Chapter 35 Teaching and learning clinical reasoning

´Clinical reasoning is widely acknowledged by different healthcare professions as a vital part of health professional education and effective practice. In fact, we would argue that clinical reasoning should be central to a health professional’s thinking development. It is now conventional wisdom that the term clinical reasoning and some of its associated vocabulary are included in major curriculum documents, in educational conversations and in practice descriptions. It has been incorporated into practice competency documents as a section in its own right (Bossers et al 2002). This chapter raises several key issues associated with teaching and learning clinical reasoning as a prelude to the more specific educational chapters to follow. They are:

ADDRESSING NEW INTERPRETATIONS AND PARAMETERS OF CLINICAL REASONING

Often the first task that faces educators is to understand the nature and context of the phenomenon they wish to teach. This is very much the case with clinical reasoning education. Of particular interest are the emergence of new models of interpreting and explaining clinical reasoning and the importance of practice context in understanding, facilitating and teaching clinical reasoning.

CHANGING INTERPRETATIONS AND PRACTICE OF CLINICAL REASONING

As with any new corpus of work, authors and researchers in this new era are now critiquing previous studies (Harries & Harries 2001, Paterson & Summerfield-Mann 2006), adding on to or refining existing frameworks (Chapparo 1999, De Cossart & Fish 2005, Paterson et al 2005), producing new perspectives and models (Hooper 1997), and becoming more sophisticated in ways of researching clinical reasoning and constructing early theories (Unsworth 2004). But, most critically, authors are also integrating into this original work associated bodies of knowledge such as creativity (Andresen & Fredericks 2001), adult learning theories and reflection (Refshauge & Higgs 2000, Ryan 2003), reflexivity (Finlay 2002), and world view and client-centred practice (Precin 2002, Unsworth 2004). With these integrations new perceptions are being merged into the original topic area, resulting in other dimensions of viewing clinical reasoning development.

For educators in the academy and in practice, the ways of guiding learning and reasoning development and the choice of clinical reasoning models to use will become more sophisticated as our understanding of this complex capability grows from continuing research studies and theoretical development. As discussed in Chapter 1, there is a growing emphasis on narrative, collaborative and interactive models of clinical reasoning in keeping with changing attitudes of society toward the input of patients and carers in clinical decision making. This has implications for the ways clinical reasoning will be construed and taught in the future and the ways it will be presented in a multitude of learning opportunities.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT IN CLINICAL REASONING

Major changes in the context of health professional practice are occurring worldwide (see Chapter 2). Increasingly, practitioners and students need to be able to deal with uncertainty in practice and to change their thinking and reasoning between different contexts. A new conceptual and interpersonal frame of reference for clinical reasoning and decision making is being drawn. And, as health practitioners are becoming increasingly more globally mobile, it is becoming more important that they become critical of themselves and their thinking and reasoning in practice or education within a dual frame of reference: they need to be locally informed and globally aware. The importance of firmly embedding thinking and reasoning in context is strongly emphasized in recent publications (Whiteford & Wright-St Clair 2005) and greater interest is being given to understanding the contextual factors that impinge upon and that need to be considered during clinical reasoning (Smith 2006) (see Chapter 8).

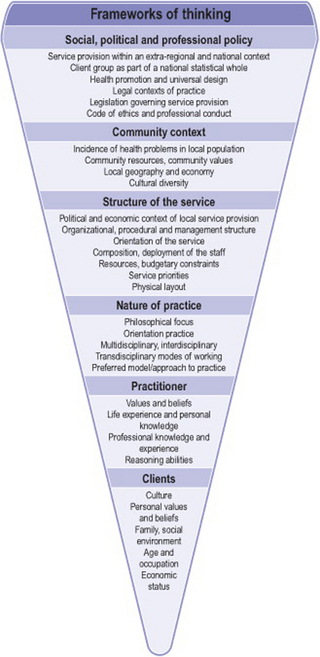

In Figure 35.1 we provide a framework for contextual reasoning that draws together these multiple contextual factors. This framework is a useful way to help students learn to think about reasoning in context. The use of this framework when situating case stories and case studies in the curriculum helps teachers to stimulate learners’ thinking about the wider implications of their practice decision making. The different levels of this framework range from broad to narrower contexts, from global to local. No levels are mutually exclusive. The complexities of the national and local picture surround the personal and professional frames of reference of individual students and practitioners.

Reasoning through these complex contexts and dealing with macro- and micro-dimensions of clinical reasoning calls for a more sophisticated mode of (and model for) reasoning than required by earlier interpretations of reasoning, such as problem solving and diagnostic reasoning. The psychologist Gelb (1996) has introduced the term synvergent thinking. This term describes this more sophisticated way of thinking, where there is a synergy between different levels of thinking and there is a synthesis of these in the reasoner’s mind. Local considerations such as guidelines and local rules are not removable from the larger context. To hold one idea and set of thinking simultaneously with thinking in a wider framework is a sophisticated and complex reasoning approach that suits the complexities and challenges of the current clinical practice context.

TEACHING REFLEXIVE LEARNING AND REASONING PRACTICES

These ideas are linked to the prelude or prospective thinking approach based on the ‘WHOLE – PART – WHOLE’ way of thinking and learning from adult learning theory (Knowles et al 1998). The prelude, the first WHOLE, is what the practitioner brings to the clinical encounter. This is the prospective section. Often, this can be understood hypothetically in university before actual practice experience. The subsequent PARTS occur in actual practice and the final WHOLE is a new set of understandings. This ‘final’ (that is actually the next prelude) may happen at the end of a practice experience, either while still in practice or when the learner is back at university. Such reasoning is holistic; it helps the practitioner to form a new lens for future practice. It can also be called meta-reasoning since it looks beyond and across particular practice and learning episodes to broaden the horizons of a health practitioner’s mind and help make subsequent practice episodes and experiences more realistic instead of idealistic.

UTILIZING RELEVANT EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES

There is considerable and ongoing debate in the literature and in educational practice about educational philosophies that can be used by teachers in the planning and implementation of health professional education to enhance the learner’s ability to engage in clinical reasoning. For example, for many years problem-based learning (PBL) has been heralded as the learning philosophy and strategy of choice for developing clinical reasoning. Learners have to search inductively for knowledge and then decide deductively and critically which material is relevant to use. In 2004, the European Network of Occupational Therapy in Higher Education (ENOTHE) espoused PBL as the learning method of choice. However, in Europe today, some of the first schools to adopt this PBL method, that have been using it for more than 20 years, are beginning to question its effectiveness. The practice competencies of these health practitioners are actually being questioned, as the learners struggle in practice settings to combine their largely academic reasoning with their actions.

This interesting debate needs closer and further examination. Savin-Baden (2000) determined that it was the way PBL questions were designed that lessened its effectiveness. Ryan (2003) found that while PBL helped to integrate knowledge better than subject-based learning, it was the way PBL was applied by educators that made the crucial difference between its being an effective learning philosophy or a waste of precious time.

One approach to addressing this dilemma is reshaping the teaching and learning strategy. Inquiry-based learning in Canada (Amort-Larson et al 1997) and task-based learning in Ireland (Ryan et al 2004) both integrate the PBL inductive methods of inquiry with new components added to the learning strategy; specifically, theoretical input from experts and required readings are incorporated, as well as an experiential element that is subsequently discussed and reflected upon in a feedback loop. These inquiries and tasks are set into guided learning experiences at regular intervals throughout the curriculum so that transferable knowledge, abilities and skills are developed alongside other transferable competencies. Learners appear to need these skills. As one student wrote: ‘I realized that analysing clinical reasoning was something I had the capacity and potential to do once I understood it more and realized that there was skill involved in this process’ (Student’s reflective diary – University College Cork (UCC) Clinical Reasoning postgraduate module).

We suggest that many learning philosophies can achieve this awareness of clinical reasoning skills as long as the educators design ways of learning that embrace the body of clinical reasoning knowledge and facilitate its development in the learner. Loftus & Higgs (2005) assert that there is a need to revise the theoretical basis of PBL to optimize the use of this curriculum and learning strategy. They advocate the adoption of a Vygotskian framework grounded in a cultural historical paradigm to enhance PBL interpretation and practice, explaining that Vygotsky’s ideas ‘revolve around the central thesis that human beings are products of their culture, and that individual psychological characteristics, especially higher level abilities such as the ability to engage in clinical reasoning, are derived from social interaction’ (p. 5). This framework recognizes the fundamental place of language and culture in the journey of acculturation that is health professional education, within which the learning of clinical problem solving and clinical reasoning occurs. These arguments support a review of the foundations of PBL to ensure that such curricula and learning activities are based on a solid foundation, an integrated approach to curriculum design and implementation.

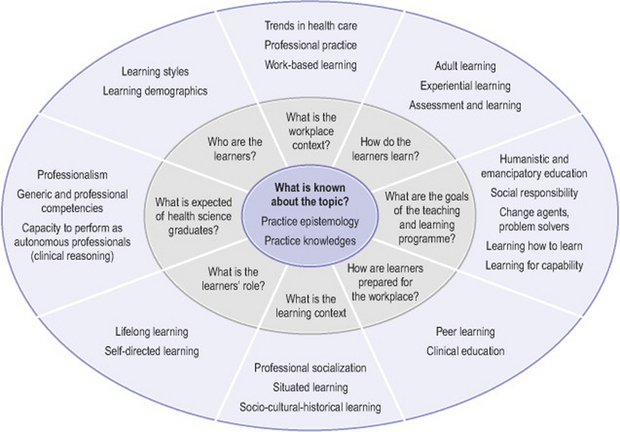

Figure 35.2 (from Higgs 2004) provides a framework for reviewing or planning strategies to promote the learning of clinical reasoning by relating key educational questions to educational theory and principles that can provide answers and guidelines for curricula. Inherent in the framework are two main arguments. The first is that there needs to be coherence between the intention, guiding principles, design, implementation and evaluation of curricula. Secondly, such curricular dimensions need to be made explicit to ensure this coherence and to communicate, realize and critique the curriculum intent and achievements.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree