Surgery for Cancer of the Oral Cavity

William R. Carroll

In 1893, the 24th president of the United States set sail on a clandestine cruise from New York to his summer home in Massachusetts. On board, physicians had transformed the deck to a makeshift operating room. Grover Cleveland was anesthetized and a malignant oral cavity tumor was resected. The president recovered and lived another 16 years. The operation was later described as a remarkable procedure for the time. Ulysses Grant, Sigmund Freud, George Harrison, and Sammy Davis Jr. all suffered from oral cancer.

Incidence, Mortality, and Etiology

Worldwide, oral cavity cancer is the sixth most common cancer type. The American Cancer Society estimates that 28,500 new cases of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx occurred in the United States in the year 2010. Approximately 7,600 die of the disease. The mean age at diagnosis is 63 years and over 70% of patients are male. Unfortunately, the overall survival rates for oral cancer have not improved significantly in the past 20 years. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data from the National Cancer Institute reveal that the overall 5-year survival rate is 61.2. Racial/ethnic disparity for oral cancer is among the most striking of all cancer types and is most evident among men. Five-year survival rates are 63.7% for white men and 38.3% for black men. Causes of the disparate survival rates likely include comorbidities, later-stage disease at presentation, differences in treatment received, and possible biologic differences in the tumor and host.

Eighty to ninety percent of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinoma. Roughly 90% of patients use tobacco in some form and 75% use alcohol. The effect is synergistic and the relative risk of developing oral cancer is increased 16-fold for individuals who use both. The risk of developing a second primary tumor is also dramatically increased in those who continue to smoke following initial treatment (37% vs. 6% risk).

Disturbing cases of oral cancer are also seen in patients without obvious risk factors. Other possible causes include prolonged minor trauma from poor dentition, a diet low in fruits and vegetables, immunosuppression, and exposure to the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV subtypes 16 and 18 are closely linked with cervical cancer and are implicated in 15% to 20% of oral and oropharyngeal cancers. These cancers more commonly arise in the oropharynx than in the oral cavity, often involving the oral cavity by direct extension. HPV-related cancers often develop in younger patients and have a better prognosis than non-HPV tumors. Cancer of the lip is classified with oral cancer and is strongly correlated with sun exposure in fair-skinned individuals. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, transplant recipients, and others who are immunocompromised by disease or medical therapy are at increased risk for oral cancer. The cancers that occur in these individuals are unfortunately biologically very aggressive.

Genetic changes within the oral mucosa are measurable well before the development of invasive carcinoma. Chronic exposure to carcinogens damages DNA over the mucosal field. The “field effect” of altered mucosa may be evident as far as 7 cm from an established malignancy. These alterations may activate or amplify oncogenes that promote tumor cell proliferation and inhibit or inactivate tumor suppressor genes. Tumor cells are able to escape programmed cell death and proliferate self-sufficiently. Seventy to eighty percent of oral premalignant lesions contain changes in chromosome 9p21, which encodes the

tumor suppressor genes p16 and p14ARF. The epigenetic process of methylation of these genes is the apparent mechanism of inactivation. Mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene has received much attention in the literature but is probably a later event in malignant transformation. p53 mutations at the margin of resection have also been correlated with increased rate of recurrence despite histologically clear margins.

tumor suppressor genes p16 and p14ARF. The epigenetic process of methylation of these genes is the apparent mechanism of inactivation. Mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene has received much attention in the literature but is probably a later event in malignant transformation. p53 mutations at the margin of resection have also been correlated with increased rate of recurrence despite histologically clear margins.

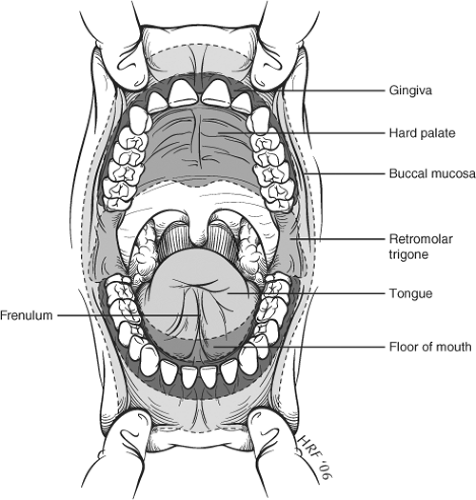

The oral cavity extends from the vermillion border of the lips to the anterior tonsillar pillar (Fig. 1). For staging purposes, the following subsites are considered part of the oral cavity: lip, oral tongue (anterior two-thirds), floor of mouth, buccal mucosa, upper and lower alveolus, hard palate, and retromolar trigone. The oral cavity has rich lymphatic supply and regional nodal metastases are typically the first site of spread. The primary lymphatic drainage basins are the perifacial, upper jugular, submandibular, and submental nodes. Sites close to the midline often drain bilaterally.

The most common symptom of oral cancer is a nonhealing ulcer in the mouth followed by persistent pain. Other common symptoms include a mass, persistent halitosis, or bleeding. Trismus, loose teeth, neck mass, and difficulty with speech or swallowing usually indicate more advanced disease. When symptoms persist longer than 3 weeks, a focused examination for oral cancer is imperative.

Oral cancer arises most commonly in the floor of mouth, followed by the lateral tongue. The distribution by site is summarized in Figure 1. Diagnosis is usually made in the office by simple physical examination and biopsy using local anesthesia. Oral cancer is often very curable when detected at an early stage. The same is not true of later-stage disease. The ease of examination and access for biopsy make late recognition of disease particularly regrettable.

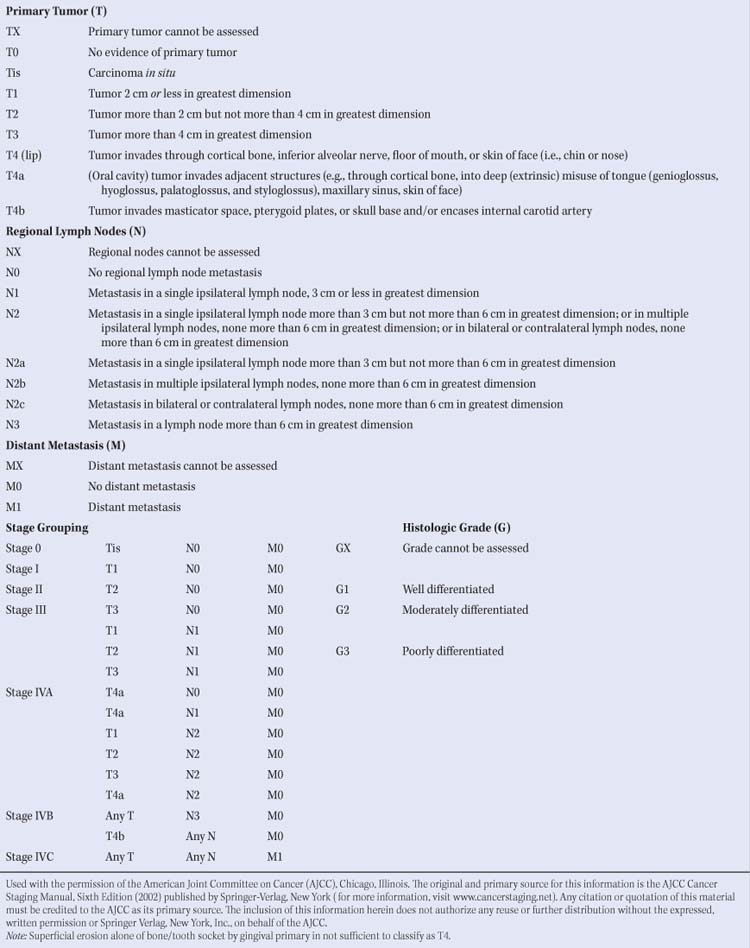

Oral cavity cancers are staged according to 7th edition (2010) American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines. T1 to T3 tumors are staged only on the basis of size (Table 1). T4 tumors are subdivided into T4a and T4b according to the degree of invasion of surrounding structures and ultimate resectability. The TNM staging system does not yet include depth of invasion as a staging variable for oral cavity tumors. Many investigators have shown, however, that depth of invasion correlates directly with frequency of nodal metastasis. Most surgeons feel that a T1 tumor with a depth of invasion greater than 4 mm has a greater chance of developing nodal metastases than a T2 or T3 tumor that is very superficial.

The staging workup for oral cavity tumors includes a complete physical examination with focused mucosal examination of the upper aerodigestive tract and careful nodal examination. Careful palpation of the oral cavity is crucial in the staging workup as many of these tumors have unsuspected submucosal extension (particularly tongue cancers). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the primary site and neck may assist accurate locoregional staging. A search for distant metastases includes a chest radiograph and liver function tests at a minimum. CT scans of the chest and abdomen are indicated in patients considered to be at higher risk of distant disease. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans are not considered a routine part of the staging workup for head and neck cancer at this time. Because second primary tumors are detected in about 10% of patients, an examination under anesthesia (direct laryngoscopy, esophagoscopy) is performed prior to treatment initiation. Bronchoscopy is recommended only for patients with evidence of subglottic disease, persistent cough, or suspicious chest radiography findings.

Imaging techniques designed to detect dysplastic changes in oral mucosa may ultimately improve early detection and margin control for oral cavity cancer. Confocal microscopy, radiolabeled antibodies to tumor markers, narrow band imaging, and multiwavelength fluorescence and reflectance technology are technologies designed to detect subclinical disease in at-risk patients or to identify dysplasia at the margins of known cancers.

Current treatment guidelines for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma are published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (www.nccn.org). The guidelines include staging information, recommendations for pretreatment assessment, and a balanced approach to treatment options for oral cavity cancers. Optimal treatment of head and neck cancer requires a multidisciplinary effort. Team members include a head and neck surgeon, reconstructive surgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist. Speech and swallowing pathologists rehabilitate function lost during multimodal therapy. Other important team members include dentists, prosthodontists, nutritionists, and social workers. For patients with advanced or recurrent disease, treatment recommendations are optimally considered in a multispecialty tumor-board format. A coordinated team approach is essential.

Table 1 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging System for the Lip and Oral Cavity | |

|---|---|

|

In this chapter, treatment of oral cancer will be divided into two main sections: A general discussion of early-stage and locally advanced disease followed by specific recommendations for each subsite. The primary focus is surgical management. Alternative options will be included but detailed descriptions are beyond the scope of this chapter. Treatment of metastatic neck disease is covered elsewhere in this text and is integral to proper management of the primary site.

Carcinoma in Situ or Microinvasive Carcinoma

Early, very superficial disease within the oral cavity is best treated by wide local excision. When disease is limited to carcinoma in situ on final pathology, an excisional biopsy with clear margins is adequate therapy. The site should be followed closely clinically with a low threshold for rebiopsy or reexcision. Microinvasive carcinoma should be excised with a 1- to 2-cm margin on the peripheral and deep aspects. Frozen sections are studied intraoperatively as severe dysplasia at the margin can be difficult to discern grossly (Fig. 2). Early-stage cancers of the floor of the mouth may involve the salivary ducts, and gain early access to the neck. The nodal status requires careful assessment.

Primary closure of the site is optimal if it can be accomplished without tethering the tongue or obliterating normal sulci. The surgeon should have little hesitation to allow these superficial defects to granulate. Healing by secondary intention is preferable to a closure that impairs mobility. Occasionally, a larger but very superficial lesion will be excised at the submucosal layer. A thin split-thickness skin graft will cover a larger area effectively and speed the recovery process. Commercially available dermal allografts have been uniformly unsuccessful in the oral cavity in our hands.

T1 and T2 Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity

Five-year survival rates are 85% to 90% for stage I and 70% to 80% for stage II squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. Single-modality therapy is usually adequate. Surgery and radiotherapy are generally considered equally effective but in most cases surgery is preferred for early-stage disease. Radiation therapy for early-stage oral cavity cancer is effective when delivered by either external beam or brachytherapy. Xerostomia and dental disease are more commonly seen following radiotherapy and there is risk of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Few studies have critically compared functional outcomes of radiation therapy with surgery. Whichever modality is chosen, treatment of the primary site and neck should be consistent. In other words, if the primary site is treated surgically and there is concern over micrometastases, the neck should be treated surgically as well. Likewise, if the oral cavity is treated with radiation, the lymphatics are treated similarly.

Surgical treatment for stage I and II oral cavity cancer is consistently recommended initially by our institution’s multispecialty tumor board. Surgical treatment is effective and completed quickly with minimal impairment of form or function. The typical hospital stay is one or two nights, oral intake is resumed quickly, and patients typically resume full activity within 3 weeks. Even those individuals with occupations demanding precise oral function (attorneys, professors, salespersons) have typically enjoyed very favorable outcomes.

In planning resection, the surgeon must consider route of access, margin status, bone involvement, and whether or not lymphatics require treatment. Route of access is preferably transoral for smaller lesions. The margins must be clearly visible, however, and patients with full dentition or limited oral opening can present access challenges for even small lesions. A lip split and/or mandibulotomy may be required for adequate visualization of margins. Margins of 2 cm on all sides are ideal for these lesions.

As a word of caution, the first attempt at removing these lesions has the greatest chance of success. Each subsequent attempt at salvage has a decreasing yield. To withhold a full curative effort for a minimal cosmetic or functional benefit is a disservice to the patient.

Bone will not be grossly invaded in these early-stage I and II lesions, though dysplastic mucosa or the main malignancy may approach the teeth or mandibular periosteum. In general, the periosteum is an effective barrier if not previously radiated. If the tumor is freely mobile with relation to the bone, the periosteum is resected as a margin and the bone preserved. The alveolar surface of the mandible is vulnerable to microinvasion and allows access to the medullary cavity through the tooth sockets. The risk of microinvasion of the mandible is higher in an edentulous or previously radiated mandible. When tumor directly invades the periosteum, that segment of mandible should be resected with at least a rim mandibulectomy.

The risk of micrometastasis to cervical lymphatics is increased proportionally with the depth of tumor invasion. As a general rule, tumors that measure greater than 4 mm in thickness are at risk, and treatment of cervical lymphatics should be considered.

T3 and T4 Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity

Large oral cavity cancers and those that deeply invade the tongue, bone, or adjacent spaces require multimodal therapy. Survival rates for T3 and T4 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity are 50% to 65% in the absence of nodal metastases. Nodal metastases generally cut survival rates in half. Primary surgical resection remains the preferred initial treatment option. In contrast,

advanced oropharyngeal malignancies are often treated initially with chemoradiation. When planning resection, the surgeon again must consider the lymphatics, access, bone involvement, and reconstruction as these defects can rarely be closed primarily.

advanced oropharyngeal malignancies are often treated initially with chemoradiation. When planning resection, the surgeon again must consider the lymphatics, access, bone involvement, and reconstruction as these defects can rarely be closed primarily.

Surgical treatment of the neck to control lymphatic disease and to provide access to the primary tumor is routine. Rarely can a T3 or T4 lesion be adequately resected by a transoral-only approach. Exposure of the neck allows preservation of important neurovascular structures and facilitates management of the deep margin of resection. Well-lateralized lesions that do not involve the deep tongue muscle may be adequately managed with a unilateral neck dissection. Clinically N0 necks are treated with a selective neck dissection, which carries very little morbidity (see Chapter 26). Edentulous patients with pliable perioral soft tissue may not require a lip split for access from the oral side. Again, if visualization of the margins is impaired, lip split or mandibulotomy is recommended as necessary to allow proper exposure. Complete tumor resection should be the primary concern.

Gross invasion of the mandible mandates a segmental resection. Whenever possible, the entire medullary cavity of the mandible should be resected. Tumor invading the mandible can spread widely through the loose cancellous bone. For example, if a lesion invades the midbody of the mandible, segmental resection of bone with a 2-cm margin is combined with rim removal of the remaining medullary cavity back to the sigmoid notch.

Reconstruction will often require more than primary closure. In some lateral composite resections, surprisingly large defects can be closed primarily when no bone reconstruction is planned. The disfigurement is pronounced, however, and most patients prefer immediate surgical reconstruction. Return of a more normal appearance and ability to chew are important aspects of quality of life. Large glossectomy and full-thickness buccal defects cannot be closed without supplemental tissue. Vascularized free tissue transfer has become the mainstay of surgical reconstruction for large oral cavity defects. Soft tissue defects are usually repaired with radial forearm, lateral thigh, or rectus abdominus flaps. Mandibular defects are managed with osteocutaneous flaps, the fibular flap being the most common.

Site-Specific Surgical Management

Floor of Mouth

The floor of mouth is the most common site for oral squamous cell carcinoma. The adjacent ventral tongue and lingual surface of the mandibular alveolus are involved early as the tumor enlarges. Anteriorly, floor-of-mouth lesions often involve the submandibular ducts and contralateral nodes are at risk. CT scans are useful in preoperative staging to assess tumor extent, nodal status, and early mandibular invasion.

T1 and T2 Carcinoma of the Floor of Mouth

T1 and T2 lesions of the floor of mouth are treated with wide local excision (Fig. 3). A margin of 2 cm is recommended and frozen section control of margins intraoperatively may avoid overlooking severe dysplasia in surprisingly normal-appearing mucosa. Lesions deeper than 4 mm have a higher incidence of nodal metastasis and an elective selective neck dissection should be considered. Transoral access without lip split or mandibulotomy is often possible. Full dentition or poor oral opening can make access surprisingly difficult for small lesions. The patient should be prepared for mandibulotomy for access should this occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree