Production Disorders versus Reception Disorders

This classification would seem to follow on nicely from the communication chain model presented in Chapter 3. But it should be plain, following our discussion of feedback (p. 74), that such a classification is very much a simplification. A purely auditory deficit can, and invariably does, lead to major problems of production, as we shall see in our discussion of deafness (p. 209). A purely production problem, such as stuttering, can raise difficulties of listening (see p. 192). And when we deal with disorders of the central nervous system, such as aphasia, or the psychopathological syndromes, it proves extremely difficult to disentangle the two. Aphasic patients are sometimes described as ‘receptive’ or ‘expressive’ (i.e. of production), as we shall see (p. 167); but the majority of aphasic patients have problems in both domains. Likewise, in children who have failed to develop language normally (see p. 172), the issue of whether there is primarily a production or reception problem may be unresolvable. The impairment of the brain systems responsible for the processing of language may result in such children experiencing difficulties in identifying the regularities in the language they hear around them, with consequences for both comprehension and production. The distinction between disorders of production and disorders of reception, then, is best seen as a rudimentary means of guiding, but never constraining, research and classification.

Organic Disorders versus Functional Disorders

This distinction is also commonly encountered in language pathology. It is a consequence of the priority given to the medical approach to analysis (compare Chapter 2) whereby disorders are divided into two broad types: those where there is a clear organic (anatomical, physiological, neurological) cause and those where there is not. Various terms are used to refer to the latter category (e.g. psychogenic, psychological), but the most widespread term is ‘functional’. So, for example, if a person loses the ability to make the vocal folds vibrate, and there is plainly a neurological cause for this (for example, damage to a recurrent laryngeal nerve), the voice disorder would be classified as organic (see further p. 197). On the other hand, if an ENT examination could establish no cause, it would be concluded that there were psychological reasons for the problem, and the diagnosis would be functional. Other disorders – for example, in articulation and fluency – can also be classified in this way. However, the apparently clear-cut nature of this division is misleading. Many disorders represent a combination of organic and psychological factors. A person who has suffered a stroke has a neurological cause of subsequent communicative difficulties, but if embarrassment at changed physical appearance and communication abilities leads to avoidance of social contacts, there is also a psychological element to the disorder. And this is so often the case; either it is plain that both types of factor are involved or it is unclear which of the two types is involved. Long and often acrimonious debate has taken place in the field of psychopathological disorders such as schizophrenia, autism and depressive illness regarding the weight that should be given to organic, as opposed to functional, components of disorders. There are also cases where we may classify a disorder as functional but by default. It may simply be that modern science does not yet possess the techniques by which organic causes to disorders can be identified. Some fluency disorders provide an example of this: it might be that some stutterers have deficits in neurophysiological functioning which remain, as yet, undetected.

Speech Disorders versus Language Disorders

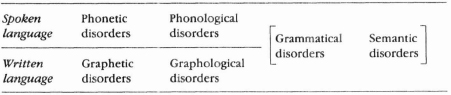

This classical distinction is still in widespread use, though with the application of ideas from linguistics its applicability has increasingly been questioned. The origins of the distinction lie in the difference between ‘symbolic’ and ‘non-symbolic’ aspects of communication. Certain aspects of communication have as their primary role the communication of meaning: they have a symbolic function. By contrast, other aspects of communication have no direct involvement with meaning; their presence is an incidental result of the choice of communicative medium; they do not affect the meaning at all (are ‘non-symbolic’). Grammar and vocabulary were considered to be the main symbolic factors in communication; and when speech was the medium of communication involved, it was the phonetic characteristics of speech which were considered to be non-symbolic. The former factors were grouped under the heading of language; the latter were grouped under the heading of speech. The position can be represented as follows:

| Speech | Language |

| Phonetics | Grammar |

| Semantics |

Under the heading of speech disorders, in its broadest sense, then, were placed any disturbances arising out of damage to the motor functions of the vocal organs – disorders in the anatomy, physiology or neurology of the systems concerned. In this general sense, disorders of voice production (see p. 194), fluency (see p. 188) and articulation (see p. 200) could all be subsumed as ‘speech disorders’, as in no case was the formulation of meaning affected, but only its transmission through the medium of sound.1 Under the heading of language disorders were grouped those disturbances which affected the formulation and comprehension of meaning – aphasia in particular (see p. 165), and also a wide range of developmental and psychological disorders.

There are several things wrong with this distinction. First, it gives exclusive emphasis to sound as a medium of communication, as opposed to the visual or tactile media – an understandable emphasis, of course (see p. 2), but a theoretically restricting one. Second, it apparently gives priority to the motor disorders of communication, as opposed to the sensory ones. Why is not hearing mentioned, being a category of disability comparable in generality to speech, in the above sense?2 Third, there is a confusion because of the everyday meaning of the term ‘speech’ to mean ‘spoken language’ – in which, inevitably, meaning is involved. Some textbooks on disability in fact use the term in this general sense, and thus constitute a quite different tradition from that referred to above. Fourth, there is considerable uncertainty over how to apply the model in several clinical conditions. This happens especially when the disorders in question involve the phonological component of language. Phonology is ‘mid-way’ between phonetics and the other levels of language organization (see p. 42). It has in fact often been called a ‘bridge level’ or ‘interlevel’. Because it constitutes the sound system of the language, it is intimately connected with the transmission of meaning: the fact that pin and bin are different in meaning is a consequence of the phonological opposition that distinguishes the words; and a similar point can be made about the non-segmental aspects of phonology (though here the relationship between sound and meaning is at times even more direct, as when we talk of the emotional role of intonation in speech). On the other hand, this level is intimately connected with phonetics, i.e. with the physical realization of sound through the use of the vocal organs. There are, as we have seen (p. 35), a wide range of possible realizations for a given phonological contrast, depending on the vagaries of our individual pronunciation habits. So the question is: how are we to classify disorders of the phonological system, whether segmental or non-segmental? Are they disorders of speech or of language?

The obvious answer would seem to be ‘both’, or ‘don’t know’. But whenever a question is unanswerable in this way, it is usually because the terms in which the question has been put are in some way irrelevant. Phonological disorders form a unique class in linguistic pathology; they should not be identified with the meaning-generating levels of language, nor should they be identified with the phonetic manifestations of language. A disorder of intonation, for example, being primarily a phonological problem, does not fit easily under the original headings of speech or language. A more satisfactory model of linguistic pathology will therefore be more along the lines of Figure 2.1, as re-presented in Table 5.1. The term ‘spoken language’, in this respect, is far more illuminating than ‘speech’, and preserves a useful parallelism with other media (compare ‘written language’, ‘signed language’).

Table 5.1. Main categories of linguistic pathology

Acquired Disorders versus Developmental Disorders

This classification is pervasive through much of language pathology. Its influence can be seen in the literature, the organization of clinical services, the structuring of language pathology courses and the development of clinical specialisms. Acquired disorders are those in which previously learned speech or language ability becomes impaired. A developmental disorder is one in which the acquisition of speech or language ability is impaired. The distinction rests on the loss of already acquired knowledge, in contrast to difficulties in acquiring this knowledge. An adult who suffers brain damage following a stroke or head injury, and who subsequently has difficulties in speech or language, demonstrates an acquired disorder. The child who is slow to learn language illustrates a developmental disorder.

The distinction is important in classifying disorders and it does have clinical implications. The language pathologist who works with a patient with a developmental disorder will be attempting to facilitate the patient’s learning of linguistic knowledge. The clinician who treats clients with acquired disorders may also be working in this way, but as these patients may not necessarily have lost all of their previously stored linguistic knowledge – rather, it is temporarily inaccessible – the clinician may be working to help patients re-access this knowledge. The evidence for temporary inaccessibility of knowledge comes from observations of variability in the performance of adults with brain lesions. The extent of this variability can at times be marked. One aphasic patient, whose speech usually consisted of unintelligible phonemic jargon (his output consisted of syllables which were not words of English – [‘boʊ i: ‘boʊ], for example), entered the clinic one day and asked his therapist ‘Can I have a new book please?’ – much to his own and the clinician’s astonishment. On being asked to repeat this same utterance, his output reverted to the more usual jargon, to the frustration of both parties.

Despite the clinical importance of the distinction between acquired and developmental disorders, the consequences of this classification are at times too pervasive. The language pathology literature – beyond the level of an introductory text such as this – is divided into books and research papers dealing with acquired disorders and those addressing issues in developmental disorders. Training courses for language pathology students are typically divided into developmental disorders and acquired disorders. Often the two types of disorders might be covered in different years of an academic programme, thus emphasizing the split and discontinuity between the two. Clinical services are organized into those dealing with developmental disorders (often termed a ‘paediatric’ service) and those working with acquired disorders (termed the ‘adult’ service).3 But we can question the value of this divide. It would suggest that the knowledge base and skills required of the different specialists are distinct; but is this really so? Both groups of clinicians need knowledge of normal language functioning – how language is organized and how it is processed. The physical basis of communication is common to both categories of disability, as are many of the general aspects of assessment and treatment – for example, the importance of holism. There are specialized techniques and knowledge which separate the two fields, but these are in danger of being overemphasized and the commonalities of being ignored. There are advantages if each of the developmental and acquired fields keeps a watch on changes in its fellow, thus permitting cross-fertilization of ideas and opportunities for theoretical and practical advances.

Language Deviance versus Language Delay

This is a classification of a rather different order, because it is generally applied only to cases of disorders in the acquisition of language by children. The term ‘deviant’ is here being used in a much narrower sense from that commonly encountered in language pathology. In its broadest sense, ‘deviant’ can be applied to any pathology, by definition – i.e. it means no more than ‘abnormal’. In the present context, however, it has a more restricted application, referring to the child’s use of structures, pronunciations, words etc. which are outside the normal patterns of development in children (and, we might add, which are also outside the normal range of adult possibilities for the dialect). For example, a child who said or wrote man the would be illustrating linguistic deviance, because this is not a possible or expected structure in the contexts just described. Similarly, a child who pronounced /h/ sounds as /k/ sounds would again be considered as showing deviant behaviour, as this is not one of the normal substitution processes involved in language acquisition (compare p. 202). Or again, a child who passed through the various stages of increasing complexity of language acquisition, but in the wrong order, would also be classed as displaying deviant behaviour. Against this, there is the notion of language ‘delay’, where the suggestion is that everything the child says is a normal developmental feature of language; it is simply that a time-lapse has taken place – the child should have been at that stage of development several months or years before. The delay may be in pronunciation, grammar, semantics, or in some combination of these three. An alternative way of putting it is that the language is still ‘immature’ for the child’s age.

This is quite a useful distinction but, as with the others reviewed in this chapter, it must not be adopted uncritically. Let us consider the notion of deviance. This is not a homogenous notion: there are many degrees and kinds of deviance, as we move from the area designated as ‘normal’. Let us take, for example, a child’s use of the /t/ phoneme in English. In a group of patients, a whole range of sounds might be substituted for the [t] which we would normally expect. A fairly predictable type of substitution is [k] – the child says /km/ for /tm/, and so on. Rather less predictable is [p], but we can at least see some possible reasons for the confusion (they are both voiceless plosives). Less predictable still is [s], [w], and [h] – but at least these are all sounds from the same dialect. Quite inexplicable would be a sound from outside the child’s dialect and apparently having nothing in common with [t] – such as the uvular trilled r (as in French). There are evidently degrees of deviance between these substitutions, though it is not always possible to give reasons as to why one sound should be more or less deviant than another. And a similar argument applies to a child’s deviant use of grammar or vocabulary. Which of the following two deviant sentences would you say was the more deviant (compare the examples on p. 219)?

cat the on be mat

going to the boy play

It is extremely difficult to decide; and deviant sentences, therefore, often have to remain unanalysed in a grammatical analysis of language disorders.

There are also complications within the notion of delay. If you take this notion literally, then the category probably does not exist. A ‘delayed’ child of 7 years of age would be interpreted to mean that exactly the range of linguistic habits is being displayed as we would expect to see in a younger child. This would mean that not only the qualitative range of the language reflected this less mature norm, but also the quantity of language would be that characteristic of the younger group. This rarely, if ever, happens. What we find is several different kinds of ‘unbalanced’ language delay – a delay which is mainly located under the heading of pronunciation, or of grammar, or of vocabulary – and if, say, grammar, then affecting certain aspects of grammar more than others (see further, p. 175). If such children were developing normally in all other domains they would also be wanting to ‘do’ several things with their language which younger children would not be doing, and this would add further differences. In diagnosing such children, therefore, an important step is the drawing up of as complete a profile of their linguistic abilities as possible, to establish to what extent and in what areas of language there are genuine delays. And in the course of doing this, we may well encounter deviance as well as delay – a ‘mixed’ category of patient, once again.

Abnormal versus Normal

Underlying much of this discussion is an assumption which itself is not immune from criticism – the idea that it is possible to draw a clear dividing line between the concepts of normality and abnormality. Of course, this is a distinction with which everyone attempts to work, despite the unhappy overtones which the term ‘abnormal’ carries. (But notice that ‘abnormality’ means ‘significantly different from normal or from the average’, a definition which encompasses idiosyncrasy, eccentricity or brilliance.) There is likely to be a gradient between the two (as already seen, in the notion of deviance), and the decision as to whether a behaviour is normal or abnormal will often be very difficult to make. But there are certain useful guidelines to be obtained from a consideration of this distinction.

The concept of abnormal is plainly dependent on some kind of prior recognition being given to the notion of normal (compare p. 7). One would not teach ENT pathology on a speech pathology course, for instance, until a basic understanding of the normal anatomy and physiology had been established. But this point is not quite as obvious as it sounds, when it comes to linguistic studies. Let us imagine a child who has been identified as having ‘abnormal’ language behaviour turning up at a clinic. An assessment must be carried out, and the nature of the abnormality pinpointed. But with what norm should the child be compared? How should the child be speaking? The language pathologist will need to know the dialect that the child’s family and peers use, in case there are differences between the way the clinician speaks and the way the child will be expected to speak by parents and peers. It will be important to know how much language the child should have acquired for his or her age. The child’s sex will also be a factor here (in some areas of language, the rate of acquisition in girls is faster than that in boys), as will social background (there are differences in the expectations parents have about their children’s language, and this may relate to differences in social class).4 It will also be necessary to know how rapidly children of the patient’s age (sex, etc.) generally pick up new language, in order to evaluate whether the child’s response to language treatment is normal.

If only we were all in the position of having fully mastered knowledge about these norms! Unfortunately, the real world is a long way away from the ideals of the previous paragraph. Some norms are fairly well established (e.g. grammatical norms of development up to age 4 or so), but others have received little scientific study (e.g. the detailed difference between rates of development for boys and girls). And the more ‘exceptional’ the patient, the less likely there will be information about norms. As soon as we consider the special problems of immigrants, bilinguals, physically disabled, and other ‘exceptional’ groups, the size of the problem should be apparent.

Before we leave these terminological issues, there is one further area that needs to be addressed. The choice of terms to refer to certain disabilities – such as mental handicap or deafness – is always a sensitive issue. The problem is one of what is commonly called ‘political correctness’, or the use of language in an ideologically correct way – that is, an ideology which suggests that the disabled should not be excluded from society or construed in negative or stigmatizing ways. Over the past two decades there has been a mushrooming of pressure groups whose aims are to raise the profile of individuals with disabilities and to counter the marginalization of these individuals from society. A concern of these groups has been with the terms society uses to refer to individuals with disabilities, some of which are claimed to be demeaning. These concerns are illustrated by a debate which has been taking place in Great Britain within the charity ‘MENCAP’, which represents the interests of the mentally handicapped. MENCAP’s name is derived from the term ‘mentally handicapped’ – a label which some people have come to regard as unsatisfactory. The suggestion is to replace it by ‘learning disability’ or even ‘intellectually challenged’. Changes of this kind present authors of introductory textbooks on disability with huge problems. Failure to use the current term may disappoint readers who are knowledgeable in a particular area; but use of fashionable neologisms may leave the novice reader confused.

An additional problem with changes in terminology is that this is a perpetual process. The term ‘mental handicap’ was once an approved term, replacing labels such as ‘educationally subnormal’. ‘Educationally subnormal’ was also once an approved term, replacing the labels which emerged from the early days of intelligence testing, such as ‘idiot’. What we are seeing here is a process of euphemism. Some topics in a society are viewed by a large number of individuals as taboo – people do not like to talk about them – and the negative connotations which are attached to the subject transfer to the words that are used to refer to them. In a situation where the issue has to be addressed, therefore, a polite form of euphemism is used. The problem is that the negative connotations eventually attach to the euphemism, thus spurring the creation of a new term. This process is aptly illustrated by the observation that ‘LD’, the acronym for learning disability, has emerged as an insult in the playgrounds of Britain. In the following sections, in which we describe how the communication chain may be disrupted, we shall try to present terms that are familiar to the student new to the field, but also point out variations in terminology of this kind.

Disruptions of the Communication Chain

The remainder of this chapter reviews the chief characteristics of the major categories of linguistic pathology. We shall follow the direction of the communication chain, beginning with disorders of message encoding. The communication chain is presented again in Table 5.2, but this time the labels of disorders representing impairments at each level are also included. Presenting a review of disorders in this way does have its dangers: the reader may come to view each disorder as isolatable at a single level of the communication chain. It is therefore necessary to remember that a disruption at one point in the chain may lead to difficulties in others. A hearing impairment will lead to impaired efficiency in receiving acoustic messages, but this will also reduce the efficiency of auditory feedback mechanisms in speech – potentially causing speech production difficulties – as well as difficulties in receiving spoken messages. This can in turn lead to comprehension failures and, if the hearing-impaired individual is a young child, to difficulty in receiving sufficient auditory input to permit easy language learning. Similarly, a group of disorders which we have linked together as language disorders commonly display difficulties in learning or using a language system both to encode and to decode linguistic messages. Any patient with such a disorder will have difficulties at both ends of the communication chain – in sending and receiving linguistic messages. With this qualification in mind, we can proceed to the first of our categories of communicative pathology.

Pre-linguistic pathologies

Disorders which represent disruptions of the pre-linguistic stage are grouped together under the heading of ‘cognitive disorders’. This title is not entirely adequate for two reasons. First, although many of the disorders included within this category – for example, dementia – do represent very serious disabilities in the processing of information, they also result in much broader impairments of personality, emotion and social competence. Second, it suggests that cognition is in some way entirely separable from language, and that disorders grouped under this heading represent a failure solely at the pre-linguistic level. Neither point is entirely valid, as we shall see. However, the grouping is still of value, because it emphasizes that individuals suffering from these disorders are likely to have difficulties in a broad range of abilities; that is, their difficulties will extend beyond language.

Table 5.2. Disruptions of the communication chain

| Stage | Disorder |

| Pre-linguistic | Cognitive disorders Thought disorders Autism Learning difficulties |

| Language encoding | Language disorders Aphasia Developmental language disorders |

| Motor programming | Apraxia |

| Motor execution | Dysanhria |

| Disorders of voice e.g. vocal misuse, laryngectomy | |

| Disorders of fluency e.g. stuttering, cluttering | |

| Disorders of articulation e.g. cleft palate, glossectomy | |

| Reception | Hearing impairment |

| Pesception/recognition | Agnosia |

| Language decoding | Language disorders Aphasia Developmental language disorders |

| Message decoding | Cognitive disorders Thought disorders Autism Learning difficulties |

Problems of this kind are grouped under the heading of psychopathology -the study of mental illness. This notion covers a wide range of disturbances, ranging from mild emotional problems to the severest forms of mental abnormality. It is a highly complex and controversial field, containing several competing systems of classification and terminologies in addition to conflicting theories of aetiology and modes of intervention. The effect of a psychopathology on communication is also variable. Some disorders, such as schizophrenia, autism and dementia, have profound communicative consequences; others, such as phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorders, have few communicative effects.

In the classification of mental illness, one of the most traditional distinctions is that drawn between neurosis and psychosis. Under the heading of neurosis is included a broad range of moods, fears, preoccupations and exaggerated traits about which a person is to some degree defensive or anxious. For example, a person may have an irrational fear of heights, or spiders, the fear being out of all proportion to the stimulus (what is known as a phobia). They may have an exaggerated concern over their health or bodily functions (hypochondria), or find that they act in obsessive or compulsive ways (as in compulsive washing, stealing, fire-lighting). Anxiety disorders are also included under the heading of neurosis, together with hysterical or conversion reactions, where aspects of a person’s physiology fail to work normally, although there is nothing wrong organically. For example, stress might lead to sexual impotency, poor vision, or (compare p. 199) loss of voice. All these neuroses have two things in common: patients cannot readily control their reactions through their own efforts; and they are only minimally out of contact with reality – they generally recognize the inappropriateness of their feelings and behaviour, and will often seek advice and help, especially from psychotherapy.

In this respect, neurotic reactions are said to differ from the second main category of mental illness: psychotic reactions or psychoses. These are major psychiatric disturbances, which often have serious communicative consequences. They differ from neuroses in that there is a fundamental disintegration of personality, with patients no longer being aware of the abnormal nature of their condition, and accepting their behaviour as a normal way of living. A distinction is generally made between organic and functional types. Organic psychoses, as the name suggests, are disorders where there is a demonstrable physical abnormality in the brain. Examples include the abnormal brain degeneration that may accompany ageing, known as senile dementia: the most common form is Alzheimer’s disease. In Alzheimer’s disease there is a loss of neurons throughout the brain, with regions of the pre-frontal and temporal cortex and the limbic system (areas important for planning, abstract thought, language and memory) particularly subject to cell loss. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease have progressively little or no insight into their problems, and make no effect to care for themselves. Sufferers experience a broad spectrum of cognitive deficits and gradually become detached from reality and disoriented as to who they are, and where they are. The linguistic impairments begin with difficulties in word-finding (or lexical retrieval) and changes at the level of discourse structure and pragmatics. The speaker may repeat the same topics again and again and have difficulty making contributions to the conversation when a new topic is introduced by another speaker. As the condition progresses, the vocabulary and pragmatic difficulties become more marked, and all levels of language processing become impaired, both in comprehension and production. In the late stages, the sufferer may have little understanding of spoken or written language and may be mute, with output restricted to repetition of others’ utterances (a behaviour called echolalia) or a small stock of stereotyped phrases and sentences (perseverations).

Functional psychoses, by contrast, are disorders where no underlying physical abnormality can be established (which is not, of course, to say that this does not exist – merely that none has been found, using present day techniques (p. 147)). This is in fact currently a controversial issue in the main category of functional psychosis, schizophrenia. It is possible that excessive levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine may be responsible for the symptoms observed, in which case we should be dealing with an organic disturbance. Dopamine affects regions of the brain important in mediating emotion, thought and personality; these include the amygdala, and the temporal and frontal lobes. Evidence of genetic factors in the disorder also point to an organic cause; but the point is disputed, and some argue that the neurochemical and structural abnormalities in the brains of schizophrenic patients are due to the effects of antipsychotic medication. The chief symptoms of the disorder are major abnormalities and fluctuations in mood, unexpected (inappropriate, dramatic) reactions to normal situations, social withdrawal, delusions and hallucinations. The communicative signs are most marked at a pragmatic level. During psychotic episodes, the patient may be unwilling to communicate, or output may be chaotic with constant shifts in topic, incoherence between sentences, perseverations and inappropriate emotional expression (e.g. in intonation and tone of voice). Comprehension may also be disrupted, for instance an innocuous utterance might be interpreted as a threat. Several of these features can be seen in the following sample, taken from a conversation with a female schizophrenic, in her mid-50s, with a long history of anxiety problems and institutionalization.5

| T | you’re in ‘ward thirtèen now/ |

| P | yès/ |

| yès/ | |

| was – | |

| been – | |

| I’ve been | |

| I’m – in – in | |

| I’m in ‘ward thirtèen/. | |

| T | how ‘long have you been in ‘ward thirtèen/ |

| P | gòod ‘while/ |

| a ‘few ‘years I thínk/ | |

| ‘two or three ‘years I thínk/ | |

| I’m not – | |

| yès/ | |

| T | do you líke it on ‘there/ |

| P | not bád/ – ùsual/ |

| T | have you ‘got any frìends ‘Mary/ |

| P | from the sỳna – er – |

| ‘Anytown sỳnagogue/. | |

| ‘please Gòd/. | |

| I’ll be gòing on the ‘ninth of Jánuary/ | |

| T | you’ve got frìends ‘there hàve you/ |

| P | yès/. |

| yès/. | |

| fróm/ – | |

| ‘used to be with me ín/ – | |

| gòod while ‘back/ | |

| er –’May in – | |

| ‘used to be ‘with me gòod while ‘back’ | |

| T | tèll me Máry/, ‘what ‘things do you ‘like dòing/ |

| P | I ‘used to be ‘in the ‘laun – |

| I was. | |

| I don’t knòw/ | |

| they ‘carried òn a bit/. | |

| but I ‘don’t knòw/ | |

| I mìght be going báck/–– | |

| ‘Monday the sècond/. | |

| I ‘don’t knòw/ | |

| it’ll be ‘bank holiday here/. | |

| I ‘don’t knòw/ | |

| the fòllowing week/ – | |

| Sùnday/ – | |

| ‘Monday ‘week I thínk/ |

This patient would tend not to speak at all, unless directly questioned. Most of her sentences are short; many are unfinished; and there is much disjointedness between one sentence and the next. Her tendency to split up a meaning into smaller chunks, giving each a separate intonation unit, is clearly illustrated by the transcription, where the units are put on new lines. Her tendency to repeat, or partly repeat, what she has said is also noticeable. What does not appear in the transcript is an indication of her general behaviour throughout the conversation – in particular, the way in which she avoided eye contact, and generally left the therapist with no sense of ‘rapport’.

A pre-linguistic pathology for which there is a clear organic basis is the cognitive disorder that follows damage to the pre-frontal cortex, as illustrated by the case of Phineas Gage (p. 105). This brain region is responsible for executive functions, and by extension, disorders of this type are sometimes called ‘dysexecutive’ or ‘frontal lobe’ syndromes. These disorders can occur following head injuries caused by road traffic accidents, blows and falls. The pattern of brain injury is generally diffuse, with delicate brain tissues being subject to impact and rotational forces which cause crushing of tissue against the skull and twisting and tearing of axons and blood vessels. The pre-frontal cortex is particularly vulnerable to injury because of its juxtaposition to a shelf of bone which separates the cranial cavity from the nose and eye cavities. The communicative component of frontal lobe syndrome is again distinguished by difficulties at the level of pragmatic and discourse structure – a recurring pattern of deficit in the pre-linguistic pathologies.

In addition to acquired disorders, there are a series of developmental conditions which operate at the pre-linguistic stage of the communication chain. Mental handicap (or learning difficulty) is a major category of psychopathological disorder which is of particular concern to the language pathologist. Individuals who fall within this category are likely to have cognitive, emotional or social skills which place them significantly below the level of the rest of their age group. A range of disorders are associated with the condition, including the genetic abnormality of Down’s syndrome, metabolic disturbances such as phenylketonuria (a disorder in which the child is born without the enzymes necessary to metabolize certain proteins, leading to a build up of toxic substances within the brain), and disabilities caused by infections such as meningitis or serious brain trauma, including birth anoxia in early life.

It is impossible to generalize about either the cognitive abilities or language skills in the context of learning disability. There is no straightforward correlation between any of the many syndromes and the language produced. Children with Down’s syndrome, for example (compare p. 27), will show a wide range of individual differences in their cognitive profiles and linguistic abilities. Perhaps the only safe claim that can be made is that when learning disabilities become really severe, there will be no language – which is hardly a brilliant insight. And yet, even here there is great scope for research. Even in the minimally purposive behaviour of the most severely handicapped, there may be signs of pattern, or desire to communicate, which might be made the basis of a teaching programme. What, upon first encounter, might seem to be random grunts may on analysis turn out to be a systematic use of a very limited vocal apparatus. Everything depends, it would seem, on the investigator and teacher finding the right mode of input to the child, and to keep trying, if early attempts to make contact fail. It is an easy, and a natural, reaction to give up with such children, and conclude that ‘they just won’t learn’. Such comments, properly interpreted, can only mean: ‘so far, I have not been able to find a way to enable them to learn’. Whether it is practical or economical to keep trying, of course, given the pressing demands of others for attention, is a difficult and often emotional decision. But theoretically, at least, the answer is plain: of course one keeps trying. And from the analytical point of view what this means, usually, is careful analysis – not only of the children’s language (if any) but of the language of their environment, from which they are attempting to learn. How carefully has this been structured, to enable them to make best sense of it? One of the general problems with mentally handicapped children or adults is the difficulties they have in resolving a large number of competing stimuli. They cannot cope with too many inputs at once, but get confused. Using this guideline, then, we can look at the language inputs to children, to see whether they are too complex for them. It is very easy for complexity to creep in, unnoticed. One child’s small teddy was being referred to as ‘teddy’, ‘cuddly’, ‘Fred’ and other names, by the people who came into contact with him; no-one had bothered to check whether they were all using the same language to the child, and as a result they unwittingly complicated his world in this small but crucial respect. Standardizing the learning environment, and yet not making it so stereotyped that there is no potential for growth and creativity: this is one of the main methodological issues facing those who work in learning disability.

Autism is a further developmental psychopathology which has profound consequences for communicative ability. It is usually identified in the second or third year of life and is a disorder for which, at present, no definite organic cause has been identified, although there is much debate about possible neuropathological mechanisms behind the disorder. Autism represents a complex pattern of abnormal behaviour in which three core behavioural deficits are identified: bizarre interpersonal relationships (such as avoidance of eye contact, lack of response to others, no attempt to initiate contacts, preference for objects rather than people), obsessive and ritualistic behaviour, and communication difficulties. The following extract illustrates the tendency of the autistic child not to respond directly to conversational stimuli, but to keep up a monologue of his own:

| T: | ‘what are you going to ‘do with ‘that car nòw/ |

| P | I like my cár (pushing it on floor) |

| T | lòok/. I’ve got ‘one like thát/ |

| P | in hère it ‘goes (pushing car into garage) |

| T | ‘don’t for’get to ‘shut the dóors/ |

| P | ‘find the màn nów/ (looking about)… |

In each case the child ignored, or seemed to ignore, the therapist’s stimulus sentence, and yet by keeping up a flow of language an ‘apparent’ conversation was obtained.

In the discussion of the holistic approach (p. 18), it was suggested that it is important to consider an individual’s communicative impairments in the context of the total cognitive profile. This is particularly true in cases of pre-linguistic pathology, where much of the communicative impairment follows directly from cognitive impairments. The management of pre-linguistic pathologies, in particular, requires full consideration of a range of cognitive functions, and language pathologists working with these conditions often work in tandem with psychologists. The word-retrieval difficulties of the person with Alzheimer’s disease need to be viewed against the backdrop of general difficulties with storage and retrieval of information from memory. The failure of a child with autism to show usual patterns of eye contact in an interaction has to be evaluated against more general impairments in social relationships. The communicative impairments of individuals with pre-linguistic pathologies are often some of the most evident signs of the disability. The chaotic thought of the schizophrenic patient is not available to observation, but the incoherent encoding of these same thoughts into language is clearly apparent. Communication, by its essential nature, is a very public function and, rather like an iceberg, it is possible to see the communicative manifestations which appear at the surface, but to neglect the underlying mass of other cognitive abilities which underpin and interlink with language. The proper management of the pre-linguistic conditions must necessarily adopt a broad perspective on behaviour.

Language Disorders

The essential characteristic of the previous category of communicative disability – the pre-linguistic or cognitive disorders – is that they represent a very broad deficit a:ross a range of cognitive and other abilities. In the second broad category of communicative deficits – language disorders – we are dealing with disabilities which feature more specific impairment of language, and these disabilities are often referred to as specific language disorders. This is not to say, however, that they are purely linguistic impairments. It may be that they are underpinned by a cognitive deficit, but one which has much more discrete consequences than the cognitive failures of dementia, schizophrenia and the like. It is also important not to lose sight of the fact that a language disorder may have effects on other cognitive functions, such as memory or concept development. Whereas the model of the communication chain represents pre-linguistic and linguistic deficits as discrete entities, in reality we are dealing with closely interrelated functions.

The distinction between specific language disorders and more global cognitive disorders is important in the diagnosis and management of conditions. Whereas teaching specific vocabulary items or grammatical structures might be an important component in the treatment of specific language difficulties, communicative impairments linked to more general cognitive deficits might first benefit from intervention directed at underlying cognitive deficits. For this reason, the initial evaluation of an individual, particularly a child, with a language disorder may consider a range of abilities in both a linguistic and a non-linguistic sphere. Psychological assessments such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children are divided into verbal (language) and performance scales.6 Assessment of a child with a specific language disorder may result in unequal scores across verbal and performance scales, with a performance score which may be within the normal range expected for a child of that chronological age, but a verbal score significantly below the expected range. A child with a language disorder which is a component of a more general developmental delay might show a more balanced profile of verbal and performance scores, although both scores would be significantly below those expected for a child of a particular chronological age.

An important characteristic of language disorders is that their effects may appear at different points in the communication chain, and in any of the modalities of language use. The disorder may affect both language encoding and decoding – that is, the patient could have difficulties both in formulating linguistic messages and in understanding them. It is possible, however, that language encoding alone may be affected, with the ability to understand language being relatively normal; and, more rarely, that language decoding may be affected, with the ability to produce language appearing normal. In both cases, there needs to be careful assessment by the language pathologist, because comprehension disorders may go unnoticed – the patient perhaps using other sources of information to decode messages, such as the contextual or the non-verbal (see p. 82). In addition to affecting performance across input and output, language disorders may disrupt performances across both auditory and visual channels of language use – that is, speech/listening and reading/writing. Thus a child with a language disorder may have difficulties in creating grammatical sentences in speech, and problems of a similar order may also be observed in writing. Pre-school children with language disorders may also go on to have difficulties in learning to read and write.

Different degrees of involvement of the four channels of language use result in one patient potentially being very different from another. Language disorder is not a homogenous category. Not only are there differences in performance across modalities; patients may also differ in the type of difficulty they have within modalities, such as when formulating a spoken message. One patient may have particular difficulty in producing a grammatical sentence, whereas another may have problems in finding the appropriate words for use in a sentence. The language pathologist might describe the first patient’s difficulty as one of grammatical encoding, and the second as one of semantic or lexical encoding. Any of the levels of language organization that were identified in Chapter 2 – grammar, semantics, phonology and pragmatics – may be affected, and to varying degrees. The language pathologist must therefore have considerable skill in performing linguistic analyses in order to be able to pinpoint areas of deficit in the patient’s linguistic knowledge and performance. During the 1970s, several important developments in the analytical study of language disability took place within the range of disciplines categorized as ‘behavioural’ (p. 30). The application of ideas from the fields of psychology and linguistics have, as a result, shaped present-day perceptions of language disability.

From this account, it will be clear that the proper explanation of a patient’s linguistic symptoms is a complex and time-consuming process. A language sample has to be analysed into its various levels of organization, the interactions determined, and the rules governing the competence of the impaired speaker deduced. To engage in clinical linguistic diagnosis is a truly professional task, and to be successful it requires a degree of training, time, resources, status and pay for its practitioners which one would associate with any complex area of enquiry. Unfortunately, as language clinicians and teachers know only too well, it is rare to find all these elements being satisfactorily recognized, and thus it is routine to encounter teaching and therapy taking place where it has been possible to engage in only a minimum of analysis. It is not surprising, then, to hear complaints from professionals that they do not have the time to practise the techniques associated with the behavioural model of investigation, apart from a few special settings, such as residential speech and language schools or university language pathology clinics.

The solution to this problem goes well beyond the brief of the present book, involving a wide range of political and professional issues. But it is important to stress that no solution will be found if it ignores the clinical realities of the nature of language disability. Given the demonstrable enormous complexity of human language, it should be no surprise to discover that language disabilities are also complex, and require correspondingly complex intervention procedures. A full clinical linguistic enquiry is thus a major enterprise, involving the description and analysis of the patient’s language at several points in time, and also of the kind of language being used to the patient by the people who have a caring role. The complexity is no greater, in principle, that that which is encountered in medical diagnosis. In practice, however, the two domains are worlds apart. If behavioural studies of language disability had the range of resources corresponding to the hospital pathological laboratory and the medical hierarchy (from general practitioner to hospital consultant), the situation would be drastically different.7

Let us now move to the more specific discussion of language disorders. They may occur in two broad forms: acquired and developmental. The chief acquired language disorder, aphasia, results from damage to the central nervous system and, in particular, the cerebrum. Previously established language knowledge is lost or disturbed by the brain injury. Conversely, a developmental language disorder represents acquisition of language knowledge at an abnormally slow rate, with the consequence that children are significantly different from their peers in language performance.

Aphasia

Aphasia (sometimes also called dysphasia) is an acquired language disorder.8 Established language knowledge is disrupted by damage to (usually) the left hemisphere of the cerebrum. Damage to the temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes can especially disturb language functions. Controversies abound within the field of aphasiology – terminological, theoretical, and methodological. We may begin with an uncertainty of definition. Is aphasia a specific language disorder – does it affect language and only language – or does it represent an impairment of language together with broader cognitive or intellectual deficits? According to the British neurologist, Henry Head, for example, aphasia was a disorder of ‘symbolic formulation and expression’.9 Language, being the main means of symbolic expression, would be centrally affected; but so would other forms of behaviour involving symbols, e.g. the ability to understand traffic signs, play cards, interpret gestures, produce drawings. There would also be changes in the intellectual capacities of the person with aphasia, such as an inability to retrieve and store information in memory, draw logical conclusions, perform arithmetical operations or pay attention. There would be a general reduction in efficiency of information processing, e.g. the aphasic person would respond more slowly, and tire more quickly. An individual might show personality changes, perhaps becoming more irritable, emotional or depressive. Given these characteristics, seen in many patients, it was difficult to see aphasia as constituting a purely linguistic disorder. At the very least, it seemed to involve a more deep-rooted incapacity to use symbols (asymbolia), and cognitive and personality changes as well.

A more specific conception of aphasia defines it solely as a linguistic pathology. Advocates of such a view might point to evidence of people with aphasia who manage to live independently, coping with activities of daily living without help, and who are able to manage their finances and drive a car. These individuals appear to have clear communicative intentions which they struggle to realize either through language, or via gesture, drawing or attempting to cue in the listener to the intended message. Individuals with aphasia may show changes in personality such as depression or anxiety, but these changes may be a reaction to the frustration of communicative difficulties and the changes in social roles that result from a stroke or other brain injury. On this account, therefore, we are exclusively within the area of language, and we will allow for the possibility that aphasic people will be very much the same as they were before – in all respects – bar their reduced ability in speaking, comprehending, reading or writing.

In the final analysis, the difference between the two approaches may rest on how one interprets the association of deficits following brain damage. An individual patient may show a variety of impaired abilities following brain injury, and this may be because the lesion may have damaged a variety of neuronal groups which are involved in different functions. The larger the amount of brain tissue that is damaged, the greater the likelihood that the patient will experience impairments across a wide range of functions. Conversely, a patient with a small lesion, perhaps centred in the auditory processing areas of the temporal cortex, may have difficulties restricted to the domain of language and would show few signs of intellectual or personality changes in domains largely independent of language. Many of the differences between the several theoretical positions taken concerning aphasia are the result of sampling and methodological differences on the part of the analysts. It is wise, accordingly, for the clinician to adopt a fairly flexible position at the outset – expecting linguistic problems to be the primary symptoms, but not excluding the possibilities of significant deficiencies in other areas of cognition.

The main impression that hits anyone entering the field of aphasiology for the first time is the bewildering variety of pathological behaviours that are presented by people who have suffered from brain damage. No two patients seem identical, as far as their linguistic and cognitive faculties are concerned. And this turns out to be more than just a first impression because detailed analysis of patient samples show the differences to be considerable. This leads to a second major controversy within aphasiology – whether similarities in behaviour between some aphasic people permit the disorder to be divided into subtypes or different syndromes, or whether individual differences in behaviour should be emphasized, with any subtypes that might be identified being regarded as abstract categories which cannot account for the behaviour of the individual aphasic. In practice, a number of classificatory schemes are often used to categorize patients for research purposes and to assist communication between clinicians. Most of these schemes stem from a binary classificatory system, some of the pairs of terms being as follows:10

| fluent | non-fluent |

| receptive | expressive |

| sensory | motor |

| Wernicke’s | Broca’s |

| posterior | anterior |

The terms in each column are often used synonymously, and the differences in terminology stem from the different disciplines from which researchers into aphasia are drawn. Labels such as motor/sensory, anterior/posterior, and Broca’s/Wernicke’s are based upon distinctions in neurology. Lesions anterior to the central sulcus, in the region of the motor cortex and Broca’s area, are believed to result in forms of aphasia which are distinctively different from those caused by lesions posterior to this boundary. The fluent/non-fluent and receptive/expressive dichotomies are based to a greater extent on description of the most evident impairments displayed by the aphasic patient, such as hesitant and laboured speech output in non-fluent aphasia. We have already said that individuals with aphasia present with a bewildering variety of pathological behaviour. The reduction of this diversity to a binary classificatory scheme inevitably entails that there will be considerable variety within each category and such schemes can be seen only as a preliminary way of subdividing the spectrum of aphasic impairments.

How can we characterize a non-fluent or expressive aphasic patient? Here is one sample, taken from a man aged 51, who two years previously had suffered a left-hemisphere CVA (see p. 114). The therapist (T) and the patient (P) are discussing the activities the patient undertakes at a day centre that he attends.11

| T | ‘they do all sorts of áctivities/. wòodwork * and |

| P | * nò/ ‘me còok/ |

| T | you cóok/ grèat/ |

| P | àye/ . once a wèek/ |

| T | yěah/ . ‘that’s todày/ Thùrsday/ |

| P | àye/ . and thèn/ – ‘night-tìme/ sèven o”clock swímming/ |

| T | rêally/ |

| P | yès/ . smàshing/ |

| T | ‘how do you ‘manage one hànded/ |

| P | oh it’s alrìght/ àye/. màte/. ‘mate . ‘Jack ‘comes and àll/ but – er/. oh dèar/. ‘Jack – er . òld/ er • sèventy/. ‘no . sìxty ‘eight/. Jàck/- but swîm/. ‘me . ‘me ‘like thìs/ – swìmming – er/ – ‘I ‘can’t sày it/ – but Jâck/ – er – ‘swimming on frònt/, er – bàck/ |

| T | so he cán * do – |

| P | * àye/ but ‘one hànd |

| T | ‘one-’handed ‘back-stròke/. I ‘can’t i’magine what it’s lìke . ‘swimming one-hànded/. ‘doesn’t one side keep sìnking/ |

| P | àye/ . it’s àlright though/ |

The first characteristic of the extract we would note is that the two interactants are working together to construct this dialogue. Unlike the example transcripts given for the pre-linguistic pathologies of schizophrenia (p. 158) and autism (p. 161), there is no evidence of pragmatic disability or interactional failure. The patient responds promptly to the therapist’s questions and provides relevant information in his answers, which in turn suggests that the patient’s comprehension is not grossly impaired. But there are abnormalities in the patient’s language output. Aphasiologists often make preliminary observations about a patient’s language under two headings: grammatical or sentence processing, and lexical-semantic processing. Observations of grammar would include the patient’s ability to understand and produce elements of clause and phrase structure (p. 45). Lexical-semantic observations would concern vocabulary choice: is the patient able to select words which convey the intended meaning, and is the patient able to locate word forms with ease? The extract illustrates features of both grammatical and lexical-semantic disturbance, with the disruptions of the former being most marked. Under the heading of grammar, we would note the reduced and incomplete sentence structure (what is often referred to as agrammatic speech). The intonation units are also short, and pausing is frequent – features which are particularly important in the categorization of the extract as an instance of non-fluent aphasic speech. There is one sentence within the aphasic person’s output that is a complete sentence (I can’t say it). This sentence is atypical of the rest of the data, both for its completeness and also for the correct use of the first person pronoun. Notice that in all other instances in the extract I is replaced by me – an unusual feature of adult language although one which is characteristic of early child language. This suggests that the sentence is a stereotype: a linguistic unit which has been stored as a complete chunk and is used at specific points in the interaction, namely when the patient has difficulties in formulating his message. In terms of maintaining the interaction, the stereotype is useful as it signals to the other participant that the next part of the message may contain an error, or that help or patience may be needed from the non-aphasic participant in order to convey this part of the message. Under the heading of lexical semantics, there are two instances of mis-selection of vocabulary in the extract (seventy/sixty-eight; front/back), but in each instance the patient rapidly self-corrects his errors, which suggests that the degree of lexical-semantic impairment is mild. The mis-selected words are semantically linked to the intended target, and this error type is labelled semantic paraphasia.12

The second extract is taken from a conversation with a man with a diagnosis of fluent aphasia. The patient is aged 67, and experienced a left-hemisphere CVA three months earlier. The therapist and patient are discussing the patient’s war-time military service.

| T | so you were at Dùnkirk/ |

| P | yès/ |

| T | ‘what do you re’member of thàt/ |

| P | [nə nə] not very ‘far because they ‘kicked us oùt/ |

| T | do/ did you have to get a ‘boat from the bèach/ |

| P | yès/ but ‘then we had to ‘come bàck because they were/ – [sə psə psə psə] (+ gesture) they were ‘sending ‘things dòwn/you knòw/so we ‘came bàck/. we ‘came bàck/ and we ‘came up from –/ rĭght up/ then we ‘got òut/ – ònce/ – er er a gùn/ er nò/. ‘what do they cáll ‘them/ the vèry ‘little/ – the smàll men/, the smàll – |

| T | the smàll ‘men/ |

| P | nò/ ‘small sòldiers/. nò/ the òther ‘one/. say . ‘not sòldier/. ‘not sòldier – / |

| T | are they the Gúrkhas/ |

| P | nò/. nò/. ‘what’s the ‘opposite to a sóldier/ |

| T | sàilor/ |

| P | thàt’s it/ |

The degree of collaboration between the participants is a remarkable feature of this transcript. The patient has marked word-finding or lexical retrieval difficulties in the latter part of the extract. In order to circumvent this linguistic difficulty, the patient cues the therapist to the intended word through asking her questions and giving feedback on the accuracy of her guesses at the intended target. The accuracy with which the patient monitors the therapist’s guesses suggests that his comprehension abilities are relatively unimpaired. There is considerable pausing within the patient’s turns, but interspersed between these there were also complete and often lengthy intonational units. It is this latter characteristic that leads to the categorization of the speaker as a fluent aphasic. In terms of grammatical structure, many sentences are incomplete but there are also examples of full sentences. The incomplete sentences may be a product of the marked lexical-semantic disruption evident in the extract. The patient tries to talk around a subject (circumlocution), for example, sending things down for ‘bombing’; specific items of vocabulary are replaced by general words, such as things for ‘bombs’, and small men for ‘sailors’.

Let us turn now to another example of a fluent aphasia, but in this instance where the patient also shows comprehension or receptive problems. The following sample is taken from a 66-year-old male patient, six months after a left CVA, with associated right hemiplegia. He spoke rapidly and loudly, producing several stretches of fluent but unintelligible speech (jargon, indicated below by the number of syllables), and paying little attention to many of the therapist’s efforts to intervene. There were also major problems in his reading and writing. In this extract, the therapist is trying to establish whether the patient can identify various objects in the room. The sample shows some echolalia – repetition with minimal change of what has just been said to him, in a context which suggests that comprehension is absent. There is also some perseveration on words – a tendency to repeat a behaviour, in this instance a word, even though it is no longer appropriate to continue.

| T | ‘show me a pìcture/ on the wàll/ |

| P | ‘picture on the wàll/ òh by [2 syllables]/ thère/ [looks in wrong direction] in the . [2 syllables] look at the er . whàt do they cáll them/ ‘knights . of the chùrch/and there [1 syllable] we can ‘go no [syllable] and . of. over [syllable] . and [2 syllables] . there’s pàrt of [2 syllables] |

| T | yès/ ‘show me the pìcture/ of the mòuse/ |

| P | the móuse/ |

| T | ‘where’s the pìcture/ of the mòuse/ |

| P | òh/ ‘picture of a môuse’. pìcture/ . mòuse/ |

| T | it’s ‘up on the wàll/ it’s next to the càlendar/. sée/. hère/ |

| P | thére/. ‘this one hère/ |

| T | thàt one/ |

| P | oh/. you’ve’got to’move . |

| T | the ‘calendar is ‘next to that/ . |

| P | thàt’s right/ . it’s ‘next to the ‘person . |

| T | ÒK/ |

| P | ‘that where . and ‘there . and ‘there something here as wèll/somewhere ‘other’end of. [4 syllables] ‘there’s…. |

In this sequence, the lack of comprehension is very much in evidence: the patient echoes the therapist’s sentences, but does not relate them to the objects in question; several of his own sentences are unrelated to the theme being discussed; several are relatively ‘empty’ of meaning (e.g. what do they call them; this one here); several grammatical structures are begun, but they lead nowhere, and it is unclear what, if any, meaning they have for the patient. Overall, there is a confident, definite intonation, which in fact is no guide to the patient’s ability.

There are certain important issues in the aphasia literature which the above samples do not illustrate. The first concerns the extent to which all modalities of communication have been affected by the brain damage. The above discussion focuses on speech and listening comprehension; but what about reading and writing? Inability to read (alexia) and write (agraphia), along with their less severe forms (dyslexia and dysgraphia – though these terms are sometimes used to include the former, regardless of severity) may also be apparent, but in some patients reading and writing remain largely unaffected. It is also possible to have the one without the other (i.e. ‘pure alexia’, or ‘alexia without agraphia’), or to have the disorder focused solely on reading/writing ability, speech/auditory comprehension being largely unaffected. Because of the several possibilities for disturbance, full assessments of aphasia always include, as part of their battery of tests, components in which all four modalities of language are investigated. The possibility of independent impairment of the different modalities of language use indicates that the mental processing routes for the different input and output channels of language use – and presumably also their neurological substrate – are distinct. Where dissociations between performances across different modalities occur, brain damage has disrupted one processing route, but selectively spared others.

A second big issue concerns the extent to which the notion of aphasia can be applied to children as well as to adults. This is not a major issue if a stroke or other brain damage affects young children after they have acquired language: as with the adult, an aphasic condition can result.13 But the term has also been used to apply to children who, for some reason, have failed to develop language at all, or who have done so only partially or deviantly. The term developmental aphasia/dysphasia (occasionally childhood or infantile aphasia/dysphasia) is sometimes used in such cases, where the ‘obvious’ causes of underdeveloped language can be ruled out (i.e. there is no evidence of deafness, other learning disabilities, motor disability, or severe emotional or personality problems). This is a kind of diagnosis by exclusion: in the absence of known alternatives, one concludes that there must be some minimal brain damage present, and it is this which justifies the extension of the term. Against this, it has been argued that, if aphasia means basically ‘loss of acquired language’, then it is hardly right to use this label to apply to children who are slow to acquire language knowledge. Such children present very different problems of assessment and treatment, particularly with regard to the discussion of the issue of intermittent access to language knowledge in cases of acquired aphasia (p. 150). Whereas patients with acquired aphasia may show considerable variability in language performances, these same degrees of variation in behaviour are not observed in developmental conditions.

It should be plain, both from the terminological confusion which exists within this subject, and also from the uncertainty with which different aphasic syndromes are postulated, that this is an area of language pathology which provides enormous scope for research -perhaps more than any other. The importance of aphasia research is undenied – not only for clinical reasons (i.e. to help sufferers from the disorder) but also for theoretical reasons (to obtain a clearer understanding of the structure and function of the brain). Aphasia research has in fact been one of the main means of discovery about how the human mind processes language (compare p. 101). This is the only syndrome where the various levels of language (grammar, vocabulary etc.) can be seen functioning separately from each other. By examining what can go wrong, and whereabouts in the language system that something goes wrong, suggestions can be made about ‘how language works’, which might be useful in other contexts than the clinical. Aphasia, it has been said (though not without controversy), is a key to our understanding of language as a whole.14

Developmental language disorders

Most of the children who are noticeably behind their chronological peers in their ability to produce or comprehend speech fall into one of two categories: they are learning disabled (or mentally handicapped), to some degree; or they suffer from a degree of hearing loss. A significant number of children, however, manifest neither of these problems, and yet are still well behind their peers in language ability. These are the children who have been referred to in the past as developmentally aphasic, but in more recent usage, as having specific language disorder. Their diagnosis is classically one of exclusion (compare p. 24): there is no deafness or other sensory-perceptual deficit, no motor disorder, no evidence of global learning difficulties, and no psychiatric difficulty (such as maladjustment, or severe emotional problems). Their learning environments appear adequate, and parenting practices are not in any way unusual. On the other hand, they do display psychological, social and educational problems -although whether these are the cause or the result of the linguistic difficulty remains an imponderable. There is no gross neurological impairment, although advances in methods of brain imaging (p. 102) have shown indications of subtle abnormalities in brain structure.15

In recent years a great deal of progress has been made in our understanding of the bases of these disorders, through a range of psychological and linguistic studies which have investigated the problem from several interrelated points of view. Two broad hypotheses have been advanced: first, that the disorders are a consequence of a more fundamental deficit of a cognitive nature; second, that the disorders are a result of a deficit in the linguistic processing system alone. There is evidence to suggest that both hypotheses are right, some of the time. There is clear evidence that some of these children have deficits in their auditory perception ability (compare p. 143); some have problems in their auditory storage capacity (a very poor auditory short-term memory); some have difficulty in processing the information perceived through the auditory channel (requiring slowly presented inputs); and some have difficulty in attending to sequences of items presented auditorily (a ‘reduced auditory attention span’). An interesting feature is that the rhythmical abilities of many of these children are poor, both in non-verbal as well as prosodic ways (e.g. in dancing, movement, or tapping rhythms out). Some have poor awareness of symbolic behaviour generally, showing poor appreciation of what is involved in play, or gesture (particularly the case with children displaying autistic tendencies, compare p. 161). Some are highly distractible and disorganized in all aspects of their behaviour (hyperkinetic or hyperactive children). All of this adds up to a view that many of these children have definite cognitive problems, especially in relation to auditory imperception and attention control. If they do have these problems, then naturally their speech processing abilities will be affected. The disorder is not primarily one of language, on this view; and treatment would proceed primarily on the basis of attacking the underlying cognitive difficulty, e.g. by working on attention, space/time relationships, symbolic play or rhythmic skills.

By contrast, there are some children (as many as a third, according to some estimates) who display the same kind of marked language delay, but who seem to have few difficulties with any of the tasks referred to in the previous paragraph. On general sensory processing and auditory processing tasks, their performance is within normal limits, or only slightly abnormal. The analysis of their language brings to light a range of abnormal patterns which it is difficult to associate with any cognitive explanation, and we are forced to conclude that the problem is restricted to the linguistic processing system as such. These difficulties may be primarily phonological, i.e. the children have particular difficulty in learning the sound system of their language. Difficulties quite commonly lie in the development of the system of sound contrasts, resulting in speech which is not easily intelligible; and delay in acquiring the suprasegmental aspects of phonology (see p. 43) is possible, although less widely reported. Developmental disorders of grammar and semantics can also be identified. In the former, children might be significantly behind their peers in their morphological development or in their ability to combine linguistic units to form phrases, clauses and strings of sentences. In the latter, children might demonstrate a limited vocabulary, errors in word use, or particular difficulties in retrieving appropriate words. Difficulties in understanding may be present, as well as the more evident difficulties in speech. ‘Pure’ disorders – that is, disorders which can be observed in one level of language organization alone – are less common than disorders in which the child has difficulties across a range of levels of linguistic organization. In the pre-literate child, difficulties will be restricted to speech and the understanding of speech. But when the child subsequently is taught to read and write, problems of a similar order may be observed in written language.

Here is an example of a child who was diagnosed as having an expressive language problem. His comprehension of speech, using one of the standard tests, was normal for his age; hearing was within normal limits – indeed, everything that could be tested was within normal limits. The only trouble was that he was producing language such as the following, and he was 4 years of age:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree