Selective Vagotomy, Antrectomy, and Gastroduodenostomy for the Treatment of Duodenal Ulcer

Lloyd M. Nyhus

The surgical treatment of complicated duodenal ulcer has undergone marked change since vagotomy was reintroduced by Dragstedt and Owens in 1943. Subtotal gastrectomy alone had been the mainstay operation for the prior 50 years, followed by various surgical procedures, including truncal vagotomy, gastroenterostomy, pyloroplasty, 70% subtotal gastrectomy, and antrectomy. My experience with the combined operation of truncal vagotomy, antrectomy, and gastroduodenostomy began in the early 1950s. It became apparent that the method of vagotomy could be improved. Therefore, my associates and I modified our technique of vagotomy to the selective method and changed the name of the procedure to the “revised combined operation.” Thus, the specific procedure included selective vagotomy, antrectomy (35% distal gastrectomy), and gastroduodenostomy (Billroth I anastomosis). This operation has a good record in terms of ulcer recurrence. The recurrent ulcer rate after this procedure should be no greater than 0.5%.

Because of the interest in proximal gastric vagotomy, we have departed from gastrectomy as a routine operative procedure in our clinic. Yet, because of the occasional need to perform a partial gastrectomy or antrectomy, the technical lessons we learned must not be forgotten. For this reason, I highlight the classic “revised combined operation of Harkins” in this chapter.

Failure to appreciate technical details is reflected not only in resultant anatomic disturbances such as postoperative suture line leakage, but also in physiologic effects (e.g., recurrent ulcer from incomplete vagotomy). My experience in performing the revised combined operation (i.e., selective vagotomy plus antrectomy plus gastroduodenostomy) has led to the modification of certain steps in the technique.

Surgery is an art, and, like all art, it must be developed, not discovered. The technique described is the one that seems to give the best results at the present time. Much of the following surgical technique is applicable to the Billroth II procedure as well as to the Billroth I operation.

General Principles

Sutures

A variety of sutures are used throughout the operation. Whereas fine silk was used predominantly in the past, new absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures may be used now. Most vessels are simply ligated, but transfixion sutures are occasionally used. An absorbable suture is used essentially as a mucosal stitch with inversion for the inner layer of the anastomosis. Seromuscular sutures continue to be of 4-0 or 3-0 black silk. The abdominal wall closure has changed from silk to stainless-steel wire sutures to the current use of several monofilament synthetic sutures.

Open Anastomosis

I prefer the open to the closed type of anastomosis for several reasons. First, because the open technique provides direct visualization at all times, bleeding from the anastomosis can be entirely prevented. Second, the size of the anastomotic stoma can be ensured, and the surgeon can be certain that the anterior and posterior walls are not included in one or more sutures. Third, through the open duodenal stump, the ampulla of Vater can be palpated and biliary flow can be noted; also, the area can be inspected for postbulbar duodenal ulcer and other duodenal abnormalities. I have seen no difficulty arise from soiling of the surgical field with the use of the open technique. The bacterial flora of the stomach and duodenum are few if there is no distal obstruction, and adequate protection can be achieved by careful placement of laparotomy pads to protect the remainder of the operative field. An inner mucosal or full-thickness layer of continuous absorbable sutures and an outer seromuscular layer of interrupted silk sutures are routine to complete the anastomosis.

Drainage

If it is suspected that the pancreas has been subjected to undue surgical trauma, a Penrose drain or a double-lumen sump-suction catheter can be placed down to the site of suspected injury and brought out laterally through the abdominal wall via a stab wound; it is never brought through the main incision. Rarely, I place a Penrose drain near, but not on, the anastomosis if some aspect of the coaptation causes concern.

Adequacy of Resection

I adhere inviolably to the dictum that an adequate resection must be performed on the basis of the presenting disease before any decision is made to use or not to use any particular type of anastomosis. In fact, this decision is not made until the anastomosis is to be done. If there is any tension whatsoever in attempting to perform a gastroduodenal anastomosis, this method is abandoned and a modification of the Billroth II procedure is used. The anastomosis should not be forced. In general, the resection may be only 35% when protected by selective vagotomy.

Protection of Vital Structures

The only way to avoid injury to important structures is to visualize the part of the structure that lies in the field of dissection. The inflammatory reaction and scarring characteristic of many gastroduodenal lesions can cause distortion of the normal anatomy. This distortion, coupled with the extreme variability in “normal” anatomy, makes dissection in this region extremely hazardous unless good visualization or identification of the vital structures to be preserved is constantly sought.

The simple maneuver of opening the common bile duct in certain instances is useful when the porta hepatis is involved in ulcer scar or inflammatory reaction. It is important to recognize the possible distortion of normal anatomic configurations of the common bile duct and the pancreatic ducts. A catheter or Bakes bile duct dilator introduced via choledochotomy is reassuring when dissecting a duodenum that is thickened, distorted, or inflamed. Special care should be taken to avoid injury to the common hepatic artery, which sometimes can be retracted near a posterior penetrating duodenal ulcer crater. On the greater curvature

side of the pyloric region, the middle colic artery can be so densely adherent to the ulcer scar that it easily may be mistaken for the right gastroepiploic artery.

side of the pyloric region, the middle colic artery can be so densely adherent to the ulcer scar that it easily may be mistaken for the right gastroepiploic artery.

Caution should be used to avoid vigorous palpation or traction in the region of the spleen. The splenic vessels, particularly in older persons, are friable and easily torn. Moderate traction on the greater curvature of the stomach is sufficient to cause tearing of the splenic vessels or of the splenic substance. When such an accident occurs, appropriate splenic repair should be carried out; splenectomy may be necessary if the bleeding cannot be controlled with argon beam coagulation. Splenectomy is not a catastrophe; it can appreciably increase morbidity and even mortality.

The tenets of good modern surgery—the gentle handling of tissues, the avoidance of undue traction, and meticulous identification of adjacent structures to be preserved—are essential to a technically satisfactory operation.

Avoidance of Mass Ligatures

In dividing the blood supply to the portion of the stomach and duodenum to be resected, it is important that small bites of tissue be ligated. Especially in patients with a large quantity of omental fat, there is a tendency, if the vessel ligatures are placed around large quantities of this fat, for the vessels to retract proximal to the ligature and cause troublesome hematomas or a dangerous hemorrhage. Particularly in older people, I have been impressed with the increased quantity of fat that surrounds the left gastric vessels high on the lesser curvature. This situation is observed even in thin elderly patients.

Removal of Ulcer

In association with gastric resection, I regularly remove the duodenal ulcer for mechanical rather than physiologic reasons. Only rarely do I leave a duodenal ulcer in situ. However, I do not hesitate to leave the depths of an ulcer crater in the tissue into which it may have penetrated.

Technical Procedure

Only the combined operation of selective vagotomy plus hemigastrectomy (antrectomy) plus gastroduodenal anastomosis is described in this section. The sequence of performance of the various steps applies to most operations. However, certain conditions germane to each situation can make a somewhat altered sequence more desirable. A step-by-step description of the technique is undertaken merely because it is easier to describe it in this manner. It is the integration of all these steps into a smoothly performed surgical procedure that is productive of technical satisfaction.

The surgical technique I prefer (Table 1) is described in the following 11 steps.

Incision

An upper midline abdominal incision is used almost exclusively. This incision is begun in the left xiphocostal angle and is extended down the linea alba to the level of the umbilicus or below, if necessary. The incision is usually approximately 15 cm long. In patients for whom the distance between the costal arch and the umbilicus is short, I extend the incision inferiorly to one side of the umbilicus. If more room is needed proximally, I excise the xiphoid process. The peritoneum is cut approximately 2 cm to the left and lateral to the skin and fascial incision, which gives a “staggered” effect so that the underpart of the fascial closure is more or less protected by the intact peritoneum.

Abdominal Exploration

The surgeon must curtail his or her enthusiasm to attack the gastroduodenal disease for which the operation was performed until there is ample opportunity to explore the entire peritoneal cavity. Unless a general exploration is performed as soon as the peritoneal cavity is entered, this important step is apt to be forgotten. In addition, it is probably a better technique to explore the general peritoneal cavity before the gastrointestinal tract has been entered to avoid the small but ever-present chance of disseminating contaminated debris. Two exceptions to the rule of exploring the general abdominal cavity before beginning the gastric procedure are emergency operations for a bleeding gastroduodenal lesion, when control of the hemorrhage should take priority, and operations for obvious acute perforation of a peptic ulcer.

It is only after adequate inspection of the gastroduodenal disease that the final decision to perform a gastric procedure should be made. This decision should, however, depend on the sum total of information available about the patient and not solely on the findings at the operation. Most often, the presence of an active ulcer, ulcer scar, or carcinoma of the stomach can be detected by external inspection and palpation. Occasionally, a posterior duodenal or a lesser curvature gastric ulcer can be identified by palpating the crater through the anterior wall of the duodenum or stomach. Often, after rapid withdrawal of the palpating finger, the anterior wall of the duodenum or stomach can be observed to remain depressed into the crater by a suction effect.

Selective Vagotomy

Henry Harkins and Charles Griffith of Seattle (1957) are credited with modification of the truncal (total) vagotomy method to the selective technique, which preserves all extragastric vagal fibers. The late Professor Griffith fine-tuned these important advances in technique. To commemorate his contribution, I have paraphrased his 1977 and 1986 presentations.

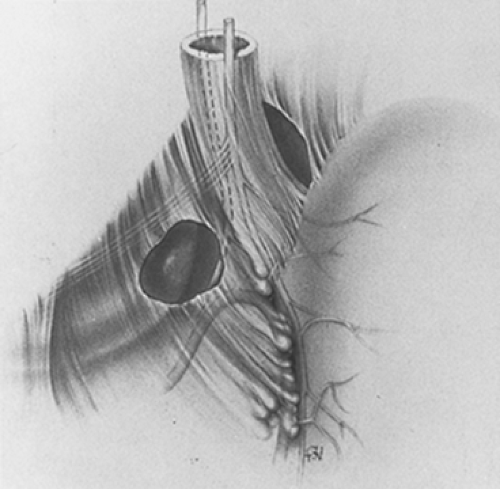

An essential difference between truncal and selective vagotomy concerns the different anatomic levels at which vagotomy is performed. Truncal vagotomy is conventionally performed at or just above or below the diaphragmatic esophageal hiatus. In contrast, selective vagotomy is performed at the lower level of the most distal esophagus and gastric cardia (Fig. 1). The lower level is selected because it is the only place where all gastric vagi always gather to innervate the stomach. In taking advantage of this fundamental anatomic fact, all gastric vagi can be encircled and brought into the surgical field with anatomic certainty. This is the first and basic requirement for accomplishing complete gastric vagotomy, and it is in definite contrast with the uncertain encirclement at the hiatus, where incomplete vagotomy can and does occur because the encircling finger may exclude one or more vagal fibers.

Selective Technique

Selective gastric vagotomy entails ligation and transection of all the previously described encircled tissues, except for the esophagus and the hepatic and celiac vagal branches. In addition, the descending branch of the left gastric artery must also be ligated and transected to interrupt posterior gastric vagi that may arise distally from the celiac division of the posterior trunk and may go to the stomach and the left gastric artery. Neither the hiatus nor the vagal trunks are dissected or exposed. Furthermore, the gastric vagi are not purposely exposed or identified. Instead, all tissues known to contain the gastric vagi are clamped, ligated, and transected.

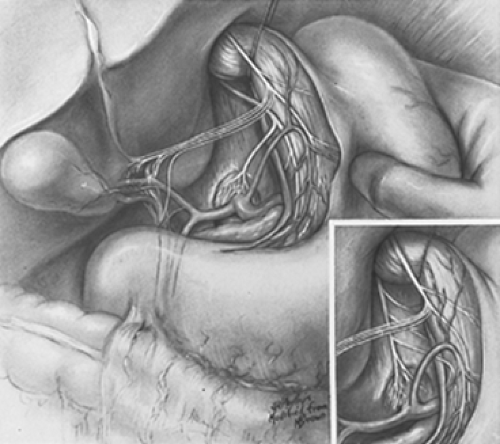

For initial definition of the surgical field, the esophageal hiatus and vagal trunks are not exposed purposely. Instead, the hepatic vagi are identified. These vagi can always be seen in the avascular lesser

omentum contrasted against the dark background of the caudate lobe of the liver (Fig. 2). The lesser omentum is incised below the hepatic vagi, well to the right of the patient’s gastric cardia. No gastric vagi lie to the right of this incision in the lesser omentum. Next, the peritoneum that overlies the cardioesophageal angle of His is incised, and this opening is enlarged with the finger. No gastric vagi lie to the patient’s left of this opening at the angle of His. Thus, all anterior gastric vagi are included between these two incisions in the lesser omentum and angle of His. None has been excluded.

omentum contrasted against the dark background of the caudate lobe of the liver (Fig. 2). The lesser omentum is incised below the hepatic vagi, well to the right of the patient’s gastric cardia. No gastric vagi lie to the right of this incision in the lesser omentum. Next, the peritoneum that overlies the cardioesophageal angle of His is incised, and this opening is enlarged with the finger. No gastric vagi lie to the patient’s left of this opening at the angle of His. Thus, all anterior gastric vagi are included between these two incisions in the lesser omentum and angle of His. None has been excluded.

The method of encircling all posterior gastric vagi cannot be illustrated. It is done by finger dissection. The finger is worked into the angle of His, not with the aim of encircling the esophagus, but with the aim of palpating the posterior trunk–celiac division posterior to the esophagus. Once the posterior trunk–celiac division has been positively identified by palpating its course to the celiac plexus, the finger is dissected through the areolar tissue behind (i.e., dorsal to) the posterior trunk–celiac division. This technique isolates all posterior gastric vagi because none lies behind the division. At this point, the fingertip may be seen through the incision in the lesser omentum initially made below the hepatic vagal branches (Fig. 3). The encirclement of all gastric vagi with the most distal part of the esophagus is thereby accomplished with anatomic certainty. The encircling finger is replaced by a soft rubber urethral catheter to maintain encirclement and exposure.

By finger dissection, the posterior trunk–celiac division is mobilized from its bed and is encircled with another rubber urethral catheter so that it may be gently retracted to the patient’s right (Fig. 4). The original catheter is then repositioned to encircle all anterior gastric vagi with the most distal part of the abdominal esophagus, which then may be retracted to the patient’s left.

Attention is now directed to the loop of the left gastric artery, where it approaches the lesser curvature of the stomach and bifurcates into the descending gastric and ascending esophageal branches. I prefer finger dissection to isolate the descending left gastric artery to facilitate the transection of any posterior gastric vagi that may accompany that vessel to the stomach. Then, as indicated by the dashed line in Figure 5, the lesser curvature is freed entirely from the gastric cardia by successive transactions between clamps and ligation up to the encircling catheters to facilitate the transection of any other posterior gastric vagi. Clearly, this dissection is the step that makes selective vagotomy more difficult than total vagotomy. It may be more complicated if an aberrant left hepatic artery from the left gastric artery is encountered (not illustrated, but present in approximately 10% of patients). By transecting all lesser omental attachments to the gastric cardia, thereby totally separating the posterior trunk–celiac division from the distal esophagus and gastric cardia, all posterior gastric vagi are severed (Fig. 6).

All remaining tissue anterior to the esophagus (i.e., all tissue between the original incisions in the lesser omentum and angle of His) is dissected from the esophagus with the finger before division between right-angle clamps and ligation. This tissue contains all anterior gastric vagi and some esophageal vessels (Fig. 7).

The distal esophagus and gastric cardia are now completely separated from their attachments to all other tissue, including the vagal trunks (Fig. 8). The only gastric vagi that can remain are small twigs that may have arisen from the main vagal trunks or esophageal plexus above the surgical field. The usual careful search for the small twigs is, therefore, carefully conducted in and beneath the esophageal fascia propria. The esophageal muscle is thereby bared in its entire circumference. The esophageal muscle is not violated because any nerves found within the muscle innervate the esophagus, not the stomach. Two encircling fingers are used to feel for any intact fibers around the distal esophagus.

Freeing of the Greater Curvature

The gastrocolic omentum is perforated in an avascular portion by a curved hemostat, thus permitting the lesser peritoneal sac to be entered. Unless care is taken in the execution of this maneuver, the middle colic vessels can be damaged. To minimize the possibility of such an error, it is recommended that the anterior wall of the stomach and the transverse colon be elevated and gently pulled apart to tense the gastrocolic omentum. It is easier to find a good cleavage plane by entering the gastrocolic omentum at the level of the junction of the lower and middle third of the greater curvature of the stomach, or even farther to the left; usually, most of the adhesions that tend to obliterate the lesser peritoneal sac are found in the region of the pylorus and lower third of the stomach. At the higher level, it is easy to identify an avascular area between the main trunk of the gastroepiploic vessels and the colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree