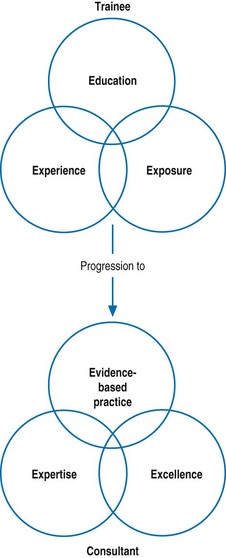

Chapter 4 UK medical and dental education has been regarded as one of the best systems in the world, but, with various changes recently, we have run into greater and greater difficulties. In 1996 the English Department of Health made a move to make postgraduate deans and regional advisers into civil servants and, later, NHS employees of the Strategic Health Authorities. This has led the Tooke Report to comment that ‘… the management and governance of the postgraduate deanery function in England is complex with little relationship to medical schools …’ (Tooke Report 2008). Strategic Health Authorities will be abolished in England in 2013, leaving the postgraduate deaneries with an uncertain future. Internationally, there are considerable variations in the number of recognized specialties and expert functions in medicine as well as in the organization, structure, content and requirements of postgraduate medical education. For example, the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, with its membership of 15 constituent professional colleges, offers postgraduate training in nearly 50 specialties (www.hkam.org.hk). The common curricular approach of all member colleges, of course, centres on the recognized clinical or practical placements, expert supervision, theoretical teaching, research experience, systematic assessments and evaluation of the training programmes. In the West Midlands, we studied the young pre-registration house officers and their consultant supervisors to see whether there were differences between how well prepared the pre-registration house officers felt they were and how well the consultants felt they were as a result of their undergraduate medical education. Both groups ranked communication skills areas highest (that is, best prepared) and ranked basic doctoring skills (such as prescribing, treatment, decision making and emergencies) lowest. House officers rated themselves significantly higher than did their consultant supervisors in 13 out of the 17 areas tested (Wall et al 2006). It is not surprising, therefore, that some doctors experience difficulties and may struggle to cope. As shown in Fig. 4.1, postgraduate medical training may be summarized as education, exposure and experience leading to expertise, evidence-based practice and excellence. Postgraduate medicine is a high-stakes education and practice. The ultimate goal in postgraduate medical education has to be that the trainees will, progressively, receive the appropriate clinical exposure to gain the necessary experience required in achieving expertise that allows them to provide a high standard of care in their respective fields. Another chief aim of postgraduate medical education is that the trainee eventually becomes the trainer and goes on to participate in the training of his or her juniors and medical students. The principles of adult learning and the process of structured educational training are both vital in postgraduate medical education with respect to the development of clinical and practical skills. In specialties related to surgery, acquisition of practical or operative skills requires additional attention (Patil et al 2003). The trainee is moving along the continuum from novice to expert, as described by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (2005). These five steps are as follows: Features of a postgraduate training include the following:

Postgraduate training

Introduction

The historical perspective in the UK

International perspective

Fundamentals of postgraduate medical education

Transition from medical student to doctor

Characteristics of postgraduate education

Standards for training

Nuts and bolts of the postgraduate curriculum

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Postgraduate training