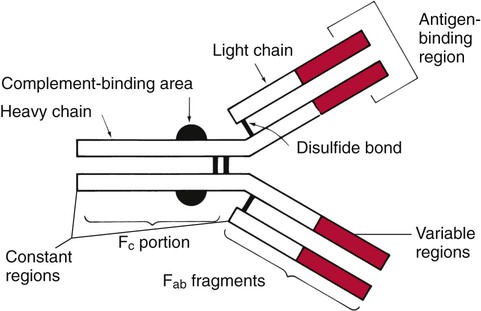

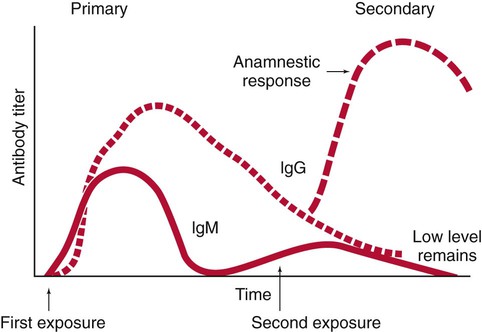

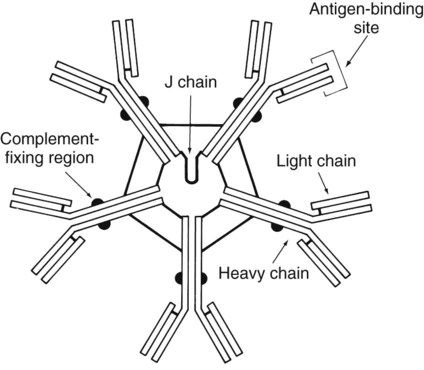

1. Define the two categories of human specific immune response, cell mediated and antibody mediated, including the definition of T cells and B cells and their role in the responses. 2. List the five classes of antibodies, define their roles in infectious disease, and explain the three antibody functions. 3. Explain the following serologic tests, giving consideration to their clinical applications: bacterial agglutination, particle agglutination, and flocculation tests. 4. Describe a cross reaction and explain why it occurs and how it may affect antibody testing. 5. In defining hemagglutination and neutralization assays, explain their similarity in testing, along with their disparities. 6. Explain how the difference in the size and structure of the IgM antibody is important to its activity and function. 7. Explain what the complement fixation test is and describe the two-step reaction. 8. Explain the principle of the Western blot assay and why it is used as a confirmatory test for many assays. Immunochemical methods are used as diagnostic tools for serodiagnosis of infectious disease. An understanding of how these methods have been adapted for this purpose requires a basic working knowledge of the components and functions of the immune system. Immunology is the study of the components and functions of the immune system. The immune system is the body’s defense mechanism against invading “foreign” antigens. One of the functions of the immune system is distinguishing “self” from “nonself” (i.e., the proteins or antigens from foreign substances). (Chapter 3 presents a more in-depth discussion of the host’s response to foreign substances.) This chapter is intended to provide a brief overview and review of immunology. The complexity and detail required to fully understand immunology and serology are beyond the scope of this text. The basic structure of an antibody molecule comprises two mirror images, each composed of two identical protein chains (Figure 10-1). At the terminal ends are the antigen binding sites, or variable regions, which specifically attach to the antigen against which the antibody was produced. Depending on the specificity of the antibody, antigens of some similarity, but not total identity, to the inducing antigen may also be bound; this is called a cross reaction. The complement binding site is found in the center of the molecule in a structure similar for all antibodies of the same class and is referred to as the constant region. IgM is produced as a first response to many antigens, although the levels remain high transiently. Thus, the presence of IgM usually indicates recent or active exposure to an antigen or infection. IgG, on the other hand, may persist long after an infection has run its course. The IgM antibody type (Figure 10-2) consists of five identical proteins (pentamer), with the basic antibody structures linked at the bases with 10 antigen binding sites on the molecule. IgG consists of one basic antibody molecule (monomer) that has two binding sites (see Figure 10-1). The differences in the size and conformation between these two classes of immunoglobulins result in differences in activities and functions. IgG is often more specific for the antigen (i.e., it has higher avidity). IgG has two antigen binding sites, but it can also bind complement. Complement is a complex series of serum proteins that is involved in modulating several functions of the immune system, including cytotoxic cell death, chemotaxis, and opsonization. When IgG is bound to an antigen, the base of the molecule (Fc portion) is exposed in the environment. Structures on this Fc portion attract and bind the cell membranes of phagocytes, increasing the chances of engulfment and destruction of the pathogen by the host cells. A second exposure to the same pathogen induces a faster and greater IgG response and a much lesser IgM response. Several B lymphocytes retain memory of the pathogen, allowing a more rapid response and a higher level of antibody production than the primary exposure or response. This enhanced response is called the anamnestic response. B-cell memory is not perfect. Occasional clones of memory cells can be stimulated through interaction with an antigen that is similar but not identical to the original antigen. Therefore, the anamnestic response may be polyclonal and nonspecific. For example, reinfection with cytomegalovirus may stimulate memory B cells to produce antibody against Epstein-Barr virus (another herpes family virus), which the host encountered previously, in addition to antibody against cytomegalovirus. The relative humoral responses are diagrammatically represented in Figure 10-3. Table 10-1 provides a brief list of representative serologic tests available for immunodiagnosis of infectious diseases, the specimen required, interpretation of positive and negative test results, and examples of applications of each technique. Because serologic assays are rapidly evolving, this table is not intended to be all-inclusive. TABLE 10-1 Noninclusive Overview of Tests Available for Serodiagnosis of Infectious Diseases

Serologic Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

Features of the Immune Response

Characteristics of Antibodies

Features of the Humoral Immune Response Useful in Diagnostic Testing

Serodiagnosis of Infectious Diseases

Test

Sera Needed

Interpretation

Application

IgM

Single, acute (collected at onset of illness)

Newborn, positive: in utero (congenital) infection

Adult, positive: primary or current infection

Adult, negative: no infection or past infection

Newborn: STORCH* agents; other organisms

Adults: any infectious agent

IgG

Acute and convalescent (collected 2-6 weeks after onset)

Positive: fourfold rise or fall in titer between acute and convalescent sera tested at the same time in the same test system

Negative: no current infection or past infection, or patient is immunocompromised and cannot mount a humoral antibody response, or convalescent specimen collected before increase in IgG (Lyme disease, Legionella sp.)

Any infectious agent

IgG

Single specimen collected between onset and convalescence

Adult, positive: adult evidence of infection at some unknown time except in certain cases in which a single high titer is diagnostic (rabies, Legionella, Ehrlichia spp).

Newborn, positive: maternal antibodies that crossed the placenta

Newborn, negative: patient has not been exposed to microorganism or patient has a congenital or acquired immune deficiency or specimen collected before increase in IgG (Lyme disease or Legionella sp.)

Any infectious agent

Immune status evaluation

Single specimen collected at any time

Positive: previous exposure

Negative: no exposure

Rubella testing for women of childbearing age, syphilis testing may be required in some states to obtain a marriage license, cytomegalovirus testing for transplant donor and recipient ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Serologic Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases