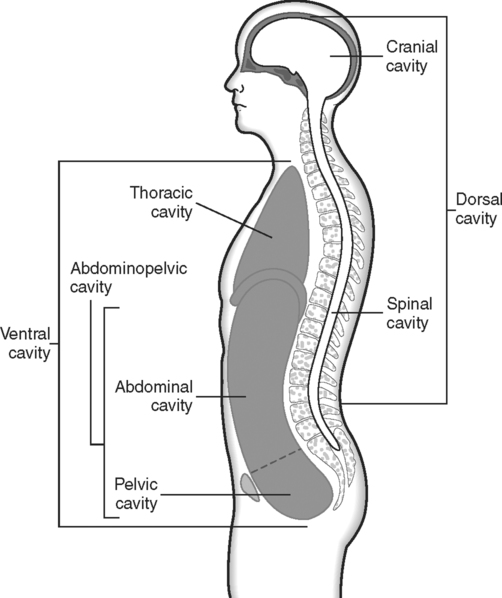

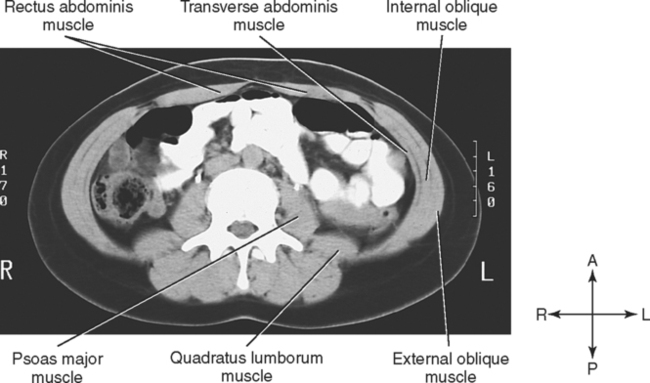

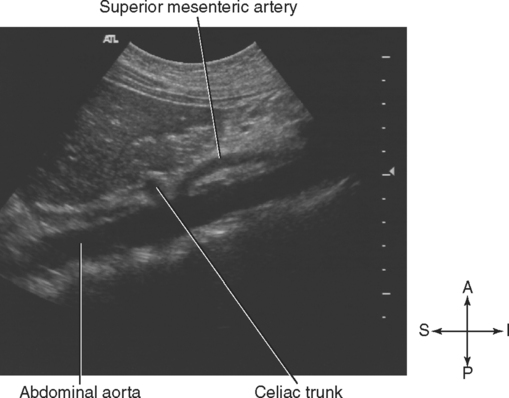

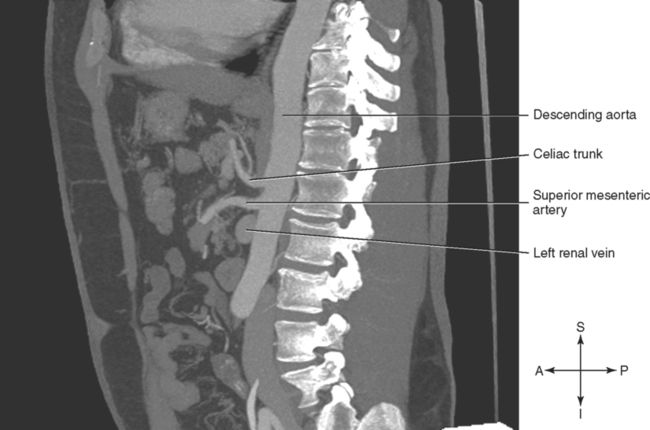

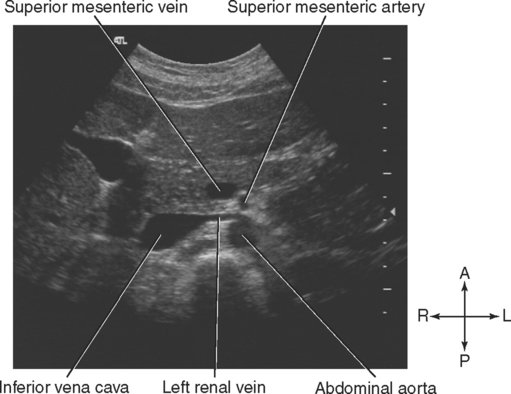

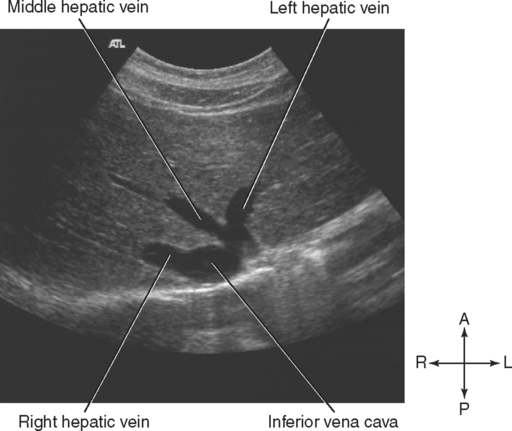

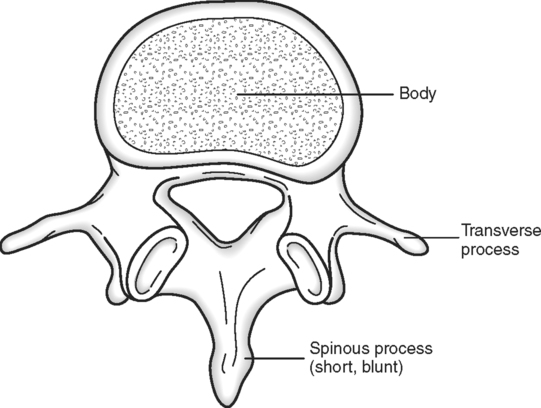

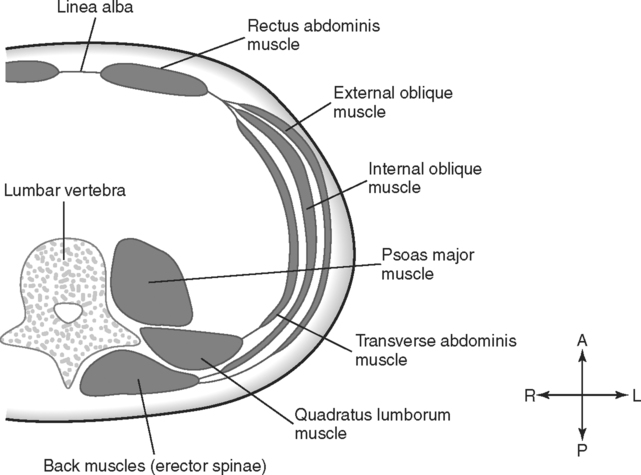

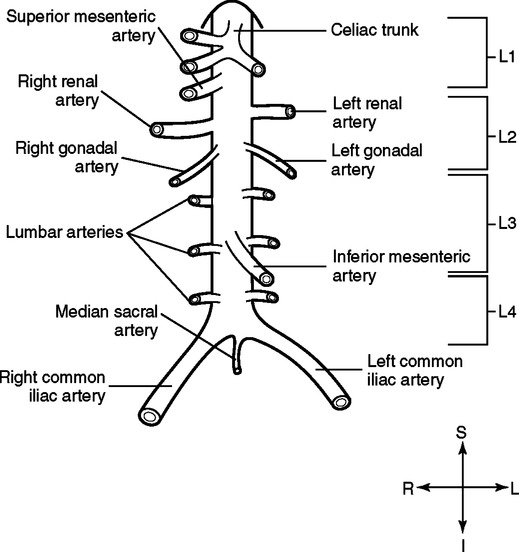

CHAPTER THREE Upon completion of this chapter, the student should be able to do the following: • State the boundaries of the abdomen. • Define the transpyloric, subcostal, transumbilical, interiliac, median, and midclavicular planes and then use these planes to divide the abdomen into four quadrants and nine regions. • Describe the features of lumbar vertebrae. • Describe the structure of the diaphragm, name and give the vertebral levels of the three major openings in the diaphragm, and identify the structures that pass through each opening. • Name the four muscles that form the anterolateral abdominal wall and the three muscles associated with the posterior abdominal wall. • Discuss the topography of the posterior abdominal wall and the effect this has on organ position and fluid accumulation. • State the level of origin of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta and identify the regions each one supplies. • Identify and trace the pathway of the tributaries of the inferior vena cava. • Trace the pathway of blood through the hepatic portal system of veins. • Discuss the peritoneum and its extensions, including mesentery, omenta, ligaments, and cul-de-sacs. • Discuss the structure and relationships of the liver, including its lobar subdivisions and blood supply. • Discuss the visceral relationships of the gallbladder. • Describe the external features of the stomach, its peritoneal extensions, its relationships, and its blood supply. • Name the regions of the small intestine and discuss the relationships of each region. • Identify the regions of the large intestine and discuss the relationships of each region. • Describe the location of the spleen and its relationship to other organs. • Discuss the location and relationships of the head, neck, body, and tail of the pancreas. • Describe the location and relationships of the kidneys, ureters, and suprarenal glands. • Identify the abdominal viscera, muscles, and blood vessels on transverse, sagittal, and coronal sections. Key Terms, Structures, and Features to Be Identified and/or Described Aortic hiatus Ascending colon Caval hiatus Common hepatic artery Epigastric region Esophagus External iliac vein Hepatic ducts Hypogastric region Iliacus muscle Inferior mesenteric vein Interiliac plane Left branch of the portal vein Pancreas, head, neck, body, tail Quadratus lumborum muscle R & L common iliac veins R & L kidneys R & L renal arteries R & L suprarenal arteries R & L suprarenal veins Rectus abdominis muscles Right gastric artery Splenic artery Subcostal plane Transumbilical plane Transversus abdominis muscle The ventral body cavity is divided into two distinct subdivisions that are separated by the dome-shaped diaphragm (Fig. 3-1). The upper portion, superior to the diaphragm, is the thoracic cavity. The lower portion, inferior to the diaphragm, is the abdominopelvic cavity. For the sake of convenience, the large abdominopelvic cavity may be divided into an upper abdominal cavity and a lower pelvic cavity. This is an artificial division, because no partition separates the two cavities, and some structures may move from one region to the other. Superficial landmarks are used to identify the various abdominal planes, which are used as indicators of vertebral levels and to describe the location of deeper structures. Vertical and horizontal planes divide the abdomen into regions, which are used to describe the location of organs or, in the clinical setting, the location of pain, tenderness, swelling, or abnormal growths. Five horizontal and three vertical planes are described. These planes are summarized in Table 3-1. TABLE 3-1 Horizontal and Vertical Abdominal Planes The right midclavicular plane extends vertically from the midpoint of the right clavicle to the midpoint of a line joining the right anterior-superior iliac spine and symphysis pubis, or midinguinal point. The left midclavicular plane is in the same position as the right midclavicular plane except that it is on the left side. It extends from the midpoint of the left clavicle to the left midinguinal point. The midsagittal plane, or median plane, is a vertical plane through the umbilicus. It divides the body into right and left halves. These planes are illustrated in Fig. 3-2. The transumbilical plane passes horizontally through the umbilicus. In individuals with relatively normal abdominal contour, this marks the level of the intervertebral disc between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. The interiliac plane passes through the most superior point of the iliac crests. This plane marks the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. The transtubercular plane passes through the tubercles of the iliac crests. The tubercles are small projections on the crests about 5 cm posterior to the anterior-superior iliac spine. This plane marks the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra. The horizontal planes are illustrated in Fig. 3-3. The horizontal transumbilical plane and the vertical median plane divide the abdomen into four quadrants for descriptive purposes. For example, the pain of acute appendicitis usually localizes in the lower right quadrant (see Fig. 1-6 for an illustration of the four abdominopelvic quadrants. Nine abdominal regions are described using the horizontal subcostal and transtubercular planes and the vertical right and left midclavicular planes. On the right and left sides the regions are, from superior to inferior, the hypochondriac region, the lumbar (or lateral) region, and the iliac (or inguinal) region. The three regions in the midline are, from superior to inferior, the epigastric region, the umbilical region, and the hypogastric region (see Fig. 1-7 for an illustration of the nine abdominopelvic regions). Five large lumbar vertebrae with their intervertebral discs form the skeletal support for the posterior abdominal wall. A lumbar vertebra (Fig. 3-4) has a large body with short, thick, blunt spinous processes. The transverse processes are also thicker than in other vertebrae. The shape of the lumbar vertebrae and discs gives a normal lumbar curvature that is convex anteriorly. This curvature develops during the second year as a child begins to walk and puts increased weight on the lumbar region. An exaggeration of or increase in the convex curvature is called lordosis. The anterior and lateral abdominal wall consists of four muscles and their aponeuroses with a covering of fascia and skin. The muscles, illustrated in Fig. 3-5 and by the computed tomography (CT) image in Fig. 3-6, are the rectus abdominis, the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transverse abdominis. The skin and muscles of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall are innervated by intercostal nerves. The second pair of muscles associated with the posterior abdominal wall is the pair of quadratus lumborum muscles. This thick muscular sheet originates on the iliac crest and transverse processes of the lower lumbar vertebrae and ascends to insert on the transverse processes of the upper lumbar vertebrae and twelfth rib. They are innervated by branches of the lumbar nerves. In transverse sections these muscles appear lateral and posterior to the psoas major muscles. The arrangement of the posterior wall muscles is illustrated in Figs. 3-5 and 3-6 with the anterolateral muscles. Examination of the posterior abdominal wall reveals a single longitudinal ridge and two oblique ridges. The longitudinal ridge line, sometimes called the longitudinal divide, is especially evident in transverse sections (see Figs. 3-5 and 3-6). It is formed by the lumbar vertebrae, the normal lumbar lordosis, the psoas major muscles, the inferior vena cava, and the aorta. On either side of the elevated longitudinal ridge is a paravertebral groove, or gutter. In superior regions of the abdomen, this groove is occupied by the liver on the right side and the spleen on the left side. The kidneys, ureters, and portions of the colon also are located in the paravertebral grooves. Whenever an organ crosses the midline, it is moved anteriorly because of the elevation of this longitudinal ridge. For example, the right lobe of the liver is rather posterior in position, whereas the left lobe is more anterior because it is moved forward by the longitudinal ridge. The pancreas offers another example of this anterior displacement. The tail of the pancreas is in a relatively posterior position, near the spleen. As the gland courses to the right, it is pushed forward by the longitudinal ridge so that the head and neck are more anteriorly situated. The abdominal aorta begins about 2.5 cm above the transpyloric line at the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm. At this level it is usually slightly left of the midline, but as the aorta descends, it assumes a more midline position. At the L4 vertebral level, marked by the interiliac line, the aorta bifurcates into the right and left common iliac arteries. The branches of the abdominal aorta may be divided into four groups: unpaired visceral, paired visceral, unpaired parietal, and paired parietal. The visceral branches supply the viscera or organs of the abdominal cavity, whereas the parietal branches supply the abdominal wall. The branches of the abdominal aorta are illustrated in Fig. 3-7. The second unpaired visceral branch of the aorta is the superior mesenteric artery. This vessel arises just below the transpyloric line at the level of the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra. It branches and anastomoses freely to supply all of the small intestine except the duodenum. In addition, it supplies the cecum, ascending colon, and most of the transverse colon. At its origin the superior mesenteric artery is separated from the aorta by the left renal vein. The splenic vein and body of the pancreas are anterior to the superior mesenteric artery. The sonogram in Fig. 3-8 and the CT image in Fig. 3-9 show the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery as they branch from the aorta. The renal veins drain the kidneys and empty into the inferior vena cava at the L2 vertebral level. They are usually anterior to the renal arteries, because the inferior vena cava is anterior to the aorta at this level. Because the inferior vena cava is to the right side of the midline, the left renal vein is considerably longer than the right. The left renal vein passes posterior to the splenic vein and the body of the pancreas. It crosses anterior to the aorta, just inferior to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery, so that the left renal vein is posterior to the superior mesenteric artery but anterior to the aorta. The sonogram in Fig. 3-10 shows the relationship of the left renal vein to the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta. The left renal vein receives the left gonadal (testicular or ovarian) vein and the left suprarenal vein before it enters the inferior vena cava. The right renal vein is slightly more inferior than the left because the right kidney is lower than the left kidney in position. The right renal vein passes posterior to the second or descending part of the duodenum. The hepatic veins drain blood from the liver and return it to the inferior vena cava. The central veins of the liver lobules collect blood from the intralobular venous sinusoids. The central veins merge to form the hepatic veins, which exit from the posterior surface of the liver and empty immediately into the inferior vena cava. Sometimes the right hepatic vein passes through the caval hiatus before entering the inferior vena cava. The sonogram in Fig. 3-11 shows the right, left and middle hepatic veins as they drain into the inferior vena cava. Blood from the digestive system is carried to the liver by a hepatic portal system of veins before it enters the inferior vena cava. Blood from the inferior mesenteric vein, superior mesenteric vein, and splenic vein enters the hepatic portal vein (Fig. 3-12). In the liver the hepatic portal vein branches until it ends in small, capillary-like spaces, called sinusoids, within the liver lobule. From the sinusoids the blood enters the central veins, which merge to form the hepatic veins as described previously. Four or five small vessels emerge from the hilus of the spleen and join to form a single splenic vein. As it courses to the right, inferior to the splenic artery and posterior to the body of the pancreas, the splenic vein receives numerous tributaries from the pancreas. The splenic vein terminates behind the neck of the pancreas, where it joins the superior mesenteric vein to form the portal vein. The CT image in Fig. 3-13 shows the formation of the portal vein.

The Abdomen

Anatomical Review of the Abdomen

Surface Markings

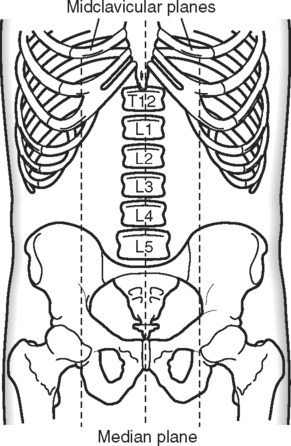

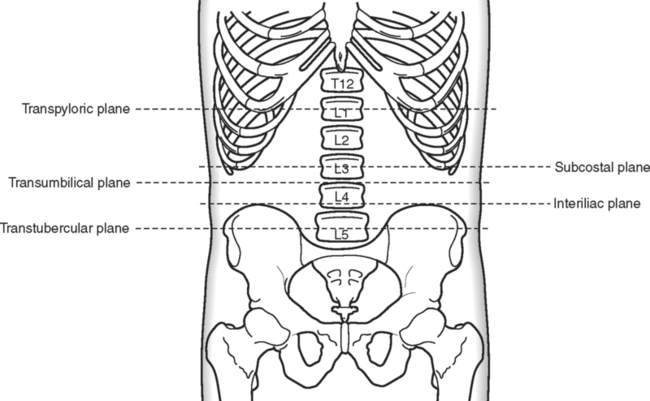

Abdominal Planes.

Plane

Description

Vertebral Level

Transpyloric

Horizontal plane halfway between the xiphoid and the umbilicus

Indicates vertebral level L1

Subcostal

Horizontal plane through the most inferior point of the rib cage

Indicates vertebral level L3

Transumbilical

Horizontal plane through the umbilicus

Indicates the disc between L3 and L4

Interiliac

Horizontal plane between the highest points of the iliac crests

Indicates vertebral level L4

Transtubercular

Horizontal plane between the tubercles of the iliac crests

Indicates vertebral level L5

Midclavicular

Vertical plane from the midpoint of the clavicle to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament; right and left

Median

Vertical plane through the umbilicus; divides body into right and left halves

Vertical Planes.

Horizontal Planes.

Abdominal Quadrants and Regions

Abdominal Quadrants.

Abdominal Regions.

Osseous Components

Muscular Components

Muscles of the Anterolateral Abdominal Wall.

Muscles of the Posterior Abdominal Wall.

Vascular Components

Vasculature of the Abdominal Wall.

Abdominal Aorta and Its Branches.

Unpaired Visceral Branches.

Inferior Vena Cava and Veins of the Abdomen.

Renal Veins.

Hepatic Veins.

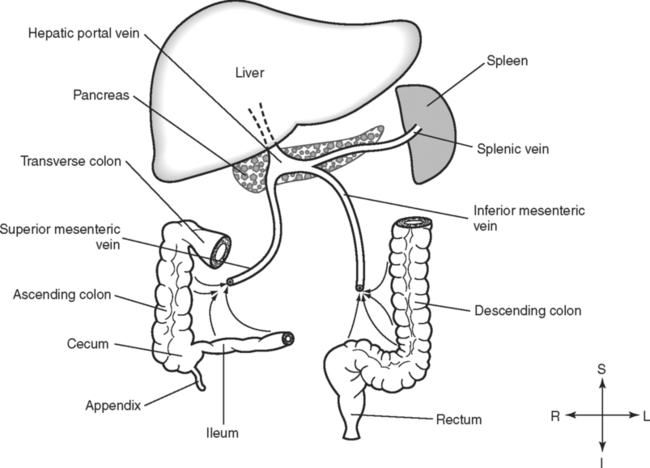

Hepatic Portal System.