Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Folliculitis, furuncles (boils), and carbuncles begin around hair follicles and are caused most often by Staphylococcus aureus. Folliculitis and small furuncles are generally treated with warm, moipruritic papules localizesdt heat to promote drainage; large furuncles and carbuncles require incision and drainage. A penicillinase-resistant penicillin such as dicloxacillin is commonly used for extensive or serious infections (e.g., fever). Empiric treatment of purulent infections that have a high suspicion for community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) should include clindamycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, a tetracycline, or linezolid.

Folliculitis, furuncles (boils), and carbuncles begin around hair follicles and are caused most often by Staphylococcus aureus. Folliculitis and small furuncles are generally treated with warm, moipruritic papules localizesdt heat to promote drainage; large furuncles and carbuncles require incision and drainage. A penicillinase-resistant penicillin such as dicloxacillin is commonly used for extensive or serious infections (e.g., fever). Empiric treatment of purulent infections that have a high suspicion for community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) should include clindamycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, a tetracycline, or linezolid.

![]() Erysipelas, a superficial skin infection with extensive lymphatic involvement, is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. The treatment of choice is penicillin, administered orally or parenterally, depending on the severity of the infection.

Erysipelas, a superficial skin infection with extensive lymphatic involvement, is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. The treatment of choice is penicillin, administered orally or parenterally, depending on the severity of the infection.

![]() Impetigo is a superficial skin infection that occurs most commonly in children. It is characterized by fluid-filled vesicles that develop rapidly into pus-filled blisters that rupture to form golden-yellow crusts. Effective therapy includes penicillinase-resistant penicillins (dicloxacillin), first-generation cephalosporins (cephalexin), and topical mupirocin. S. aureus is the primary cause of impetigo, with infections caused by CA-MRSA emerging in recent years.

Impetigo is a superficial skin infection that occurs most commonly in children. It is characterized by fluid-filled vesicles that develop rapidly into pus-filled blisters that rupture to form golden-yellow crusts. Effective therapy includes penicillinase-resistant penicillins (dicloxacillin), first-generation cephalosporins (cephalexin), and topical mupirocin. S. aureus is the primary cause of impetigo, with infections caused by CA-MRSA emerging in recent years.

![]() Lymphangitis, an infection of the subcutaneous lymphatic channels, is generally caused by S. pyogenes. Acute lymphangitis is characterized by the rapid development of fine, red, linear streaks extending from the initial infection site toward the regional lymph nodes, which are usually enlarged and tender. Penicillin is the drug of choice.

Lymphangitis, an infection of the subcutaneous lymphatic channels, is generally caused by S. pyogenes. Acute lymphangitis is characterized by the rapid development of fine, red, linear streaks extending from the initial infection site toward the regional lymph nodes, which are usually enlarged and tender. Penicillin is the drug of choice.

![]() Cellulitis is an infection of the epidermis, dermis, and superficial fascia most commonly caused by S. pyogenes and S. aureus. Lesions generally are hot, painful, and erythematous, with nonelevated, poorly defined margins. Oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocycline, or clindamycin is used for initial treatment of suspected CA-MRSA in patients with purulent cellulitis (i.e., lesion with purulent drainage or exudate, or nondrainable abscess). Treatment of nonpurulent cellulitis generally consists of a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (dicloxacillin) or first-generation cephalosporin (cephalexin) for 5 to 10 days, with the option of adding coverage for CA-MRSA in certain patients. Severe infections in hospitalized patients should receive empiric therapy with vancomycin.

Cellulitis is an infection of the epidermis, dermis, and superficial fascia most commonly caused by S. pyogenes and S. aureus. Lesions generally are hot, painful, and erythematous, with nonelevated, poorly defined margins. Oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, minocycline, or clindamycin is used for initial treatment of suspected CA-MRSA in patients with purulent cellulitis (i.e., lesion with purulent drainage or exudate, or nondrainable abscess). Treatment of nonpurulent cellulitis generally consists of a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (dicloxacillin) or first-generation cephalosporin (cephalexin) for 5 to 10 days, with the option of adding coverage for CA-MRSA in certain patients. Severe infections in hospitalized patients should receive empiric therapy with vancomycin.

![]() Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but life-threatening infection of subcutaneous tissue that results in progressive destruction of superficial fascia and subcutaneous fat. Early and aggressive surgical debridement is an essential part of therapy for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Mixed infections are treated with broad-spectrum regimens that cover streptococci, gram-negative aerobes, and anaerobes. Infections caused by S. pyogenes or Clostridium species should be treated with the combination of penicillin and clindamycin.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but life-threatening infection of subcutaneous tissue that results in progressive destruction of superficial fascia and subcutaneous fat. Early and aggressive surgical debridement is an essential part of therapy for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Mixed infections are treated with broad-spectrum regimens that cover streptococci, gram-negative aerobes, and anaerobes. Infections caused by S. pyogenes or Clostridium species should be treated with the combination of penicillin and clindamycin.

![]() Diabetic foot infections are managed with a comprehensive treatment approach that includes both proper wound care and antimicrobial therapy. Potential pathogens include staphylococci, streptococci, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and obligate anaerobes. Antimicrobial regimens for diabetic foot infections are based on severity of the infection, expected treatment setting, and risk factors for infection with more resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Outpatient therapy with oral antimicrobials should be used whenever possible for less severe infections, while more severe infections initially require IV therapy.

Diabetic foot infections are managed with a comprehensive treatment approach that includes both proper wound care and antimicrobial therapy. Potential pathogens include staphylococci, streptococci, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and obligate anaerobes. Antimicrobial regimens for diabetic foot infections are based on severity of the infection, expected treatment setting, and risk factors for infection with more resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Outpatient therapy with oral antimicrobials should be used whenever possible for less severe infections, while more severe infections initially require IV therapy.

![]() Prevention is the single most important aspect in the management of pressure sores. After a sore develops, successful local care includes a comprehensive approach consisting of relief of pressure, proper cleaning (debridement), disinfection, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy if an infection is present. Good wound care is crucial to successful management.

Prevention is the single most important aspect in the management of pressure sores. After a sore develops, successful local care includes a comprehensive approach consisting of relief of pressure, proper cleaning (debridement), disinfection, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy if an infection is present. Good wound care is crucial to successful management.

![]() All bite wounds (either animal or human) should be irrigated thoroughly with large volumes of sterile normal saline, and the injured area should be immobilized and elevated. Depending on the severity of the bite wound, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid or ampicillin–sulbactam is often used for treatment of animal bites because of their coverage of Pasteurella species, streptococci, S. aureus, and anaerobes typically present in the oral flora of dogs and cats.

All bite wounds (either animal or human) should be irrigated thoroughly with large volumes of sterile normal saline, and the injured area should be immobilized and elevated. Depending on the severity of the bite wound, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid or ampicillin–sulbactam is often used for treatment of animal bites because of their coverage of Pasteurella species, streptococci, S. aureus, and anaerobes typically present in the oral flora of dogs and cats.

![]() Although antimicrobial prophylaxis of dog bites is not recommended routinely, patients with bite injuries caused by cats or humans should be given prophylactic antimicrobial therapy for 3 to 5 days. Infected bite wounds should be treated for 7 to 14 days with oral or IV antibiotics having activity against Eikenella corrodens, streptococci, S. aureus, and β-lactamase–producing anaerobes.

Although antimicrobial prophylaxis of dog bites is not recommended routinely, patients with bite injuries caused by cats or humans should be given prophylactic antimicrobial therapy for 3 to 5 days. Infected bite wounds should be treated for 7 to 14 days with oral or IV antibiotics having activity against Eikenella corrodens, streptococci, S. aureus, and β-lactamase–producing anaerobes.

Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) may involve any or all layers of the skin (epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous fat), fascia, and muscle. They also may spread far from the initial site of infection and lead to more severe complications, such as endocarditis, gram-negative sepsis, or streptococcal glomerulonephritis. Sometimes the treatment of SSTIs may necessitate both medical and surgical management. This chapter presents details of the pathogenesis and management of some of the most common infections involving the skin and soft tissues, ranging in severity from superficial to life-threatening.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Bacterial infections of the skin can be classified as primary or secondary (Table 88–1).1–3 Primary bacterial infections usually involve areas of previously healthy skin and are caused by a single pathogen. In contrast, secondary infections occur in areas of previously damaged skin and are frequently polymicrobic. SSTIs are also classified as complicated or uncomplicated. Complicated infections are those that involve deeper skin structures (e.g., fascia, muscle layers), require significant surgical intervention, or occur in patients with compromised immune function (e.g., diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection).4 Other categories that are crucial for successful treatment are the differentiation of necrotizing versus nonnecrotizing, as well as purulent versus nonpurulent, SSTIs.4–7

SSTIs are among the most common infections seen in community and hospital settings.8,9 However, most infections are believed to be mild and are treated in an outpatient setting, making it difficult to accurately quantify community-acquired SSTIs. SSTIs were diagnosed in 0.8% of physician office visits between 1993 and 2005; this corresponded to approximately 82 million diagnoses of SSTI, being more common among 70 years of age and older.3 Emergency room visits for SSTIs have increased dramatically in recent years, attributed primarily to an increase in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) cellulitis and abscesses.10,11 A study of emergency department visit rates between 1997 and 2007 found a 3.1-fold increase (11% per year) for abscess SSTIs, with only a minimal increase in nonabscess SSTIs.11 According to an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report, in 2007 SSTIs were responsible for over 600,000 hospitalizations and represented 2% of all admissions in males and 1.2% in females.9 Another study examined the rate and occurrence of infectious disease hospitalization using data from the Nationwide Input Sample for 1998 to 2006.12 A total of 10.1% of hospitalizations during that period were due to cellulitis.

While the exact incidence of SSTIs is unknown, the frequency of infections caused by drug-resistant gram-positive cocci has been increasing.4–7 While the high incidence of healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) has been a major concern for many years,13 the emergence of CA-MRSA is even more problematic.5–7,13–19 CA-MRSA are characteristically isolated from patients lacking typical risk factors (e.g., prior hospitalization, long-term care facility) and are often susceptible to non–β-lactam antibiotics such as trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin.1,13,14,16,18,20 They also differ genetically from HA-MRSA with methicillin resistance carried on the type IV staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec (SCCmec) element of the mecA gene.1,13 CA-MRSA strains often harbor genes for Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a cytotoxin responsible for leukocyte destruction and tissue necrosis. In contrast, HA-MRSA strains usually lack genes for PVL and are associated with SCCmec alleles I to III.1,13,16,16,19 While the incidence of HA-MRSA has declined in recent years,21 the incidence of CA-MRSA has dramatically increased.4–7,20 Clinicians should suspect CA-MRSA in geographic areas with a high prevalence of these strains, or in recurrent or persistent infections that are not responding to appropriate β-lactam therapy. Concerns for the future are the mixing of community and nosocomial strains, with HA-MRSA strains acquiring virulence genes (PVL) or CA-MRSA strains acquiring antimicrobial resistance via the SCCmec element.13

In addition to the emergence of CA-MRSA, treatment choices for SSTIs have been further complicated by the increased incidence of macrolide-resistant strains of S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.16,20,22 Data from the Minnesota Department of Health found erythromycin susceptibility among CA-MRSA strains decreased from 45% to 13% during the years 2000 to 2005.20 There is concern about the use of clindamycin for CA-MRSA infections due to the risk of inducible clindamycin resistance in S. aureus strains that are erythromycin-resistant, but clindamycin-susceptible.20 A double-disk test (D-zone test) is recommended to identify erythromycin-resistant strains with inducible clindamycin resistance if treatment with clindamycin is desired.6,7,13,23 A positive D-zone test, indicating the presence of the erm gene, suggests the possibility of the emergence of clindamycin resistance during therapy.13

ETIOLOGY

The majority of SSTIs are caused by gram-positive organisms present on the skin surface.7,24 Gram-positive bacteria (coagulase-negative staphylococci, diphtheroids) are the predominant flora of the skin, with gram-negative organisms being relatively uncommon (Table 88–2).1–3 S. aureus, as well as a variety of gram-negative bacteria, including Acinetobacter species, can be found in moist intertriginous areas (e.g., axilla, groin, and toe webs) of the body.1,2,25 Approximately 30% to 35% of healthy individuals are reported to be colonized with S. aureus on the skin or in the anterior nares.1,3 Colonization, whether transient or permanent, provides a nidus for infection should the integrity of the epidermis be compromised.1,2,10

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

S. aureus and S. pyogenes account for the majority of community-acquired SSTIs.1,10,24 Data from large surveillance studies showed S. aureus to be the most common cause (45%) of SSTIs in hospitalized patients.26 Also of note in these studies was the 36% incidence of methicillin resistance among strains of S. aureus. Other common nosocomial pathogens included Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11%), enterococci (9%), and Escherichia coli (7%).26

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The skin serves as a barrier between humans and their environment, therefore functioning as a primary defense mechanism against infections. The skin and subcutaneous tissues normally are extremely resistant to infection but may become susceptible under certain conditions. Even when high concentrations of bacteria are applied topically or injected into the soft tissue, resulting infections are rare.1–3,27,28 Several host factors act together to confer protection against skin infections. Because the surface of the skin is relatively dry and has a pH of approximately 5.6, it is not conducive to bacterial growth.1,3 Continuous renewal of the epidermal layer results in the shedding of keratocytes, as well as skin bacteria.2 In addition, sebaceous secretions are hydrolyzed to form free fatty acids that strongly inhibit the growth of many bacteria and fungi. Conditions that may predispose a patient to the development of skin infections include (a) high concentrations of bacteria (>105 microorganisms), (b) excessive moisture of the skin, (c) inadequate blood supply, (d) availability of bacterial nutrients, and (e) damage to the corneal layer allowing for bacterial penetration.2,3,27,28

The best defense against SSTI is intact skin.2,27 The majority of SSTIs result from the disruption of normal host defenses by processes such as skin puncture, abrasion, or underlying diseases (e.g., diabetes).1,2,27,29 The nature and severity of the infection depend on both the type of microorganism present and the site of innoculation.

FOLLICULITIS, FURUNCLES, AND CARBUNCLES

![]() Folliculitis is inflammation of the hair follicle and is caused by physical injury, chemical irritation, or infection. Infection occurring at the base of the eyelid is referred to as a stye. While folliculitis is a superficial infection with pus present only in the epidermis,10,24 furuncles and carbuncles occur when a follicular infection extends from around the hair shaft to involve deeper areas (subcutaneous tissue) of the skin.29 A furuncle, commonly known as an abscess or boil, is a walled-off mass of purulent material arising from a hair follicle.10 The lesions are called carbuncles when adjacent furuncles coalesce to form a single inflamed area.10 This aggregate of infected hair follicles forms deep masses that generally open and drain through multiple sinus tracts.13,29 S. aureus is the most common cause of folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles.13,29 Inadequate chlorine levels in whirlpools, hot tubs, and swimming pools have been responsible for outbreaks of folliculitis caused by P. aeruginosa.1,29 Outbreaks of furunculosis caused by S. aureus and CA-MRSA have been reported in settings involving close contact (e.g., families, prisons), especially when skin injury was common (such as with sports).13,29 In addition, some individuals experience repeated episodes of furunculosis.24 The major predisposing factor in recurrent infection is the presence of S. aureus in the anterior nares.16,24,29

Folliculitis is inflammation of the hair follicle and is caused by physical injury, chemical irritation, or infection. Infection occurring at the base of the eyelid is referred to as a stye. While folliculitis is a superficial infection with pus present only in the epidermis,10,24 furuncles and carbuncles occur when a follicular infection extends from around the hair shaft to involve deeper areas (subcutaneous tissue) of the skin.29 A furuncle, commonly known as an abscess or boil, is a walled-off mass of purulent material arising from a hair follicle.10 The lesions are called carbuncles when adjacent furuncles coalesce to form a single inflamed area.10 This aggregate of infected hair follicles forms deep masses that generally open and drain through multiple sinus tracts.13,29 S. aureus is the most common cause of folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles.13,29 Inadequate chlorine levels in whirlpools, hot tubs, and swimming pools have been responsible for outbreaks of folliculitis caused by P. aeruginosa.1,29 Outbreaks of furunculosis caused by S. aureus and CA-MRSA have been reported in settings involving close contact (e.g., families, prisons), especially when skin injury was common (such as with sports).13,29 In addition, some individuals experience repeated episodes of furunculosis.24 The major predisposing factor in recurrent infection is the presence of S. aureus in the anterior nares.16,24,29

TREATMENT

Folliculitis, Furuncles, and Carbuncles

Desired Outcomes

The goals of treatment include relieving discomfort, preventing further spread of the infection, and preventing recurrence. Controlling recurrent furunculosis is key due to the difficulty in treating chronic furunculosis.24 Treatments should be effective and inexpensive and have minimal adverse effects.

Treatment

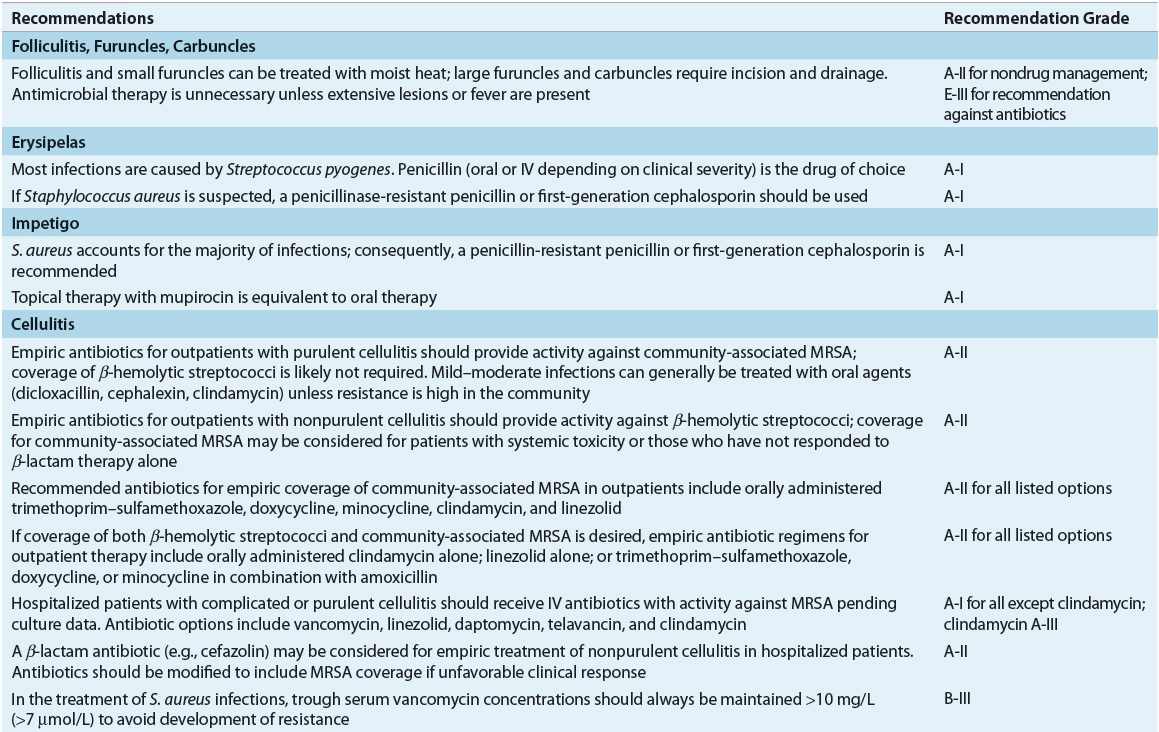

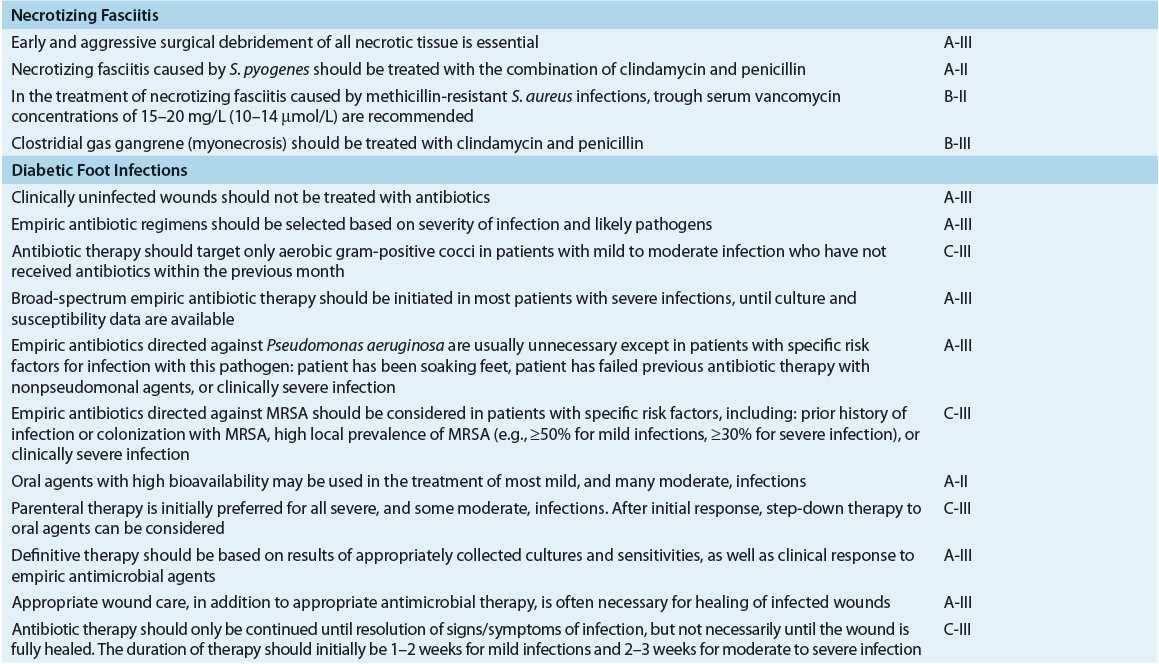

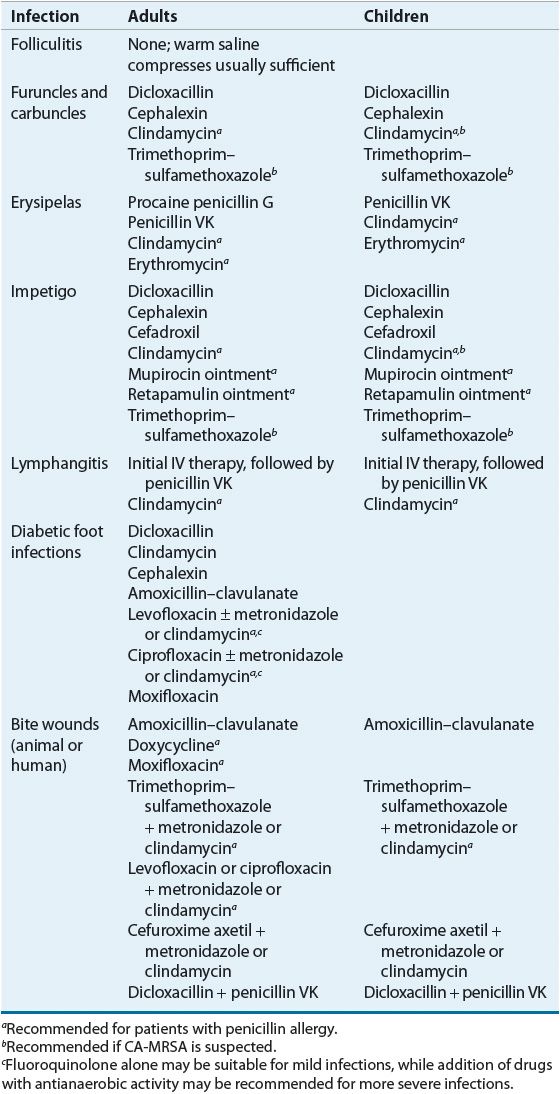

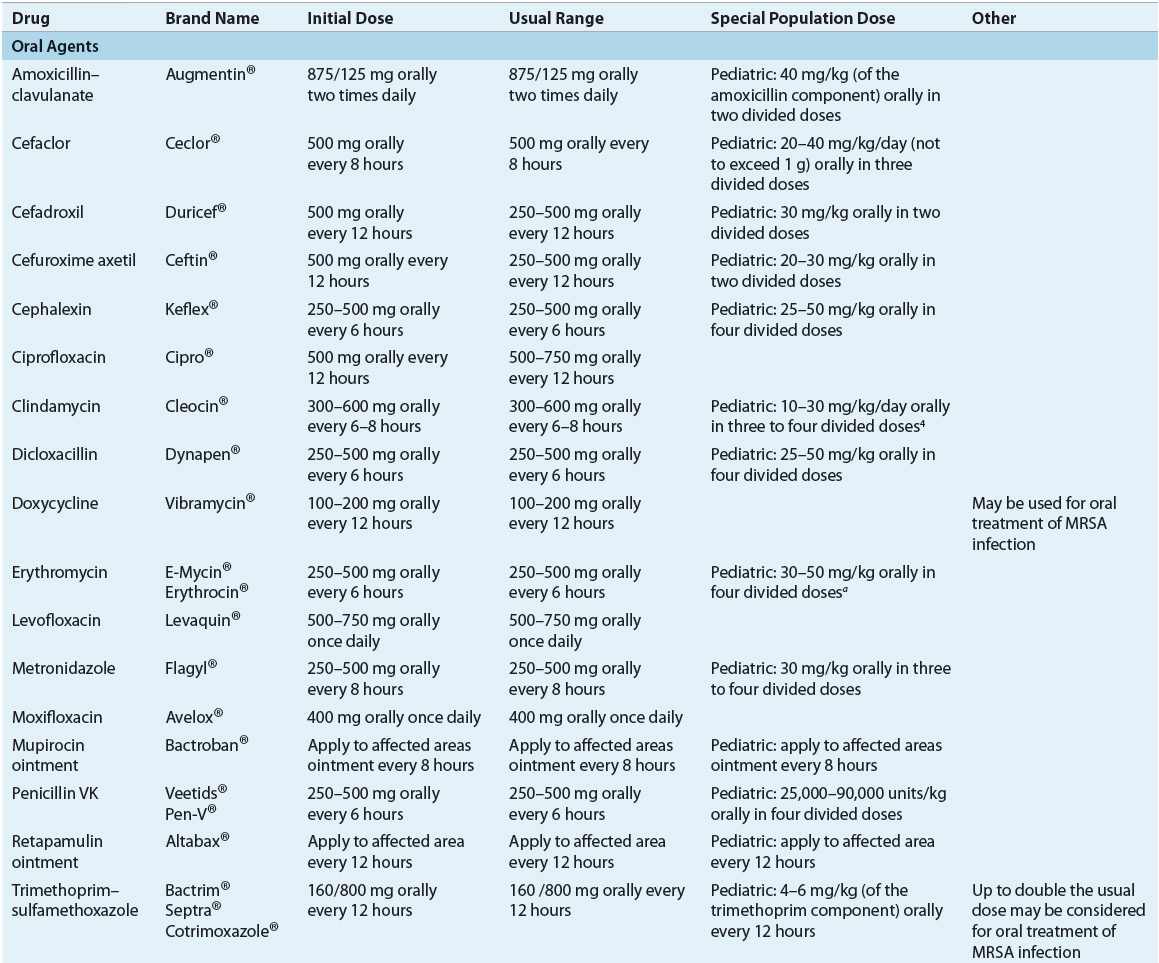

Table 88–3 summarizes evidence-based treatment recommendations from clinical guidelines for SSTIs.5,6,16,30–33 Treatment of folliculitis generally requires only local measures, such as warm moist compresses or topical therapy (e.g., clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, or benzoyl peroxide).29,31 Topical agents generally are applied two to four times daily for 7 days. Small furuncles generally can be treated with moist heat, which promotes localization and drainage of pus.29,31 Large and/or multiple furuncles and carbuncles require incision and drainage.4,13,16,31,32 Systemic antibiotics are usually not necessary unless accompanied by fever or extensive cellulitis.4,16 Treatment of more severe infections generally consists of a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (such as dicloxacillin) or a first-generation cephalosporin (such as cephalexin) for 5 to 10 days (refer to Table 88–4 for adult and pediatric doses). An alternative agent for penicillin-allergic patients is clindamycin. Empiric treatment of purulent infections that have a higher suspicion for CA-MRSA should include clindamycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, a tetracycline, or linezolid.4,6,24,32 For individuals with nasal colonization, application of mupirocin ointment twice daily in the anterior nares for the first 5 days of each month decreases recurrent furunculosis by almost half.16,24 In addition, a single oral daily dose of clindamycin 150 mg for 3 months or 500 mg of azithromycin weekly for 3 months reduced recurrent infections caused by susceptible strains of S. aureus by approximately 80%.24

TABLE 88-3 Evidence-Based Recommendations for Treatment of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections5,6,16,30–33

TABLE 88-4 Recommended Oral Drugs or Outpatient Treatment of Mild–Moderate Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Many follicular infections resolve spontaneously without medical or surgical intervention. Lesions should be incised if they do not respond to a few days of moist heat and nonprescription topical agents. Following drainage, most lesions begin to heal within several days without antimicrobial therapy. Any patient who is unresponsive to several days of therapy with a penicillinase-resistant penicillin or first-generation cephalosporin should have a culture and sensitivity performed because of the increasing frequency of CA-MRSA.

ERYSIPELAS

![]() Erysipelas is a distinct form of cellulitis involving the more superficial layers of the skin and cutaneous lymphatics.5,13,24,34 The intense red color and burning pain associated with this skin infection led to the common name of “St. Anthony’s fire.” The infection is almost always caused by β-hemolytic streptococci, with the organisms gaining access via small breaks in the skin. Group A streptococci (S. pyogenes) are responsible for most infections.16,24,31 Infections are more common in infants, young children, the elderly, and patients with nephrotic syndrome.6,31 Erysipelas also commonly occurs in areas of preexisting lymphatic obstruction or edema.13,31 Diagnosis is made on the basis of the characteristic lesion.

Erysipelas is a distinct form of cellulitis involving the more superficial layers of the skin and cutaneous lymphatics.5,13,24,34 The intense red color and burning pain associated with this skin infection led to the common name of “St. Anthony’s fire.” The infection is almost always caused by β-hemolytic streptococci, with the organisms gaining access via small breaks in the skin. Group A streptococci (S. pyogenes) are responsible for most infections.16,24,31 Infections are more common in infants, young children, the elderly, and patients with nephrotic syndrome.6,31 Erysipelas also commonly occurs in areas of preexisting lymphatic obstruction or edema.13,31 Diagnosis is made on the basis of the characteristic lesion.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

TREATMENT

Erysipelas

Desired Outcomes

The goal of treatment of erysipelas is rapid eradication of the infection, thereby providing relief of symptoms (pain, tenderness, fever).34 Preventing recurrent infection is also important, as recurrence is a primary complication, occurring in approximately 20% of patients.24,34 Treatments should be effective and inexpensive and have minimal adverse effects.

Treatment

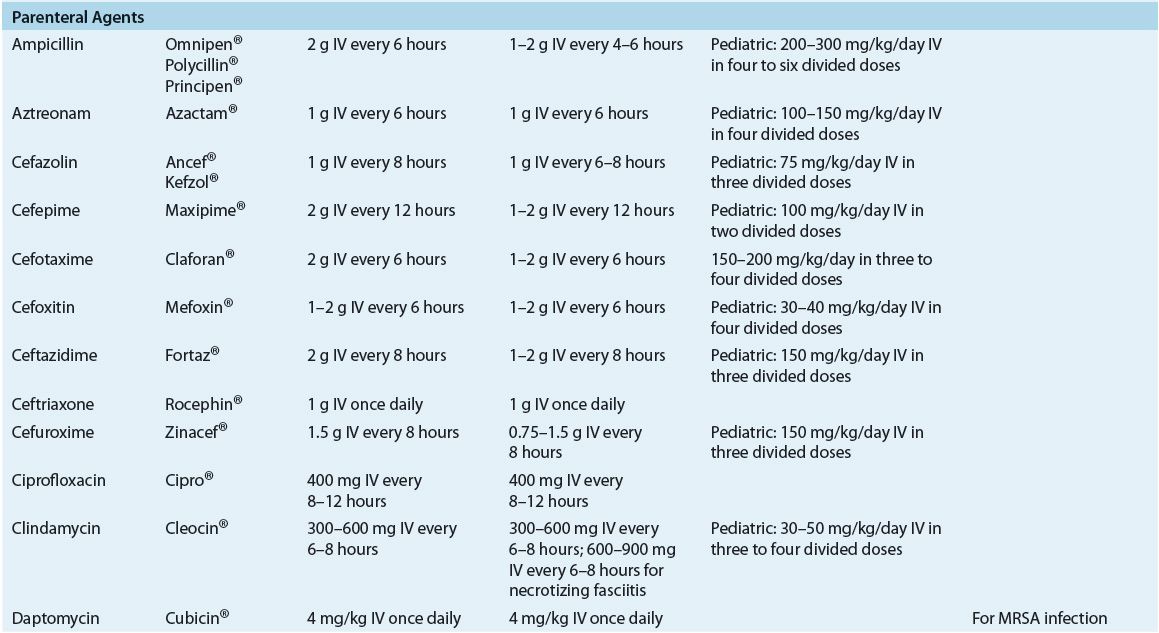

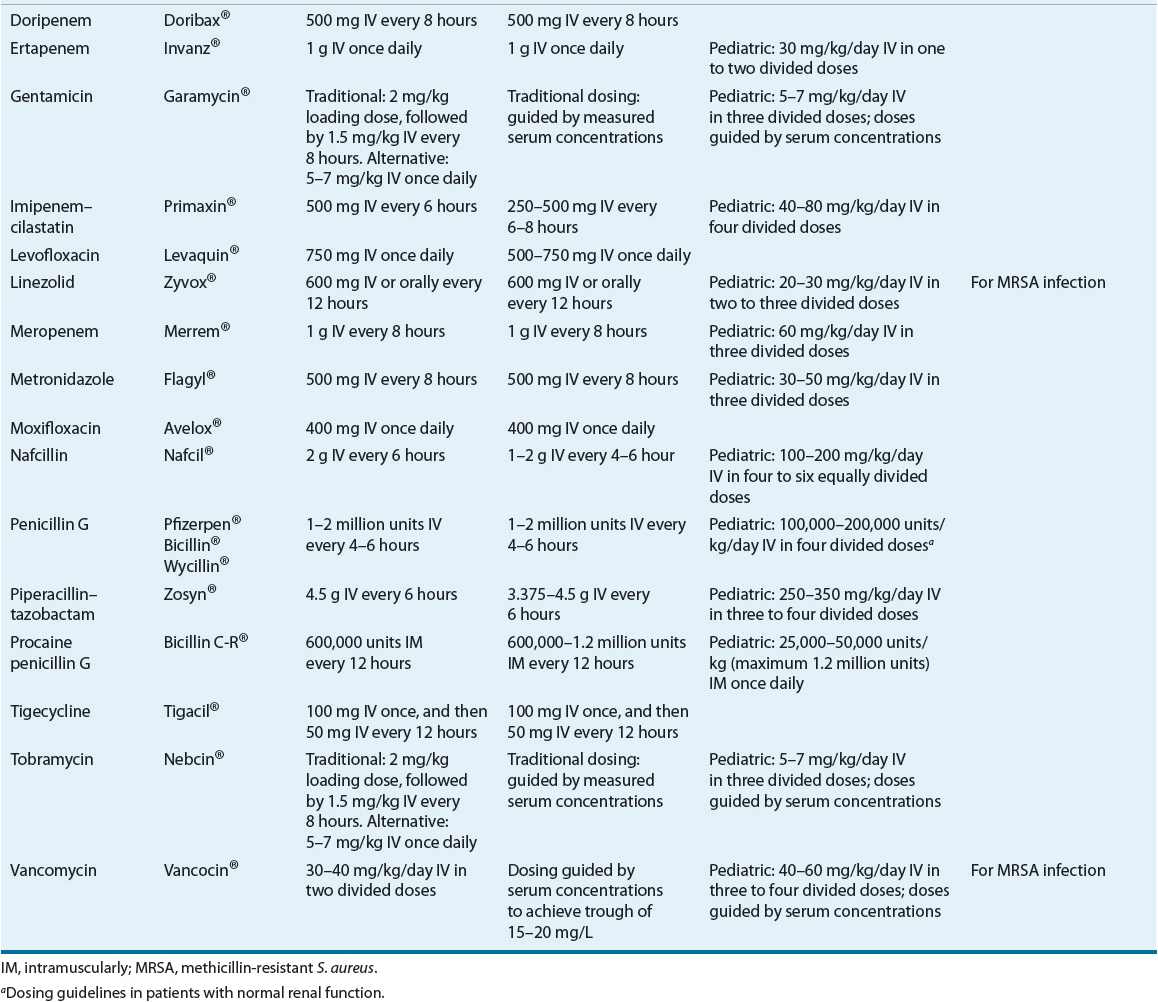

Mild to moderate cases of erysipelas are treated with intramuscular procaine penicillin G or penicillin VK for 7 to 10 days (see Table 88–4).24,31 Recommended doses and monitoring parameters for selected antibiotics are given in Tables 88–5 and 88-6. Penicillin-allergic patients can be treated with clindamycin. For more serious infections, the patient should be hospitalized and aqueous penicillin G administered IV.24,31 Marked improvement usually is seen within 48 hours, and the patient often may be switched to oral penicillin to complete the course of therapy. Although one study has shown that the median time for cure, IV antibiotics, and hospital stay was reduced in patients receiving prednisolone in addition to antibiotics, further studies are needed before corticosteroids can be recommended for routine use.16,31,35

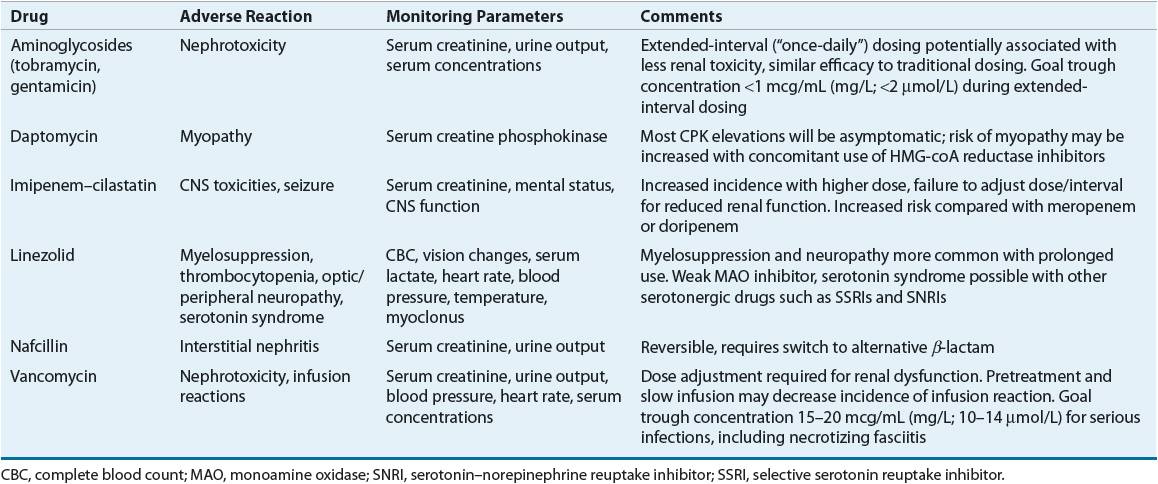

TABLE 88-5 Drug Dosing Tablea

TABLE 88-6 Drug Monitoring

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Erysipelas generally responds quickly to appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Temperature and white blood cell count should return to normal within 48 to 72 hours. Erythema, edema, and pain also should resolve gradually.

IMPETIGO

![]() Impetigo is a superficial skin infection that is seen most commonly in children.6,24,36,37 The infection is generally classified as bullous or nonbullous based on clinical presentation.10,36,37 Impetigo is most common during hot, humid weather, which facilitates microbial colonization of the skin.6,31,36 Minor trauma, such as scratches or insect bites, allows entry of organisms into the superficial layers of skin, and infection ensues.29,31,37 Impetigo is highly communicable and readily spreads through close contact, especially among siblings and children in daycare centers and schools.31,36

Impetigo is a superficial skin infection that is seen most commonly in children.6,24,36,37 The infection is generally classified as bullous or nonbullous based on clinical presentation.10,36,37 Impetigo is most common during hot, humid weather, which facilitates microbial colonization of the skin.6,31,36 Minor trauma, such as scratches or insect bites, allows entry of organisms into the superficial layers of skin, and infection ensues.29,31,37 Impetigo is highly communicable and readily spreads through close contact, especially among siblings and children in daycare centers and schools.31,36

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Although historically caused by S. pyogenes, S. aureus has emerged as a principle cause of impetigo (either alone or in combination with S. pyogenes).24,36,37 The bullous form is caused by strains of S. aureus capable of producing exfoliative toxins.24,36 The bullous form most frequently affects neonates,36 and accounts for approximately 30% of all cases of impetigo.31,36 Similar to other SSTIs, impetigo has been reported to be increasingly due to CA-MRSA.24,37

TREATMENT

Impetigo

Desired Outcomes

The goals of treatment include relieving discomfort, improving the cosmetic appearance of lesions, preventing further spread of the infection, and preventing recurrence. Preventing transmission to others is also important.36,37 Treatments should be effective and inexpensive and have minimal adverse effects.36

Treatment

Although impetigo may resolve spontaneously, antimicrobial treatment is indicated to relieve symptoms, prevent formation of new lesions, and prevent complications such as cellulitis. Penicillinase-resistant penicillins (such as dicloxacillin) are preferred for treatment because of the increased incidence of infections caused by S. aureus.16,24 First-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin) are also commonly used.24 Penicillin, administered as a single intramuscular dose of benzathine penicillin G or as oral penicillin VK, is effective for infections known to be caused by S. pyogenes. Penicillin-allergic patients can be treated with clindamycin. The duration of therapy is 7 to 10 days. A 7-day course of topical therapy with mupirocin ointment or retapamulin ointment is also effective for mild cases.16,24 With proper treatment, healing of skin lesions generally is rapid and occurs without residual scarring. Removal of crusts by soaking in soap and warm water also may be helpful in providing symptomatic relief.24,31

A review of interventions for impetigo by the Cochrane Collaboration found that topical mupirocin and oral antibiotics (except penicillin and erythromycin) were equally effective for the treatment of impetigo.38 Conclusions for extensive impetigo could not be made due to lack of data. Adverse effects were more commonly reported with oral antibiotics (GI) than for topical agents. In addition, disinfectant solutions did not show evidence of benefit.

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Clinical response should be seen within 7 days of initiating antimicrobial therapy for impetigo. Treatment failures could be a result of noncompliance or antimicrobial resistance. A followup culture of exudates should be collected for culture and sensitivity, with treatment modified accordingly.

LYMPHANGITIS

![]() Acute lymphangitis is an inflammation involving the subcutaneous lymphatic channels. Lymphangitis usually occurs secondary to puncture wounds, infected blisters, or other skin lesions. Most infections are caused by S. pyogenes.39

Acute lymphangitis is an inflammation involving the subcutaneous lymphatic channels. Lymphangitis usually occurs secondary to puncture wounds, infected blisters, or other skin lesions. Most infections are caused by S. pyogenes.39

TREATMENT

Lymphangitis

Desired Outcomes

The goal of treatment of lymphangitis is rapid eradication of the infection, thereby providing relief of symptoms (pain, tenderness, fever). Prevention of systemic complications is also an important goal as thrombophlebitis and abscess formation are possible. Treatments should be effective and inexpensive and have minimal adverse effects.

Treatment

Penicillin is the antibiotic of choice. Because these infections are potentially serious and rapidly progressive, initial treatment should be with IV penicillin G 1 to 2 million units every 4 to 6 hours. Parenteral treatment should be continued for 48 to 72 hours, followed by oral penicillin VK for a total of 10 days.39 Nondrug therapy includes immobilization and elevation of the affected extremity and warm-water soaks every 2 to 4 hours.39 For penicillin-allergic patients, clindamycin may be used.

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Lymphangitis usually responds rapidly to appropriate therapy; signs and symptoms often are decreased markedly or absent within 24 hours of starting antibiotics.

CELLULITIS

![]() Cellulitis is an acute infectious process that represents a serious type of SSTI. It initially affects the epidermis and dermis and may spread subsequently within the superficial fascia.10 Cellulitis is considered a serious disease because of the propensity of the infection to spread through lymphatic tissue and to the bloodstream. S. pyogenes and S. aureus are the most frequent bacterial causes.5,7,13,22,29 However, many bacteria have been implicated in various types of cellulitis (Table 88–1). Approximately 4 million patients were hospitalized for cellulitis between 1998 and 2006, representing 10% of all infection-related admissions.12,40 The rising incidence of infections caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a major concern in both the community and hospital settings.14–19,26

Cellulitis is an acute infectious process that represents a serious type of SSTI. It initially affects the epidermis and dermis and may spread subsequently within the superficial fascia.10 Cellulitis is considered a serious disease because of the propensity of the infection to spread through lymphatic tissue and to the bloodstream. S. pyogenes and S. aureus are the most frequent bacterial causes.5,7,13,22,29 However, many bacteria have been implicated in various types of cellulitis (Table 88–1). Approximately 4 million patients were hospitalized for cellulitis between 1998 and 2006, representing 10% of all infection-related admissions.12,40 The rising incidence of infections caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a major concern in both the community and hospital settings.14–19,26

Injection drug users are predisposed to several infectious complications, including abscess formation and cellulitis at the site of injection.16 These SSTIs are often polymicrobic in nature and are believed to originate from the skin and/or oropharynx, as well as from contaminated needles, syringes, and diluents.16 S. aureus is the most common pathogen isolated from injection drug users; the incidence of MRSA is also rising.14,16,41 Anaerobic bacteria, especially oropharyngeal anaerobes, are also found commonly, particularly in polymicrobic infections.16 Outbreaks caused by Clostridium species have also been reported in injection drug users, particularly in association with contaminated black tar heroin.16

Acute cellulitis with mixed aerobic and anaerobic pathogens may occur in diabetics, following traumatic injuries, at sites of surgical incisions to the abdomen or perineum, or where host defenses have been otherwise compromised (vascular insufficiency).6,10,29 In older patients, cellulitis of the lower extremities also may be complicated by thrombophlebitis. Other complications of cellulitis include local abscess, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.16,42

TREATMENT

Cellulitis

Desired Outcomes

The goals of therapy of acute bacterial cellulitis are rapid eradication of the infection and prevention of further complications. Effective treatment of cellulitis includes avoidance of unnecessary antimicrobials that contribute to increased resistance, and minimizing toxicities and cost of therapy.

Drug and Nondrug Management of Cellulitis

Local care of cellulitis includes elevation and immobilization of the involved area to decrease swelling.5,43 Cool sterile saline dressings may decrease pain and can be followed later with moist heat to aid in localization of the cellulitis. Surgical intervention (incision and drainage) as a mode of therapy is rarely indicated in the treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis, but may play an important role in management of more severe or complicated cases. Antimicrobial therapy is directed against the type of bacteria either documented or suspected to be present based on the clinical presentation. Particular attention must be paid to patients with risk factors for more atypical or resistant bacterial pathogens when selecting antibiotics for treatment of cellulitis. Such organisms include particularly CA-MRSA, but also aerobic gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Because staphylococcal and streptococcal cellulitis are indistinguishable clinically,22,42 and because of concern regarding appropriate recognition and treatment of MRSA infections, guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America provide detailed recommendations for empiric antibiotic therapy of cellulitis.32 Infection with CA-MRSA should be considered in patients with skin abscesses, subjective history of insect bites, or more severe infections.32,42 Appropriate clinical specimens for culture and susceptibility testing should be collected whenever possible in such patients.5,32,42 Incision and drainage is the primary therapy for infections such as small abscesses and furuncles, and in otherwise uncomplicated patients with mild infections. Systemic antibiotic therapy is often unnecessary in such cases.32 Antibiotic therapy is recommended along with incision and drainage in patients with more complicated abscesses associated with the following: severe or extensive disease involving multiple sites of infection; rapidly progressive infection in the presence of associated cellulitis; signs and symptoms of systemic illness; complicating factors such as extremes of age, comorbidities, or immunosuppression; abscesses in areas that are difficult to drain, such as hands, face, and genitalia; or lack of response to previous drainage alone.32,42,44–47

Antibiotic selection for outpatient treatment of cellulitis is chiefly determined by clinical findings such as appearance of the infected lesion and presence of more severe systemic illness. Purulent cellulitis is defined as infection associated with purulent drainage or exudate in the absence of a drainable abscess.32 Empiric antibiotics for purulent cellulitis in outpatients should include an orally administered agent with activity against CA-MRSA such as trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, a tetracycline, or clindamycin (Table 88–7); infection due to streptococci is less likely in this situation and specific coverage is not required.32,48–50 Oral linezolid is also recommended in such cases but is significantly more expensive and no more efficacious than other treatment options.32

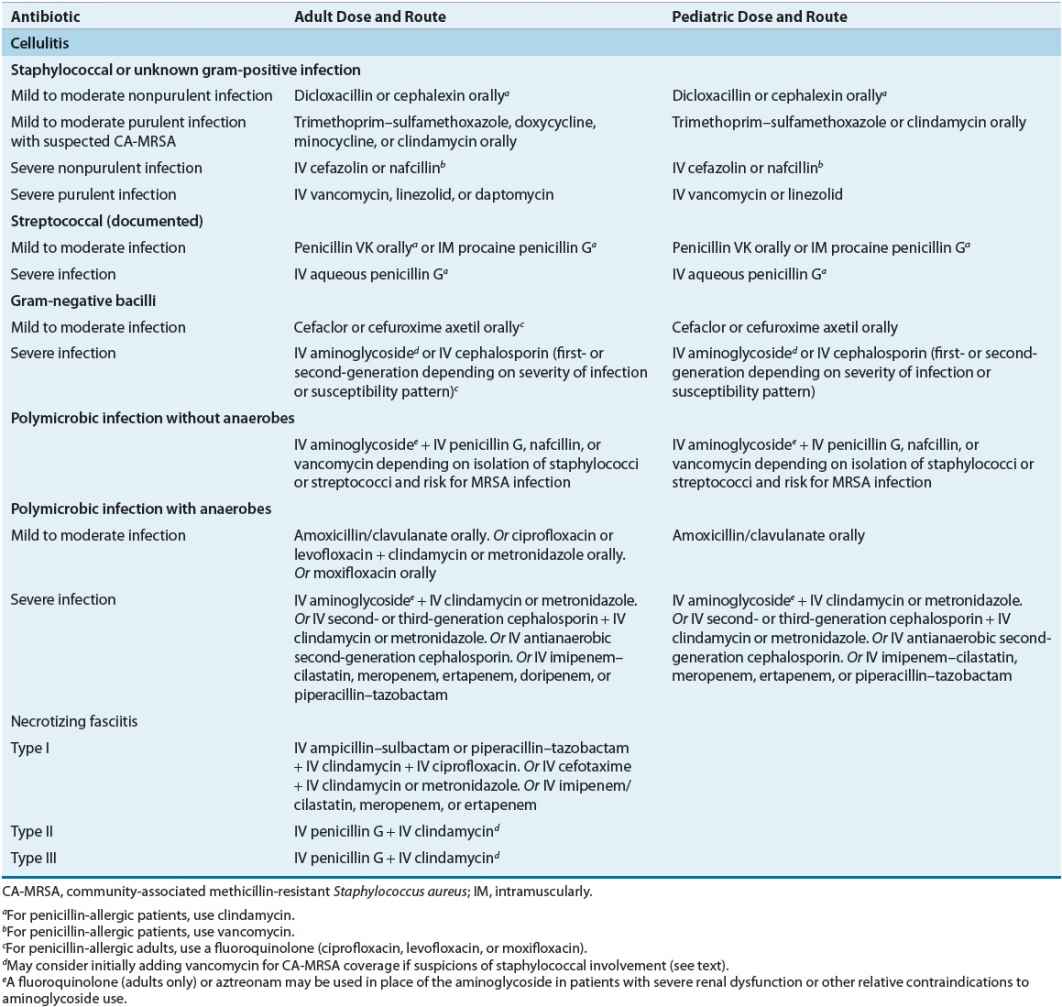

TABLE 88-7 Initial Treatment Regimens for Cellulitis and Necrotizing Fasciitis

Clinical Controversy…

< div class='tao-gold-member'>