The Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap for Breast Reconstruction

Robert J. Allen

Constance M. Chen

In 2009, almost 200,000 women in the United States received a breast cancer diagnosis. Of women who undergo surgical treatment, two-thirds elect to undergo breast-conserving treatment (BCT) while one-third elect to undergo mastectomy. For most women, the crucial element that drives their choice is trying to balance their concern about cosmetic results with their fear of recurrence. Thus, the ideal solution for most women faced with a breast cancer diagnosis would be to eliminate risk of breast cancer while preserving breast appearance.

In 2007, about 56,000 women in the United States underwent breast reconstruction— a rate that is double that of a decade earlier. Of these women, about 70% underwent breast reconstruction with tissue expanders and implants, while only about 30% underwent breast reconstruction with autologous tissue. Yet a 2009 University of Michigan study demonstrated that while there is no difference in short-term (<5 years) patient satisfaction after implant-based or autologous tissue breast reconstruction, over the long term (>9 years) there is significantly less patient satisfaction after implant-based breast reconstruction while patient satisfaction after autologous tissue breast reconstruction remains consistently high.

Of all the types of autologous tissue breast reconstruction, the current gold standard is perforator flap breast reconstruction. In particular, the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap breast reconstruction has achieved popularity as a consistent and reliable method of creating a long-lasting and natural-appearing breast with minimal patient morbidity. By using the skin and fat of the abdominal tissue to recreate the breast mound, the DIEP flap achieves the plastic surgery principle of “replacing like with like.”

The best candidates for DIEP flap breast reconstruction are women with adequate abdominal fat and no major medical comorbidities who have not previously undergone autologous tissue breast reconstruction. In particular, women who have undergone multiple pregnancies often experience a “tissue expander” effect on their abdominal skin and fat that renders their abdomen an ideal donor site for DIEP flap breast reconstruction. The abdominal fat must incorporate an adequate blood supply from the deep inferior epigastric vessels, however. Thus, women who have undergone abdominoplasty are not candidates for DIEP flap breast reconstruction, as the perforators from the deep inferior epigastric vessels will have been taken. Likewise, women who have undergone gynecological exenterations or extensive intra-abdominal procedures should also obtain preoperative imaging prior to a DIEP flap breast reconstruction to ensure that the perforating vessels from the deep inferior epigastric vessel are still intact. Liposuction is not an absolute contraindication to DIEP flap breast reconstruction, but very thin women with no abdominal fat may not have enough subcutaneous tissue to recreate a satisfactory breast mound. If a woman does not have adequate abdominal fat for a DIEP flap breast reconstruction, she may still be able to undergo autologous tissue breast reconstruction using either the medial thigh or the buttock as donor sites.

Another common indication for DIEP flap breast reconstruction is failed implant-based breast reconstruction. About 25% of our breast reconstruction patients are women who have experienced problems such as infection, capsular contracture, implant displacement, or other such problems after implant-based breast reconstruction. Particularly in women who have had to undergo radiation therapy as an adjunct to their breast cancer treatment, autologous tissue breast reconstruction can create a new breast mound that looks and feels natural while using the womanís own tissues.

Besides abdominoplasty, the primary contraindications to DIEP flap breast reconstruction are severe medical comorbidities. For example, significant heart disease, pulmonary disease, or other systemic disease may preclude any reconstructive effort. Breast reconstruction is an elective operation and, despite its significant psychological benefits, should not endanger the welfare of a patient. Other risk factors in the medical history that should influence decision making include diabetes, autoimmune disease, obesity, previous history of abdominal surgery, and prior radiation therapy. Additionally, smoking has been found to be significantly associated with overall complications. Active smokers should be counseled to abstain from tobacco and nicotine use for a minimum of 4 weeks prior to any reconstructive procedure. For potential postmastectomy radiotherapy patients, it may be prudent to place a tissue expander as a skin spacer or to delay reconstruction to avoid the complications that can result from irradiating a free flap.

All patients require an extended preoperative consultation to delineate goals, explain alternatives, discuss expectations, and review potential complications. In doing so, the patient becomes actively involved in the decision-making process and participates in the selection of a reconstructive technique.

During the initial consultation, potential patients gain an understanding that DIEP flap breast reconstruction involves three stages. The first stage involves actual microsurgical breast reconstruction with the DIEP flap. In a unilateral breast reconstruction, a symmetrizing procedure on the contralateral breast such as mastopexy, augmentation, or reduction may be performed at either the first or second stage. The second stage involves nipple reconstruction and any revision to the donor site, breast flap, or the contralateral breast in a unilateral reconstruction. For example, any excess tissue at the donor site or fat necrosis in the breast flap may be excised at this time. The third stage involves tattooing of the nipple–areolar complex. The first stage is an inpatient procedure that requires an average hospital stay of 3 to 4 days. The second stage is performed as an outpatient procedure in the hospital or in the office. The third stage is always performed in the office. Increasingly, some patients are candidates for nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate DIEP flap breast reconstruction. In these patients, DIEP flap breast reconstruction is performed as a one-stage procedure, with no subsequent stages necessary.

Suitable patients who elect DIEP flap breast reconstruction undergo routine presurgical testing, including appropriate

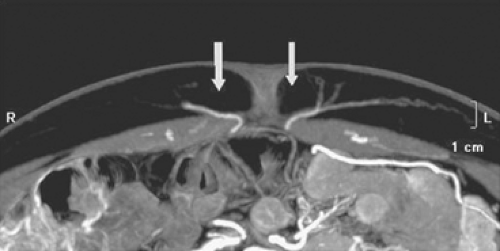

laboratory and diagnostic studies and anesthesia consultation. Blood typing and screening is not necessary. We routinely obtain preoperative imaging—either computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)— to delineate the topography of the DIEPs. We find that preoperative imaging reduces our operative time by about 1 hour, and it also contributes greatly to patient safety as we are confident about exactly which perforating vessels will be the largest and most robust to use for the DIEP flap. We are able to plan the course of our dissection preoperatively, and we do not waste time guessing which perforating vessels to use while the patient is under general anesthesia.

laboratory and diagnostic studies and anesthesia consultation. Blood typing and screening is not necessary. We routinely obtain preoperative imaging—either computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)— to delineate the topography of the DIEPs. We find that preoperative imaging reduces our operative time by about 1 hour, and it also contributes greatly to patient safety as we are confident about exactly which perforating vessels will be the largest and most robust to use for the DIEP flap. We are able to plan the course of our dissection preoperatively, and we do not waste time guessing which perforating vessels to use while the patient is under general anesthesia.

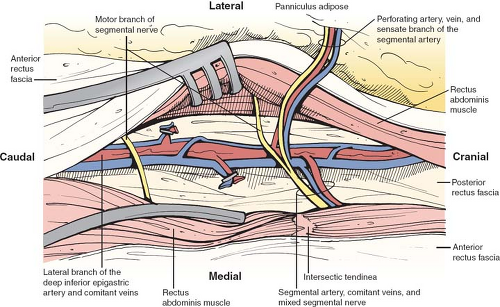

Detailed knowledge of the deep inferior epigastric vasculature and its perforator topography is relevant for successful execution of the DIEP flap. Accurate knowledge of the perforator topography may be obtained via preoperative imaging—either CTA or MRA. The largest perforator vessels may be chosen preoperatively, and then mapped on an X–Y axis. The ideal perforator vessel is at least 2 mm in diameter with a short intramuscular course. In 8% of patients, a septocutaneous perforator may be found in which the dominant perforator vessel travels around the medial edge of the rectus abdominis muscle with no intramuscular course at all (Fig. 1). This completely eliminates any intramuscular dissection and damage to the musculature, and the best way to identify a septocutaneous perforator is via preoperative imaging (Fig. 2). Often, the best perforator vessels are around the umbilicus or slightly above the umbilicus. In these situations, we design our DIEP flap to incorporate the largest and most robust perforator vessels as seen on preoperative imaging.

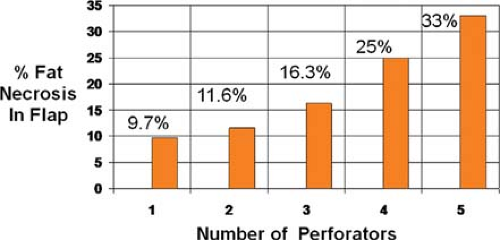

Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated that the incidence of any complication increases with the number of perforator vessels used (Fig. 3). For example, univariate analysis of partial flap loss indicated significance of any complication with use of five perforators (P <0.05). Both univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated significantly fewer complications with use of one perforator (P <0.05). For fat necrosis, there was no statistically significant incidence of complications with five perforators, but there was a steady trend of increased incidence of fat necrosis with increasing number of perforators (P < 0.05). Thus, we believe that it is generally best to harvest one perforator for a DIEP flap, as long as the single perforator chosen is the best perforator. Ideally, this is delineated on preoperative imaging and confirmed with intraoperative clinical judgment.

The DIEP flap is based on the perforating vessels that originate from the deep inferior epigastric system. These perforators travel through or around the rectus abdominis muscle, pierce the anterior rectus sheath, and supply the overlying skin and fat (Fig. 4). During DIEP flap surgery, the lower abdominal soft tissue is mobilized on one or more perforators in preparation for free tissue transfer. Since the rectus abdominis muscle is not harvested, the pedicle length is substantially longer than in a TRAM flap. The longer pedicle length makes the DIEP flap easier to position in the chest wall and also simplifies the microsurgical anastomosis.

Patients are marked preoperatively in the standing position for anatomic landmarks on the breast and abdomen (Figs. 5 and 6). On the anterior chest wall, this includes the boundaries of the existing breast mound. On the lower abdomen, marks are placed at the midline, perimeter of the umbilicus, and proposed outline of an elliptical flap in the hypogastrium. The upper mark of this proposed flap is placed above the umbilicus to incorporate paraumbilical perforators. The lower mark is placed in a suprapubic crease, and may be shifted superiorly during surgery to ensure tension-free closure of the abdomen.

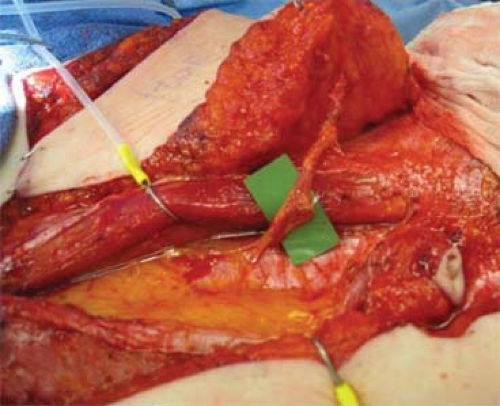

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the arms at 60 degrees or tucked by the side, depending on the surgeonís preference. We prefer to have the arms tucked, unless the breast surgeon needs to have the arms extended for a lymph node dissection. Simultaneous abdominal flap harvest and preparation of the chest wall vasculature is carried out with a two-team approach. The internal mammary system is used as a recipient site. The

vessels are usually approached at the level of the third rib and in the interspace above or below it, depending on which interspace has the greatest width (Fig. 7). The diameter of the internal mammary vessels usually increases as it travels inferiorly. When technically feasible, we always try to use a rib-sparing technique and preserve the pectoralis muscle to prevent a chest wall deformity. Occasionally, the internal mammary system may have adequately sized perforators that can be used for microanastomosis, thus precluding the need to dissect through the rib space to the deeper internal mammary vessels.

vessels are usually approached at the level of the third rib and in the interspace above or below it, depending on which interspace has the greatest width (Fig. 7). The diameter of the internal mammary vessels usually increases as it travels inferiorly. When technically feasible, we always try to use a rib-sparing technique and preserve the pectoralis muscle to prevent a chest wall deformity. Occasionally, the internal mammary system may have adequately sized perforators that can be used for microanastomosis, thus precluding the need to dissect through the rib space to the deeper internal mammary vessels.

Increasing numbers of microsurgeons who routinely perform perforator flap breast reconstruction identify the main perforators of the deep inferior epigastric vasculature preoperatively via CTA or MRA. This allows them to obtain precise information on perforator diameter and three-dimensional course. Some use a handheld Doppler probe to confirm the vessels that they choose preoperatively, and then identify them with direct visualization during flap harvest and perforator isolation.

Harvesting of the DIEP flap begins with an incision at the upper marked line, dissection through the full thickness of the abdominal wall to the anterior fascia, and elevation of a superior abdominal wall flap. If the perforator has already been identified via preoperative imaging, then the dissection can continue directly to the chosen perforator. In a bilateral DIEP flap, the midline incision is made first. If the perforator is a medial row or a septocutaneous perforator, then the chosen perforator is isolated prior to elevating the lateral edges of the abdominal flap. Mobilization continues to the xiphoid process and the costal margins, as in a standard abdominoplasty. The upper flap may be mobilized inferiorly to confirm ease of closure of the preoperatively marked donor site. A shifting of the lower marked line superiorly may be required to allow for primary closure of the abdomen. Once the largest perforator has been identified, the dissection proceeds efficiently with elevation of the skin-fat flap from the underlying rectus fascia. The remainder of the perforators are ligated and divided. Care is taken when making the inferior incision to look for superficial inferior epigastric vessels. In particular, it is helpful to preserve the superficial inferior epigastric vein in case the flap has a superficial-dominant drainage system.

Isolation of the DIEP flap proceeds under loupe magnification, and begins by opening the anterior rectus sheath around

the selected perforator. Some surgeons incorporate a 1- to 2-mm cuff of the sheath around each perforator, but routinely, no fascia is harvested. Using a Westcott microsurgical scissor or bipolar electrocautery, the perforator is followed through the rectus muscle, carefully ligating and diving all small side branches with microsurgical gem clips. Bipolar electrocautery can be used for the smallest of branches. If a second or third perforator has been selected, particular attention must be paid to maintaining its continuity in line with the first. Preoperative imaging is very helpful in determining the vascular course. Occasionally, it can also be helpful to elevate the lateral or medial edge of the rectus abdominis muscle to identify the deep inferior epigastric pedicle on the underside of the rectus and follow it in a retrovascular fashion.

the selected perforator. Some surgeons incorporate a 1- to 2-mm cuff of the sheath around each perforator, but routinely, no fascia is harvested. Using a Westcott microsurgical scissor or bipolar electrocautery, the perforator is followed through the rectus muscle, carefully ligating and diving all small side branches with microsurgical gem clips. Bipolar electrocautery can be used for the smallest of branches. If a second or third perforator has been selected, particular attention must be paid to maintaining its continuity in line with the first. Preoperative imaging is very helpful in determining the vascular course. Occasionally, it can also be helpful to elevate the lateral or medial edge of the rectus abdominis muscle to identify the deep inferior epigastric pedicle on the underside of the rectus and follow it in a retrovascular fashion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree