Table 7.1)

These may include a change in the appearance of the urine, abnormalities of micturition, suprapubic or flank pain or the systemic symptoms of renal failure. Some patients have no symptoms but are found to be hypertensive or to have abnormalities on routine urinalysis or serum biochemistry. Others may feel unwell but not have localising symptoms (

Table 7.1 Genitourinary history

| Major symptoms |

Questions box 7.1

Questions to ask the patient with renal failure or suspected renal disease

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Table 7.2 The major renal syndromes

| Name | Definition | Example |

| Nephrotic | Massive proteinuria | Minimal change disease |

| Nephritic | Haematuria, renal failure | Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis |

| Tubulointerstitial nephropathy | Renal failure, mild proteinuria | Analgesic nephropathy |

| Acute renal failure | Sudden fall in function, rise in creatinine | Acute tubular necrosis |

| Rapidly progressive renal failure | Fall in renal function, over weeks | Malignant hypertension or ‘crescentic’ glomerulonephritis |

| Asymptomatic urinary abnormality | Isolated haematuria, or mild proteinuria | Immunoglobulin A nephropathy |

* Newly defined as acute kidney injury, AKI; Levin A, Warnock D, Mehta R, Kellum J, Shah S, Melitoris B, Ronco C. Improving outcome for AKI. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50(1):1–4.

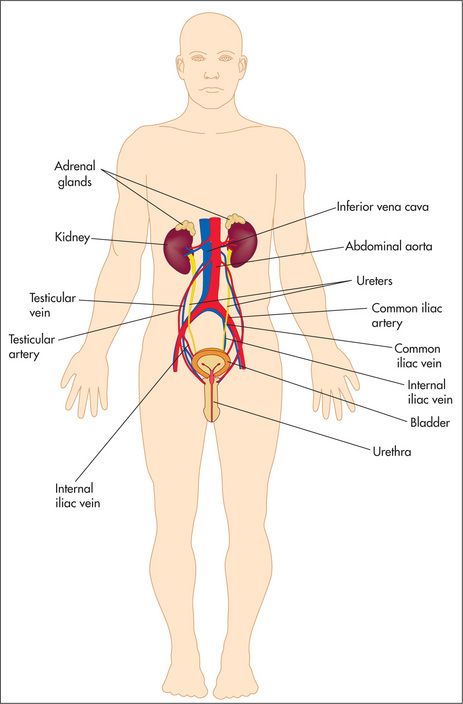

Examination anatomy

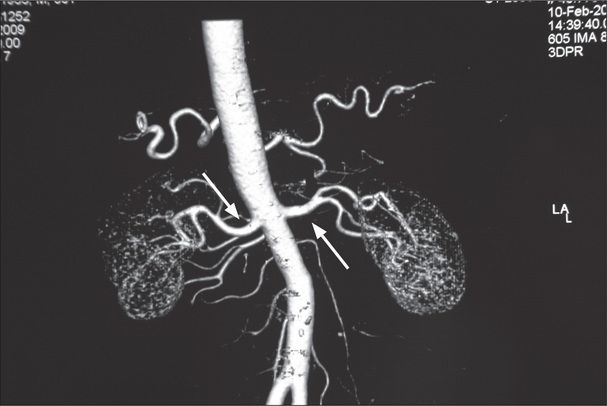

Figure 7.2 CT angiogram showing the origins and course of the renal arteries (large arrows) from the abdominal aorta; the left and right inferior phrenic arteries are visible arising superiorly

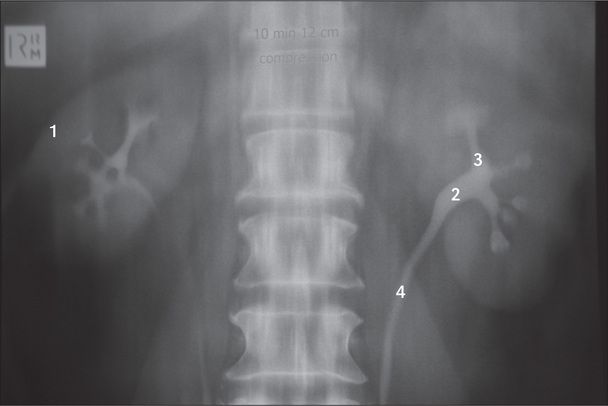

Figure 7.3 Outline of the renal collecting system

This intravenous pyelogram shows the outline of the kidneys (1), the renal pelves (2) and the calyces (3) and ureters (4).

Basic male and female reproductive anatomy is shown in

Change in appearance of the urine

Some patients present with discoloured urine. A red discoloration suggests haematuria (blood in the urine).

| 1 Favours urinary tract infection |

| 2 Favours renal calculi |

| 3 Favours source not glomerular |

| 4 Favours blood not in urine |

| 5 Favours immunoglobulin A nephropathy |

| 6 Favours trauma |

| 7 Favours bleeding disorder |

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

This condition includes both upper urinary tract (renal) infection and lower UTI (mostly the bladder—cystitis). Possibly as many as 50% of lower UTIs also involve the kidneys. Renal infection may be difficult to distinguish clinically from lower UTIs but is a more serious condition and more likely to involve systemic complications such as septicaemia.

Urinary tract infection is much more common in women than in men, but there are a number of risk factors for the disease (

Table 7.4 Risk factors for urinary tract infection (UTI)

| Female sex |

| Coitus |

| Pregnancy |

| Diabetes |

| Indwelling urinary catheter |

| Previous UTI |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms of obstruction |

Urinary obstruction

Urinary obstruction is a common symptom in elderly men and is most often due to prostatism (now called lower urinary tract symptoms—LUTS) or bladder outflow obstruction. The patient may have noticed hesitancy (difficulty starting micturition—urination), followed by a decrease in the size of the stream of urine and terminal dribbling of urine. Strangury (recurrently, a small volume of bloody urine is passed with a painful desire to urinate each time) and pis-en-deux/double-voiding (the desire to urinate despite having just done so) may occur.

Renal calculi can cause ureteric obstruction (

Phleboliths (calcifications related to blood vessels) are rounded opacities seen in the pelvis below the level of the ischial spines, whereas ureteric calculi lie above this level, in the line of the ureters. The large staghorn calculus shown here is occupying the calyces of the left renal pelvis. This type of calculus is almost always radio-opaque. An abdominal ultrasound examination (IVPs are almost never performed in this context today) is necessary to check whether there is an obstruction at the pelviureteric junction. In general, 90% of renal calculi are radio-opaque and visible on plain X-ray films. A significant proportion of patients presenting with renal colic due to calcium calculi have hyperparathyroidism.

Table 7.5 Causes of acute renal failure (acute kidney injury, AKI

| a. Onset over days |

| This is defined as a rapid deterioration in renal function severe enough to cause accumulation of waste products, especially nitrogenous wastes, in the body. Usually the urine flow rate is less than 20 mL/hour or 400 mL/day, but occasionally it is normal or increased (high-output renal failure). |

| Prerenal |

| Fluid loss: blood (haemorrhage), plasma or water and electrolytes (diarrhoea and vomiting, fluid volume depletion) |

| Hypotension: myocardial infarction, septicaemic shock, drugs |

| Renovascular disease: embolus, dissection or atheroma |

| Increased renal vascular resistance: hepatorenal syndrome |

| Renal |

| Acute-on-chronic renal failure (precipitated by infection, fluid volume depletion, obstruction or nephrotoxic drugs)—see |

| Acute renal disease: |

| Acute tubular necrosis secondary to: |

| Tubulointerstitial disease: |

| Vascular disease: |

| Myeloma |

| Acute pyelonephritis (rare) |

| Postrenal (complete urinary tract obstruction) |

| Urethral obstruction: |

| At the bladder neck: |

| Bilateral ureteric obstruction: |

| b. Causes of rapidly progressive renal failure (onset over weeks to months) |

| Urinary tract obstruction |

| Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis |

| Bilateral renal artery stenosis (may be precipitated by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use) |

| Multiple myeloma |

| Scleroderma renal crisis |

| Malignant hypertension |

| Haemolytic uraemic syndrome |

Note: Anuria may be due to urinary obstruction, bilateral renal artery occlusion, rapidly progressive (crescentic) glomerulonephritis, renal cortical necrosis or a renal stone in a solitary kidney.

* Levin A, Warnock D, Mehta R, Kellum J, Shah S, Melitoris B, Ronco C. Improving outcome for AKI. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50(1):1–4.

Urinary incontinence

This is the inability to hold urine in the bladder voluntarily. It is not a consequence of normal ageing alone. The problem can occur transiently with urinary tract infections, delirium, excess urine output (e.g. from the use of diuretics), immobility (because patients are unable to reach the toilet), urethritis or vaginitis, or stool impaction.

Causes of established urinary incontinence include: (i) stress incontinence (instantaneous leakage after the stress of coughing or after a sudden rise in intra-abdominal pressure of any cause)—this problem is more common in women due to vaginal deliveries or an atrophic vaginal wall postmenopause causing a hypermobile urethra; (ii) urge incontinence (overactivity of the detrusor muscle) which is characterised by an intense urge to urinate and then leakage of urine in the absence of cough or other stressors—this occurs in men and women; (iii) detrusor underactivity—this is rare and is characterised by urinary frequency, nocturia and the frequent leaking of small amounts of urine from neurological disease; (iv) overflow incontinence (urethral obstruction)—this occurs typically in men with disease of the prostate, and is characterised by dribbling incontinence after incomplete urination; and (v) a vesico/urethral fistula—a complication of obstructed labour.

Chronic renal failure (chronic kidney disease)

The clinical features of chronic renal failure can be deduced in part by considering the normal functions of the kidneys.

Adequacy of renal function is defined by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). This is the volume of blood filtered by the kidneys per unit of time. The normal range is 90–120 mL/min. The GFR is estimated by calculating the clearance of creatinine (a normal breakdown product of muscle) from the blood. The serum creatinine and urea levels also provide a measure of accumulation of uraemic toxins and therefore of renal function. Most laboratories now provide an estimated GFR (eGFR) measurement calculated from the serum creatinine and the patient’s age and sex.

A new definition and classification of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been introduced. CKD is defined as kidney damage or GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or more, irrespective of cause.

Table 7.6 Classification of chronic kidney disease by glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

| Stage | Description | GFR (mL/min/1.73 m3) |

| – | Increased risk for chronic kidney disease (e.g. diabetes, hypertension) | >90 |

| 1 | Kidney damage but normal GFR | >90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage and mild GFR reduction | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderate reduction in GFR | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severe reduction in GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Kidney failure | <15 |

A uraemic patient may present with anuria (defined as failure to pass more than 50 mL urine daily), oliguria (less than 400 mL urine daily), nocturia (the need to get up during the night to pass urine) or polyuria (the passing of abnormally large volumes of urine) (

The more general symptoms of renal failure include anorexia, vomiting, fatigue, hiccups and insomnia. Pruritus (a general itchiness of the skin), easy bruising and oedema due to fluid retention may also be present. Other symptoms indicating complications include bone pain, fractures because of renal bone disease, and the symptoms of hypercalcaemia (including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation, increased urination, mental confusion) because of tertiary (or primary) hyperparathyroidism.

Find out whether the patient is undergoing dialysis and whether this is haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. There are a number of important questions that must be asked of dialysis patients (

Questions box 7.2

Questions to ask the dialysis patient

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Ask about any complications that have occurred, including recurrent peritonitis with peritoneal dialysis or problems with vascular access for haemodialysis.

A common form of treatment for renal failure is renal transplantation. A patient may know how well the graft is functioning, and what the most recent renal function tests have shown. Find out whether the patient knows of rejection episodes, how these were treated, and if there has been more than one renal transplant. It is necessary to ascertain if there have been any problems with recurrent infection, urine leaks or side-effects of treatment. Long-term problems with immunosuppression may have occurred, including the development of cancers, chronic nephrotoxicity (e.g. from cyclosporin or tacrolimus), obesity and hypertension from steroids, or recurrent infections. The patient should be aware of the need to avoid skin exposure to the sun and women should know that they need regular Papanicolaou

Menstrual and sexual history

A menstrual history should always be obtained. The menarche or date of the first period is important (

Vaginal discharge can occur in patients with infections of the genital tract. Sometimes the type of discharge is an indication of the type of infection present. The history of the number of pregnancies and births is relevant: gravidity refers to the number of times a woman has conceived, while parity refers to the number of babies delivered (live births or stillbirths). One should also ask about any complications that occurred during pregnancy (e.g. hypertension).

The sexual history is also relevant.

Treatment

A detailed drug history must be taken. Note all the drugs, including steroids and immunosuppressants, and their dosages. In patients with decreased renal function, the dosages of many drugs that are cleared by the kidneys must be adjusted. The patient with chronic renal failure should be well informed about the need for protein, phosphate, potassium, fluid or salt restriction. Patients with urinary tract infections may have had a number of courses of antibiotics. Treatment of hypertension should be documented. Certain drugs should be used with caution. For example, non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs can worsen renal function or cause CKD.

Past history

Find out whether there have been previous or recurrent urinary tract infections or renal calculi. There may have been operations to remove urinary tract stones, or pelvic surgery may have been performed because of urinary incontinence in women or prostatism in men. The patient may know about the previous detection of proteinuria or microscopic haematuria at a routine examination. Glomerulonephritis will usually have been diagnosed by renal biopsy, a procedure that is often a memorable event. History of other urological disorders and results for prior urological evaluations are important. Histories of diabetes mellitus or gout are relevant, as these diseases may lead to renal complications. It is most important to find out about hypertension, because this may not only cause renal impairment but is also a common complication of renal disease. Similarly, a history of acute kidney failure episodes, history of cancer treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, severe allergic reactions, and exposures to nephrotoxic substances are all relevant. A history of childhood enuresis (bedwetting) beyond the age of three years may be relevant: it can be associated with vesicoureteric reflux and subsequent renal scarring.

Ask about previous myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or valvular heart disease and about liver disease, especially hepatitis and about other systemic infections. Renovascular disease is more likely if there is a history of vascular disease elsewhere, such as myocardial ischaemia or cerebrovascular disease. In elderly patients, specific questions relating to ingestion of Bex or Vincent’s powders may suggest a diagnosis of analgesic nephropathy. This is particularly important as these patients require surveillance for urothelial malignancy in addition to managing their renal impairment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree