Figure 13.1)

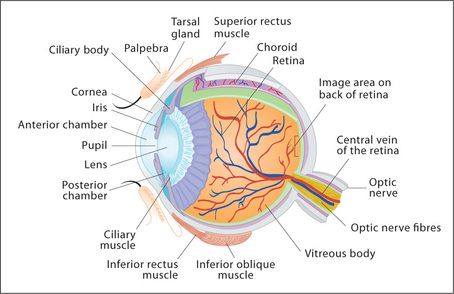

The structure of the eye is shown in

Examination method

Sit the patient at the edge of the bed. Stand well back from the patient at first, and note the following.

| The uveal tract consists of the anterior uvea (iris) and posterior uvea (ciliary body and choroid). |

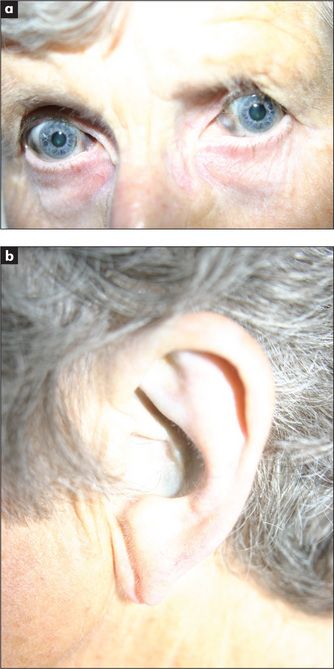

Figure 13.3 (a) Normal sclera (b) Conjunctival pallor in an anaemic patient

Note contrast between anterior and posterior parts in the normal eye.

Look from behind and above the patient for exophthalmos, which is prominence of the eyes. If there is actual protrusion of the eyes from the orbits, this is called proptosis. It is best detected by looking at the eyes from above the forehead; protrusion beyond the supraorbital ridge is abnormal. If exophthalmos is present, examine specifically for thyroid eye disease: lid lag (the patient follows the examiner’s finger as it descends—the upper lid lags behind the pupil), chemosis (oedema of the bulbar conjunctiva), corneal ulceration and ophthalmoplegia (weakness of upward gaze). Look then for any corneal abnormalities, such as band keratopathy or arcus senilis.

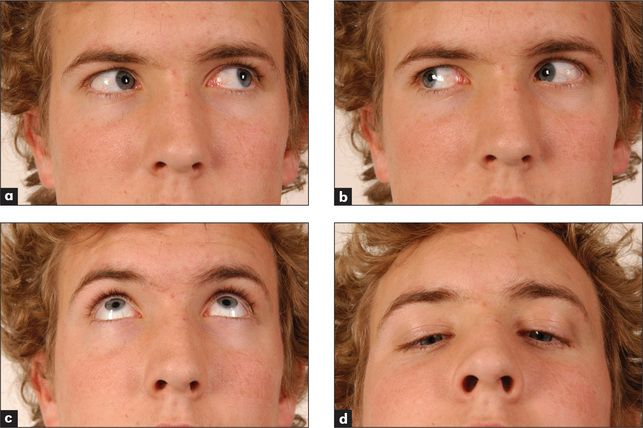

Figure 13.4 The cranial nerves III, IV & VI: voluntary eye movements

(a) ‘Look to the left.’ (b) ‘Look to the right.’ (c) ‘Look up.’ (d) ‘Look down.’

Begin by examining the cornea. Use your right eye to examine the patient’s right eye, and vice versa. Turn the ophthalmoscope lens to +20 and examine the cornea from about 20 cm away from the patient. Look particularly for corneal ulceration. Turn the lens gradually down to 0 while moving closer to the patient. Structures, including the lens, humour and then the retina at increasing distance into the eye, will swim into focus.

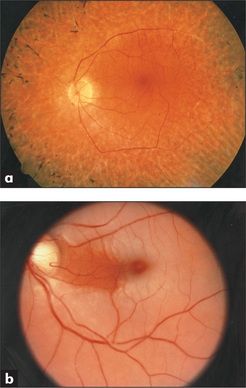

Examine the retinas (

There are four types of haemorrhages: streaky haemorrhages near the vessels (linear or flame-shaped); large ecchymoses that obliterate the vessels; petechiae, which may be confused with microaneurysms; and subhyaloid haemorrhages (large effusions of blood which have a crescentic shape and well-marked borders; a fluid level may be seen). The first two types of haemorrhage occur in hypertensive and diabetic retinopathy. They may also result from any cause of raised intracranial pressure or venous engorgement, or from a bleeding disorder. The third type occurs in diabetes mellitus, and the fourth is characteristic of subarachnoid haemorrhage.

There are two main types of retinal change in diabetes mellitus: non-proliferative and proliferative. Non-proliferative changes include: (1) two types of haemorrhages—dot haemorrhages, which occur in the inner retinal layers, and blot haemorrhages, which are larger and occur more superficially in the nerve fibre layer; (2) microaneurysms (tiny bulges in the vessel wall), which are due to vessel wall damage; and (3) two types of exudates—hard exudates, which have straight edges and are due to leakage of protein from damaged arteriolar walls, and soft exudates (cottonwool spots), which have a fluffy appearance and are due to microinfarcts. Proliferative changes include new vessel formation, which can lead to retinal detachment or vitreous haemorrhage.

Hypertensive changes can be classified from grades 1 to 4:

It is important to describe the changes present rather than just give a grade.

Inspect carefully for central retinal artery occlusion, where the whole fundus appears milky-white because of retinal oedema and the arteries become greatly reduced in diameter. This presents with sudden, painless unilateral blindness, and is a medical emergency.

Central retinal vein thrombosis causes tortuous retinal veins and haemorrhages scattered over the whole retina, particularly occurring alongside the veins (‘blood and thunder retina’). This presents with sudden painless loss of vision which is not total.

Retinitis pigmentosa causes a scattering of black pigment in a criss-cross pattern. This will be missed if the periphery of the retina is not examined.

In retinal detachment, the retina may appear elevated or folded. The patient describes a ‘shade coming down’, flashes of light or showers of black dots. A diagnosis requires immediate referral to try to prevent total detachment and irrevocable blindness.

White spots occur in choroiditis which when active have a fluffy edge (e.g. in toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis).

Finally, ask the patient to look directly at the light. This allows the examiner to locate and inspect the macula. Macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness; central vision is lost. Drussen formation occurs in macular degeneration—small deposits are seen under the epithelium in the central retina. Macular degeneration may occur secondary to an atrophic or neovascularisation process.

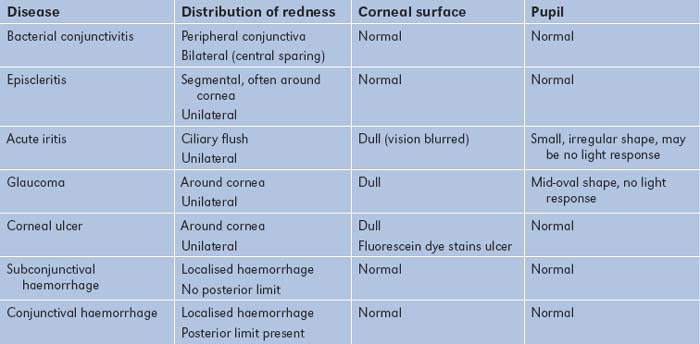

The causes of common eye abnormalities are summarised in

TABLE 13.3 Causes of eye abnormalities

CataractsStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|