Subtotal Gastrectomy for Cancer

Vikas Dudeja

Patrick G. Jackson

Waddah B. Al-Refaie

DEFINITION

Subtotal gastrectomy is removal of 70% to 80% of distal stomach. This is performed when the necessary 5- to 6-cm proximal margin can be obtained while maintaining a gastric remnant of reasonable size.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Presentation

In United States, gastric cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage and nearly 65% of patients harbor nodepositive disease.1,2 The most common symptoms are weight loss, anorexia, and early satiety. Some of these symptoms overlap with those of benign peptic ulcer disease. Patients with distal gastric cancer may present with symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction, including postprandial vomiting and weight loss. Patients may also present with progressive abdominal distension secondary to malignant ascites.

Special attention should be paid to weight loss. Although this may reflect metastatic disease or gastric outlet obstruction, in patients with resectable disease, it signifies a need for preoperative nutritional optimization. Specifically, patients with more than 10% weight loss are at increased risk of perioperative complications.

Attention to pretherapy performance status is critical, as this correlates well with ability to tolerate various oncologic therapies including major surgical resection and systemic therapy.

Patients presenting with gastric outlet obstruction may have dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Placement of a nasogastric (NG) tube, volume replacement (initially with normal saline), and correction of electrolyte imbalance is paramount.

Physical Findings

Most patients with early stage disease will have a normal physical examination. However, signs of malnutrition, cachexia, and jaundice should be sought. Patients with advanced stage disease may present with supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, abdominal mass, hepatomegaly, malignant ascites, or drop metastases in the cul-de-sac known as “Blumer’s shelf.” Presence of any of these physical findings suggest unresectability.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Laboratory Tests

A baseline hemoglobin will assess whether iron deficiency anemia is present. Patient’s renal function and hydration status should be assessed by measuring serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine in preparation for cross-sectional imaging. Evaluation and correction of abnormalities in electrolytes are important in patients with gastric outlet obstruction. Serum albumin and prealbumin are essential tools for assessing nutritional status.

Diagnostic Studies and Staging Evaluation

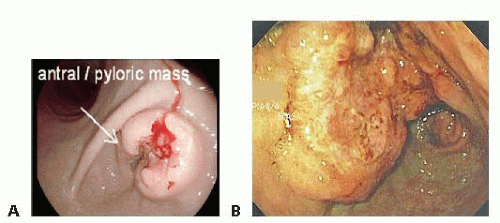

The evaluation of any upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptomatology begins with an upper GI endoscopy, especially if gastric cancer is suspected. Endoscopy provides histopathologic diagnosis as well as guidance toward the location and extent of the gastric tumor (FIG 1A,B). For example, the endoscopist needs to comment on the location of the tumor as well as the relationship to the first portion of the duodenum. Additionally, it is important to exclude the presence of linitis plastica by insufflating the stomach and evaluating its distensibility, as patients with linitis plastica carry a higher risk of metastatic disease and a median survival of approximately only 14 to 16 months.

Endoscopic ultrasound performed at the time of or subsequent to diagnostic endoscopy provides the most accurate estimation of the tumor depth (T stage) and needle biopsy of surrounding lymph nodes can be performed.3

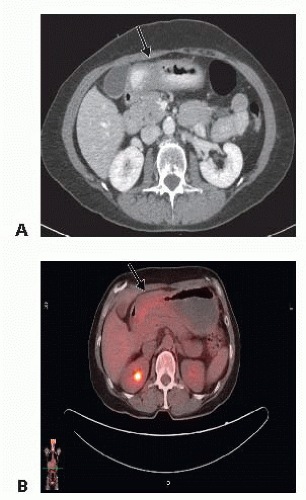

Pretherapy cross-sectional imaging (contrast computed tomography [CT] scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of abdomen and pelvis) is important to exclude distant metastatic disease to the liver or omentum (FIG 2A). In patients with proximal gastric cancer, the addition of chest crosssectional imaging is helpful to exclude the presence of metastases to the lung. The presence of bulky adenopathy adds prognostic value but should not preclude resection unless it is outside the area of resection, such as the periportal area or mesenteric vessels. Fewer than 15% of patients present with locally advanced disease extending to the pancreas. In these patients, we perform staging laparoscopy to exclude M1 disease and then recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan has evolved as a noninvasive radiographic staging modality to exclude the presence of metastatic disease (FIG 2B).

Staging laparoscopy: Due to the natural history of gastric cancer, up to a third of patients who have localized disease on staging evaluation have unsuspected hepatic and/or peritoneal disease.4 Thus, all patients should undergo staging laparoscopy to detect “subradiologic” disease. Staging laparoscopy is typically performed in a reverse TNM fashion. The operating surgeon should inspect the intraabdominal cavity for presence of peritoneal, omental, or hepatic metastases. The addition of peritoneal washing for cytology is an area of debate.5,6 It may have a place in patients at risk of undeclared metastatic disease or suboptimal performance status, as patients with positive peritoneal cytology have unfavorable overall prognosis.6 In the absence of concerning radiographic features, staging laparoscopy is typically performed at the time of the intended resection.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Margin-negative resection along with an adequate lymphadenectomy are the most critical components of the surgical resection.

Preoperative Planning

Addressing preoperative malnutrition: Gastric outlet obstruction caused by tumor as well as anorexia associated with malignancy contribute to malnutrition. As such, these patients may benefit from a placement of a preoperative nasojejunal tube and enteral nutrition. In patients presenting with malignant distal gastric obstruction, an endoscopic transpyloric stent may address the gastric outlet obstruction and thus help in optimizing the nutrition. Staging laparoscopy and placement of a feeding jejunostomy tube is another option.

Evaluation of the patient’s functional status: A careful review and optimization of underlying comorbidities (e.g., cardiac, pulmonary, diabetes) and performance status should be performed. A subset of high-risk individuals may benefit from preoperative admission to optimize the nutrition, electrolytes imbalance, and improve performance status (e.g., physical therapy) in preparation for the oncologic resection.

Preoperative antibiotics: Patients should have preoperative first- or second-generation cephalosporins prior to incision to reduce the risk of wound infection.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis: All patients should have a sequential compression device applied during the procedure. Use of subcutaneous heparin/low-molecularweight heparin is initiated on postoperative day 1 and continued throughout the hospitalization unless contraindicated.

Positioning

The patient is placed in supine position with both arms out at 90 degrees. Nipples to upper thigh should be prepped and draped in the operative field.

TECHNIQUES

STAGING LAPAROSCOPY

Pneumoperitoneum is created by either open technique or Veress needle. A 30-degree scope is inserted at the umbilicus. One to two additional 5-mm ports on left or right side of the abdomen are needed for additional visualization, grasping, and biopsy of suspicious tissue. A complete survey of the peritoneal cavity is performed, including undersurface of the diaphragm, liver surface, spleen, lining of peritoneal cavity, pelvis, small bowel surface, and omentum, for metastatic disease. If suspicious disease is observed, it is sent for frozen section. In the setting of biopsy-proven peritoneal disease, gastrectomy should not be considered and nonsurgical treatments should be initiated. However, selective palliative surgical procedures may be indicated, for example, in bleeding or obstructing cancers that cannot be palliated by endoscopic procedures. These decisions need to be individualized based on the performance status of the patient, extent of metastatic burden, and the projected survival.

If the staging laparoscopy is negative for peritoneal spread of the disease, operative resection is performed.

EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY

Abdomen is entered through a midline incision extending from the xiphoid process to just below the umbilicus. A bilateral subcostal incision, approximately 2 cm below the costal margin, also provides good exposure. During entry into the abdomen, the falciform ligament should be preserved as it can be used to buttress the duodenal closure.

A careful exploration of the peritoneal cavity is performed to exclude presence of subradiographic peritoneal or metastatic disease. The liver is carefully examined for any suspicious nodules.

MOBILIZATION OF THE GREATER CURVATURE OF THE STOMACH

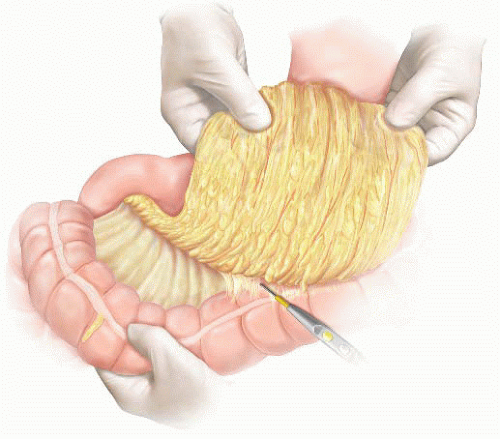

In this step, the transverse colon is separated from the greater omentum in an avascular plane (FIG 3). The stomach and the greater omentum are reflected superiorly, and the transverse colon is reflected inferiorly. The plane of fusion between the greater omentum and the transverse mesocolon is identified as a faint white line. This plane is incised with electrocautery to enter the lesser sac. This plane is advanced proximally and distally along the transverse colon.

The dissection proceeds to the proximal greater curvature of the stomach using either clamps and ties or an energy device, such as Harmonic™ or LigaSure™, to divide the short gastric vessels. When performing a subtotal gastrectomy, this dissection should stop at the beginning of the short gastric vessels as short gastric arteries provide the blood supply to the proximal gastric remnant.

DUODENAL MOBILIZATION AND TRANSECTION

The hepatic flexure of the colon is mobilized by dividing the avascular attachment of the right colon to the retroperitoneum. The separation of the greater omentum from the transverse mesocolon is continued to the hepatic flexure. This exposes the gastrocolic trunk, which is formed by the confluence of right gastroepiploic vein with a colonic vein and drains into the superior mesenteric vein (FIG 4). The right gastroepiploic vein is divided at its junction with the gastrocolic trunk. Alternatively, the gastrocolic trunk can be divided with a single fire of

vascular stapler. At this stage, the right gastroepiploic artery is divided at its origin at the infraduodenal level. The infrapyloric nodes, located adjacent to the origin of gastroduodenal artery, are mobilized with the specimen (FIG 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree