scurvy. Gum bleeding must also be looked for, and ulceration, infection and haemorrhage of the buccal and pharyngeal mucosa noted. Atrophic glossitis occurs with megaloblastic anaemia or iron deficiency anaemia. Multiple telangiectasiae may appear around the mouth or in the mouth in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Look to see if the tonsils are enlarged. Waldeyer’s ring

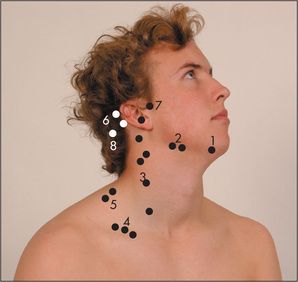

Cervical and supraclavicular nodes

Sit the patient up and examine the cervical nodes from behind. There are eight groups. Attempt to identify each of the groups of nodes with your fingers (

Figure 8.7 Cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes

1 = submental; 2 = submandibular; 3 = jugular chain; 4 = supraclavicular; 5 = posterior triangle; 6 = postauricular; 7 = preauricular; 8 = occipital.

TABLE 8.7 Causes of lymphadenopathy

| Generalised lymphadenopathy Infections: viral (e.g. infectious mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus, HIV), bacterial (e.g. tuberculosis, brucellosis, syphilis), protozoal (e.g. toxoplasmosis) Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|