Chapter 72

Smoking Cessation

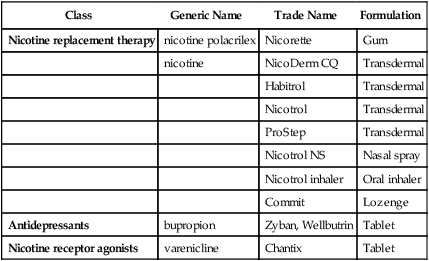

| Class | Generic Name | Trade Name | Formulation |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | nicotine polacrilex | Nicorette | Gum |

| nicotine | NicoDerm CQ | Transdermal | |

| Habitrol | Transdermal | ||

| Nicotrol | Transdermal | ||

| ProStep | Transdermal | ||

| Nicotrol NS | Nasal spray | ||

| Nicotrol inhaler | Oral inhaler | ||

| Commit | Lozenge | ||

| Antidepressants | bupropion | Zyban, Wellbutrin | Tablet |

| Nicotine receptor agonists | varenicline | Chantix | Tablet |

Many pharmacologic approaches have been used to help people stop smoking. In current use are the nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products and bupropion (Zyban, GlaxoSmithKline; Wellbutrin, GlaxoSmithKline). This chapter discusses methods for assisting the patient to stop smoking. The only drugs that are discussed in detail in this chapter are the NRT products because bupropion is discussed in Chapter 47. Many NRTs are now available OTC, but the patient still benefits from professional guidance on how to use these products.

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

• U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease, 2009. Available at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm.

Evidence-Based Recommendations

• The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products. Grade A recommendation.

• The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all pregnant women about tobacco use and provide augmented, pregnancy-tailored counseling for those who smoke. Grade A recommendation.

• Beneficial: Nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, antidepressants (bupropion or nortriptyline), not SSRIs

Cardinal Points of Treatment

• Brief advice on smoking cessation can be successful.

• Pharmacotherapy is recommended unless contraindicated.

• First line: Nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline

Nicotine replacement therapy does not improve relapse rate. Some patients will relapse regardless of whether they used nicotine replacement products with or without counseling. Table 72-1 lists actions and strategies for the primary care clinician from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) guidelines. Research from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys of 1991 through 1995 has documented that physicians reported counseling patients about smoking or prescribing nicotine replacement far less often than is called for by current practice guidelines, thus missing many opportunities to help their patients quit smoking.

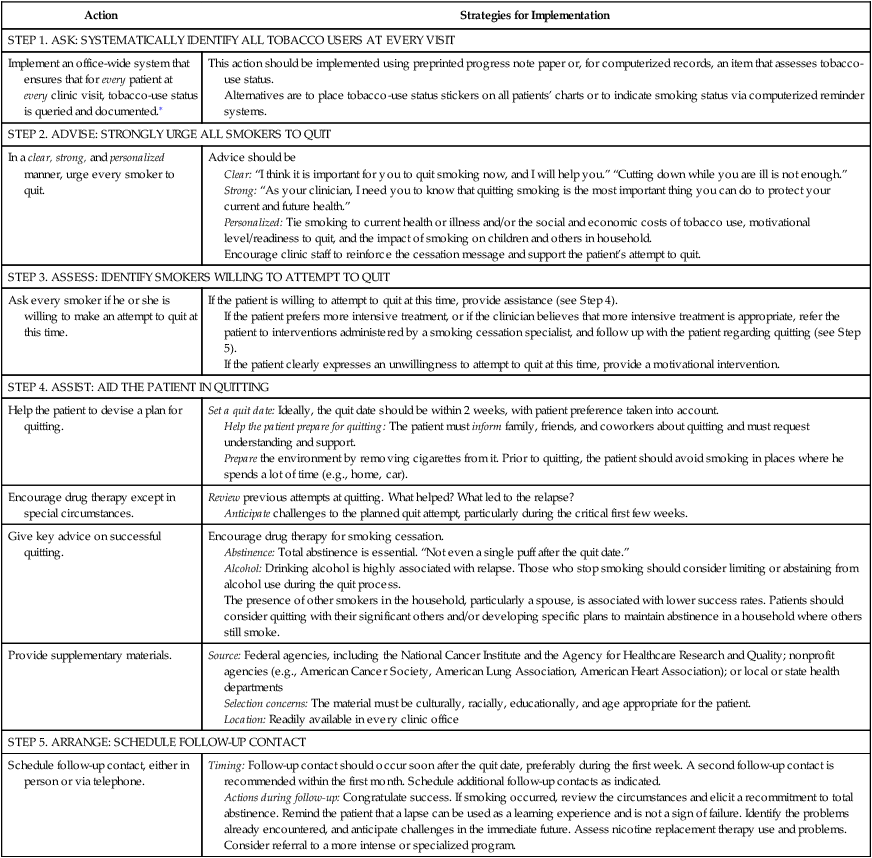

TABLE 72-1

Actions and Strategies for the Primary Care Clinician to Use in Smoking Cessation

| Action | Strategies for Implementation |

| STEP 1. ASK: SYSTEMATICALLY IDENTIFY ALL TOBACCO USERS AT EVERY VISIT | |

| Implement an office-wide system that ensures that for every patient at every clinic visit, tobacco-use status is queried and documented.∗ | This action should be implemented using preprinted progress note paper or, for computerized records, an item that assesses tobacco-use status. Alternatives are to place tobacco-use status stickers on all patients’ charts or to indicate smoking status via computerized reminder systems. |

| STEP 2. ADVISE: STRONGLY URGE ALL SMOKERS TO QUIT | |

| In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every smoker to quit. | Advice should be Clear: “I think it is important for you to quit smoking now, and I will help you.” “Cutting down while you are ill is not enough.” Strong: “As your clinician, I need you to know that quitting smoking is the most important thing you can do to protect your current and future health.” Personalized: Tie smoking to current health or illness and/or the social and economic costs of tobacco use, motivational level/readiness to quit, and the impact of smoking on children and others in household. Encourage clinic staff to reinforce the cessation message and support the patient’s attempt to quit. |

| STEP 3. ASSESS: IDENTIFY SMOKERS WILLING TO ATTEMPT TO QUIT | |

| Ask every smoker if he or she is willing to make an attempt to quit at this time. | If the patient is willing to attempt to quit at this time, provide assistance (see Step 4). If the patient prefers more intensive treatment, or if the clinician believes that more intensive treatment is appropriate, refer the patient to interventions administered by a smoking cessation specialist, and follow up with the patient regarding quitting (see Step 5). If the patient clearly expresses an unwillingness to attempt to quit at this time, provide a motivational intervention. |

| STEP 4. ASSIST: AID THE PATIENT IN QUITTING | |

| Help the patient to devise a plan for quitting. | Set a quit date: Ideally, the quit date should be within 2 weeks, with patient preference taken into account. Help the patient prepare for quitting: The patient must inform family, friends, and coworkers about quitting and must request understanding and support. Prepare the environment by removing cigarettes from it. Prior to quitting, the patient should avoid smoking in places where he spends a lot of time (e.g., home, car). |

| Encourage drug therapy except in special circumstances. | Review previous attempts at quitting. What helped? What led to the relapse? Anticipate challenges to the planned quit attempt, particularly during the critical first few weeks. |

| Give key advice on successful quitting. | Encourage drug therapy for smoking cessation. Abstinence: Total abstinence is essential. “Not even a single puff after the quit date.” Alcohol: Drinking alcohol is highly associated with relapse. Those who stop smoking should consider limiting or abstaining from alcohol use during the quit process. The presence of other smokers in the household, particularly a spouse, is associated with lower success rates. Patients should consider quitting with their significant others and/or developing specific plans to maintain abstinence in a household where others still smoke. |

| Provide supplementary materials. | Source: Federal agencies, including the National Cancer Institute and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; nonprofit agencies (e.g., American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, American Heart Association); or local or state health departments Selection concerns: The material must be culturally, racially, educationally, and age appropriate for the patient. Location: Readily available in every clinic office |

| STEP 5. ARRANGE: SCHEDULE FOLLOW-UP CONTACT | |

| Schedule follow-up contact, either in person or via telephone. | Timing: Follow-up contact should occur soon after the quit date, preferably during the first week. A second follow-up contact is recommended within the first month. Schedule additional follow-up contacts as indicated. Actions during follow-up: Congratulate success. If smoking occurred, review the circumstances and elicit a recommitment to total abstinence. Remind the patient that a lapse can be used as a learning experience and is not a sign of failure. Identify the problems already encountered, and anticipate challenges in the immediate future. Assess nicotine replacement therapy use and problems. Consider referral to a more intense or specialized program. |

∗Repeated assessment is not necessary in the case of the adult who has never smoked or has not smoked for many years, and for whom this information is clearly documented in the medical record.

From The Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline Panel and Staff: The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality smoking cessation clinical practice guideline, JAMA 275:1270, 1996.

Prevention and Early Intervention

Pharmacotherapy reduces the physical effects of nicotine withdrawal but does not address the psychologic aspects of smoking cessation. The highest rate of smoking cessation is seen in those individuals who are able to just stop smoking “cold turkey” and avoid replacement therapy. However, many are not able to do this. Pharmacotherapy should be used in conjunction with a behavioral modification program. Brief advice (i.e., 5 minutes) has been shown to be helpful. The five A’s model is recommended as a foundation for counseling (see Table 72-1). Also, a GETQUIT Support Plan is available to assist all patients who are taking varenicline.

Components of Smoking Cessation

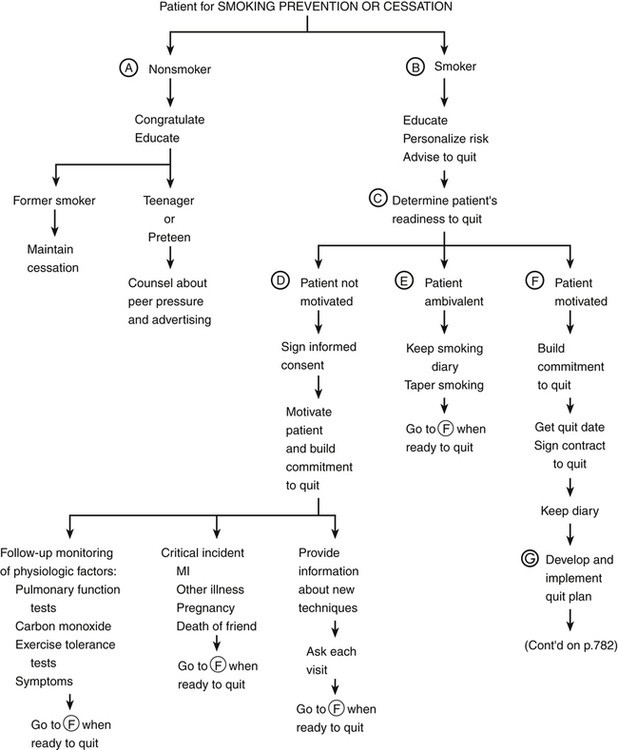

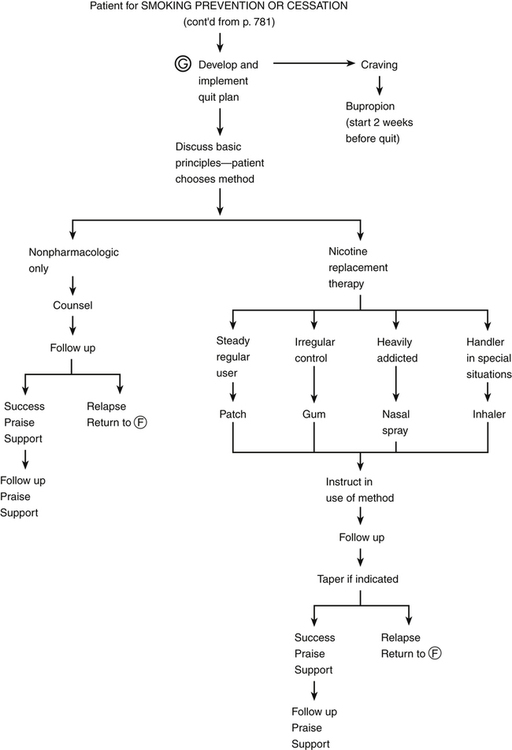

For all patients who do smoke, the provider should assess their willingness to attempt to quit (Figure 72-1). If they are unwilling or unready to quit, the provider should focus on motivational issues. The negative consequences of smoking also should be emphasized. Patients are not influenced often by remote events such as COPD or lung cancer but may be motivated by immediate effects such as fewer and milder respiratory infections or asthma. They may particularly respond to suggestions that they are hurting their family, particularly small or unborn children. Discuss the positive consequences of smoking cessation, such as saving money, tasting food better, and feeling better physically.

/>

/>

Pharmacologic Treatment

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree