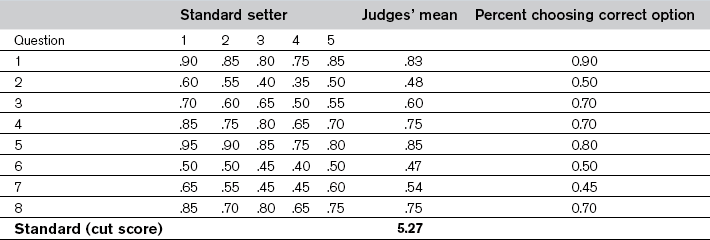

Chapter 36 Because standards are based on judgement, methods for selecting them are not intended to discover an underlying truth. Instead, they are a means for gathering a variety of perspectives, blending them together and expressing them as a single score on a particular assessment. Consequently, the methods do not differ in the correctness of the standards they yield, but in their credibility and defensibility. This chapter describes the types of standards, specifies the important characteristics of the standard setters and the methods, reviews some of the common methods for setting standards and provides a framework for evaluating their credibility (Norcini & Shea 1997, Norcini 2003, Norcini & Guille 2002). There are two types of standards: Relative standards are expressed in terms of the performance of a group of examinees. For instance, a relative standard may be that the 120 examinees with the highest scores are admitted to medical school. This type of standard is appropriate for assessments intended to select a certain number or percentage of examinees, such as tests for admissions or placement. There is a host of methods for setting standards, and many have variations. Reviews and descriptions are available elsewhere (Berk 1986, Cusimano 1996), but according to Livingston and Zieky (1982) they fall into four categories: • absolute methods based on judgements about assessment content (assessment-centred) • absolute methods based on judgements about individual examinees (examinee-centred) In Angoff’s method, the standard setters estimate the proportion of the borderline group that would respond correctly to an item. These are discussed with all being free to change their estimates, and the process is repeated for all items on the test. To calculate the standard, the estimates for each item are averaged and the averages are summed (see Table 36.1). Often, as a ‘reality check’, examinee performance is provided as well. In this example, the percentage of all examinees choosing the correct option (p value) is provided.

Standard setting

Introduction

Types of standards

Important characteristics of the standard setters and standard setting methods

Methods for setting standards

Absolute methods based on judgements about test questions (test-centred)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Standard setting