11 Stress, depression and critical care

What is stress?

There is no definitive, accepted definition of stress. One definition (Lazarus 1998) is that stress is any influence that disturbs the natural balance of a person’s body or mind, including physical injury, disease, deprivation and emotional disturbance (Wingate & Wingate 1996). Anxiety (a state of apprehension) and worry (an over-anxious state of mind) are often the forerunners of both stressful and depressive states – in fact, the body has the same initial reaction as in the first stage of stress (see stress below). It can be due to:

a) a reaction to a potentially harmful situation; it is natural and healthy to experience anxiety when faced with danger or risk of some kind. Together with fear, it enables the body to deal with the situation by increasing the respiratory and heart rates, so that extra oxygen reaches the brain; it also releases energy and extra adrenaline (epinephrine) to help cope with the situation.

b) a reaction to an ongoing life event; here the anxious feeling or worry may be connected to work, a problematic marriage, illness, a son in the army who is sent into battle, etc. This sort of anxiety, if the situation becomes serious, usually develops into either stress or (and) depression, depending on the personality of the person.

Positive and negative stress

The production of adrenaline is one of the positive side effects of stress which is needed to motivate people and give the energy to do even the simplest of tasks. Stress is therefore not necessarily a problem – it only becomes one when we have more stress than we can cope with in the normal run of life; its depth is reflected by the rate of wear and tear in the body caused by life. In the introduction to his book on stress, Selye (1956) said that stress, like the emotions, can be labelled productive and unproductive, or positive and negative. A sportsperson experiences pleasurable, positive stress during a competitive game or when climbing Mount Everest. Positive stress stimulates us, giving us the energy to cope with challenging or demanding tasks, after which both body and mind return to their normal composure without any negative effect on health.

The relationship between stress and depression

When stress is chronic, it can be a cause of depression. Many depressive – and highly stressful – states are brought about by a severe life event (such as the death of a loved one) or a long-lasting bad situation (e.g. living with an incompatible partner) – in other words, a provoking factor; whether or not this turns to depression depends on the vulnerability of the person concerned and the number of difficulties arising together at any one time. In severe cases of stress and/or depression, mental exhaustion or fatigue can set in. Long-term stress can raise blood pressure and damage the body’s immune system, and it is linked to problems such as heart disorders, stomach ulcers and cancer. Highly stressed people are also more likely to have accidents (Haughton 1995 p. 6).

Table 11.1 Stressful life events

| Event | Score/100 |

|---|---|

| Death of spouse | 100 |

| Divorce | 73 |

| Separation | 65 |

| Jail term | 63 |

| Death of a close family member | 63 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 |

| Marriage | 50 |

| Fired from work | 47 |

| Marital reconciliation | 45 |

| Retirement | 45 |

| Change in health of a family member | 44 |

| Pregnancy | 40 |

| Sexual difficulties | 39 |

| Gaining a new family member | 39 |

| Business readjustment | 38 |

| Change in financial state | 38 |

| Death of a close friend | 37 |

| Change to a different line of work | 36 |

| Change in number of arguments with spouse | 35 |

| A large mortgage or loan | 30 |

| Foreclosure of a mortgage or loan | 30 |

| Change in responsibilities at work | 29 |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 29 |

| Trouble with in-laws | 29 |

| Outstanding persona achievement | 28 |

| Spouse begins or stops work | 26 |

| Beginning or end of school or college | 26 |

| Change in living conditions | 25 |

| Change in personal habits | 24 |

| Trouble with boss | 23 |

| Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | 20 |

| Change in school or college | 20 |

| Change in recreation | 19 |

| Change in church activities | 19 |

| Change in social activities | 18 |

| A moderate loan or mortgage | 17 |

| Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Change in the number of family gatherings | 15 |

| Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Holiday | 13 |

| Christmas | 12 |

| Minor violation of the law | 11 |

In the tradition of aromatherapy, specific essential oils are stress reducing, whereas others are energizing, and still others can have either effect, depending on the user’s state of mind/body interaction (Warren & Warrenburg 1993).

Response to stress

The body deals with all stress (positive or negative) by releasing extra energy from its nutritional ‘store’; at the same time, extra oxygen is transported to the brain and extra adrenaline produced. These changes prepare us to cope with the situation causing stress. There are three stages in the development of the body’s response to stress (Selye 1956):

1. The initial direct effect of the body exposed to a stressor, bringing about the alarm stage, where:

2. The second, resistant stage is the action taken using these extra resources, where the extra oxygen, energy and adrenaline act to enable the body to cope with the unacceptable situation. Lacking relief from the situation, the responses in stage 1 continue as the body tries to adapt and reach a balanced state. If the level of stress becomes chronic and continues without help, the body reaches the third stage.

3. With excess build-up of stress stage three commences and true (clinical) stress is experienced. This can occur because of an emotional disturbance like the above, severe physical injury, illness or work overload. There is exhaustion, resulting eventually in health problems. These may manifest as headaches, insomnia, digestive problems, skin disorders and susceptibility to infection owing to the gradual closing down of immune responses (Price & Price 2007 p. 252).

Table 11.2 Stress-associated problems

| Physical problems | Psychological problems | Social problems |

|---|---|---|

| Tiredness during the day | Vivid dreams | Increased arguments at home |

| Difficulty going to sleep | Lack of interest in the world | Tendency to avoid people |

| Frequent waking at night | Lack of motivation | Abuse of alcohol, tobacco or other drugs |

| Aches and pains | Listlessness | Increased aggression – particularly in young men |

| Increased number of infections | Irritability | Inappropriate behaviour |

| Palpitations | Tearfulness | Over-reaction to problems |

| High blood pressure | Anxiety | Ignoring problems |

| Heart attacks | Poor performance at work | Loss of libido |

| Stroke | Eating problems – too much or too little | |

| Diarrhoea | Poor self image | |

| Constipation | Lack of patience | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Depression | |

| Stomach cramps | ||

| Dental problems (often due to teeth grinding) | ||

| Mouth ulcers | ||

| Skin problems | ||

| Menstrual problems | ||

| Hormone imbalances |

Breakdown

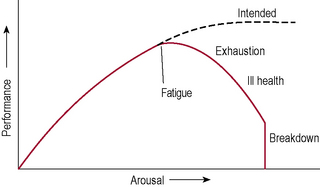

Figure 11.1 illustrates the relationship of stress to performance: when stress goes beyond a certain level, fatigue sets in and the performance level drops.

Modern life

O’Hanlon (1998) estimated that 40 million working days were lost each year in the UK as a result of stress; related problems account for more than six out of ten visits to doctors’ surgeries.

It is possible to suffer from an acute stress reaction:

Left untreated, stress can lead to self-destructive or harmful behaviour towards others. Stress-related disease is not only on the increase (Seaward 2000), but has a pathogenic effect on the immune function (Hori et al. 2003), appearing to exert an effect on the immune system similar to ageing (Hawkley & Capioppo 2004).

Fight or flight – good or bad?

Case study 11.1 Stress and depression

Intervention

Equal proportions of the following essential oils were selected for both prescriptions.

• Eucalyptus staigeriana [lemon-scented Eucalyptus] – antiseptic, calming

• Nepeta cataria [catnip] – anti-infectious (urinary). antiseptic, calming, neurotonic

• Citrus aurantium var. amara per (bitter orange) – antiseptic, calming, sedative

• Pinus sylvestris [pine] – antiseptic (particularly to the urinary system), uplifting, energizing.

When the threat is small, the response is small and can pass unnoticed among the many other distractions of a stressful situation. This mobilization of the body for survival has negative consequences: people are excitable, anxious and irritable, less able to work effectively, more accident prone and less able to make good decisions (http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article). The fight-or-flight response is discussed in Ch 7.

Dealing with stress

Advice commonly given for dealing with stress includes:

• healthy eating – vital to maintaining homoeostasis (fresh fruit and vegetables, complex carbohydrates combined, moderate amounts of protein-rich foods, some fats (in small amounts)

• rest and relaxation techniques, particularly those that focus on controlling the breathing

• aromas with or without massage help relaxation

• counselling or the more short-term cognitive behaviour therapy can change patterns of response and teach ways to deal with change.

Hospitalization

For many, hospitalization is the most stressful thing that could happen (Jamison, Parris & Maxon 1987). Patients lose their identity and become a number, exchanging their daily attire for nightwear and taking on a new role as a ‘condition’ in a bed (Buckle 1997 p. 165). However, despite being intimidated by the high-tech environment, the state of mind can be calmed by the use of essential oils (Mullen 2005 personal communication). Stress connected with hospitals is not confined to patients – they are tended by nurses and doctors who are also under stress.

Aromatherapists working in hospitals often have to treat the staff to help relieve the pressures they are under. Tysoe (2000) conducted a study to discover the effect on staff of essential oil vaporizers