Stromal Tissue and Extracellular Space

Diane C. Farhi

The stromal tissue of the bone marrow consists of adipose tissue, fibrous tissue, blood vessels, trabecular bone, and the extracellular space. The latter is a potential space among the hematopoietic and connective tissue elements, which becomes apparent in some important conditions of the bone marrow.

ADIPOSE TISSUE

Fat Necrosis

Fat necrosis of the bone marrow is a sign of pancreatic disease or, less commonly, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). In fat necrosis caused by pancreatitis, alcoholism is the most common underlying disorder. Histologic sections of the bone marrow show liquefactive necrosis of fat cells.

Serous Fat Atrophy

Serous fat atrophy refers to the shrinkage of fat cells and replacement by grainy or foamy material in the extracellular space (7, 8, 9, 10). Serous fat atrophy has been reported in anorexia nervosa, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and advanced carcinoma. The material consists of sulfated glycosaminoglycan. In practice, the term “serous fat atrophy” has been used interchangeably with “gelatinous transformation of the marrow,” which seems to have become the preferred term (see below).

Lipomembranous Polycystic Osteodysplasia

Lipomembranous polycystic osteodysplasia with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy (Nasu-Hakola disease) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder (11, 12, 13, 14, 15). It is caused by inactivating mutations in TYROBP, located on chromosome 19q13, and TREM2, located on chromosome 6p21, which encode signaling molecules in dendritic cells.

Patients present with dementia, basal ganglia calcification, and bone cysts with pathologic fractures.

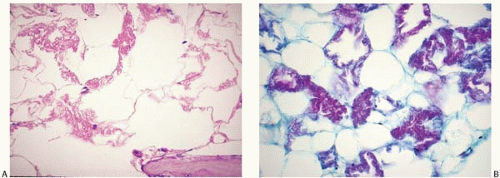

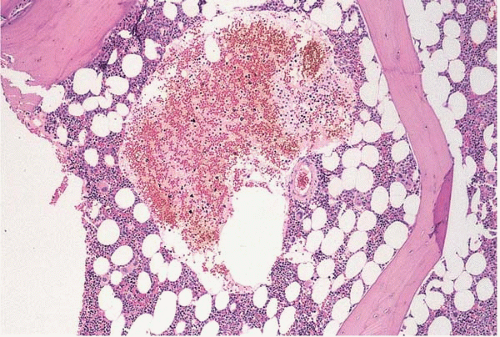

Histologic sections of the bone marrow show a peculiar change of the adipose tissue, which is transformed into lipid-filled cystic spaces surrounded by a convoluted hyaline membrane (Fig. 12.1).

FIBROUS TISSUE

Bone marrow fibrosis (myelofibrosis) may be constitutional or reactive, of known etiology or idiopathic. It is found in a wide variety of underlying conditions (Table 12.1 and Figs. 12.1, 12.2and 12.3). The term “marrow fibrosis” is used here to prevent confusion with primary myelofibrosis (chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis), a myeloproliferative neoplasm discussed in Chapter 21.

Constitutional Fibrosis

Constitutional (familial, hereditary) fibrosis has been reported in rare kindreds, in whom the disorder presents in early infancy and is typically fatal (16, 17, 18, 19). Marrow fibrosis is also found in gray platelet syndrome (20), trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) (21), and primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (pachydermoperiostosis) (22,23). Underlying genetic defects may also be responsible for some cases diagnosed as idiopathic childhood marrow fibrosis.

The differential diagnosis includes fibrosis associated with acquired myeloproliferative disorders and acute leukemia. These disorders may present from birth through infancy, and must be distinguished from constitutional syndromes occurring in the same age group.

Childhood Fibrosis

Infantile and childhood marrow fibrosis is rare and difficult to classify, and is often reported as an idiopathic or myeloproliferative neoplasm.

Such cases may be due to an underlying constitutional defect, autoimmune disorder, infectious disease, rickets, exposure to toxins or other injurious substances, and infantile myofibromatosis (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31). An autoimmune component seems present in idiopathic cases responding to immune modulators.

Some cases are related to, or may evolve into, acquired clonal disorders, including myeloproliferative neoplasms, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute leukemia, and Hodgkin lymphoma (29,32, 33, 34, 35, 36).

Idiopathic childhood marrow fibrosis should receive careful evaluation for potentially treatable underlying disorders and malignancy.

Reactive Fibrosis

Reactive marrow fibrosis is a common finding, which may be idiopathic or related to known triggering factors. It usually consists of fine reticulin fibers, less commonly of dense collagen. Monocytes and megakaryocytes are important in the genesis of marrow fibrosis, which is associated with increased marrow production of hyaluronan, megakaryocytic hyperplasia, and increased secretion or leakage of transforming growth factor-β and other cytokines (37, 38, 39, 40). Following are some of the conditions associated with marrow fibrosis.

TABLE 12.1 Conditions Associated with Marrow Fibrosis | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Autoimmune marrow fibrosis has been described as an independent entity and in association with numerous autoimmune conditions, including Hashimoto thyroiditis, hepatitis C infection, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, primary biliary cirrhosis, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and ulcerative colitis (38,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52).

Infectious diseases accompanied by marrow fibrosis include hepatitis C infection, paracoccidiomycosis, systemic leishmaniasis, and tuberculosis (53, 54, 55, 56). Fibrosis may also occur in the presence of hemophagocytic histiocytosis, or in any infection producing granulomatous inflammation.

Disorders of calcium and phosphate metabolism may be accompanied by marrow fibrosis (57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69). These include hypoparathyroidism, primary hyperparathyroidism, secondary hyperparathyroidism (renal osteodystrophy), rickets, and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.

The organic solvents benzene and toluene, which are toxic to the bone marrow, have been linked to marrow fibrosis (70,71)

Paget disease of bone may be accompanied by fibrosis (72).

Iatrogenic or therapy-induced marrow fibrosis has been reported in patients treated with fludarabine, thrombopoietin, interferon, interleukin-3, and radiotherapy, and in patients with graft-versus-host disease (73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78).

Many hematopoietic and lymphoid malignancies may be accompanied by fibrosis, including myeloproliferative neoplasms, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute leukemia of all types, B-cell neoplasms including Hodgkin lymphoma, T-cell neoplasms, and multiple myeloma. Of particular concern are the cases in which fibrosis is the presenting problem or the most obvious histologic finding, and may obscure the underlying diagnosis (79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90).

Metastatic malignancy in the marrow is often accompanied by fibrosis. Characteristically, breast and prostate carcinoma are found with prominent stromal changes that may obscure the underlying tumor.

The peripheral blood smear in cases of significant marrow fibrosis typically shows leukoerythroblastosis and may also show the effects of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (91,92). Bone marrow aspirate smears may be hypocellular due to a “dry tap” (93).

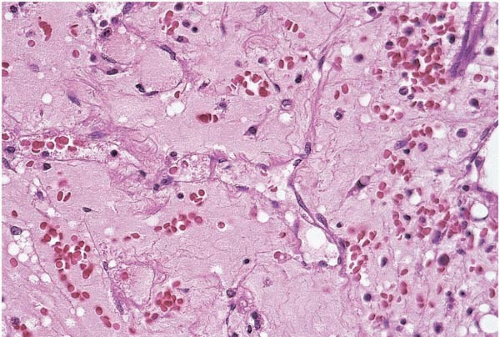

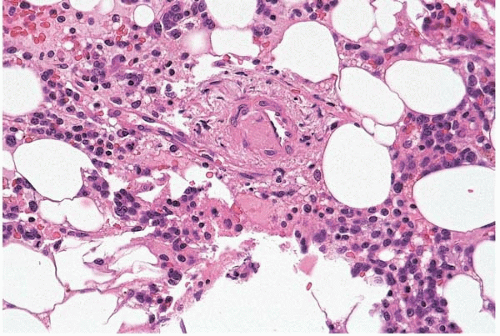

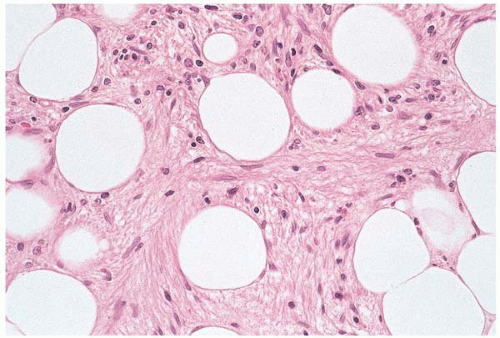

Histologic sections show a patchy to diffuse increase in reticulin fibers, which may be thickened and’or elongated (Fig. 12.2) (94). The presence of increased reticulin may be suspected in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections by a linear arrangement, or single filing, of hematopoietic cells. Close examination reveals the presence of delicate, eosinophilic strands between the aligned cells. A silver stain for reticulin is helpful and is often necessary to demonstrate increased reticulin in mild fibrosis. Marrow fibrosis is frequently accompanied by other stromal changes, especially osteosclerosis.

Figure 12.3 Dense fibrosis, bone marrow biopsy. Large areas of hematopoietic tissue are replaced by dense fibrous tissue in this specimen from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. |

Advanced fibrosis may be accompanied by collagen deposition, vascular proliferation, and osteosclerosis (Fig. 12.3). Fibrosis and osteosclerosis may be so extensive as to nearly obliterate the marrow cavity. In such cases, a careful search for underlying hematolymphoid or metastatic malignancy should be made.

The differential diagnosis includes reparative changes caused by a previous biopsy in the same site (95).

Fibrous Tumors

Invasive fibrous tumors may involve the bone marrow as a primary site or through intraosseous invasion of an adjacent tumor (96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102). These tumors may be histologically benign, dysplastic, or overtly malignant.

The differential diagnosis includes constitutional fibrosis and reactive fibrosis. Dysplastic and neoplastic fibrous tumors may be difficult to distinguish from these entities. The clinical presentation is helpful in arriving at the correct diagnosis.

BLOOD VESSELS

Reactive Vascular Lesions

Reactive vascular lesions of the bone marrow comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders, predominantly causing small vessel inflammation and thrombosis (103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115). Conditions associated with bone marrow vasculitis and thrombosis include giant cell arteritis, Churg-Strauss (allergic) angiitis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, Sjögren syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and ionizing radiation.

Figure 12.4 Sinusoidal dilation, bone marrow biopsy. A sinusoid is dilated almost beyond recognition in this specimen from a patient with treated acute myeloid leukemia. |

Other reactive vascular lesions rarely reported in the bone marrow include peliosis, bacillary angiomatosis, and the destructive lymphangiomatous proliferation associated with Gorham disease. Dilation and ectasia of bone marrow vessels, predominantly sinusoids, may be seen in acute hematopoietic tissue depletion.

The bone marrow shows proliferation, thrombosis, and’or dilatation of blood vessels, depending on the underlying disorder (Figs. 12.4, 12.5and 12.6). Serous fat atrophy and other changes may also be present.

The differential diagnosis includes hemangioma, Kaposi sarcoma, and hairy cell leukemia, which may produce vascular lesions in the bone marrow. Of these, the most difficult may be the distinction between bacillary angiomatosis and Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Vascular Tumors

Hemangiomas and lymphangiomas may be confined to the marrow space or involve the marrow together with adjacent tissues (116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122). These lesions usually affect the axial skeleton. Rarely, the bone marrow is involved as part of systemic hemangiomatosis (123,124). Kaposi sarcoma has been reported in the bone marrow (125,126).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree