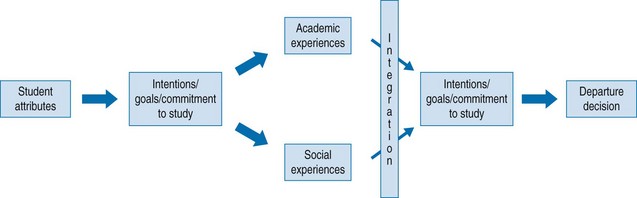

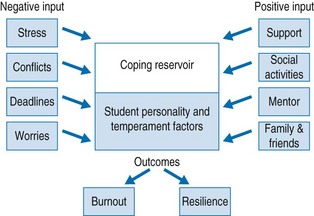

Chapter 44 Medical students are exposed to a variety of pressures, many of which may cause stress. Although this is true for all university students, medical students have higher anxiety scores than their non-medical peers (Buchman et al 1991, Sherry et al 1998). It seems that the first year of medical school is particularly stressful, with depression levels increasing significantly throughout that year (Stewart et al 1999). In later years, medical students frequently spend periods of time away from the university campus while studying in clinical placements elsewhere. This social isolation, compounded by unsocial hours of study, contributes to an ongoing cause of chronic stress (Schmitter et al 2008). Moffat and colleagues (2004) reported recent introduction of curriculum change as a further source of stress. Several studies have shown that the intense pressures and demands of medical school can have detrimental effects on the academic performance, physical health and psychological well-being of the student (Dyrbye et al 2006). Stress may also harm trainees’ professional effectiveness: it decreases attention, reduces concentration, impinges on decision-making skills, and reduces trainees’ abilities to establish strong physician–patient relationships (Dyrbye et al 2005). With regards to the physician–patient relationship, empathy declines during medical school and may even decline further during residency (Hojat et al 2004, Newton et al 2008, Toews et al 1997). It is worrisome that this decline of empathy, also called ‘ethical erosion’, seems to worsen when students’ activities are shifting towards patient care, as this is when empathy is most essential (Feudtner et al 1994). Associations between medical students’ stress, academic performance and personal and mental health underscore the importance of successful adaptation to the medical school environment, while maladaptive skills developed during medical school may lead to later professional maladjustment (Stern et al 1993). The inability to cope with the demands of medical school may lead to a cascade of consequences at both a personal and a professional level. Stress may affect trainees at all levels (students, interns, residents) with harmful outcomes such as alcohol and drug abuse, interpersonal relationship difficulties, depression, anxiety or even suicide (Dyrbye et al 2005). During their undergraduate years students are subjected to different kinds of stressors, such as the pressure of academic life with an obligation to succeed, an uncertain future and difficulties of integrating into the system (Robotham & Julian 2006). In addition, several factors peculiar to the medical profession have been found to contribute to a decline in students’ well-being as the years progress including exposure to patient suffering and deaths, sleep deprivation, financial concerns and workload (Davis et al 2001, Griffith & Wilson 2003, Hojat et al 2004, Woloschuk et al 2004). Problems and pressures experienced by students in general fall into six domains: 1. Personal: social, health, lack of time for recreation, relationships and family (Folse et al 1985) 2. Professional: coping with healthcare structures and life and death issues as seen in the working/learning environment, student abuse (verbal, emotional, etc.) (Silver & Glicken 1990) 3. Academic: course work, examinations (Kidson & Hornblow 1982), recent introduction of curriculum change 4. Administrative: anxiety relating to timetable and teaching venue changes or meeting curriculum deadlines 5. Financial: the ongoing problem of increasing student debt 6. Careers: choosing a specialty, application process, demands of residency (Gill et al 2001). Because students face such a wide range of potentially stressful factors, it is important to think of a stress-management system as an appropriate facility for all students to be aware of, a resource for maintaining academic performance, not just for helping students having problems. As stress is an aspect of a doctor’s professional life, it is important that all students develop coping skills as undergraduates (Stewart et al 1999). As Dyrbye put it: ‘Medical school should be a time of personal growth, fulfilment and well-being – despite its challenges’ (Dyrbye et al 2006). Based on epidemiological and observational studies quoted earlier, it is clear that this statement does not hold true for all medical students in all aspects or stages of their training. Negative experiences trigger different coping strategies amongst medical students. Those coping strategies – whether adaptive or maladaptive – can lead students either to express resilience and perseverance in their academic programme or to drop out. Students may arrive at the conclusion that the academic, social, emotional and/or financial costs of staying on are greater than the benefits (Tinto 1975), at which point they withdraw from academic or social integration (Yorke 1999). Tinto (1975, 1988) produced an integrative theory and model of student dropout. His model had six progressive phases: student pre-entry attributes, early goals/commitments to study, institutional experiences, integration into the institution, goals/commitments to the institution and ending in a departure decision (Fig. 44.1). Fig. 44.1 Simplified form of departure model. (Adapted from Tinto V: Stages of student departure: Reflections on the longitudinal character of student leaving, Journal of Higher Education 59:438–455, 1988.) This model described a longitudinal process of interactions between the individual and the academic and social systems of the university environment. It is against this background that we discuss possible ways of student support in this process and how to integrate them in medical schools. Dunn and colleagues (2008) developed a model of medical student coping which he termed the ‘coping reservoir’ (Fig. 44.2). Fig. 44.2 Conceptual model: Coping reserve tank. (Adapted from Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C: A conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout, Academic Psychiatry 32:44–53, 2008.) Students who have experienced academic or mental health problems before will deal with current concerns differently from those who have no history of academic problems, depression or anxiety. Those with no prior history will present with new onset anxiety. Students with a prior history have a relative additional risk in terms of lowered sense of confidence in own abilities, increased self-doubt on future goals (becoming a doctor) and recurrence of depressive/anxiety symptoms. Awareness of students’ prior mental health history is useful in recognition of normal reaction versus impending relapse in mood or anxiety disorder. However, issues of confidentiality and voluntary disclosure need to be considered by student counsellors (Chew-Graham et al 2003). Their support should be tailored to the individual student’s need. Parkes (1986) described three common methods of coping in student nurses in initial ward placements: general coping, direct coping and suppression. General coping refers to a tendency to use cognitive and behavioural coping strategies. Direct coping means using rational problem-orientated strategies to change or manage the situation and avoidance of emotionally based items such as fantasy, wishful thinking and hostility. By using suppression as the main coping strategy, students suppress thoughts of the situation and display behaviour that inhibits action, i.e. carrying on as if nothing has happened.

Student support

Introduction: Student well-being

Factors influencing student well-being

Role of medical teachers

Role of the student: Coping strategies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree