6 The abdomen

At the end of this chapter you should be able to

1. Find, recognize and name the constituent bony components of the boundaries of the abdomen, including the lower ribs, cartilages, xiphoid process, lumbar vertebrae and pelvic girdle.

2. Palpate many of the bony features, being able to relate one to another.

3. Locate, name or number the spines and transverse processes of all the lumbar vertebrae.

4. Recognize and palpate the main bony landmarks of the pelvis, sacrum and coccyx.

5. Name all the joints of the lumbar spine and pelvis, noting their active and passive range of movement.

6. Give the class and type of all the joints named.

7. Palpate the joint lines, where possible, and give their surface markings.

8. Demonstrate any accessory movements which may be possible in the joints of the lumbar spine and pelvis.

9. Locate and name the muscles which surround the abdomen.

10. Draw the shape of the muscle on the surface and give its attachments.

11. Demonstrate the actions of all of the muscles covering the abdomen.

12. Give an account of their actions and functional significance.

13. Describe the main anatomical regions of the abdomen.

14. Give the surface markings of the liver, spleen, pancreas, gall bladder, small intestine, large bowel, kidneys and bladder.

15. Demonstrate the cutaneous distribution of the nerves covering the abdomen, giving an outline of the course each takes.

16. Describe the arrangement of the main arteries in the abdomen, giving their surface markings.

17. Describe the arrangement of the main veins in the abdomen, giving their surface markings.

Bones

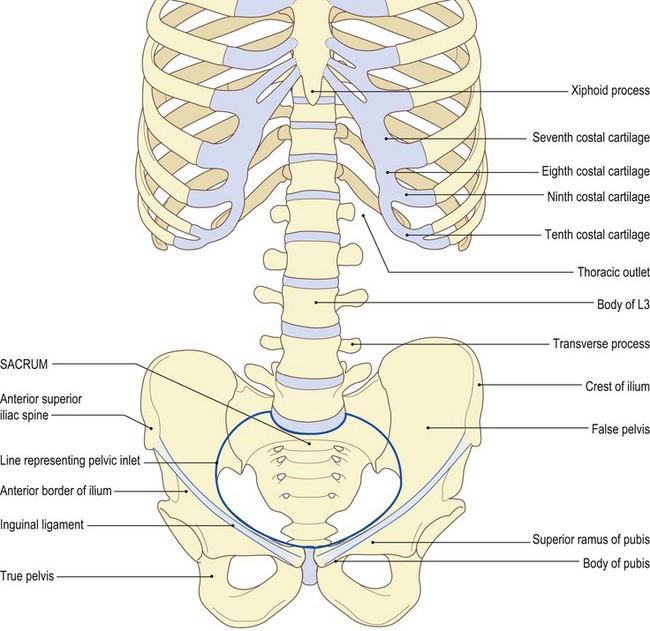

• above: the xiphoid process at its centre in the front, the lower border of the seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth costal cartilages, the tip of the eleventh rib and the inferior border of the twelfth rib

• posteriorly: the body of the twelfth thoracic vertebra completes the ring

• below: the pelvic inlet comprises the pubis anteriorly, its superior rami on either side, the anterior border and the crest of the ilium and posteriorly the base of the sacrum

The thoracic outlet (Fig. 6.1a, b)

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the supine lying position.

• The thoracic outlet. Find the xiphoid process, which is the most inferior portion of the sternum. Trace along the costal margin beyond the costal angle (the ninth costal cartilage) to its lowest extremity, which is normally the tenth rib. Continuing posteriorly, the eleventh rib becomes evident, with its tip just anterior to the mid-axillary line, with the tip of the twelfth rib slightly lower and just posterior. The tip of the twelfth rib normally lies on the same level as the spine of the first lumbar vertebra.

The pelvic girdle

Palpation

• The pelvic girdle. Identify the anterior superior iliac spine at the anterior extremity of the iliac crest. Trace the lateral lip of the iliac crest posteriorly, beyond the iliac tubercle to the posterior superior iliac spine and sacrum. Now, run the pads of your fingers down the central part of the abdominal wall to about 5 cm above the genitalia. The pubic tubercles become evident on either side, with each pubic crest running medially to a central space which marks the pubic symphysis. The bony ring is completed by the superior ramus of the pubis, which is difficult to palpate, and anterior border of the ilium, easily identifiable in its upper section. The inguinal ligament stretches above this region from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine.

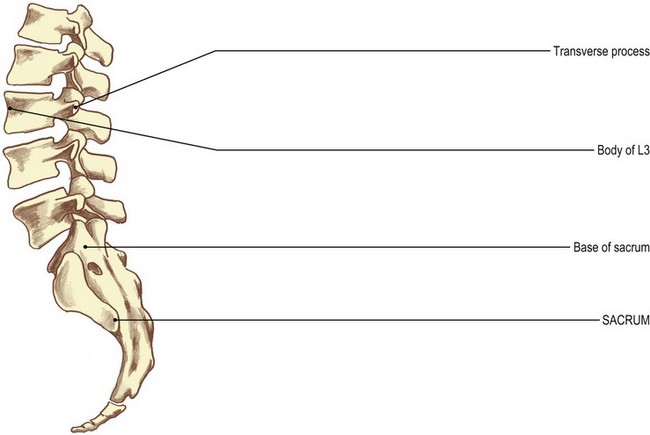

The lumbar vertebrae

Palpation

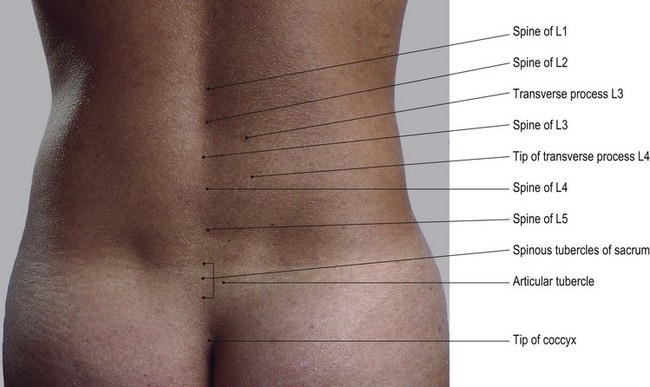

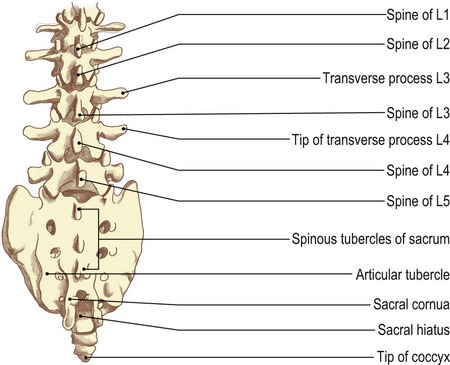

Posteriorly, the spines of the lumbar vertebrae project backwards and are individually identifiable.

For palpation in this region, the model is in the prone lying position.

• The lumbar vertebrae. Place a firm pillow under the abdomen which flattens the lumbar lordosis. This makes the spines of the lumbar vertebrae become more pronounced, appearing as a line of flattened edges forming a crest down the centre of the lumbar region (Fig. 6.1c, d). The spines are continuous with those of the sacrum below and the thoracic vertebrae above.

• The spines of the lumbar vertebrae. Immediately above the central part of the sacrum is a hollow, due to the spine of the fifth vertebra being shorter and the body being situated slightly more anterior than the rest. The small gaps between the spines tend to disappear when the vertebral column is flexed, owing to the tension of the supraspinous ligament.

• The transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. Apply deep pressure approximately 5 cm lateral to the vertebral spines beyond the bulk of the erector spinae muscles. Palpate the tips of the transverse processes.

• Note 1. The transverse process of the first lumbar vertebra is particularly easy to identify.

• Note 2. The transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae are relatively thin compared with those of the thorax and may be tender to palpate.

The sacrum

Palpation

• The sacrum. Identify the posterior surface of the sacrum between the posterior borders of the two ilia. Its lower section projects backwards and is easy to palpate. Its upper section (the base) lies more anterior and is more difficult to examine. Identify its central, vertical series of spinous tubercles which are in line with the lumbar spines and the coccyx. These are accompanied on either side by a row of articular tubercles which are all palpable (Fig. 6.1c, d).

The coccyx

Palpation

• Note. As the coccyx varies considerably in size and shape it may prove a little difficult to palpate. Several alternative methods can be employed:

• Note. In many subjects the coccyx is angled forwards and the finger must be pressed deep into the cleft to identify the shape. Care must be taken as pressure on the bone can cause pain, particularly if the joints between it and the sacrum have been damaged at any time.

Joints

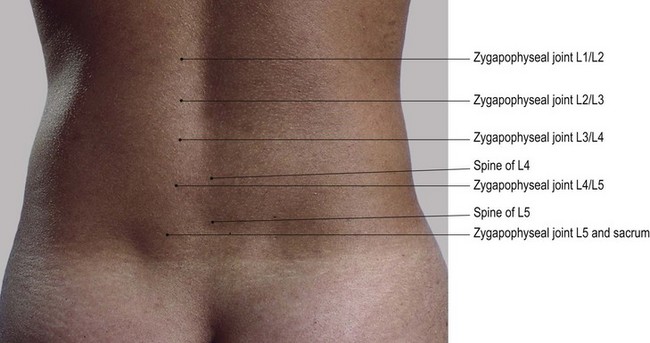

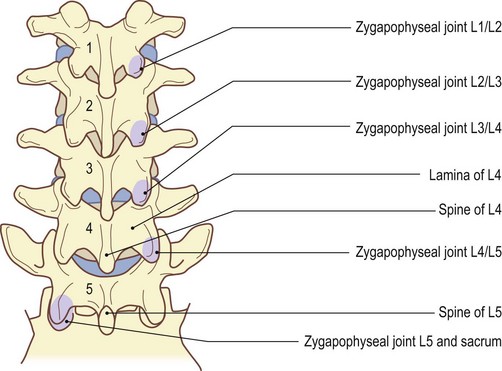

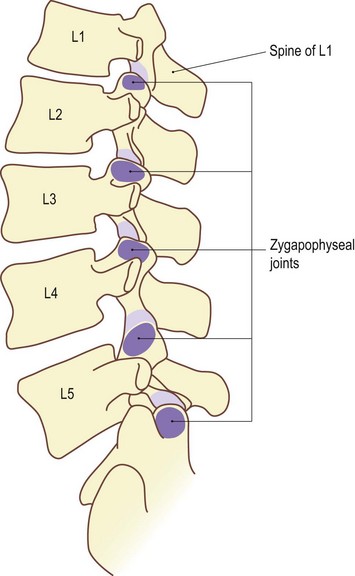

The lumbar spine (Fig. 6.2)

Palpation

For palpation in this region, the model is in the prone lying position.

• The zygapophyseal joints. Press your fingers between the sides of the vertebral spines and the parallel-running column of muscle (sacrospinalis). Identify the sides of each of the spines. In some subjects, it may also be possible to palpate the laminae of the vertebra. Each is a little higher than its corresponding spine, being almost totally hidden by the thick muscle layer.

• Posterior-anterior pressure. Using the tips of your thumbs, apply deep pressure through the muscle. This exerts pressure on the posterior aspect of the zygapophyseal joints, which lie 1 cm lateral and slightly lower than the vertebral spine. With great care and precision, this pressure can be targeted on to the upper articular pillar of the vertebra below by moving lateral to the joint, or on to the lower articular pillar of the vertebra above by moving just medial to the joint.

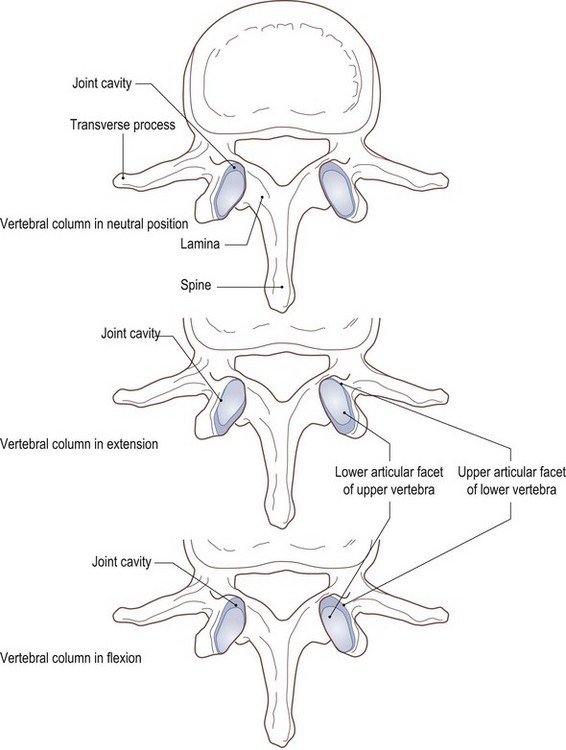

• Note. The lower facets of the vertebrae are convex anteriorly and fit snugly into the concave anterior edge of the upper facets of the vertebra below. Thus, anterior pressure on the lower vertebra causes its articular facet to glide forwards, slightly parting its anterior segments, whereas pressure on the upper vertebra pushes the lower facet into the socket, preventing any further movement (Fig. 6.2d, e).

Accessory movements

Palpation

• Distraction. Distraction (traction) of the joints of the lumbar spine is the only true accessory movement possible. All other movements of gliding, gapping and compression of the zygapophyseal joints, together with twisting and compression of the intervertebral discs, occur in the area during normal lumbar activities.

• Note 1. Traction can be applied to this area in many ways, either manually or mechanically. The lumbar column, however, can be placed in many different positions to achieve the therapeutic result required.

• Note 2. Extension of the lumbar spine tends to create a ‘close-packed’ position for the individual joints as the articular surfaces come into full contact and ligaments become taut. This, therefore, is not a desirable position in which to achieve traction. All other positions towards flexion allow space for the joint surfaces to part or glide. In full flexion, however, the ligaments again become taut, preventing the required movements. Traction in full flexion is almost impossible to apply.

• Note 3. The optimum position in which to apply traction is midway between extension and flexion.

• Note 4. Simple traction can be applied to the lumbar spine by applying a distraction force to either the pelvis or the lower limbs, with the subject lying either supine or prone. It is preferable to place a pillow under the abdomen in the latter position to prevent extension.

• Note 5. Manual traction can also be applied with the model sitting or standing. This is achieved by raising the upper trunk and allowing the pelvis and lower limbs to act as the traction force.

• Note 6. Mechanical traction can be applied in many positions of the lumbar spine, avoiding full extension and full flexion for the same reasons as outlined above. It may be applied continuously or intermittently over a set period of time. These therapeutic techniques are complex and need skill and knowledge of procedures and precautions. For further study, reference should be made to literature dedicated to this subject.

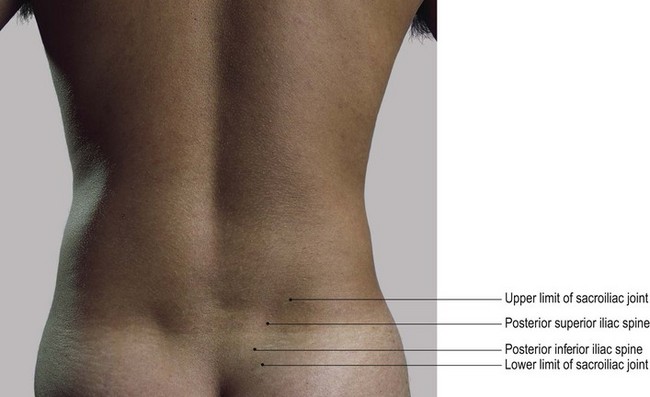

The pelvis (Figs 6.3 and 6.4)

Posteriorly, the sacrum articulates on either side with the ilium (innominate) bone at the sacroiliac joints (also discussed in Chapter 3). Anteriorly, the two pubic bodies articulate with each other at the pubic symphysis. The former is a very stable plane synovial joint supported by powerful interosseous and accessory ligaments. The latter is also stable, but is a secondary cartilaginous joint containing a modified disc of fibrocartilage. The sacroiliac joints allow a small degree of rotation of the sacrum, with respect to the innominate bones, about an axis through its interosseous ligament. Movement is more noticeable in young females, particularly during pregnancy and childbirth, reducing considerably after the third decade. In males, movement is negligible and virtually nil after the second decade.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree