Surgical Treatment of Pharyngeal Cancer

Bruce H. Haughey

Parul Sinha

The complexity of anatomical and physiological structure makes pharyngeal cancer surgery one of the most challenging tasks for head and neck surgeons. Cancer originating in each of the pharyngeal subsites—nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx—is unique in its biology, epidemiology, and response to treatment and merits a site-specific discussion of the appropriate surgical approach.

Nasopharynx

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas (NPC) are rare head and neck neoplasms characterized by marked geographical, environmental, and ethnic variations. The most recent report of the International Agency of Research on Cancer estimated the age-standardized rate (ASR) for NPC, worldwide, to be 1.7 per 100,000 males per year. Higher rates have been observed in South East Asia, particularly Southern China, and in certain other ethnic populations like Alaskans and Greenland Eskimos. A genetic susceptibility conferred by alterations in human leukocyte antigen typing or chromosomal patterns and environmental risk factors including

consumption of nitrosamine-rich salted fish have been postulated to play an important role in the etiology of NPC. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection has also been documented as a strong oncogenic precursor.

consumption of nitrosamine-rich salted fish have been postulated to play an important role in the etiology of NPC. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection has also been documented as a strong oncogenic precursor.

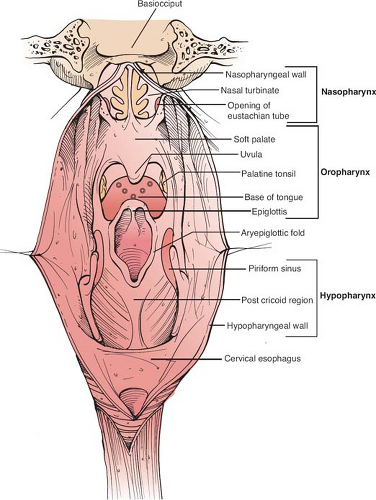

The nasopharynx (Fig. 1) is approximately a 4 × 4 × 2 cm space behind the posterior apertures of the nasal cavities (opposite C1 to C2) bound superiorly by the body of sphenoid, petrous apices, and basiocciput and inferiorly by the upper surface of the soft palate. The mucoperiosteum of the roof merges with the posterior soft tissue wall. The posterior wall consists of four layers that run across the entire length of the pharynx—from inside out, the mucosa, pharyngobasilar fascia, pharyngeal muscles, and bucco-pharyngeal fascia. The lateral walls of the nasopharynx contain the opening of the eustachian tubes (ET). Posterior and medial to the mucosal elevation formed by the ET opening (torus tubarius) is a deep recess, “fossa of Rosenmüller,” considered to be the commonest site for harboring NPC. The tumor may spread anteriorly from the fossa to block the ET opening. The proximity of this fossa to skull base structures and parapharyngeal space accounts for direct spread of disease across and through the skull base via invasion of the pharyngobasilar fascia. The nasopharyngeal mucosa is rich in lymphatics, with the lateral retropharyngeal group being the first echelon of nodes (uppermost known as node of Rouvière). The lymphatic disease spreads to the upper deep jugular nodes (level II) or the spinal accessory chain of nodes (level V). Lymphatics can also cross the midline to drain in the contralateral neck nodes.

Patients with NPC commonly present with painless metastatic neck mass(es), otologic symptoms such as conductive deafness, aural fullness, otalgia or tinnitus, and nasal symptoms including epistaxis or obstruction. Cranial nerve involvement can result in diplopia (VI, III, IV), facial pain or dysesthesias (V), palatal and vocal cord paralysis (IX, X), or Horner’s syndrome (sympathetic trunk). The characteristic symptoms of local tumor spread in NPC—conductive deafness, facial pain and palatal paralysis—are collectively referred to as Trotter’s triad.

A complete head and neck evaluation including rigid or flexible endoscopy with careful assessment of the posterior nasal space along with the examination of the cranial nerves should be performed. Radiological investigations including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are important to determine the extent and stage (Table 1) of tumor and also the appropriate surgical approach.

The radiosensitivity of NPC and restricted surgical access owing to the proximity of vital structures has made nonsurgical therapy the primary modality of treatment. The role of surgery is limited to salvage of recurrent or persistent cancer at the primary site without any intracranial spread or neck dissection. The size, location, and extent of tumor as well as involvement of the adjacent soft tissue determine the appropriate surgical approach.

Endoscopic

Small lesions without any lateral extension may be amenable to transnasal endoscopic excision but often, the exposure is not sufficient for oncological resection.

Transpalatal

Retraction or division of the soft palate can provide access to the nasopharynx. Wider exposure is achieved by detaching the soft

palate from the hard palate or by incising the palate in midline, which allows retraction after elevating the mucoperiosteum over the hard palate. These approaches need minimal reconstruction but provide limited exposure. For lateral wall tumors, surgical robot has been combined with transpalatal approach to enhance visualization and maneuverability of the instruments.

palate from the hard palate or by incising the palate in midline, which allows retraction after elevating the mucoperiosteum over the hard palate. These approaches need minimal reconstruction but provide limited exposure. For lateral wall tumors, surgical robot has been combined with transpalatal approach to enhance visualization and maneuverability of the instruments.

Table 1 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging of Pharyngeal Cancer (2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transcervical

An incision is made parallel to the lower border of mandible. Skin flaps are elevated and the mandible is retracted to expose parapharyngeal and nasopharyngeal space. A wider exposure is acquired through division of lip and mandibular symphysis.

Maxillary Swing

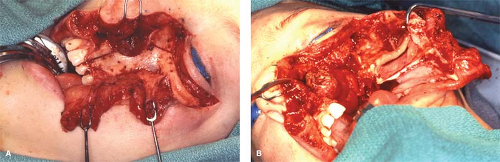

First described by Hernandez Altemir (1986), this approach provides a wide exposure for resection of nasopharyngeal tumor. A cheek flap is elevated to expose the anterior wall of maxilla. The osteotomy cuts are made below the roof of orbit, across the zygomatic arch, medial wall of maxilla below the middle turbinate, and hard palate in the midline. The pterygoid plates are removed from the maxillary tuberosity and after detaching all bony connections the whole maxilla is dropped inferiorly with the attached cheek flap for preserving vascular supply. The entire osteocutaneous complex is swung laterally to expose the nasopharynx for complete extirpation of tumor (Fig. 2).

Lateral

Fisch’s lateral infratemporal fossa approach can be used to remove tumors in the lateral nasopharyngeal region. The procedure includes a radical mastoidectomy, delineation and mobilization of the facial nerve and internal carotid artery, and division and displacement of zygomatic arch and the mandibular condyle with the muscular attachments to expose the infratemporal fossa. The mandibular branch of trigeminal nerve is divided and the bone at the middle cranial skull base is removed to access the nasopharyngeal space.

Palatal fistula may occur in transpalatal approaches, especially in irradiated patients. Maxillary swing approach can lead to ectropion, trismus, and/or malocclusion. The lateral approach is associated with significant functional morbidity including hearing loss and damage to cranial nerves V and VII.

Oropharynx

Introduction

Cancer of the oropharynx constitutes about 10% to 12% of all head and neck cancers and annually accounts for about 10,000 cases in the United States. The growing recognition of a disparate shift in its epidemiology, particularly in the Western world, has made oropharyngeal malignancy an intriguing clinical entity amongst all head and neck sites. The numbers of newly diagnosed oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC), mainly tonsillar and tongue base, are reported to be increasing in certain populations at an approximate rate of 4% and 2% each year, respectively. The rise is attributed to a strong etiological association with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) exposures. HPV-related OPSCC classically presents at younger ages and in persons with none or minimal tobacco exposure. The mode of HPV transmission is yet to be fully elucidated but high-risk sexual behaviors like orogenital contact and multiple lifetime partners are likely contributors.

The oropharynx is anatomically subdivided into (a) base of tongue, (b) tonsils and faucial pillars, (c) soft palate, and (d) pharyngeal wall (Fig. 1). Anteriorly, the oropharynx is demarcated by circumvallate papillae, junction of hard and soft palate, and the anterior faucial pillars. The bucco-pharyngeal fascia in the posterior pharyngeal wall (PPW) acts as a natural barrier to prevent the posterior extension of carcinoma. Lateral pharyngeal wall, palatine tonsils, and the faucial pillars delineate the lateral limits of the oropharynx. Inferiorly the oropharynx extends to the vallecula and includes the glossopharyngeal and pharyngoepiglottic folds. Absence of anatomic barriers between the subsites allows oropharyngeal tumors to spread locally in contiguity without restriction. Tumor extending through the lateral wall can involve the parapharyngeal space, including the pterygoid muscles and the carotid sheath structures. Waldeyer’s ring, a circumferential, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue ring in oropharynx comprising the lingual tonsils, palatine tonsils, and inferior part of adenoids, may give rise to primary tumors that metastasize at an early stage and often present as unknown primaries. A rich lymphatic network is responsible for the high probability of cervical metastasis from the oropharyngeal tumors. The primary echelon of drainage is the jugulodigastric nodes in the upper jugular chain (level II) and the retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal nodes. Lymphatic spread may advance from level II to middle jugular (level III) and lower jugular nodes (level IV). The medial base of tongue and other midline structures often drain bilaterally.

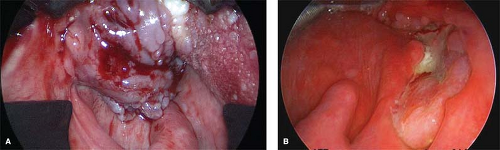

Oropharyngeal cancer tends to present at an advanced stage. Patients often present with a mass in the neck detected by direct observation or with symptoms of fullness in the primary site such as sore throat, otalgia, dysphagia, or trismus by which time the tumor has usually progressed to a significant size (Fig. 3). A frequent presentation of OPSCC, particularly submucosal tongue

base tumors, is in the form of an unknown primary, in which patients present with enlarged metastatic neck nodes but no clinically detectable or symptomatic primary tumor. OPSCC is also associated with a high incidence of distant metastases and synchronous primaries at the time of presentation.

base tumors, is in the form of an unknown primary, in which patients present with enlarged metastatic neck nodes but no clinically detectable or symptomatic primary tumor. OPSCC is also associated with a high incidence of distant metastases and synchronous primaries at the time of presentation.

A complete workup to assess the site and stage of primary tumor and presence of cervical lymphadenopathy is indicated. This includes history, physical examination, and a thorough head and neck evaluation including mirror examination, palpation, and office flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy for direct visualization. Radiological evaluation with a CT/MRI is performed to determine the extent of primary with greater accuracy as well as to assess the retropharyngeal metastasis. The cervical lymphadenopathy can be reliably assessed by Gray scale ultrasonography, supplemented by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration, if indicated. The latter is particularly useful in decision making for or against treating the contralateral neck. Chest radiography, CT, or positron emission tomography (PET) is used to evaluate distant metastasis or second primary tumors.

A systematic rigid pharyngolaryngoscopy examination under anesthesia (EUA) of the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) along with photo documentation should be performed to assess the primary tumor, detect synchronous primaries, obtain biopsies, and decide the ideal surgical approach—transoral or open. This procedure forms a significant component of tumor staging, treatment, and reconstruction planning. For patients with unknown primaries, a common mode of presentation for OPSCC, we employ transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) with traditional EUA, wherein the potential sites of occult primaries or other suspicious mucosal lesions are biopsied, followed by frozen section and finally by palatine and lingual tonsillectomies if no primary site is identified. The tumor is staged according to the American Joint Commission Cancer staging system based on all information gleaned from clinical, radiological, and endoscopic evaluations (Table 1). An evaluation of the patient’s dentition and necessary restorative dental procedures are also recommended prior to initiation of treatment.

Definitive surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy has been the cornerstone of curative treatment for OPSCC. Issues of organ preservation and functional morbidity subsequent to conventional open en bloc surgery have instigated advocation of nonsurgical management of OPSCC with chemoradiotherapy (CRT), a modality associated with modest survival outcomes and a higher acute and long-term toxicity profile. Rapid advances in technology have shifted the paradigm of surgical management of OPSCC toward minimally invasive endoscopic transoral approaches (Fig. 4). These approaches allow primary tumor-targeted treatment, minimal blood loss, rapid wound healing, avoidance of tracheostomy except for extensive oropharyngeal resections with flap reconstruction, better functional preservation, shorter hospital stay, faster rehabilitation, and also facilitation of a less morbid, pathologically stratified, risk-based adjuvant therapy. Biofactors like presence of HPV or its surrogate marker, p16, are reported to confer a favorable prognosis in surgically managed OPSCC. Other independently prognostic variables in such reports of advanced OPSCC were T stage, margins, and use of adjuvant radiotherapy. These findings bear strong implications for therapy of OPSCC in future. The decision for the optimal therapeutic modality is often taken by a multidisciplinary team based on tumor site and stage, patient preference, comorbidity, performance status, and available technical expertise.

Transoral Laser Microsurgery

Transoral carbon dioxide (CO2) laser microsurgery can be used for resection of both early and advanced stage tumor at all oropharyngeal subsites depending on the individual’s surgical skills and training. The basic requirements for TLM include a competent surgical training, knowledge of pharyngeal and neck anatomy “from the inside out,” good anatomic access, and strict enforcement of laser-specific precautions in the operating room. The core principles of TLM for oropharynx cancer, as first enunciated by Steiner, are summarized below:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree