Corporate Issues Regarding the Medical-Marketing Interface

To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers, may at first sight appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers; but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers.

–Adam Smith

The world of medical and marketing professionals may be viewed in various ways, including the various levels within each of their hierarchies and also how the two functions interact. This chapter and Chapter 94 place those two functions in a larger perspective, that of the entire corporation. Corporate issues that influence medical and marketing are discussed in this chapter, and organizational and staffing issues are discussed in the next chapter.

INTRODUCTION TO MEDICAL-MARKETING INTERACTIONS

There is a notorious chasm between medical and marketing staff in some pharmaceutical companies, whereas the staffs at other companies appear to coexist or even to interact on a fairly productive basis. What is the reason(s) for this difference, and what can companies and individuals do to improve the quality and often the amount of their interactions?

Individuals can do many things to help in this regard in their own interactions as well as in helping to catalyze their company to improve relationships between the two groups. One of the major prerequisites to achieve an optimal state of interactions is to understand the other person’s and group’s perspective and have at least a general knowledge of their activities and goals.

Most professionals have limited time to learn about the nature of the field of other professionals with whom they interact. While this section cannot provide that information, it seeks to provide an orientation to many of the issues and activities that relate to the medical-marketing interface.

The Marriage between Medical and Marketing Groups

There was a song in the 1950s called “Two Different Worlds.” That title characterizes the feelings of many people within clinical development and marketing about their two disciplines. Each group understands itself and its approaches but does not adequately understand or trust the other. In some cases, a feeling of wariness or even hostility develops between the two groups. Regardless of the current relationship between the two groups within a company, the relationship should be viewed as a marriage.

In the best marriages, the partners work together in relative harmony. However, marriages fall along a spectrum, and at the other extreme, a great deal of strife exists. A separation may result if each communicates coldly, is not honest with the other, acts alone without consulting the other, or has conflicting goals or maintains distance from the other. The secret of good relations between medical and marketing groups is to emulate the characteristics of a successful marriage: open, honest, frequent, and complete communication and an active desire to make the marriage work, ideally with shared goals. This can only exist when there is trust between the partners. It is best if the partners are also friends and not solely partners in a professional relationship. Unfortunately, the partners sometimes stay together solely because of their children (i.e., the drugs being developed and sold), and each partner would like a divorce. Although the activities within marketing and medical are generally well defined, many members of each group incorrectly believe that their activities can be conducted with minimal assistance from the other group. Although this analogy casts the medical and marketing groups as two individuals, each group is made up of many professionals who must interact in complex ways and with company staff from other disciplines as well. The principles guiding the relationship between medical and marketing disciplines also apply to two individuals from any groups who are working on the same product/project team.

External versus Internal Company Interactions

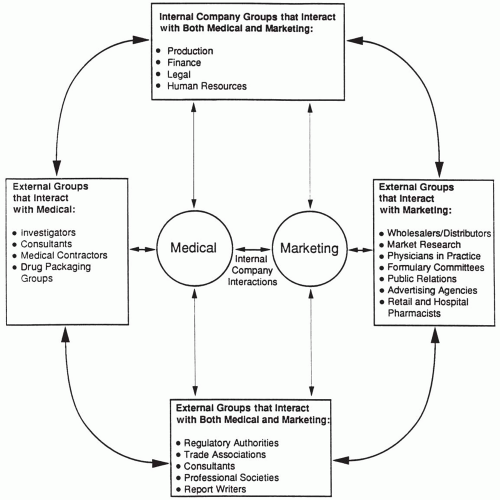

Medical and marketing employees interact with a wide variety of individuals and organizations that are external to the company. Thus, consideration of the interface between medical and marketing units must include external company interactions as well as internal ones. The marketing and medical staff interact with many of the same external groups, and even those that are different often have professional connections and relationships that close the circle (i.e., establish a connection among the groups). Thus, consideration of many external company interactions must also be included when discussing the medical-marketing interface within the pharmaceutical industry (Fig. 93-1).

CORPORATE PERSONALITY

Any professional with pharmaceutical company experience who spends even a few days at another company and talks with a number of staff can discern certain aspects of the other company’s personality (e.g., the attitudes of the staff and the style of management). It often takes longer to develop a feel about their traditions (e.g., specific activities and company history) unless one is taken to special events or places (e.g., a company museum).

The personality of a company may be manifest in such mundane aspects as follows:

Who parks where? Are reserved parking places respected?

Who eats where? Do senior managers eat separately from professional staff? Do professional staffs eat separately from workers?

What level of security is present at the outside gate (if one exists) and at the building?

How friendly are the staff one encounters who do not know you personally?

Do professionals seem generally happy with their jobs?

Do professionals seem generally happy to be working for the company?

Does the company appear to be particularly concerned about corporate secrecy?

What is the general atmosphere within and between different groups?

These aspects of a corporate personality, as well as many others, are often apparent to outsiders fairly quickly. Of course, the more interactions an appraisal is based on, the more likely it is to be accurate and complete. The corporate personality also is determined by which internal group has the greatest influence on the major decisions and directions of the company. Although any major group (e.g., production, finance, or marketing) could, in theory, fulfill this role, in practice, it is more likely to be marketing or research and development (R and D) than it is to be legal, production, or finance. This issue is discussed in the next section.

How Does a Drug’s Commercial Potential Influence a Drug’s Development?

The most obvious answer to this question is that commercial potential affects a drug’s priority and the amount of money that a pharmaceutical company is willing to spend on clinical trials. But a complete answer is much more complex and discussed in the next four parts of this section.

Regulatory Approaches to Drugs of High or Low Commercial Potential

Regulatory authorities worldwide have established generally high standards of what quantity and what quality of clinical data are sufficient to establish safety and effectiveness of a new drug. These standards are generally independent of a drug’s commercial value. The assumption here is that the disease being treated is not extremely rare because that does impact on the quantity and, sometimes, the quality of the clinical data that are appropriate and reasonable to collect (and sometimes limits what is possible to collect).

Clearly, commercial value is in the eye of the beholder and is influenced by many factors. A drug that is not valuable to a large company might be a “breakthrough” level drug to a small company. While the hurdle rates influence which drugs are developed, all drugs should be developed using appropriate regulatory standards.

Regulatory authorities do not state that, for a drug with minimal commercial potential, investigators may collect clinical data that are lower in quality or less in quantity than data for other drugs. In fact, the opposite is sometimes true. Sometimes, the regulatory authority requires more safety data on a new drug that will be the fifth or later drug of its type on the market (i.e., a “me-too”

drug) than were required for predecessors. The reasoning is that society already has four similar drugs available, and if the regulatory authorities are to allow a fifth one onto the market, it must be clearly shown to be as safe (and effective) as those already on the market.

drug) than were required for predecessors. The reasoning is that society already has four similar drugs available, and if the regulatory authorities are to allow a fifth one onto the market, it must be clearly shown to be as safe (and effective) as those already on the market.

Does a New Drug Have to Be Safer or More Effective Than Current Therapy?

If the new drug possesses a therapeutic advantage for a specific subpopulation of patients, then it may be approved for that particular group of patients. Some regulatory authorities used to impose a “needs clause” stating that all new drugs must demonstrate that they meet a therapeutic need to be considered for regulatory approval. Although this is not currently an official regulation in any developed country, it seems to lurk just below the surface, and a regulatory agency can prevent a drug from reaching the market that it does not believe provides “sufficient” benefit or “sufficient” safety, regardless of the clinical data that a company collects and submits.

Indeed, The Wall Street Journal online had an article titled “Our Lawless FDA” (Henderson and Hooper 2007) that said, “The FDA rejected Arcoxia (etoricoxib), a new Cox-2 inhibitor from Merck. The FDA explained that it didn’t see the need for another drug like this. Robert Meyer, director of the FDA‘s Office of Drug Evaluation II told reporters that ‘simply having another drug on the market’ wasn’t ‘sufficient reason to approve the product unless there was a unique role defined.’ The FDA is supposed to judge whether a drug is safe and efficacious and that’s all.” The Wall Street Journal is correct, and this statement by Robert Meyer is clearly against the regulations that state a drug will be approved if it is safe and effective.

Number of Patients to Enroll

The number of patients included in a clinical trial is established by statisticians applying scientific principles and is independent of a drug’s commercial potential. A trial for a drug with a high commercial value rarely will enroll fewer patients than required, and a trial for a drug with low commercial value rarely will enroll more patients than required. For example, the sponsor may enroll the fewest possible number of patients (i.e., use a low power) for a small commercial candidate drug and state that, for the drug to be developed further, it will have to demonstrate statistically significant efficacy in the smaller patient population (i.e., its therapeutic effect must be extremely high for it to be developed). The same reasoning will encourage a sponsor to include the largest number of patients reasonable in a clinical trial (i.e., use a high power) for a drug with high commercial value in order not to miss observing the effect, if it is truly present.

Design of a Clinical Trial

The design of a clinical trial should be chosen independently of a drug’s commercial value. For example, a new drug with low commercial potential may be studied in early Phase 2 trials using an open-label design. Typically, this leads to the finding that the drug is effective, and then several years and “large” sums of money are often spent to characterize the drug and collect clinical data. If a controlled trial follows and shows insufficient activity, the usual response of a company is to conduct another trial to confirm this result, rather than to terminate development. This occurred many times when companies were attempting to develop antidepressants, antipsychotics, and many other types of drugs using inadequately controlled trials.

A more scientifically appropriate approach is to conduct only double-blind trials throughout Phase 2, even if the early pilot trials are underpowered. It is a golden rule to collect excellent data on a relatively few patients as the basis for making a decision about whether to proceed further than to collect mediocre data on a large number of patients. The latter approach often leads to the wrong decision as to whether or not to proceed with a drug’s development. For example, a highly significant effect of a drug in an open-label, Phase 2 trial will encourage a company to pursue that drug’s development, particularly if an active control is also used in the trial. But these data are often misleading and can cause a sponsor to spend a lot of money over several or many years before the truth is unequivocally demonstrated. Pilot trials must be double blind, if at all possible, and should also be well controlled.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree