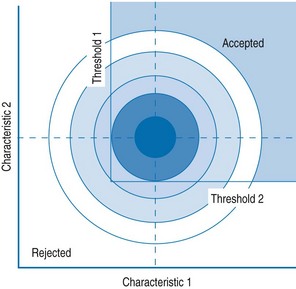

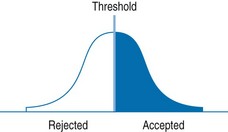

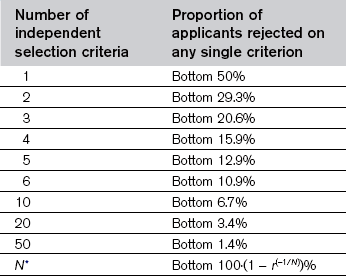

Chapter 43 • a vulnerable process legally and ethically • open to challenge on grounds such as discrimination • criticized by society at large • under-resourced given the implicit expectations of society, the profession and medical schools. The limits of selection are easily shown mathematically. If selecting on a single criterion (such as intellectual ability) which has a normal distribution of ability, and with a selection ratio of two applicants per place, the optimal selection is shown in Fig. 43.1. The candidates are placed in rank order, and those above the median are selected. Fig. 43.1 A simple model of selection when there is a single characteristic on which selection is taking place; those above the threshold are accepted, and those below are rejected. The limits of selection become apparent when two or more criteria are introduced, for example, intellectual ability and communication skills, which are essentially uncorrelated. The distribution is now bivariate normal (see Fig. 43.2) and the aim is to select the best 50% of candidates on the joint criteria. The dashed lines indicate the median for each of the separate distributions. Selecting candidates to be above a particular threshold on both criteria means they are in the top right-hand corner of the figure. The key point to realize is that the threshold on either criterion will be substantially below the median. In fact, with two independent criteria, selected candidates are only in the top 71% of the ability range, rather than the top 50%, and hence are less able on average than if either criterion on its own had been used. The same conclusion applies also if one allows compensation between the separate abilities (McManus & Vincent 1993). If medical student selection is based predominantly on academic achievement, then for nonacademic factors to be taken substantially into account, academic standards must be lowered. Medical schools considering nonacademic attributes for selection rapidly develop long lists of desiderata, often containing 5, 10, 20 or even 50 components. The model of Fig. 43.2 can easily be extended to three, four, five or many criteria, when the limits of selection appear with a vengeance. Assuming the criteria are statistically independent, then Table 43.1 shows that as the number of criteria rise, so the proportion of candidates eliminated on any single criterion (shown in the second column) becomes ever smaller. To put it bluntly, ‘if one selects on everything, one selects on nothing.’ Table 43.1 The effects of selection on the basis of multiple criteria (assuming two applicants for every place) *N: number of criteria; r: selection ratio (e.g. if r = 3, there are 3 applicants for each place and 1/3 applicants are accepted). Reproduced from McManus IC, Vincent CA: Selecting and educating safer doctors. In Vincent CA, Ennis M, Audley RJ, editors: Medical Accidents, Oxford, 1993, Oxford University Press, pp 80–105. • Selection should aim at a relatively small number of what can be called ‘canonical traits’ – the three or four stable characteristics that are likely to predict future professional behaviour and can be assessed reliably at medical school application. • If schools currently select almost entirely on academic ability, then they will have to reduce academic standards in order to select effectively on nonacademic criteria. • Selection should be recognized as being limited in its power. The really powerful tools for affecting change are education and training (McManus & Vincent 1993). Attempts have been made to identify canonical traits for selection (McManus & Vincent 1993). Doctors probably cannot be too intelligent. Meta-analyses of selection in many different occupations show that general mental ability is the best predictor both of job performance and of the ability to be trained (Schmidt & Hunter 1998). Although claims are often made for some minimum threshold ability level which is ‘good enough’, systematic research suggests that ‘more is better’ (Arneson et al 2011). Students study as university students for many different reasons, and those motivations mean they adopt particular study habits and learning styles. In Biggs’s typology (Table 43.2), both deep and strategic learning (but not surface learning) are compatible with the self-directed, self-motivated approach to learning that is required in the lifelong learning needed in medical practitioners. Table 43.2 Summary of the differences in motivation and study process of the surface, deep and strategic approaches to study Based on the work of Biggs 1987, 2003. Many studies have examined the ‘big five’ personality traits of extroversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Schmidt and Hunter’s (1998) meta-analysis showed that the best predictor of job performance and trainability, after intellectual ability, was integrity or conscientiousness, not least because highly conscientious people tend to work harder and be more efficient and so gain more and better experience. Conscientiousness may, though, not be a good predictor when creativity or innovation is important. At medical school, conscientiousness better predicts achievement in basic medical sciences, rather than clinical studies or postgraduate activities such as research output (McManus et al 2003).

Student selection

Introduction

Why select?

The limits of selection

What are the canonical traits in selection?

Intellectual ability

Learning style and motivation

Style

Motivation

Process

Surface

Completion of the course

Rote learning of facts and ideas

Focusing on task components in isolation

Fear of failure

Little real interest in content

Deep

Interest in the subject

Relation of ideas to evidence

Vocational relevance

Integration of material across courses

Personal understanding

Identification of general principles

Strategic/Achieving

Achieving high grades

Use of techniques that achieve

Being successful

highest grades

Personality

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine