ASKING THE RIGHT RESEARCH QUESTION

Whether one works in research and development (

R and D), marketing or another function of a company, asking the right question is the single most important aspect of conducting successful research. It is the starting point of the experimental process. If the research question is not well chosen

and phrased correctly, one is unlikely to be successful in designing the experiment correctly and in collecting the most appropriate data. It is possible to conduct studies well that will answer the wrong question or to conduct studies poorly or inadequately that are attempting to answer the right one. The time, staff effort, and money spent on pursuing the wrong question can be wasted, and especially for a small company, whose resources are limited, it might represent a major threat to its very survival.

Research questions can be posed in many different ways, including descriptive, normative, and cause and effect questions. It is usually important to model a research question as a hypothesis that can be tested. One way of achieving the best formulation of a question is to word it in several different ways and to discuss each with colleagues and/or others who are knowledgeable about the topic. Refine the question so that its meaning is clearly understood, and it completely describes the hypothesis to be tested. In clinical studies, this question is known as the objective of the study.

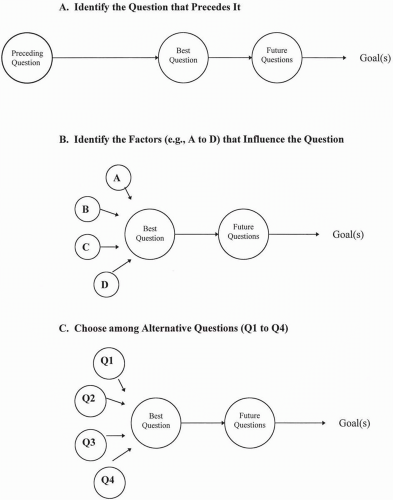

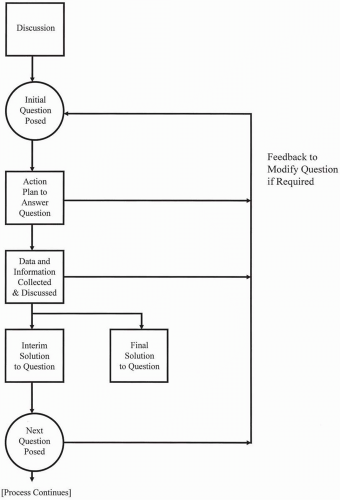

Once the research question is clearly and accurately posed, the most appropriate experimental design can be created. A few examples of such questions are given in

Table 15.1 and the procedures used to identify it and modify it are shown in

Figs. 15.2 and

15.3. This principle of asking the right question not only applies to every pharmaceutical function from marketing to production, but is also necessary to establish strategies, solve problems, and reach other decisions.

A clinical trial is designed to answer a clearly stated and detailed objective. This objective may be phrased as a question (e.g., does Drug A given for B weeks at dose C cause a change in parameter D of E% in Y number patients with disease G as compared with placebo?). Even determining the procedures to manufacture a new drug involves many questions. The initial question—Can we produce this drug ourselves?—rapidly leads to other questions such as:

Where could we manufacture it?

What would the cost be to manufacture it?

What would the consequences be at the plant for other products manufactured there?

Where else could it he manufactured, in what time frame and at what cost?

In turn, these questions progress to innumerable others. The design of a clinical trial, animal experiment or market research survey is totally dependent on the specific question(s) asked. The results obtained also are influenced by the precise question asked. To give an example of this point, a series of alternative questions that are similar and could be asked by a drug developer are briefly explored.

How to Decide if the Question Posed Is the Right One

There may be an appropriate time during a meeting to have the group discuss which question to specifically address and to wordsmith it until it meets everyone’s agreement. For example, one might say, “Now that we’ve decided to do X, what is the most appropriate question that follows this decision?” Alternatively, one might say, “Now that we’ve decided to do X, it seems that we should discuss question Y. Does everyone agree?”

If only one person is working on a project, it is always possible to consider this issue alone, although most questions serving as a basis for research of any type will require management’s approval. In some situations, a memo might be appropriate to present the proposed question.

When talking to colleagues, superiors or subordinates, one could say, “You know, we’ve spent a lot of time discussing the question or issue of X.” This could initiate a discussion about responses received so far or the next questions to ask. Identifying the right question to address is usually best done verbally and not in writing. It is an issue that often requires at least some discussion to ensure that all relevant people have agreed on the precise wording of the right question.

Prior to or during a discussion, the issue of identifying the question to address may be facilitated by drawing a flow diagram on a white board or on paper. For instance, one could say, “We are here and discussing this issue (or question) and the consequences that could result, but we could look at what issues (or questions) came before this.” Alternatively, at the end of a discussion, one could say, “We could look at the various influences on the proposed question.”

Refining Questions by Becoming Progressively More Targeted or Focused

The series of questions below illustrates how to progressively refine the specific question posed.

There are numerous other directions to take to refine and qualify the first question. Factors such as age of patient, prior treatment, concomitant treatment, or concurrent disease (e.g., liver failure, renal failure) are but a few of the issues that could be used to focus and refine this or other similar questions.

The importance of creating or choosing the best specific question should be apparent as a means to identify the most appropriate trial design and obtain the best data. If the objectives of a clinical trial are only expressed in general terms, then the trial design chosen may not be the most appropriate one to answer the true objectives.

Whose Perspective Should You Use?

When a project team of ten people representing ten different marketing (or ten production or ten

R and D) departments meet to discuss issues, plans and progress on a drug, each team member has a different perspective, and, therefore, provides a different viewpoint, of the drug. Their perspectives will differ even more if these people represent marketing, production and

R and D groups. This is appropriate and, by integrating and coordinating all of their perspectives, a unified whole approach, strategy and series of activities are created and implemented. When these activities are appropriately planned, implemented, and completed, it is a very satisfying experience for all participants.

When a senior pharmaceutical manager is dealing with some major problems there are often a variety of perspectives he or she could adopt, and yet some of these perspectives may be in conflict with each other. A simplistic question—What can we do about problem X?—means that the manager not only has to think of numerous audiences in many cases (e.g., shareholders, internal staff, public, board of directors), but that he or she may have to consider the impact of a variety of other perspectives as well (e.g., ethical, commercial, medical, regulatory, image). While some perspectives will lead to the same response, there are likely to be important differences and tradeoffs that must be considered. These issues are particularly important when there is no single “right” answer to the question at hand, either in the short term or in the long term. In dealing with the media, the person representing the company must assess how his or her own words may be changed or emphasized, as well as how various audiences will react to the comments.

Choosing among Related Marketing Questions of Interest

There are many types of questions that are posed when a company is trying to determine how to increase sales:

How can we increase our total revenues using any (and every) appropriate method?

How can we increase market share on our products (or on our bestselling products)?

How can we increase profits by manufacturing products more efficiently and by decreasing direct and indirect costs?

How can we use fewer staff to increase corporate profitability?

Which of the above questions would you ask if you wanted to increase sales? Some people would ask all of the above, plus many more questions to explore other areas and go into more depth on these questions. Others would focus on one or two areas they thought to be most appropriate. Perhaps a key question to pose before these is this: In which areas is it likely that we can increase profitability, and what techniques should we use?

But, no company can do everything to address the most global questions, and certainly not simultaneously. Someone (or a group) must decide which is the major question for the company now. If the question posed is extremely broad, the next level of questions to address must also be determined before anyone can start to plan the approach to obtain a specific answer.

Other possible questions to consider in this context are:

In which therapeutic area can we increase sales the most?

In which product line can we increase sales the most?

In which geographical area can we increase sales the most?

Will quality of life data improve sales on our leading drugs (or on our weakest drugs)?

What kind of data will have the greatest impact on sales?

Which of our products are the most vulnerable to competition?

Which of our products will lose proprietary protection first?

While a company may raise these and many other questions, some have to be addressed before others, and the effort spent addressing each question is likely to vary enormously. The general direction a company’s marketing group takes to build profits, and some of the specific approaches and strategies it adopts, will therefore depend on the questions it asks.

Asking the Wrong Question

There is a popular child’s game where one is asked to “identify what is wrong with this picture.” There may be a challenge to find a single error or many. The challenge may be simple or extremely difficult. This type of situation often occurs (unintentionally) at meetings or when reading reports when you are perplexed at what you are hearing or reading—and you realize that what is wrong is that the person (or group) is addressing the wrong question. This situation is often identified when realizing that the people discussing a topic are missing the point and they should be discussing something quite different (i.e., they are addressing the wrong question—or they are addressing an appropriate question but it is being addressed out of order).

The “wrong” question may merely be a case of asking the second or third question out of order. To focus on the second, third or other question before addressing and answering the first one (i.e., most relevant one to the situation) may lead a group to initiate actions that may be premature or inappropriate because the information from the first question was not yet obtained. The second (or other) question possibly did not need to be asked at all, needed to be asked in a different way or needed to be asked with knowledge of what the response was to the first question.

Examples where one may ask the right question in the wrong way include:

You go to outside consultants to answer a question rather than to qualified company staff who understand the issues in far greater detail than the consultants.

Having only one group provide an answer instead of approaching every group involved in the project (e.g., approaching the marketing or medical group, but not both groups)

Requiring your staff to provide an answer to an important question in two days, whereas a reasonable answer would require two weeks (or more) to prepare

On the other hand, in some situations one may allow six months for your staff to reach an answer to a question, whereas a reasonable answer could (and should) be made within six days.

Even when you identify the right question, if you ask the wrong person or group you may not get any answer, you may get the wrong answer or you may get an answer you do not believe is correct or appropriate. Alternatively, you may not realize the answer you receive is wrong or misleading. Therefore, having a competent person or group you trust address your question is essential.

The wrong question may be asked for many reasons, such as because the wrong frame of reference is being used, incomplete data are available, the person is naive or someone without a strong sense of logic is posing the question. There are also people who have dishonorable or selfish motives. Professional meetings sometimes go off on an unproductive tangent because of the wrong question being discussed.

One of the best ways to help move a group back on track without insulting anyone is to pose a question. One might ask: “Do we all agree that this question is the right one for us to address first?” It is also reasonable to say: “We have been addressing the question of ________, but it might also be useful to ask ________.” Alternatively, one might propose a more detailed question that, through qualifying statements, focuses the question more specifically on the issue that should be addressed.

Making Predictions Depends on the Questions Asked

While no one can predict the future with accuracy, some people or groups can come closer to guessing more accurately, and thus, make decisions that turn out to be better for the company. This skill is usually related to the quality of the questions they ask. Some groups ask poor questions and the (correct) information they receive leads them to derive erroneous conclusions. The most obvious error the author knows of came from a marketing research group that focused its business on predicting future areas of strong market activity. The group’s approach to making predictions was based on extrapolating past trends into the future. If a trend was exponentially increasing, it assumed the trend would continue and would be a red hot area on which to focus in the future. As a result, the group felt in 1990 that the best drug discovery areas to be conducting research in were:

Antisense

Wound healing

Antisepsis

Alzheimer’s disease

If the sales in a therapeutic area were declining, the area was described as a “dead area” and one to stay away from. If sales were flat, the area was predicted to remain flat (i.e., “plateaued”).

The most egregious error heard was the group’s prediction that the future for weight-reducing drugs was bleak. This was based entirely on flat sales for several years and no breakthrough drugs in development at the time. Some of the important points missed in making the predictions were that:

A single breakthrough drug can change flat sales curves overnight

Use of a new modality, such as a safe vaccine, could change a hot drug trend into a cold sales forecast

Red-hot pilot data in humans does not always yield red-hot Phase 3 data

Megatrends (e.g., growth of managed care, increased mergers among large pharmaceutical companies) influencing the future, as well as other relevant factors to consider (e.g., need for a safe drug in certain therapeutic areas), were ignored

Because the commercial potential of a safe weight-reducing drug is obviously so great, at least some enlightened companies would and are spending significant resources searching for a safe and effective treatment

Recognizing the Right Answer and Making a Decision

As the adage says, formulating the perfect question is only half the battle. Without the right answer, little information is available to guide thinking. How certain does a company want to be in the data it obtains before it is able to make a decision? Some companies make decisions when they only have about 60% of assurances, often to gain speed in the execution of their plans. Companies that are very conservative may require nearly 100% certainty to make a decision on the same question. The issue of how many people in a company have to ratify the decision before it is fully “signed off” has a large influence on how rapidly the company can implement its decisions.

The right answer almost always has to make sense. It may not be the answer one expected or hoped for, but it must be understood. Answers that are not understood should be distrusted. This often occurs when people use jargon or cannot respond clearly. While this occurs in every discipline, there are some fields in which the jargon and terms used are notorious for not being specific and objective. Thus, precise communication is often difficult for economists, statisticians, sociologists, or psychologists. It must be stressed that this consequence is often due to limitations in the science, rather than resulting from any desire of the professional not to communicate.

The right answer to a question may be simple or complex, but complex answers usually may be outlined and presented simply. Some answers must be verified by others or at least discussed with knowledgeable people who can comment with authority on the purported (or actual) answer.