The Evolving Science of Dietary Supplements1

Christine A. Swanson

Paul R. Thomas

Paul M. Coates

1Abbreviations: AER, adverse event report: AMRM, Analytical Methods and Reference Materials; ATBC, Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; DSHEA, Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; NCCAM, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS, National Health Information Survey; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NVNMS, nonvitamin nonmineral supplements; ODS, Office of Dietary Supplements; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SRM, standard reference material.

Dietary supplements are a heterogeneous group of products that contain one or any combination of nutrients, herbs, and various other ingredients derived primarily from natural sources, from which they are extracted or chemically synthesized and then manufactured into finished products. Widely available for purchase without a prescription, dietary supplements are sold as capsules, tablets, liquids, and myriad other forms. Supplements and, increasingly, conventional foods containing supplement ingredients are often promoted as providing potential health benefits beyond basic nutrition.

Supplementation of the diet is not a new concept. By the early part of the twentieth century in the United States, cod liver oil and its concentrates were a marketed source of supplemental vitamins A and D. Supplements providing these and other nutrients became available in grocery stores in the mid-1930s, and the first multivitamin tablets were introduced in the early 1940s (1, 2). The number and diversity of dietary supplement products have grown enormously to include nonnutrients, so that today, tens of thousands of products are estimated to be available, with total sales exceeding $30 billion in 2011 in the United States alone (3).

In the United States, dietary supplements are primarily overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as are drugs and most foods. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 created the first regulatory structure for this class of products. Dietary supplements were legally defined as products containing vitamins, minerals, herbs or botanicals, amino acids, “a dietary substance … to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake [e.g., enzymes or tissues from organs or glands],” or “a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination” of any of these ingredients (4). They are further described as being intended for ingestion, not to be represented as a conventional food or as a sole item of a meal or diet, and must be labeled as a dietary supplement. Further details about FDA’s responsibilities for regulating dietary supplements and manufacturers’ responsibilities for marketing them are available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/default.htm (5).

Under the DSHEA, dietary supplements are considered to be foods and therefore require no formal preapproval by FDA. However, manufacturers proposing to use a “new dietary ingredient” must notify FDA before marketing. Because they are not drugs, dietary supplement products may not be promoted as a preventive, treatment, or cure for any specific diseases or conditions (6). Once purchased, however, consumers may use them for such purposes. The Federal Trade Commission regulates and monitors the advertising of dietary supplements in the marketplace (7).

In the United States, dietary supplements are often used as part of personal, proactive health care practices to ensure adequate intake of nutrients, maintain health, prevent illnesses, and in some cases to treat or manage various health problems and diseases, some minor (e.g., mild indigestion) and others that require medical supervision. The use of dietary supplements is considered by some consumers and health practitioners to be essential for achieving optimal health, together with attention to nutrition, fitness, stress management, and emotional and spiritual development. Supplements are often recommended to patients by practitioners of conventional medicine and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The latter group tends to emphasize holistic health care and often includes naturopaths—medical doctors who emphasize “natural” remedies.

Many of today’s dietary supplements contain ingredients derived from medicinal plants that have been used for millennia by people throughout the world, particularly in medical systems such as traditional Chinese medicine, Indian Ayurveda, and Arabic Unani medicine (8). Garlic (Allium sativum L.), for example, has been eaten as a food, used as a spice, and in more recent times taken as a supplement by consumers in the hope of reducing blood pressure and blood cholesterol levels. The world’s poorest populations still rely on herbs as medicines in primary health care (9).

Health care providers should ask their patients what dietary supplements they are taking, including herbal products. Unfortunately, most conventional medical practitioners and naturopaths in the United States have inadequate knowledge of the history, evidence base, and appropriate use of herbal medicines. The application of this practice, once embraced by eminent pharmacologists with an appreciation of pharmacognosy, involves expertise in a diverse and challenging array of disciplines ranging from ethnobotany to contemporary methods of natural products chemistry. Other indispensible skills include plant biochemistry, including an appreciation of the role and function of secondary plant metabolites and their pharmacology when administered to humans (10). Many of these secondary plant metabolites have been developed into pharmaceuticals widely used today (11). Plants with potential medicinal properties contain numerous bioactive constituents and can have beneficial, adverse, or no observable health effects. By emphasizing a multidisciplinary scientific framework for studying phytomedicinals, it is feasible that “rationale phytotherapy” as described by Varo Tyler (12) may someday reemerge as a wellrespected discipline in the United States and also return to western European countries, where it once flourished.

DIETARY SUPPLEMENT USE IN THE UNITED STATES

Dietary supplement use in the United States is assessed by large, nationally representative, cross-sectional surveys. The gold standard of surveys into the health status and health-related behaviors of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population is the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). It incorporates assessment methods designed to measure exposure to dietary supplement ingredients and has monitored supplement use since the 1970s. Prevalence data are collected to assess exposure of populations to nutrient and nonnutrient ingredients. Although sales data suggest increased use of specific ingredients, survey data provide the only means of quantifying supplement exposures and describing use by various population groups (e.g., children, pregnant women, elderly people).

National Surveys

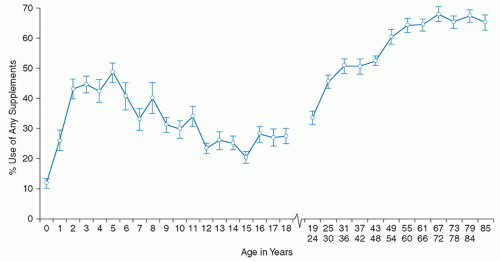

The first comprehensive information about supplement use by the US population after the DSHEA came from NHANES data collected from 1999 to 2002 (13, 14). Interviewers asked about supplement use (prescription and nonprescription) in the previous month, and most participants provided their supplement containers, from which ingredient and dosage information was taken from the label. Prevalence of use of any supplement among infants, children, and adults is shown in Figure 114.1.

Use of supplements was lowest among infants, increased through age 5 years, and then declined throughout adolescence. Nearly one-third of children took at least one dietary supplement, and most used multivitamins with or without minerals. Supplement use likely contributed substantially to total nutrient intakes (14). Use of supplements containing single botanical ingredients (e.g., echinacea) was minimal, similar to findings of another populationbased survey of children (15).

The increasing linear trend in supplement use among adults aged 19 to 65 years was followed by a plateau (13). Fifty-two percent reported supplement use in the following rank order: multivitamins with or without minerals (35%), calcium plus calcium-containing antacids (35%), vitamins E and C (12% to 13%), and B-complex vitamins (5%). Among supplement users, the majority reported daily intake, and about half reported taking only one product. Compared with the 1988 to 1994 NHANES, supplement use among adults increased substantially. The use of botanic products containing single herbs was minimal.

The National Health Information Survey (NHIS), another periodic survey of a nationally representative sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States, is a primary source of information about use of CAM. It, like NHANES, is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 1988, NHIS has included questions about use of nonvitamin nonmineral supplements (NVNMS), defined as products without vitamins or minerals. The 2007 survey found that almost 18% of adults and 4% of children had used NVNMS over the previous 30 days (16). Among adults, the five most commonly used NVNMS were fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids, followed by glucosamine, echinacea, flaxseed, and ginseng. Children most commonly took echinacea, fish oil/ omega-3 fatty acids, combination herbal pills, and flaxseed products. Use of herbal products decreased between the 2002 and 2007 surveys, but the exposure periods differed

in the two surveys, thus adding some uncertainty about the observed change over time.

in the two surveys, thus adding some uncertainty about the observed change over time.

Supplement Contributions to Total Nutrient Intake

The use of nutrient-containing dietary supplements will help some individuals obtain recommended intakes of vitamins and minerals while leading others to consume more than needed amounts (or do both to the same individual, depending on the nutrient). Both these situations have been observed (17, 18). Although estimates of intake depend on the quality of food and dietary supplement databases, assessments of adequacy and excess intake also reflect the validity of the nutrient reference values used.

Exposure Assessment Methods

As is the case with dietary assessment methods for food intake, no standard approach exists for obtaining either qualitative or quantitative information about dietary supplement use. Accurate reporting of usual intake can be a complicated cognitive task (19). Given the variation in questions about supplement use, it is unlikely that respondents describe their supplement use in a standardized manner, so cross-study comparisons are difficult. Researchers themselves differ considerably in their approach to supplement classification, particularly for botanicals. In addition, many investigators fail to address the quantitative uncertainty associated with supplement exposure assessment (20, 21). Exposure is based on marketed products, which vary in composition across brands. Some researchers do not clarify whether default values or supplement-specific composition data have been used. Even when label information is obtained directly, accurate quantitative assessment is not ensured, because the label declarations are not usually based on validated methods of chemical analysis. The impact of these errors depends on how the data are used and interpreted. More recently, several federal agencies have collaborated to improve methods to assess dietary supplement use and measure exposure to ingredients in specific products more accurately (22).

Characteristics of Supplement Users

Surveys find that adult supplement users differ from nonusers in various demographic characteristics, lifestyle, and health status. Users are more likely to be female, older, more educated, of non-Hispanic white race or ethnicity, physically active, of normal weight or underweight, and more likely to report excellent or very good health (13, 23). Users of herbal supplements may differ from those who take only nutrient-containing supplements. Some evidence indicates, for example, that use of botanicals is associated with lack of insurance coverage and limited access to conventional health care (24).

DIETARY SUPPLEMENT QUALITY AND SAFETY

Consumers and regulatory agencies expect that contents listed on supplement labels should accurately reflect the contents of marketed products and that they are safe when used as directed. ConsumerLab.com, a company that has tested more than 2400 dietary supplement products for more than 11 years, finds approximately 1 in 4 with a quality problem, mostly because of an inadequate amount or substandard ingredients followed by contamination with heavy metals (25). In a similar vein, agencies funding research relevant to dietary supplements expect grant applicants to have the capacity to characterize proposed

interventions used in preclinical and clinical research properly. These expectations are defined by product quality, which is also essential for product safety.

interventions used in preclinical and clinical research properly. These expectations are defined by product quality, which is also essential for product safety.

Natural Product Quality

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree