Chapter 9 The Breast

A. Generalities

(1) Inspection

9 Which areas should be examined?

Breast tissue is contained in an imaginary pentagon, whose lateral border follows the midaxillary line, from the middle of the axilla down to the inframammary (or bra) line (fifth to sixth interspace); the lower border crosses along the inframammary fold toward the xiphoid process; the medial border ascends the midsternal line toward the suprasternal notch; and the upper border follows the clavicle before turning down toward the midaxilla. This pentagon can then be divided into four quadrants (Fig. 9-1). Most cancers originate in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, and also below the areola and nipple, two areas containing a large amount of glandular tissue. Always inspect first and palpate later.

11 Which bedside maneuver can help to detect breast abnormalities on inspection?

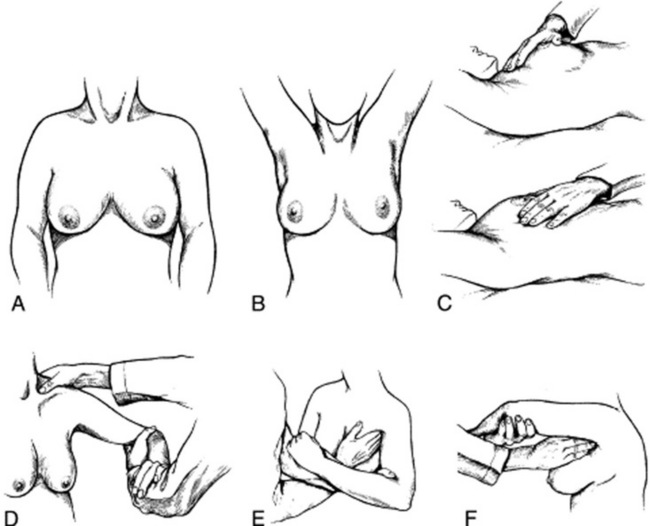

The most commonly taught and used maneuvers include a change in position of the patient’s arms and hands, first described by Haagensen (Fig. 9-2). To do so, ask the patient to carry out the following sequence:

1. >Rest the hands on the lap (to relax the pectoralis muscles).

2. Press them over the hips (to tense the pectoralis muscles and make dimpling and retraction more visible).

3. Raise them above the head, clasping them behind it (to also trigger skin dimpling, an important harbinger of cancer).

4. Lean forward (to allow the breasts to hang out pendulous from the chest).

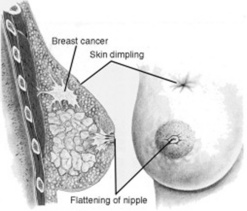

13 What is skin dimpling?

A slight depression or indentation in the breast’s surface (Fig. 9-3). This is an important clue to an underlying infiltrating carcinoma, causing fibrosis and retraction of the breast tissue. The same mechanism is responsible for nipple deviation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree