Surgery of the Submandibular and Sublingual Salivary Glands

Carol M. Lewis

Michael E. Kupferman

Introduction

Surgery of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands requires an understanding of the anatomy of a small region of the human body. Surgical knowledge of this area for either preservation or safe extirpation of critical structures enables the surgeon to determine appropriate indications for surgical intervention and to competently perform such procedures. This holds true for trauma, infection, obstruction, or neoplasm. This chapter focuses on the indications for surgery, as well as surgical approaches to the sublingual and submandibular glands.

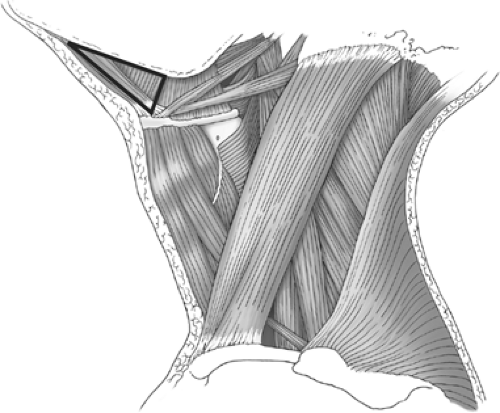

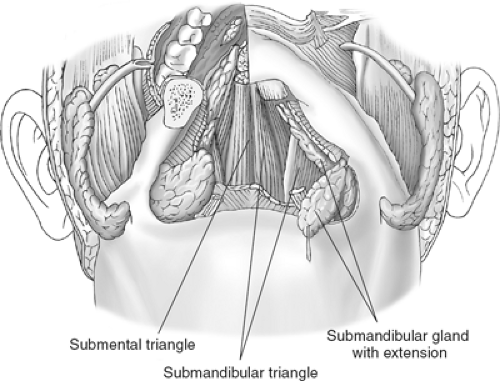

The mylohyoid muscle separates the sublingual space from the submandibular triangle. The sublingual space is bounded anteriorly and laterally by the mandible, superiorly by the mucosa of the floor of mouth, and inferiorly by the mylohyoid muscle. This space contains the sublingual gland and associated connective tissue, the hypoglossal nerve, and the deep portion of the submandibular gland (Fig. 1).

The submandibular triangle is bounded anteriorly by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, superiorly by the inferior border of the body of the mandible and the mylohyoid muscle, inferiorly by the trochlea and posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and posteriorly by the posterior border of the submandibular gland (Figs. 1 and 2). This triangle contains the submandibular gland and associated Wharton’s duct, lingual nerve and submandibular ganglion, hypoglossal nerve, and neurovascular bundle to the mylohyoid muscle. It is imperative to be familiar with these structures and their anatomic relationships both in neutral and surgical positions.

Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Evaluation

The evaluation of every patient begins with a thorough history and physical examination. Significant tenderness usually indicates acute infection, but can occasionally be attributed to neoplasms predisposed to perineural involvement, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma. Fluctuation of the size of the mass, most notably when eating, is a characteristic of an obstructed submandibular gland. Given the potential for disease metastatic to the lymph nodes of the submandibular triangle, any history of previous cancer is relevant; in addition to cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract, breast, lung, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, or cancers of the skin of the head and neck can metastasize to this region. Occasionally, squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity can involve the gland by direct extension.

Fig. 1. The submental triangle is bounded by the mandible, mylohyoid muscle (cut edge shown here), and superiorly by the oral mucosa. |

Prior to the specific examination of the submandibular triangle, a thorough head and neck examination, including inspection of the upper aerodigestive tract and the skin of the head and neck, is mandatory. Cervical palpation should be performed to identify any associated lymphadenopathy or masses in other levels of the neck. Bimanual palpation is a useful diagnostic maneuver to evaluate the floor of mouth or submandibular triangle, performed with one finger palpating intra-orally and the other hand assessing the mass from the neck. The mass should be evaluated for qualities such as tenderness, mobility, whether it feels cystic or solid, and whether it is single, multiple, or lobulated. In addition, intraoral palpation allows for evaluation of calculi along Wharton’s duct in cases of sialadenitis.

The utility of fine-needle aspirate biopsy (FNAB), often performed in conjunction with an ultrasound, is controversial. While an FNAB may provide a preliminary diagnosis, some may argue that surgical removal will be necessary regardless. However, if the FNAB reveals a salivary gland malignancy, the surgical approach should include a complete submandibular triangle dissection at minimum, and may also require a comprehensive neck dissection. Further, the patient may need to be counseled on the role of hypoglossal nerve resection, should a malignancy involve this structure. In addition, if the FNAB demonstrates carcinoma that is not of salivary gland origin, the work-up should involve identification of the primary tumor. Of note, FNAB is 80% to 90% sensitive for the diagnosis of salivary gland malignancies. Thus, FNAB findings may impact both work-up evaluation and surgical planning.

Computerized tomography can be helpful in determining if a mass is in, adjacent to, or invading the gland, as well as its cystic or solid qualities. It can also demonstrate other associated lymphadenopathy or, if the lesion is metastatic, the primary tumor. Alternatively, ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging scan may be performed. A sialogram is useful if obstructive sialadenitis is suspected.

The most common indications for removal of the submandibular gland are suspicion of neoplasm and chronic obstruction of Wharton’s duct by calculi with resultant sialadenitis. Neoplasms of the sublingual gland are rare, with most sublingual gland excisions being performed for ranulas.

Neoplasm

The incidence of salivary gland tumors in the general population is 2.5 per 100,000, representing 0.3% of all cancers and 1% to 3% of all head and neck tumors. There are various neoplasms that may involve the submandibular and sublingual glands; submandibular and sublingual salivary gland neoplasms represent 7% to 15% and <1% of all salivary gland tumors, respectively. Of these neoplasms, 40% to 50% of submandibular gland and >70% of sublingual gland neoplasms are malignant. The more common submandibular gland neoplasms and their defining characteristics are detailed here.

Pleomorphic adenoma (benign mixed tumor) is the most common benign salivary neoplasm, accounting for roughly 90% of benign submandibular gland neoplasms. Histologically, it contains mesenchymal, epithelial, and myxoid stromal components. This tumor is slow growing, nonpainful, and nontender, and can recur if not completely excised. It also has the potential for malignant degeneration, often heralded by rapid growth and/or neurologic symptoms.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common submandibular gland malignancy, comprising 15% to 43% of malignancies at this site; 47% extend through the capsule on presentation. A hallmark of this tumor is perineural invasion, such that postoperative radiotherapy is indicated with this

diagnosis. Patients must have at least a 10-year follow-up due to the frequent occurrence of delayed recurrence or distant metastasis; a 39% 10-year survival is expected. There are three histological varieties: cribriform, tubular, and solid; the solid variety carries a worse prognosis. This disease is associated with a high rate of local recurrence, and distant metastasis—most commonly, pulmonary occurs in ∼50% of patients. These patients have a median survival of 3.5 years after the identification of distant disease.

diagnosis. Patients must have at least a 10-year follow-up due to the frequent occurrence of delayed recurrence or distant metastasis; a 39% 10-year survival is expected. There are three histological varieties: cribriform, tubular, and solid; the solid variety carries a worse prognosis. This disease is associated with a high rate of local recurrence, and distant metastasis—most commonly, pulmonary occurs in ∼50% of patients. These patients have a median survival of 3.5 years after the identification of distant disease.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the second most common malignant tumor, comprising 17% of all submandibular malignancies. Histologically, it is composed of mucoid and epithelial elements; the higher the amount of the epithelial component, the higher the grade of the tumor. Low-grade tumors have a good prognosis (71% 5-year survival); high-grade tumors are more aggressive and are associated with worse prognoses. The latter usually requires postoperative radiation. Controversy exists regarding the outcomes of patients with intermediate-grade tumors, but emerging data suggests that these patients have favorable outcomes that approximate those with low-grade tumors.

Adenocarcinoma accounts for 11% of submandibular gland malignancies. Histological patterns include papillary, acinus, and solid; the amount of glandular elements determines the grade. These tumors are aggressive and tend to recur; intermediate- and high-grade histology usually indicates the need for postoperative radiotherapy.

Squamous cell carcinoma comprises 9% of submandibular gland malignancies. The differential diagnosis should include high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, metastases, and contiguous spread. There is a very poor prognosis (24% 5-year survival) associated with this disease and postoperative radiotherapy is generally indicated.

Malignant mixed tumor generally presents as a slowly growing mass that has a sudden increase in size, and accounts for 9% of all submandibular malignancies. The malignant component of the tumor may be undifferentiated carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma. A 56% 5-year survival and 31% 10-year survival are to be expected.

Undifferentiated carcinoma comprises <5% of submandibular malignancies. Histologically, this is a small cell tumor that may exhibit neuroendocrine differentiation. There is an elevated incidence in Greenlandic Eskimos, attributed to the Epstein-Barr virus. These tumors are very aggressive, characterized by significant local invasion, early distant metastases, and low survival rates.

Trauma

Isolated trauma in the submandibular triangle necessitating surgical intervention is rare, and usually involves neurovascular disruption caused by a sharp object. The vascular structures at greatest risk for such injury are the facial vessels. The nerves in jeopardy are the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, the lingual nerve, and the hypoglossal nerve. Bleeding from the facial artery can sometimes be so brisk as to suggest a carotid artery injury. Identification of the source for the hemorrhage is essential and is best obtained by a complete exploration of the triangle. The removal of the submandibular gland and identification of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle greatly facilitates this. Proximal control of the facial artery can be accomplished by dissecting just deep and inferior to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

With any exploration, all cranial nerves should be identified and their integrity assessed. The marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve is reliably located along the inferior edge of the horizontal ramus of the mandible within the fascia surrounding the facial artery and vein. The lingual nerve is located inferior to the mandible and deep to mylohyoid muscle; it is most easily identified with anterior retraction of the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle. The hypoglossal nerve should also be identified with anterior retraction of the mylohyoid muscle, since it is located deep to the plane of the lingual nerve and submandibular duct, and is usually flanked by veins. By identifying these nerves proximal or distal to the injury and dissection along their courses, the extent of the potential disruption can be ascertained and appropriate steps taken to repair them, if necessary. In the presence of edema, hematoma, or hemorrhage, this identification can be difficult and time-consuming. If there is only a preoperative suspicion of a neural injury, it is better to postpone any procedure and do the exploration at a later date, preferably within 7 to 14 days.

Sialadenitis

A submandibular or sublingual mass is most commonly sialadenitis caused by sialolithiasis. Eighty percent and 1% of salivary calculi occur in the submandibular gland and sublingual gland, respectively. A single stone is the cause in 75% of cases. If the calculus can be palpated along the course of Wharton’s duct intra-orally, an incision may be made just above the stone to release it. Medical management includes frequent massage of the gland, sialogogues, and hydration; antibiotics may be indicated if purulence is expressed from the duct with gland massage. Multiple recurrent sialadenitis with calculi can be treated with lithotripsy, sialoendoscopy with basket retrieval of stones, or excision of the submandibular gland.

Other causes of sialadenitis include neoplastic obstruction and ductal stenosis. The latter can be addressed using sialendoscopy with sialoplasty or with removal of the submandibular gland.

Ranula

The term ranula derives from the Latin word for frog, so named because of the appearance of patients with plunging ranulas. A simple ranula can be either a mucus retention cyst or pseudocyst from mucus extravasation that is confined to the floor of the mouth. A plunging ranula is a mucus extravasation pseudocyst arising from the sublingual gland that extends into the neck, either through the muscular dehiscence for the neurovascular bundle of the mylohyoid muscle or around the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle. This usually presents as a soft, cystic neck swelling. If any portion of the suspected ranula is solid to palpation, the possibility of a neoplasm should remain in the differential diagnosis. Also, although rare, lymphatic malformations should remain in the differential diagnosis, particularly in children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree