Table 4.1)

Chest pain

The mention of chest pain by a patient tends to provoke more urgent attention than other symptoms. The surprised patient may find himself whisked into an emergency ward with the rapid appearance of worried-looking doctors. This is because ischaemic heart disease, which may be a life-threatening condition, often presents in this manner (

TABLE 4.1 Cardiovascular history

| Major symptoms |

| Chest pain or heaviness |

| Dyspnoea: exertional (note degree of exercise necessary), orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea |

| Ankle swelling |

| Palpitations |

| Syncope |

| Intermittent claudication |

| Fatigue |

| Past history |

| History of ischaemic heart disease: myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting |

| Rheumatic fever, chorea, sexually transmitted disease, recent dental work, thyroid disease |

| Prior medical examination revealing heart disease (e.g. military, school, insurance) |

| Drugs |

| Social history |

| Tobacco and alcohol use |

| Occupation |

| Family history |

| Myocardial infarcts, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, mitral valve prolapse, Marfan’s syndrome |

| Coronary artery disease risk factors |

| Previous coronary disease |

| Smoking |

| Hypertension |

| Hyperlipidaemia |

| Family history of coronary artery disease |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Obesity and physical inactivity |

| Male sex and advanced age |

| Raised homocysteine levels |

| Functional status in established heart disease |

| Class I—disease present but no symptoms, or angina |

| Class II—angina or dyspnoea during ordinary activity |

| Class III—angina or dyspnoea during less than ordinary activity |

| Class IV—angina or dyspnoea at rest |

* Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCVS) classification.

† New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

TABLE 4.2 Causes (differential diagnosis) of chest pain and typical features

| Pain | Causes | Typical features |

| Cardiac pain | Myocardial ischaemia or infarction | Central, tight or heavy; may radiate to the jaw or left arm |

| Vascular pain | Aortic dissection | Very sudden onset, radiates to the back |

| Aortic aneurysm | ||

| Pleuropericardial pain | Pericarditis +/− myocarditis | Pleuritic pain, worse when patient lies down |

| Infective pleurisy | Pleuritic pain | |

| Pneumothorax | Sudden onset, sharp, associated with dyspnoea | |

| Pneumonia | Often pleuritic, associated with fever and dyspnoea | |

| Autoimmune disease | Pleuritic pain | |

| Mesothelioma | Severe and constant | |

| Metastatic tumour | Severe and constant, localised | |

| Chest wall pain | Persistent cough | Worse with movement, chest wall tender |

| Muscular strains | Worse with movement, chest wall tender | |

| Intercostal myositis | Sharp, localised, worse with movement | |

| Thoracic zoster | Severe, follows nerve root distribution, precedes rash | |

| Coxsackie B virus infection | Pleuritic pain | |

| Thoracic nerve compression or infiltration | Follows nerve root distribution | |

| Rib fracture | History of trauma, localised tenderness | |

| Rib tumour, primary or metastatic | Constant, severe, localised | |

| Tietze’s syndrome | Costal cartilage tender | |

| Gastrointestinal pain | Gastro-oesophageal reflux | Not related to exertion, may be worse when patient lies down—common |

| Diffuse oesophageal spasm | Associated with dysphagia | |

| Airway pain | Tracheitis | Pain in throat, breathing painful |

| Central bronchial carcinoma | ||

| Inhaled foreign body | ||

| Other causes | Panic attacks | Often preceded by anxiety, associated with breathlessness and hyperventilation |

| Mediastinal pain | Mediastinitis | |

| Sarcoid adenopathy, lymphoma |

To help determine the cause of chest pain, it is important to ascertain the duration, location, quality, and precipitating and aggravating factors (the four cardinal features), as well as means of relief and accompanying symptoms (the SOCRATES questions; see

The term angina

The pain or discomfort is usually central rather

Questions to ask the patient with suspected angina

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

than left-sided. The patient may dismiss his or her pain as non-cardiac because it is not felt over the heart on the left side. It may radiate to the jaw or to the arms, but very rarely travels below the umbilicus. The severity of the pain varies.

Angina characteristically occurs with exertion, with rapid relief once the patient rests or slows down. The amount of exertion necessary to produce the pain may be predictable to the patient. A change in the pattern of onset of previously stable angina must be taken very seriously.

These features constitute typical angina (

TABLE 4.3 Clinical classification of angina from the European Society of Cardiology

| Typical angina | Meets all 3 of the following characteristics: |

| Atypical angina | Meets 2 of the above characteristics |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | Meets 1 or none of the above characteristics |

The pain associated with an acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina) often comes on at rest, is usually more severe and lasts much longer. Acute coronary syndromes are usually caused by the rupture of a coronary artery plaque which leads to the formation of thrombus in the arterial lumen. Stable exertional angina is a result of a fixed coronary narrowing. Pain present for more than half an hour is more likely to be due to an acute coronary syndrome than to stable angina, but pain present continuously for many days is unlikely to be either. Associated symptoms of myocardial infarction include dyspnoea, sweating, anxiety, nausea and faintness.

Other causes of retrosternal pain are listed in

Chest wall pain is usually localised to a small area of the chest wall, is sharp and is associated with respiration or movement of the shoulders rather than with exertion. It may last only a few seconds or be present for prolonged periods. Disease of the cervical or upper thoracic spine may also cause pain associated with movement. This pain tends to radiate around from the back towards the front of the chest.

Pain due to a dissecting aneurysm of the aorta is usually very severe and may be described as tearing. This pain is usually greatest at the moment of onset and radiates to the back. These three features—quality, rapid onset and radiation—are very specific for aortic dissection. A proximal dissection causes anterior chest pain and involvement of the descending aorta causes interscapular pain. A history of hypertension or of a connective tissue disorder such as Marfan’s syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome puts the patient at increased risk of this condition.

Massive pulmonary embolism causes pain of very sudden onset which may be retrosternal and associated with collapse, dyspnoea and cyanosis

Table 4.4a Differential diagnosis of chest pain

| Favours angina | Favours pericarditis or pleurisy | Favours oesophageal pain |

| Tight or heavy | Sharp or stabbing | Burning |

| Onset predictable with exertion | Not exertional | Not exertional |

| Relieved by rest | Present at rest | Present at rest |

| Relieved rapidly by nitrates | Unaffected | Unaffected unless spasm |

| Not positional | Worse supine (pericarditis) | Onset may be when supine |

| Not affected by respiration | Worse with respiration | Unaffected by respiration |

| Pericardial or pleural rub |

(

Spontaneous pneumothorax may result in pain and severe dyspnoea (

Gastro-oesophageal reflux can quite commonly cause angina-like pain without heartburn. It is important to remember that these two relatively common conditions may co-exist. Oesophageal spasm may cause retrosternal chest pain or discomfort and can be quite difficult to distinguish from angina, but is rare. The pain may come on after eating or drinking hot or cold fluids, may be associated with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and may be relieved by nitrates.

Cholecystitis can cause chest pain and be confused with myocardial infarction. Right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness is usually present (

The cause of severe, usually unilateral, chest pain may not be apparent until the typical vesicular rash of herpes zoster appears in a thoracic nerve root distribution.

Dyspnoea

Shortness of breath may be due to cardiac disease. Dyspnoea (Greek dys ‘bad’, pnoia ‘breathing’) is often defined as an unexpected awareness of breathing. It occurs whenever the work of breathing is excessive, but the mechanism is uncertain. It is probably due to a sensation of increased force required of the respiratory muscles to produce a

Table 4.4b Differential diagnosis of chest pain

| Favours myocardial infarction (acute coronary syndrome) | Favours angina |

| Onset at rest | Onset with exertion |

| May be severe | Less severe |

| Sweating | No sweating |

| Anxiety (angor) | Mild or no anxiety |

| No relief with nitrates | Rapid relief with nitrates |

| Associated symptoms (nausea and vomiting) | Associated symptoms absent |

| Favours myocardial infarction | Favours aortic dissection |

| Central chest pain | Radiates to back |

| Subacute onset (minutes) | Instantaneous onset |

| May be severe | Very severe |

| Favours myocardial ischaemia | Favours chest wall pain |

| Exertional | Positional |

| Occurs with exertion | Often worse at rest |

| Brief episodes | Prolonged |

| Diffuse | Localised |

| No chest wall tenderness (only discriminates between infarction and chest wall pain) | Chest wall tenderness |

volume change in the lungs, because of a reduction in compliance of the lungs or increased resistance to air flow. Cardiac dyspnoea is typically chronic and occurs with exertion because of failure of the left ventricular output to rise with exercise; this in turn leads to an acute rise in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, raised pulmonary venous pressure, interstitial fluid leakage and thus reduced lung compliance. However, the dyspnoea of chronic cardiac failure does not correlate well with measurements of pulmonary artery pressures, and clearly the origin of the symptom of cardiac dyspnoea is complicated.

Orthopnoea (from the Greek ortho ‘straight’; see

TABLE 4.5 Causes of orthopnoea

| Cardiac failure |

| Uncommon causes |

| Massive ascites |

| Pregnancy |

| Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis |

| Large pleural effusion |

| Severe pneumonia |

Paroxysmal

Cardiac dyspnoea can be difficult to distinguish from that due to lung disease or other causes (

Dyspnoea is also a common symptom of anxiety. These patients often describe an inability to take a big enough breath to fill the lungs in a satisfying way. Their breathing may be deep and punctuated with sighs.

Ankle swelling

Some patients present with bilateral ankle swelling due to oedema from cardiac failure. Patients with the recent onset of oedema and who take a serious interest in their weight may have noticed a gain in weight of 3 kg or more. Ankle oedema of cardiac origin is usually symmetrical and worst in the evenings, with improvement during the night. It may be a symptom of biventricular failure or right ventricular failure secondary to a number of possible underlying aetiologies. As failure progresses, oedema ascends to involve the legs, thighs, genitalia and abdomen. There are usually other symptoms or signs of heart disease.

It is important to find out whether the patient is taking a vasodilating drug (e.g. a calcium channel blocker), which can cause peripheral oedema. There are other (more) common causes of ankle oedema than heart failure that also need to be considered (

Palpitations

This is not a very precise term. It is usually taken to mean an unexpected awareness of the heartbeat.

Questions box 4.2

Questions to ask the patient with palpitations

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

There may be the sensation of a missed beat followed by a particularly heavy beat; this can be due to an atrial or ventricular ectopic beat (which produces little cardiac output) followed by a compensating pause and then a normally conducted beat (which is more forceful than usual because there has been a longer diastolic filling period for the ventricle).

If the patient complains of a rapid heartbeat, it is important to find out whether the palpitations are of sudden or gradual onset and offset. Cardiac arrhythmias are usually instantaneous in onset and offset, whereas the onset and offset of sinus tachycardia is more gradual. A completely irregular rhythm is suggestive of atrial fibrillation, particularly if it is rapid.

It may be helpful to ask the patient to tap the rate and rhythm of the palpitations with his or her finger. Associated features including pain, dyspnoea or faintness must be inquired about. The awareness of rapid palpitations followed by syncope suggests ventricular tachycardia. These patients usually have a past history of significant heart disease. Any rapid rhythm may precipitate angina in a patient with ischaemic heart disease.

Table 4.6 Causes (differential diagnosis) of dyspnoea, palpitations and oedema

| Favours heart failure | Favours lung disease | |

| History of myocardial infarction | History of smoking | |

| Onset after some exertion (asthma) | ||

| No wheeze | Wheezing | |

| PND | PND absent | |

| Orthopnoea | Orthopnoea absent | |

| Abnormal apex beat | ||

| Third heart sound (S3) | ||

| Mitral regurgitant murmur | ||

| Overexpanded chest | ||

| Pursed-lips breathing | ||

| Early and mid-inspiratory crackles | Fine end-inspiratory crackles | |

| Cough only on lying down | Productive cough | |

| Palpitations differential diagnosis | Ankle oedema differential diagnosis | |

| Feature | Suggests | Favours heart failure |

| Heart misses and thumps | Ectopic beats | History of cardiac failure |

| Worse at rest | Ectopic beats | Other symptoms of heart failure |

| Very fast, regular | SVT (VT) | Jugular venous pressure elevated (+ve LR 9.0 |

| Instantaneous onset | SVT (VT) | Favours hypoproteinaemia |

| Offset with vagal manoeuvres | SVT | Jugular venous pressure normal |

| Fast and irregular | AF | Oedema pits and refills rapidly, 2–3s |

| Forceful and regular—not fast | Awareness of sinus rhythm (anxiety) | Favours deep venous thrombosis or cellulitis |

| Unilateral | ||

| Skin erythema | ||

| Calf tenderness | ||

| Severe dizziness or syncope | VT | |

| Pre-existing heart failure | VT | |

| Favours drug-induced oedema | ||

| Patient takes calcium channel blocker | ||

| Favours lymphoedema | ||

| Not worse at end of day | ||

| Not pitting when chronic | ||

| Favours lipoedema | ||

| Not pitting | ||

| Spares foot | ||

| Obese woman | ||

PND = paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

SVT = supraventricular tachycardia.

VT = ventricular tachycardia.

AF = atrial fibrillation.

* McGee S, Evidence-based clinical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

† Khan NA, Rahim SA, Avand SS et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA 2006 Feb 1; 295(5):536–546.

Table 4.7 Differential diagnosis of syncope and dizziness

| Favours vasovagal syncope (most common cause) |

| Onset in teens or 20s |

| Occurs in response to emotional distress, e.g. sight of blood |

| Associated with nausea and clamminess |

| Injury uncommon |

| Unconsciousness brief, no neurological signs on waking |

| Favours orthostatic hypotension |

| Onset when getting up quickly |

| Brief duration |

| Injury uncommon |

| More common when fasted or dehydrated |

| Known low systolic blood pressure |

| Use of antihypertensive medications |

| Favours ‘situational syncope’ |

| Occurs during micturition |

| Occurs with prolonged coughing |

| Favours syncope due to left ventricular outflow obstruction (AS, HCM) |

| Occurs during exertion |

| Favours cardiac arrhythmia |

| Family history of sudden death (Brugada or long QT syndrome) |

| Anti-arrhythmic medication (prolonged QT) |

| History of cardiac disease (ventricular arrhythmias) |

| History of rapid palpitations |

| No warning (heart block—Stokes-Adams attack) |

| Favours vertigo |

| No loss of consciousness |

| Worse when turning head |

| Head or room seems to spin |

| Favours seizure |

| Prodrome—aura |

| Tongue bitten |

| Jerking movements during episode |

| Sleepiness afterwards |

| Head turns during episode |

| Follows emotional stress |

| Cyanosis |

| Muscle pain afterwards |

| Favours metabolic cause of syncope (coma) |

| Hypoglycaemic agents, low blood sugar |

AS = aortic stenosis.

HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Patients may have learned manoeuvres that will return the rhythm to normal. Attacks of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) may be suddenly terminated by increasing vagal tone with the Valsalva manoeuvre (

Syncope, presyncope and dizziness

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness resulting from cerebral anoxia, usually due to inadequate blood flow. Presyncope is a transient sensation of weakness without loss of consciousness. (See

Syncope may represent a simple faint or be a symptom of cardiac or neurological disease. One must establish whether the patient actually loses consciousness and under what circumstances the syncope occurs—e.g. on standing for prolonged

Questions to ask the patient with suspected peripheral vascular disease

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

periods or standing up suddenly (postural syncope), while passing urine (micturition syncope), on coughing (tussive syncope), or with sudden emotional stress (vasovagal syncope). Find out whether there is any warning, such as dizziness or palpitations, and how long the episodes last. Recovery may be spontaneous or the patient may require attention from bystanders.

If the patient’s symptoms appear to be postural, inquire about the use of anti-hypertensive or anti-anginal drugs and other medications that may induce postural hypotension. If the episode is vasovagal, it may be precipitated by something unpleasant like the sight of blood, or occur in a crowded, hot room; patients often sigh and yawn and feel nauseated and sweaty before fainting and may have previously had similar episodes, especially during adolescence and young adulthood.

If syncope is due to an arrhythmia, there is a sudden loss of consciousness regardless of the patient’s posture; chest pain may also occur if the patient has ischaemic heart disease or aortic stenosis.

It is important to ask about a family history of sudden death. An increasing number of ion channelopathies are being identified as a cause of syncope and sudden death. These inherited conditions include the long QT syndrome and the Brugada syndrome. They are often diagnosed from typical ECG changes. In addition, certain drugs can cause the acquired long QT syndrome (

| Associated with QT interval prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias |

| Anti-arrhythmics; flecainide, quinidine, sotalol, procainamide, amiodarone |

| Gastric motility promoter; cisapride |

| Antibiotics; clarithromycin, erythromycin |

| Antipsychotics; chlorpromazine, haloperidol |

| Associated with bradycardia |

| Beta-blockers |

| Some calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem) |

| Digoxin |

| Associated with postural hypotension |

| Most antihypertensive drugs, but especially prazosin and calcium channel blockers |

| Anti-Parkinsonian drugs |

Neurological causes of syncope are associated with a slow recovery and often residual neurological symptoms or signs. Bystanders may also have noticed abnormal movements if the patient has epilepsy. Dizziness that occurs even when the patient is lying down or which is made worse by movements of the head is more likely to be of neurological origin, although recurrent tachyarrhythmias may occasionally cause dizziness in any position. One should attempt to decide whether the dizziness is really vertiginous (where the world seems to be turning around), or whether it is a presyncopal feeling.

Intermittent claudication and peripheral vascular disease

The word claudication

Popliteal artery entrapment can occur, especially in young men with intermittent claudication on walking but not running. Also, lumbar spinal stenosis causes pseudo-claudication: unlike vascular claudication, the pain in the calves is not relieved by standing still, but is relieved by sitting (flexing the spine) and may be exacerbated by extending the spine (e.g. walking downhill).

Risk factors for coronary artery disease

An essential part of the cardiac history involves obtaining detailed information about a patient’s risk factors—the patient’s cardiovascular risk factor profile (

Previous ischaemic heart disease is the most important risk factor for further ischaemia. The patient may know of previous infarcts or have had a diagnosis of angina in the past.

Hypercholesterolaemia is the next most important risk factor for ischaemic heart disease. Many patients now know their serum cholesterol levels because widespread testing has become fashionable. The total serum cholesterol is a useful screening test, and levels above 5.2 mmol/L are considered undesirable. Cholesterol measurements (unlike triglyceride measurements) are accurate even when a patient has not been fasting. Patients with established coronary artery disease benefit from lowering of total cholesterol to below 4 mmol/L. An elevated total cholesterol level is even more significant if the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level is low (less than 1.0 mmol/L). Significant elevation of the triglyceride level is a coronary risk factor in its own right and also adds further to the risk if the total cholesterol is high. If a patient already has coronary disease, hyperlipidaemia is even more important. Control of risk factors for these patients is called ‘secondary prevention’. Patients who have multiple risk factors for ischaemic heart disease (e.g. diabetes and hypertension) should have their cholesterol controlled aggressively. If the patient’s cholesterol is known to be high, it is worth obtaining a dietary history. This can be very trying. It is important to remember that not only foods containing cholesterol but those containing saturated fats contribute to the serum cholesterol level. High alcohol consumption and obesity are associated with hypertriglyceridaemia.

Smoking is probably the next most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease. Some patients describe themselves as non-smokers even though they stopped smoking only a few hours before. The number of years the patient has smoked and the number of cigarettes smoked per day are both very important (and are recorded as packet-years,

Hypertension is another important risk factor for coronary artery disease. Find out when hypertension was first diagnosed and what treatment, if any, has been instituted. The treatment of hypertension probably does reduce the risk of ischaemic heart disease, and certainly reduces the risk of hypertensive heart disease, cardiac failure and cerebrovascular disease. Treatment of hypertension has also been shown to reverse left ventricular hypertrophy.

A family history of coronary artery disease increases a patient’s risk, particularly if it has been present in first-degree relatives (parents or siblings) and if it has affected these people below the age of 60. Not all heart disease, however, is ischaemic; a patient whose relatives suffered from rheumatic heart disease is at no greater risk of ischaemic heart disease than anybody else.

A history of diabetes mellitus increases the risk of ischaemic heart disease very substantially. A diabetic without a history of ischaemic heart disease has the same risk of myocardial infarction as a non-diabetic who has had an infarct. It is important to find out how long a patient has been diabetic and whether insulin treatment has been required. Good control of the blood sugar level of diabetics reduces this risk. An attempt should therefore be made to find out how well a patient’s diabetes has been controlled.

Chronic kidney disease is associated with a very high risk of vascular disease. This is possibly related to high calcium-times-phosphate product and may be reduced by dietary intervention, ‘phosphate binders’, efficient dialysis, in renal transplant. Ischaemic heart disease is the most common cause of death in renal failure patients on dialysis.

The presence of multiple risk factors makes control of each one more important. Aggressive control of risk factors is often indicated in these patients.

It is interesting to note that in the diagnosis of angina the patient’s description of typical symptoms is more discriminating than is the presence of risk factors which only marginally increase the likelihood that chest pain is ischaemic. Previous ischaemic heart disease is an exception. Certainly a patient who has had angina before and says he or she has it again, is usually right.

Teeth

A history of dental decay or infection is important for patients with valvular heart disease, since it puts them at risk of infective endocarditis. Dental caries may also be associated with an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease. Ask about the regularity of visits to the dentist and the patient’s awareness of the need for antibiotic prophylaxis before dental (and some surgical) procedures.

Treatment

The medications a patient is taking often give a good clue to the diagnosis. Find out about any ill-effects from current or previous medications. The surgical history must also be elicited. The patient may have had a previous angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting, and may know how many arteries were dilated or bypassed. If the patient is unable to provide a history, a midline sternotomy scar and scars consistent with previous saphenous vein harvesting support this diagnosis.

Past history

Patients with a history of definite previous angina or myocardial infarction remain at high risk for further ischaemic events. It is very useful at this stage to find out how a diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease was made and in particular what investigations were undertaken. The patient may well remember exercise testing or a coronary angiogram, and some patients can even remember how many coronary arteries were narrowed, how many coronary bypasses were performed (having more than three grafts often leads to a certain amount of boasting). The angioplasty patient may know how many arteries were dilated and whether stents (often called coronary stunts by patients and cardiac surgeons) were inserted. Acute coronary syndromes are now usually treated with early coronary angioplasty.

Patients may recall a diagnosis of rheumatic fever in their childhood, but many were labelled as having ‘growing pains’.

Hypertension may be caused or exacerbated by aspects of the patient’s activities and diet (

Social history

Both ischaemic heart disease and rheumatic heart disease are chronic conditions that may affect a patient’s ability to function normally. It is therefore important to find out whether the patient’s condition has prevented him or her from working and over what period. Patients with severe cardiac failure, for example, may need to make adjustments to their living arrangements so that they are not required to walk up and down stairs at home.

Most hospitals run cardiac rehabilitation programmes for patients with ischaemic heart disease or chronic heart failure. They provide exercise classes that help patients regain their confidence and physical fitness, along with information classes about diet and drug treatment, and can help with psychological problems. Find out if the patient has been enrolled in one of these and whether it has been helpful. Is this service used as a point of contact for the patient if he or she has concerns about new symptoms or the management of medications?

The return of confidence and self-esteem are very important issues for patients and for their families after a life-threatening illness.

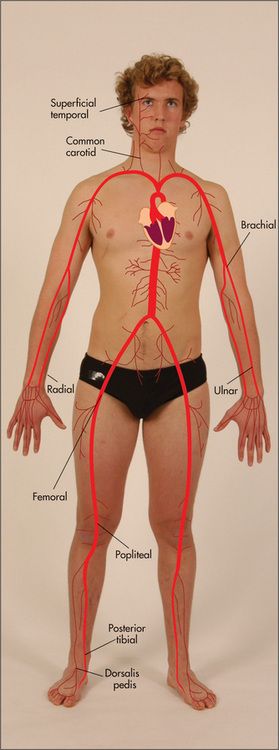

Examination anatomy

The contraction of the heart results in a wringing or twisting movement that is often palpable (the apex beat) and sometimes visible on the part of the chest that lies in front of it—the praecordium (from the Latin prae ‘in front of’, and cor ‘heart’). The passage of blood through the heart and its valves and on into the great vessels of the body produces many interesting sounds, and causes pulsation in arteries and movement in veins in remote parts of the body. Signs of cardiac disease may be found by examining the praecordium and the many accessible arteries and veins of the body.

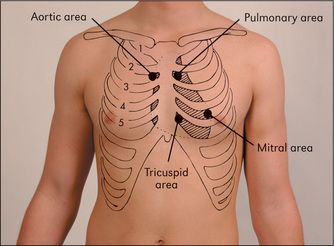

The surface anatomy of the heart and of the cardiac valves (

Figure 4.1 The areas best for auscultation do not exactly correlate with the anatomical location of the valves

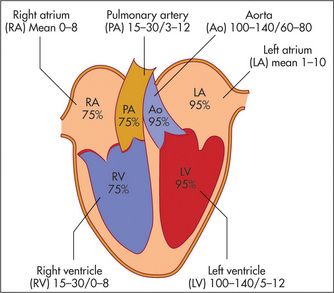

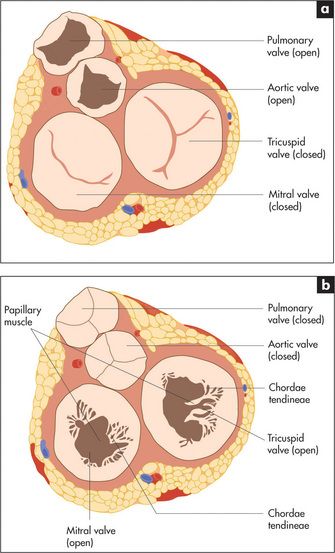

The cardiac valves separate the atria from the ventricles (the atrioventricular or mitral and tricuspid valves) and the ventricles from their corresponding great vessels.

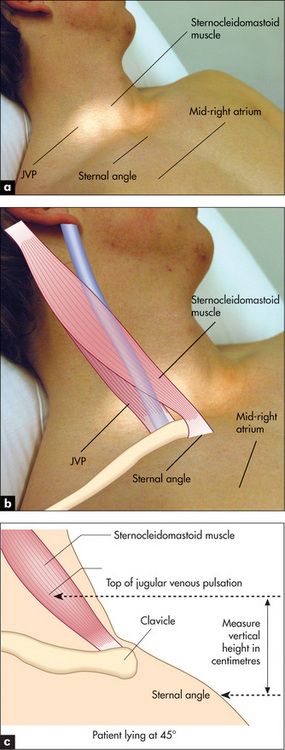

The filling of the right side of the heart from the systemic veins can be assessed by inspection of the jugular veins in the neck (

Figure 4.5 The jugular venous pressure (JVP) (a) Assessment of the JVP. The patient should lie at 45 degrees. The relationships between the sternomastoid muscle, the JVP, the sternal angle and the mid-right atrium are shown. (b, c) The anatomy of the neck showing the relative positions of the main vascular structures, clavicle and sternocleidomastoid muscle. See also

Figures (b) and (c) adapted from Douglas G, Nicol F, Robertson C, Macleod’s Clinical Examination, 11th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree