18

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: CLINICAL GUIDELINES

■ CURRENT EVIDENCE ON SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: A BRIEF SUMMARY

■ SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSES OF SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTIONS FOR UNHEALTHY ALCOHOL USE

■ INDIVIDUAL STUDIES OF SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION FOR UNHEALTHY ALCOHOL USE

■ INDIVIDUAL STUDIES OF SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION FOR UNHEALTHY DRUG USE

■ SUMMARY

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) occur in 10% to 20% of patients presenting to the offices of primary care physicians and admitted to a hospital. The AUD frequency varies by age, culture, and comorbid medical and mental health problems; these rates are higher in trauma patients and those presenting to emergency departments (EDs) and approach 50% in some high-risk settings. Rates of illicit and prescription drug use disorders in primary care and hospital settings vary from 5% to 10% with considerable overlap with AUDs. Prescription opioid abuse is becoming an increasing problem and has been called a “national epidemic” (1). In general, unhealthy substance use is an enormous burden to the health care system with no easy solution.

What is a doctor supposed to do when such a large proportion of patients coming into the office has an unhealthy alcohol and/or drug use? Every day, a primary care physician will provide medical care to three to five patients with unhealthy alcohol or drug use. How should hospital-based physicians care for the one in five admissions directly related to substance use? What is the appropriate response for health care systems, payors, and hospitals? How do physicians manage the complex comorbidities that are closely associated with alcohol and drug use? A number of serious medical problems, including death, liver failure, hypertension, obesity, glucose intolerance, and memory loss, and a variety of other medical and mental health conditions are directly related to unhealthy alcohol use. One promising and now well-established approach to alleviate these problems is screening and brief intervention (SBI) and—when appropriate—a referral to a specialty, addiction treatment program (SBIRT). With positive research findings growing stronger every year on its efficacy and effectiveness, SBI is becoming a part of the recommended “usual” care in certain clinical settings.

Brief intervention (BI) is one of the many treatment methods available to help patients with unhealthy alcohol and drug use. BI is a time-limited, client-centered counseling session designed to reduce substance use. Although it is generally delivered by a health care professional in the context of routine clinical care, more recent research has also lent support for effectiveness of nondirect SBI delivery, by phone or via Web. The average duration of a BI ranges from 5 to 20 minutes. Studies suggest that multiple BI sessions are more effective than a single contact. Having an established relationship with a patient can increase the likelihood of success. What is important for clinical practice is that BI does not seem to be linked to a patient’s stated “readiness to change” and can work in pre-contemplators as well as persons who are ready to change.

One of the primary differences between BI and other therapies ranging from behavioral and pharmacologic professional treatments to self-help meetings such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is the treatment goal. BI is based on a harm reduction paradigm that emphasizes reduction in use rather than abstinence-only in order to reduce the risk of negative, drinking-related consequences (e.g., trauma, depression, hypertension, or violence). There is a clear dose–response relationship between the level of alcohol consumption and the risk for alcohol-related harms. For example, patients who drink four or more drinks per day have a two- to threefold increase in the risk of a fatal accident and the development of liver failure, cancer, or ischemic heart disease; if the patient can reduce alcohol use to one to two drinks per day and does not drink more than three to four drinks on an occasion, the risk of harm will be substantially reduced.

SBI has been studied and used in clinical practice for a long time. Although most physicians have received limited formal training in brief “talk therapy” or brief counseling, it is one of the essential elements of being a physician. SBI technique is one of the most popular clinical “tools” utilized by primary care providers who employ the SBI basics with nearly every patient to facilitate a trusting healing relationship and change a variety of harmful behaviors including smoking, overeating, poor medication compliance, or sedentary lifestyle. SBI can be viewed as a part of the clinician’s responsibilities, in addition to ordering tests, performing surgical procedures, prescribing medications, and filling out medical records.

NATIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF UNHEALTHY SUBSTANCE USE SCREENING AND TREATMENT IN MEDICAL CARE SETTINGS

Over the past almost five decades, research has demonstrated the potential benefits of SBI as a brief behavioral therapy for tobacco and unhealthy alcohol use in a variety of public health and clinical settings. Based on this evidence, recent years have witnessed structured efforts to disseminate SBI into clinical practice.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine SBI to reduce alcohol “misuse” by adults, including pregnant women in primary care settings (Grade B) (2), and strongly recommends that clinicians screen all adults, including pregnant women, for tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for tobacco users (Grade A) (3). The USPSTF concludes though the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine SBI to prevent or reduce alcohol misuse or tobacco use among children and adolescents. The USPSTF has found insufficient evidence to recommend universal SBI for illicit drug use (4).

Most professional medical organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the American College of Surgeons (ACS), have adopted policies calling on their members to be knowledgeable, trained, and involved in all phases of prevention and SBI for alcohol, tobacco, and other drug problems. The ACS Committee on Trauma requires screening of all level I and level II trauma patients for unhealthy alcohol use as well as providing BI for those patients who screen positive in level I trauma centers (5). Recommendations to implement SBI in general and mental health care settings have been endorsed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the National Quality Forum (NQF), a voluntary consensus evidence-based standard-setting organization. In general, the professional organizations recommend alcohol, tobacco, and drug SBI for adults and adolescents. The specific age of onset of such services is less well defined, though. The NQF recommends alcohol and tobacco SBI services for patients 10 years of age or older during new patient encounters and at least annually (6). The NIAAA recommends alcohol screening starting even earlier, at age 9, and provides a clear algorithm for youth SBI in its new Guide for Youth (7). The NIDA tools have been developed for drug misuse SBI in adults (8). The AAFP endorses SBI for unhealthy substance use for both adults and adolescents (9).

Recent changes in the “medical marijuana” regulations, combined with the fact that marijuana is the most widely used illegal drug in the United States (10), often bring questions about this substance, especially when it is used by patients who are prescribed controlled substances with addictive potential, for example, opioids. Although the AAFP opposes the recreational use of marijuana, in regard to the medical use of marijuana, the AAFP defers to federal and state laws (9). The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) “opposes proposals to legalize marijuana anywhere in the United States …. The analyses on the possible outcomes—both intended and unintended—of the state-based marijuana legalization proposals … suggest that risks are unacceptable” (11).

Adoption of billing codes by the AMA and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for tobacco as well as alcohol/substance abuse–structured SBI services represents a major step toward dissemination of SBI in clinical settings. Details on coding and reimbursement are available online (12–15). In addition, Medicare waives coinsurance, copayment, or deductible for the preventive services graded as A or B by the USPSTF that include alcohol and tobacco SBI for adults and pregnant women in primary care. Medicare has specific regulations about the settings of SBI delivery. It covers tobacco cessation SBI for both outpatient and inpatient beneficiaries. It also covers annual screening for unhealthy alcohol use and—for those who screen positive and are diagnosed with at-risk use or abuse (but not dependence)—up to four brief face-to-face counseling interventions in a 12-month period. Each intervention should be consistent with the Five A’s approach (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) and provided by a qualified physician (general practice, family medicine, geriatrics, pediatrics, internal medicine, or OB/GYN) or other recognized clinician in primary care settings that, of note, exclude EDs or skilled nursing facilities. Medicare does not identify specific tools to screen for or diagnose unhealthy alcohol use; they can be chosen, as appropriate, by the clinician.

SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: CLINICAL GUIDELINES

If you aren’t already doing so, we encourage you to incorporate alcohol screening and intervention into your practice. You’re in a prime position to make a difference.

These first lines of the booklet “Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide” summarize the current NIAAA guidelines on alcohol SBI in primary care and mental health settings (16). While this guide provides an algorithm for a step-by-step approach to alcohol SBI for adults, another guide recently released by the NIAAA addresses nuances of alcohol SBI delivery in youth (7). Both guides are available in both extended (yet concise) and pocket (one small booklet) sizes (7,16–18). While focusing primarily on the SBI for unhealthy drug use in adults, the NIDA’s guide incorporates all SBI guidelines—for alcohol, tobacco, and drugs—in one document (8). The 2012 policy by the AAFP (9) states that physicians should “include substance abuse prevention and patient education” and “diagnose substance abuse and addiction in the earliest stage possible, and treat or refer to treatment.” The AAFP guidelines specify that SBI for unhealthy alcohol and drug use should be conducted in primary care among adults as well as adolescents, with substance use to be strongly discouraged among the pregnant women because the “literature does not support any lower limit of substance use at which potential fetal harm is mitigated.”

Clinical Approach to the SBI Services in Primary Care Settings

The NIDA guide provides guidelines for the SBI delivery for alcohol, tobacco, and drugs in the general medical settings (8). The NIDA recommendations are consistent with the clinical guidelines for alcohol (16) and tobacco (19) SBI, as well as the Medicare and other insurance companies’ requirements for SBI coding and billing (13,14). Although this guide addresses all substances of abuse, its main focus is on the SBI services for unhealthy use of nonmedical prescription and illicit drugs among adults.

Existing guidelines recommend the Five A’s (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) approach for the SBI services:

■ Ask refers to screening and assessment of the risk level: “Screen, then intervene.” Intervention may then include all remaining “A’s” and is tailored to the screening results and determined risk level.

■ Advise indicates for a direct personal advice about substance use. The goal of the clinician’s advice is for the patients to hear clearly that a change in their behavior is recommended as based on medical concerns (review results with the patient), and to learn about their personal substance use and its effects on health (provide advice). Presentation of the facts in an objective way, using strong and personalized language, by a knowledgeable and trusted professional, has been shown to facilitate change.

■ Assess refers to evaluating the patient’s willingness (“readiness”) to change the unhealthy behavior (reduction of use or quitting), after hearing the clinician’s advice. If the patient is not willing to change his or her substance use, the clinician should restate the substance use–related health concerns, reaffirm a willingness to help when the patient is ready, and encourage the patient to reflect about perceived “benefits” of continued use versus decreasing or stopping use and barriers to change.

■ Assist involves helping the agreeable patient develop the treatment plan following the patient’s personal goals. Using behavior change techniques (e.g., motivational interviewing [MI]), the clinician should aid the patient in achieving agreed-upon goals and acquiring the appropriate skills, confidence, and social/environmental support. It is helpful if the plan describes in concrete terms the specific steps the patient elects to take to reduce/quit drinking, for example, the maximum number of drinks per day or week and how to prevent and manage high-risk situations or establish a support network. Starting with “small steps” while working toward a larger goal (abstinence or safe use) may be most reasonable and achievable for many patients.

Clinicians should also consider whether the patient would benefit from a medical treatment for addiction, such as detoxification or pharmacotherapy, or an additional assessment and therapy for potential comorbid physical or mental health problems. All sexually active patients with unhealthy alcohol or drug use—a risk factor for “risky behaviors”—should be counseled to practice safe sex and offered HIV and other sexually transmitted disease testing. Patients reporting any injection drug use should be encouraged to undergo HIV and hepatitis B/C testing if they have not had it twice over a 6-month period following the last injection.

■ Finally, Arrange refers to the consideration of a followup visit and specialty referrals. A follow-up appointment should be arranged for all patients who screened positive to provide ongoing assistance and adjust the treatment plan as needed. Optimally, all patients should also receive educational materials to take home.

All alcohol- or drug-dependent patients should be encouraged to see an addiction specialist. Unfortunately, many patients will decline, especially during this initial meeting, or not be able to successfully seek such services (too few treatment options, too far to the nearest center, incompatibility of treatment schedule with work hours, inadequate insurance coverage, etc.). However, almost regardless of geographical location, time of the day, or insurance coverage, many patients can, if they wish to do so, engage in mutual help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) or SMART Recovery. SAMHSA’s Treatment Facility Locator (http://findtreatment.samhsa.gov) and NIDA’s National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network List of Associated Community Treatment Programs (www.drugabuse.gov/CTN/ctps.html) can help find drug and alcohol treatment programs around the country. Primary care physicians can also complete a certification (through, e.g., an 8-hour Web-based training) in office-based buprenorphine maintenance therapy for opioid dependence to additionally assist selected patients (http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/howto.html).

Follow-up visits allow clinicians to offer a continued support for the patient. With patients who adhere to the set goals, clinicians should reinforce progress; renegotiate treatment goals, if indicated; and encourage regular follow-up. At each follow-up, patient progress should be documented (“Was the patient able to meet and sustain his goals?”). Former “at-risk users” and any patients about whom the clinician remains concerned should be rescreened annually. Those remaining moderate or high risk should be rescreened at the next appointment. Patients who are alcohol or drug dependent need careful close monitoring for follow-through with addiction treatment programs, self-help groups, coordination of care with specialists, and treatment of coexisting medical and mental health conditions. Patients who did not meet their treatment goals should be additionally supported; they should be praised for coming in and for courage to honestly report their situation. Clinicians should acknowledge that change is difficult; reemphasize willingness to help; readdress the impact of continued substance use; reevaluate the diagnosis, treatment goals, and plan; consider engaging significant others; and schedule close follow-up.

SBI for Unhealthy Substance Use (Alcohol, Drugs, Tobacco): Guidelines (8)

Unhealthy Substance Use Screening

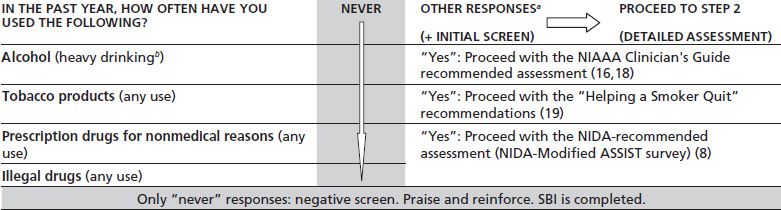

There are variety of screening tools and SBI implementation options that can be utilized for SBI for unhealthy substance, including drug, use in clinical practice. The NIDA-recommended approach is one of the possible choices. Following the NIDA algorithm, the initial screen, the so-called Quick Screen, represents Step 1 of SBI and consists of a single question about past-year substance use, adapted from the screening tool developed for adult primary care patients (Table 18-1) (20,21). Those answering “yes” to the initial screen (positive Quick Screen) should then receive an in-depth assessment (Step 2) to allow determination of the risk level (Step 3). Providing advice, and if needed a brief intervention (Step 4) will complete the SBI process.

TABLE 18-1 “ASK”: SINGLE-QUESTION INITIAL SCREEN FOR SUBSTANCE USE (NIDA QUICK SCREEN)

aPossible responses: “once or twice,” “monthly,” “weekly,” or “daily or almost daily.”

bHeavy drinking: five or more (for men) or four or more (for women) drinks in a day.

Negative Quick Screen (“never” response to all substances) does not require further, more detailed evaluation (see Table 18-1). Those with a negative screen (abstinence) should be praised, encouraged to continue healthy lifestyle choices, and rescreened annually (“It is really good to hear you aren’t using drugs. That is a very smart health choice”).

Positive Quick Screen warrants a more detailed evaluation though. In case of alcohol (“yes” to heavy drinking) or tobacco (“yes” to any tobacco use), the NIDA guide recommends proceeding with alcohol (16) or tobacco (19) SBI and provides links to the appropriate Web sites (see Table 18-1). Because any tobacco use places a patient at risk, all tobacco users should receive strong, unambiguous advice to quit (“Quitting tobacco is the most important thing you can do to protect your health”) (19).

Drug SBI (8)

Assessment of Severity: At-Risk Use, Abuse, or Dependence

(Note: in DSM-5, abuse and dependence will be combined and referred to as “disorder.”) According to the NIDA guidelines, those with a positive screen for drugs (“yes” to any use) should complete the NIDA-Modified ASSIST questionnaire (22), called NM-ASSIST, available as an interactive Web-based (www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist) or “full text” survey (www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf); the NIDA approach favors NM-ASSIST, but screening for and severity assessment of unhealthy drug use can be accomplished using other tools.

The eight-question NM-ASSIST inquires about the type of drugs, frequency of their use, and symptoms suggestive of abuse or dependence. Its total score, the so-called substance involvement score, determines the level of risk associated with illicit or nonmedical prescription drug use (0 to 3 points, lower; 4 to 26 points, moderate; and 27 + points, high risk). If more than one drug is reported, the patient receives a score for each substance endorsed (the NM-ASSIST questions are “repeated” for each reported drug), rather than a single cumulative score. Therefore, the patient’s risk level may differ from drug to drug. In addition to its “scored” questions, the NM-ASSIST also includes a question about injection drug use.

Clinicians should use clinical judgment to decide whether/when to deliver an intervention for drug use (especially if the risk level is assessed to be “lower”). The screen is only one indicator of a patient’s potential drug use problem. In case of an elevated “risk level” identified for more than one drug (substance), a decision about which substance to address first also needs to be clinically driven; in general, focusing intervention on the substance with the “highest risk” or the patient’s expressed greatest “motivation to change” may produce best results. Similarly, a cautious and clinically driven approach relates to the urine toxicology results, which represent only one of the multiple pieces of clinical puzzle; the NIDA guide has a separate appendix with the tips on biologic sample testing. Addition of biomarker testing, such as urine toxicology assays for drugs or serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin level for drinking, may be beneficial in selected patients (23).

Alcohol SBI for Adults (16,18)

Adult Alcohol Screening

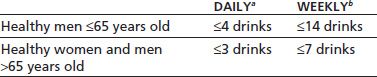

Consistent with the NIDA algorithm (described above), the NIAAA recommends a single question (see Table 18-1) about the presence of heavy drinking as an initial screen: “How many times in the past year have you had five or more (for men) or four or more (for women) drinks in a day?” An optional prescreening question about any alcohol use (“Do you sometimes drink beer, wine, or other alcoholic beverages?”) can help “ease” the patient into the more detailed screening should the patient answer “yes.” During this conversation, it is important to discuss with the patient what constitutes a single or “standard” drink (Table 18-2); presenting the patient with a chart of “standard drinks”—as the one available in the NIAAA’s Clinician’s Guide or online (www.RethinkingDrinking.niaaa.nih.gov)—can be very useful. This latter site can additionally help the patients screen themselves for unhealthy alcohol use.

TABLE 18-2 MAXIMUM (LOW-RISK) DRINKING LIMITS FOR ADULTS

One standard drink is equivalent to 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof spirits.

aExceeded daily limit: heavy drinking.

bExceeded daily or weekly limit: at-risk drinking.

With the endorsement of not drinking any alcohol or not engaging in any heavy drinking in the past year, the screen is negative and completed. Any heavy drinking in the past year constitutes a positive screen. Clinicians may decide though to recommend lower “drinking limits” or even abstinence for patients taking medications that may interact with alcohol (e.g., opioids), who engage in certain activities (e.g., driving), or who have a medical condition worsened by alcohol. For pregnant women, abstinence is the recommended healthiest choice.

Positive screen (heavy drinking or drinking above the clinician-recommended limits in the past year) warrants further inquiry about the alcohol use pattern and impact. At this point, we should determine the patient’s usual weekly alcohol consumption by asking questions about frequency and quantity (“On average, how many days a week do you have an alcoholic drink?” and “On a typical drinking day, how many drinks do you have?”). These two questions enable estimation of the number of drinks per week, which, if it exceeds weekly limits (see Table 18-2), increases concern and suspicion level for unhealthy alcohol use. All the gathered numbers should be recorded in the patient’s chart; they can be used later for a targeted counseling and to help monitor treatment progress.

Assessment of Severity in Adults: At-Risk Drinking, Abuse, or Dependence

Evaluation for AUDs as a part of a routine day-to-day clinical practice in primary care is often perceived as challenging. Available screening questionnaires as well as the chart in the NIAAA’s Clinician’s Guide can streamline this process. Patients who exceed recommended drinking limits or the questionnaire cutoffs but do not meet the criteria for AUDs are categorized as having “at-risk drinking,” which is a risk factor for the development of AUDs and other health consequences in the future.

Using the NIAAA guide’s chart, clinicians can determine the diagnosis of abuse versus dependence by “checking off” appropriate symptoms characteristic for a maladaptive pattern of alcohol use. The NIAAA chart is easy to use and not only can assist clinicians but may also be helpful for increasing the patient’s “buy-in,” a crucial element for treatment engagement; selected patients, when presented with this filled-out chart, can verify by themselves that they indeed meet criteria for an AUD. Distinguishing between “at-risk drinking,” abuse, and dependence is important and clinically relevant because it will determine appropriate clinical approach and treatment. Those classified as “at-risk drinkers” engage in “risky drinking” but do not endorse consequences. Those diagnosed with “abuse” experience drinking-related consequences, but without “dependence” or severe disorder. BI approach can be effective for nondependent drinkers; presence versus absence of drinking consequences will drive the content of BI conversation between clinician and the patient. Those diagnosed with dependence have severe consequences of drinking, meeting criteria for severe disorder. BI approach as “monotherapy” has not been shown to be particularly effective for dependent drinkers who should receive specialty treatment referral and/or pharmacotherapy, and be closely monitored.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was developed by the World Health Organization and is one of the most commonly used screening surveys to identify persons with unhealthy alcohol use (24). The original AUDIT is a 10-item questionnaire, available in the NIAAA guide (16), with three questions on the amount and frequency of drinking, three questions on alcohol dependence, and four on problems caused by alcohol, with a maximum total score of 40. Scores of ≥8 for men up to age 60 or ≥4 for women, adolescents, and men over 60 are considered positive screens, suggest strong likelihood of unhealthy alcohol consumption, and warrant more careful assessment; in the United States, using lower threshold scores (e.g., four to seven) for a positive screen in primary care settings may be more appropriate (25,26). The AUDIT’s score of 20 or greater suggests the presence of alcohol dependence. A shortened three-item version of the AUDIT, the so-called AUDIT-C, has also been shown an effective screening test for unhealthy alcohol use in primary care settings, with screening thresholds identified among men as scores ≥4 and among women as ≥3; a score of 7 or greater suggests alcohol dependence (25,27).

Alcohol Brief Intervention in Adults

Patients meeting criteria for unhealthy drinking qualify for a brief intervention. With the patient’s agreement, the clinician should provide, in an empathic and nonconfrontational manner, an objective assessment of drinking and its consequences (information about personal health harms, and possible benefits of cutting down or quitting) as well as clear, specific, and personalized behavior change advice: “You’re drinking more than what is medically safe. I strongly recommend that you cut down on drink.” “I believe that you have a serious alcohol problem and strongly recommend that you quit drinking.” “As your physician, I am willing to help you reduce or quit drinking.”

Abstinence can produce better treatment outcomes than drinking reduction in people with AUDs, especially dependence. Abstinence may also be recommended as a primary treatment goal for patients with specific comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions. However, for many people who should, but may not be willing to abstain, drinking reduction may be more acceptable. Even modest reduction in drinking can result in decreased alcohol-related harms. For some patients, cutting down from daily drinking to 3 days a week may be appropriate. For college students, cutting down from 12 to 15 drinks to 5 to 6 drinks on a weekend night may reduce the risk for significant harm and convince the student to begin the longer-term process of cutting back even further to lower the risk level.

SBI for Youth

Substance Use in Youth: General Considerations

In spite of the fact that the legal drinking age is 21 years in the United States, many youth start drinking earlier in life: One in three children had an alcoholic beverage by the end of 8th grade, with half of them reporting getting drunk (7,28,29). Drinking contributes to the top three causes of death among adolescents: unintentional injury (e.g., motor vehicle accidents), homicide, and suicide (30). Evidence shows that drinking at younger age increases the risk of developing addiction and alcohol-related harms, which include serious consequences such as death, injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and high-risk behaviors, as well as mental and physical health disorders. Mental health problems most likely to cooccur with AUDs include depression and suicide, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, schizophrenia, and bulimia disorders. Associated physical health conditions include trauma sequelae, sleep, eating or gastrointestinal problems, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or unintended pregnancy, and liver enzyme abnormalities.

Patterns of substance use in the community have influence on the youth’s substance use. Permissive parental attitudes toward substance use and having friends or family members who use alcohol, tobacco, or drugs are strong predictors of substance use by youth. Parental monitoring and presence of clear household rules about substance use are protecting factors against the youth’s substance use (7,28,29).

Although the guidelines by the USPSTF state that existing evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for unhealthy substance use in youth, new research lends support for effectiveness of SBI for adolescents (31–33), and most professional organizations, including the AAP, the AAFP, the NIAAA, the NIDA, and the NQF, recommend implementing SBI in youth.

In 2011, the NIAAA, in collaboration with the AAP, released a guide for practitioners describing the rationale for and an approach to alcohol SBI for youth (7,17). According to this guide, all children and youth between ages 9 and 18 years should be screened for alcohol use as part of an annual examination or acute care visit or when seeing patients who

■ Have not been seen recently

■ Are likely to drink (e.g., tobacco users)

■ Have mental health problems known to cooccur with substance abuse

■ Have physical health conditions that might be alcohol related

■ Engage in high-risk behaviors (e.g., have STIs or are pregnant)

■ Show substantial negative behavioral changes

Confidentiality and Parental Involvement

Screening minors for substance use and related disorders inevitably brings to light the issue of confidentiality and parental involvement. Setting up the stage in advance for the scope and extent of confidentiality is very helpful. Optimally, clinicians would share with the patient and the parents all the details about confidentiality policies and disclosure provisions in advance, best starting at 7- or 8-year-old well-child visits, or at least prior to the screening. With all adolescent substance users, the clinician should inquire about parental awareness, and seek the patient’s permission to speak to the parents (or guardians) or, at least, encourage the patient to discuss substance use with the parents.

In general, the discussion about and treatment for the minor’s substance use or abuse can usually be kept confidential if the minor wishes to do so; preserving confidentiality may help strengthen the trust and treatment alliance between the clinician and the minor. Although most medical organizations and laws support the ability of clinicians to provide confidential care for minors in relation to substance use, it is important to be aware of specific laws governing each state. Information about minor consent laws can be obtained from the state medical societies or the Center for Adolescent Health and the Law (www.cahl.org).

There are circumstances, though, when a clinician should consider breaking confidentiality and engage the parents to ensure safety, for example, the presence of “acute danger signs” (see below in assessment of severity in youth), a need for referral for further treatment, or negative health consequences related to substance use. The NIAAA guide also suggests engaging parents, even against the minor’s wishes, for any alcohol use by elementary school kids, alcohol-related mild problems in middle school, or significant problems in high school students. In general, the clinicians should apply their best medical judgment, together with the state’s laws, to decide whether breaking confidentiality is warranted. Confidentiality can be unintentionally compromised if, for example, the diagnostic codes that may reveal the nature of the adolescent’s problems are included in “explanation of benefits” sent to parents by the insurance company or when a follow-up visit is scheduled for “substance abuse”; these aspects of care require a consideration in advance (e.g., a follow-up visit may be labeled as for immunizations, acne follow-up).

Alcohol Screening in Youth

Practitioners should strive to establish good rapport with adolescent patients and encourage honest answers. Building in alone time (without parents) during the visit and explaining confidentiality policies (see above) can facilitate it. Explaining the purpose of asking about sensitive issues can further promote a trusting relationship and alleviate the youth’s perception of being singled out (“My goal is to help my patients healthy and that’s why I talk to all my patients about alcohol use and other health risks”).

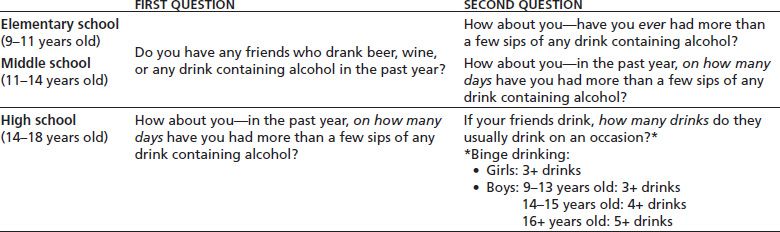

The NIAAA guide recommends using two screening questions about the past-year alcohol use to facilitate stratification of the child’s drinking behavior into a lowest-, moderate-, or highest-risk category. The choice of initial questions depends on the child’s school level and age (Table 18-3). For elementary and middle school kids, the first screening question is about their friends’ alcohol use (any use), and the second question is about the patient’s personal alcohol use. For high school students, the first screening question is about the patient’s personal alcohol use frequency in the past year, and the second question asks about friends’ binge drinking. Presence of friends who drink among younger kids or friends who binge drink among high school students has been shown to increase the patient’s risk of unhealthy substance use and should trigger additional probing questions.

TABLE 18-3 TWO-QUESTION INITIAL SCREEN: ASK ABOUT PERSONAL ALCOHOL USE AND FRIENDS’ DRINKING

Assessment of Severity in Youth: At-Risk Drinking, Abuse, or Dependence

Youth who do not drink (negative screen) should be praised and counseled on the continuation of their healthy behaviors. It is helpful to elicit and affirm their reasons for not drinking and educate about risks associated with drinking. Jointly with the clinician, they should also explore plans on how to continue staying alcohol-free when friends drink and be advised never to ride in a car with a driver who used alcohol or drugs. Nondrinkers with nondrinking friends should be rescreened at least yearly. However, those with drinking friends should be rescreened more frequently, best during the next visit.

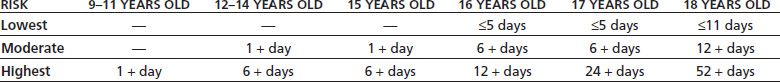

All drinking youth should be evaluated in more depth to assess and stratify risk (Table 18-4). Any past-year drinking places an elementary school student in a high risk and a child 12 to 15 years old (middle or early high school) in a moderate-risk category. Moderate- and highest-risk patients should be additionally evaluated for the presence of AUDs. Additional questionnaires, asking in more detail about alcohol consumption and related problems, can assist this process.

TABLE 18-4 ADOLESCENTS WHO REPORT DRINKING IN THE PAST YEAR: RISK STRATIFICATION BY AGE AND THE NUMBER OF PAST-YEAR DRINKING DAYS

Elementary school: 9–11 years old; middle school: 11–14 years old; high school: 14–18 years old.

Substance Use Surveys for Youth

For drinking youth, several brief questionnaires to help assess in more depth and gauge risk of the adolescent’s substance use are available. They can identify problems that can then be discussed during MI and intervention. Although the AUDIT can be used in drinking adolescents, with lower thresholds for identifying unhealthy alcohol use than in adults (24,34), its focus is on alcohol only. The CRAFFT (35), on the other hand, is an easy-to-use, validated, and reliable six-question survey, inquiring about both alcohol and drug use in several contexts (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble). It is endorsed by the NIDA and the AAP and can discriminate between substance use, at-risk use, and disorder in adolescents (36). It can be prefaced with the phrase “in the past year” and administered in verbal, electronic, or paper–pencil format. Positive responses to two or three of the CRAFFT questions raise suspicion for a substance use problem that warrants further inquiry, while four or more “yes” responses suggest substance dependence. Full text of the survey is available online (7).

Recently, a couple of brief tools have also shown promise as initial screening tools for unhealthy alcohol or cannabis use among young people (12 to 21 years old) in the ED (37). Positive screen results identify youth at risk for having an alcohol or cannabis use disorder who should receive a more detailed assessment, most likely on the outpatient basis. A two-question instrument, derived from DSM-IV criteria, may provide a “Quick Screen” in the ED to detect probable unhealthy alcohol use (“In the past year, have you sometimes been under the influence of alcohol in situations where you could have caused an accident or gotten hurt?” and “Have there often been times when you had a lot more to drink than you intended to have?”) (38). Youth answering “yes” to one or both of the “DSM-IV screen” questions have an eight times higher risk of having an AUD. Youth who report cannabis use more than two times over the previous year on a one-question screen for unhealthy cannabis use (Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, DISC) (39) have an almost sevenfold risk of having a cannabis use disorder compared to those who used cannabis less frequently (“In the past year, how often have you used cannabis [0 to 1 time; >2 times]?”). In general, it is worth noting that many available screening instruments aim at identifying substance use disorder; for most (if not all) youth, any use, and especially at-risk use, should be inquired about and approached seriously.

Just as with adults, it is important to clarify what a “single” drink means while inquiring about alcohol quantity. Charts defining “standard” drink equivalents are very useful. Incorporating “what else I know” about the patient into the risk assessment and then intervention can strengthen and personalize treatment; for example, family history of substance use disorders, permissive environment at home toward substance use, or low parental involvement would heighten concern about the degree of risk.

Alcohol Brief Intervention in Youth

All drinking youth should receive BI, with BI principles similar to those as for adults. Lowest- and moderate-risk patients without an AUD should be advised to stop (or at least reduce) drinking and receive counseling similar to that described above for the nondrinking youth (but appropriately “beefed-up”).

Highest-risk patients and those with an AUD should receive brief MI. For these patients, a referral to addiction medicine should always be considered. In addition, adolescents who display “acute danger signs” will need immediate intervention and, likely, parental or guardian involvement that may require breaking of the minor’s confidentiality. The most common and potentially lethal acute danger signs include driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs; high-amount intake (e.g., prior poisoning or overdose); combining alcohol with drugs, especially sedatives; engaging in high-risk behaviors in relation to substance use (e.g., unprotected sex, injuries due to risks taken); signs of AUD; or injection drug use.

Follow-up is crucial for the success of attaining treatment goals by both adults and youth (40). Negotiating the timing of follow-up with the patient as well as scheduling it for additional reasons (e.g., acne) may increase the likelihood that the patient keeps that appointment. As with adults, the starting point of the follow-up evaluation is to ask the patient if he or she was able to meet and sustain goals, prior to the reassessment and risk restratification. Treatment goals and plans should be revised as appropriate and as based on the newly obtained information and the patient’s preferences.

CURRENT EVIDENCE ON SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: A BRIEF SUMMARY

Screening and Brief Intervention for Unhealthy Alcohol Use

Brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use is one of the most clinically effective and cost-effective preventive services from among services recommended by the USPSTF, with economic savings similar to screening for colorectal cancer, hypertension, or visual acuity (adults older than 64 years) and to influenza or pneumococcal immunization (41).

In contrast to those other services, screening and counseling for unhealthy alcohol use are currently delivered at much lower rates, with only a minority of problem drinkers in a national survey reporting having been asked and counseled about their alcohol use (42,43).

Cost–benefit studies have demonstrated savings of $30,000 to $40,000 for each $10,000 invested in the health care system for SBI (10). In a primary care setting, SBI can reduce alcohol use and at-risk drinking by 10% to 30% during a 12-month follow-up (44–46), with one study reporting maintenance of improved drinking patterns for 48 months (10,47). All adults in primary care should be screened for unhealthy alcohol use (2). A number of barriers can impede SBI implementation in the clinical settings; adequate resources, staff training, and the nonstigmatizing, nonstereotyping identification of those at risk are the main facilitators of SBI in primary care (48).

In trauma settings, SBI seems to reduce drinking, drinking-related harms, and recurrence of injuries requiring ED care or hospital admissions among injured at-risk drinkers (5,49–53). However, the overall evidence is not as strong as for a primary care setting. In the ED settings, research suggests that SBI can reduce drinking and result in fewer subsequent ED visits among at-risk drinkers (54–56). Emergency medical professionals are encouraged to incorporate SBIRT into clinical ED practice (56,57) though some high-methodological-quality studies in ED settings have yielded negative results (58,59). In general inpatient medical settings, evidence on the effectiveness of opportunistic alcohol SBI is inconclusive and suggests that SBI may be beneficial (60–64), but does not work as well as for primary care, trauma, or ED patients. One of the key issues in this setting is that the vast majority of general medical inpatients, identified as “positive” by screening, have alcohol dependence. BIs have less proven success for decreasing drinking or linking alcohol-dependent patients with addiction-specific treatment after hospital discharge. Patients in the ED or inpatient settings usually accept participation in alcohol screening and interventions (65). More details on the SBI services in the trauma, hospital, and ED settings are provided in separate sidebars.

Limited evidence suggests that SBI can reduce morbidity and mortality in the population of problem drinkers (64,66). SBI appears to work in adults (10,66–68), including young adults ages 18 to 25 (69) and older adults ages 65 and older (70,71), college students (72–74), pregnant women, and women of child-bearing age (47,75), though in the latter, the evidence is not as strong. According to the USPSTF guidelines, there is still insufficient evidence on alcohol SBI efficacy in adolescents; however, the growing evidence is encouraging, and main professional organizations and expert panels advise conducting SBI in youth at least annually, starting at age 9 years (6,7,9,28,32,33).

Although a single, short 5- to 15-minute intervention may be helpful, a multiple-contact BI, usually including one to three booster sessions, have been shown to be effective and are recommended (2,44,45). The optimal interval for SBI is unknown. Patients with past alcohol-related problems, young adults, and other high-risk groups (e.g., smokers) may benefit from frequent screening and, if indicated, BI (2).

The counseling style of effective BIs is based on MI and commonly includes elements such as empathy, feedback, advice with an emphasis on patient responsibility and self-efficacy, and a treatment plan with a menu of options (76,77). The BI studies with the largest effect sizes utilized primary care clinicians to deliver the intervention (10,68,78–80). There has been a growing support and evidence for efficacy for different ways of SBI delivery (e.g., via e-mail, phone, texting, or Web-based, rather than in person) that may be particularly useful for groups less likely to access traditional services, such as women, young people (especially students), and at-risk users (81–83).

Screening and Brief Intervention for Unhealthy Drug Use

Based on the nearly complete absence of randomized trials, especially in primary care settings, the USPSTF concluded that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening of adolescents, adults, and pregnant women for unhealthy drug use (4). However, many professional organizations recommend universal SBI for drug misuse in general medical settings, with NIDA providing a detailed guide for clinicians (8).

Overall, very limited research has evaluated the efficacy of SBI for unhealthy prescription-based and illicit drug use (85). There is some indication that SBI may be beneficial for cocaine and heroin use (84). Humeniuk et al. (85) found no effect in the United States and overall very small differences in opioid use in India.

Overall, there is little evidence of harm reduction associated with either screening for illicit drug use or behavioral interventions used in the treatment of abuse or dependence (4). There is fair evidence that people who reduce or stop drug use have a lower risk of negative health outcomes (4).

SBI for Prescription Opioid Misuse

Research designed to develop screening methods for the detection of prescription opioid abuse or dependence has been growing. Most studies have focused on survey-based screening for aberrant, drug-related behaviors and toxicology screens. A recent study found that four aberrant behaviors were strongly associated with opioid dependence (86); these included early refills, feeling intoxicated, self-increasing dose, and oversedating oneself. Unfortunately, no screening tool has been validated for universal screening in primary care for prescription drug abuse. NIDA recommends the NIDA-Modified ASSIST questionnaire (22) (described above) for prescription drug abuse screening. The four-question modified CAGE survey (87) (felt the need to cut down, annoyed when someone suggested to cut down, felt guilty about use, and used first things in the morning to calm down) can also be implemented, as described in the SAMHSA’s screening tools (www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/CAGEAID.pdf). While there is limited information on the sensitivity and specificity of routine toxicology drug screening in opioid-treated chronic pain patients in primary care settings, however, this has become a routine practice in many settings.

There is no current strong literature on the efficacy of SBI for prescription opioid abuse or dependence. Although not considered traditional BI, treatment contracts for prescription opioids often incorporate many of the basic BI principles including a client-centered agreement to minimize or stop alcohol and illicit drug use and obtaining these medications from other physicians.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSES OF SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTIONS FOR UNHEALTHY ALCOHOL USE

The following papers, among others, were used to support the summary statements in the previous sections. What follows is a brief overview of SBI-related research for unhealthy alcohol use and illicit drug use/disorders.

A systematic review by Jonas et al. (46), published in 2012 as a summary of evidence for the USPSTF, evaluated the benefits and harms of SBI for unhealthy drinking among adolescents and adults. The 23 included trials generally focused on nondependent drinkers. The best evidence for efficacy was for brief (10- to 15-minute) multicontact BIs. This review found a moderate strength of evidence supporting BI efficacy for drinking reduction among nondependent adults as well as young adults or college students who engage in unhealthy drinking. Compared to controls, adults with unhealthy drinking reduced their consumption by 3.6 drinks per week (10 trials, 4,332 participants), with 12% fewer adults reporting heavy drinking (7 trials, 2,737 participants) and 11% more adults reporting drinking below the recommended limit (9 trials, 5,973 participants) over 12 months. Among young adults and college students, BI also resulted in decreased alcohol use (1.7 fewer drinks per week; 3 trials, 1,421 participants) and heavy drinking (0.9 fewer heavy drinking days per month; 3 trials, 1,448 participants). The review did not find sufficient evidence to draw conclusions about SBI efficacy for pregnant women, adolescents, and alcohol-dependent adults or for the reduction in injuries, accidents, or alcohol-related liver problems among adult “unhealthy drinkers.” In general, little or no evidence of SBI harms was found.

A prior systematic review, prepared by Whitlock et al. (44), for the USPSTF, focused on the efficacy of SBI to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among adults in primary care settings, arriving at similar conclusions as the above, newer review. Whitlock et al.’s review included 12 controlled trials. At 6- to 12-month follow-up, brief, multicontact BIs (up to 15 minutes of initial contact and at least one booster session) resulted in drinking reduction by 2.9 to 8.7 drinks per week (13% to 34% net reductions, respectively) more than in controls, and the proportion of participants drinking at moderate or safe levels was 10% to 19% greater as compared to controls. One study reported the maintenance of an improved drinking pattern for 48 months (10). Very brief (<5 minutes) or brief (up to 15 minutes) single-contact interventions were less effective or ineffective in reducing at-risk or harmful drinking but were better than no intervention. No adverse effects of SBI were noted. The review concluded that brief multicontact BI can provide an effective component of a public health approach to reducing at-risk or harmful alcohol use among adult primary care patients.

Solberg et al. conducted a meta-analysis of primary care studies and evaluated the clinically preventable burden (CPB) and cost-effectiveness of SBI implementation and compared these values across other (2) recommended preventive services (41). The CPB was calculated as the product of effectiveness times the alcohol-attributable fraction of both mortality and morbidity (measured in quality-adjusted life years, or QALYs). Cost-effectiveness from both the societal perspective and the health system perspective was estimated. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 10) and cost-effectiveness studies were included. The mean percentage of SBI effectiveness for both heavy drinking and hazardous drinking in primary care was found to be 17.4% (range, 9.8% to 30.1%), reflecting behavior change at 6 months to 2 years after intervention. The calculated CPB was 176,000 QALYs saved over the lifetime of a birth cohort of 4,000,000 people. From both the societal and health system perspectives, SBI is cost effective and may be cost saving. This meta-analysis suggests SBI as one of the highest-ranking preventive services among the 25 effective services evaluated using standardized methods. As current levels of delivery are the lowest of comparably ranked services, SBI deserves special attention by clinicians and care delivery systems for improvement.

A meta-analysis was conducted by the Cochrane Group, led by Kaner et al. (45), to evaluate the effectiveness of SBI to reduce alcohol consumption among nontreatment-seeking patients in primary care settings, including EDs. The meta-analysis included 21 RCTs (n = 7,286 participants), showing robust results that participants receiving SBI significantly reduced their alcohol consumption as compared to the control group (mean difference, −41 g/wk or 4 to 5 units), with substantial heterogeneity noted between trials. The percentage of heavy drinkers and binge drinkers was significantly reduced in the SBI as compared to the control group. The analysis confirmed the benefit of SBI in men (significant mean difference, −57 g/wk) studied was relatively small (nonsignificant mean difference, −10 g/wk; n = 499 women). When compared with brief BI, extended BI was associated with an insignificantly greater reduction in alcohol consumption (mean difference = −28 g/wk) and with a trend to an increased reduction in alcohol use of 1.1 g/wk and for each extra minute of treatment exposure (p = 0.06). Reduction of drinking was also observed in some control groups. Mean loss to follow-up was 27%, with more subjects lost in the SBI than control group (significant 3% difference). The results of this meta-analysis are broadly similar to previous work focused on primary care samples (88–90) and showed that SBI consistently produced reductions in alcohol consumption. The effect was clear in men at 1 year of follow-up but unproven in women.

The systematic review by Saitz (91) evaluated efficacy of alcohol SBI in primary care, with the main focus on effects for those with very heavy alcohol use or dependence. The review identified 16 RCTs (n = 6,839 patients). However, only two of these RCTs did not exclude patients based on very heavy drinking or dependence. One of these studies, in which 35% of 175 Mexican American patients (mostly men) had dependence, found no difference in drinks per week or severity scores between groups, and the other, in which 58% of 24 women with dependence, showed no difference in alcohol consumption between groups. Findings of this review highlight the absence of evidence and the need for further research on SBI efficacy in primary care patients with alcohol dependence or very heavy drinking.

The systematic review and meta-analysis by Bertholet et al. (90) evaluated the efficacy of SBI aimed at reducing long-term alcohol use and related harms in the nontreatment-seeking individuals in primary care settings. Nineteen RCTs (n = 5,639 subjects) were analyzed. The BIs in the studies ranged from 5 to 45 minutes per session (mostly 5 to 15 minutes), and the majority included booster sessions. The control groups received either brief advice (up to 5 minutes) or “usual care” or no intervention. The adjusted, intention-to-treat analysis showed a significant mean pooled difference of −38 g/wk of ethanol (approximately 4 standard drinks) in favor of the SBI group. Most of the effective interventions lasted 5 to 15 minutes and included written handouts. Reduction in alcohol consumption at 6 months was comparable to that at 12 months, and comparable between men and women. Intervention modality (type of provider, session duration, use of the MI technique, presence of booster sessions) did not play a significant role. No negative effects of SBI were reported. Evidence of efficacy for other outcome measures was inconclusive. Based on this meta-analysis, SBI appears effective in reducing alcohol consumption at 6 and 12 months among nontreatment-seeking primary care patients, regardless of gender.

The meta-analysis by Ballesteros et al. (89) assessed gender-specific effects of alcohol BI in primary care settings. Seven studies (n = 2,981 subjects) with a follow-up of 6 to 12 months were included. The effect sizes of BI for the reduction of alcohol consumption were statistically significant and similar for men (0.25) and women (0.26). The odds ratios (OR) for drinking below hazardous levels at 6 to 12 months were also similar (OR = 2.3 for both men and women; p < 0.05). This analysis supports the similarity of outcomes among men and women achieved by BI for hazardous drinking in primary care settings.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Beich et al. (92) evaluated the effectiveness of screening, as a part of a SBI program, for excessive alcohol use in general practice. The eight included studies used health questionnaires for screening, and the BIs included feedback, information, and advice. In 1,000 screened patients, 90 screened positive and required further assessment, after which 25 qualified for BI. After 1 year, 2.6 reported they drank less than the maximum recommended level. Although SBI can reduce excessive drinking, screening in general practice may be inefficient as a precursor to BIs targeting excessive alcohol use. This meta-analysis raised questions about the feasibility of screening in general practice for excessive alcohol use. Although the authors reported efficacy of the BI data, the findings should be interpreted with caution, as this study was not designed primarily to evaluate the efficacy of BI but rather to assess potential effectiveness of the screening process.

A meta-analysis by Poikolainen (88) evaluated the effectiveness of BIs to reduce drinking in primary care settings. It included 14 RCTs with follow-up time at 6 to 12 months. Significant heterogeneity was observed when data on very brief BIs among men and women were pooled (which is consistent with the findings of the meta-analysis of Bertholet et al. (90)). For brief BIs (5 to 20 minutes), the change in alcohol consumption was not significant among men or women. For extended BIs (several visits), the pooled effect estimate of change in alcohol intake was −51 g of alcohol per week among women. Among men, the estimate was of similar magnitude, but lack of homogeneity was noted. In sum, extended BIs were effective among women but not men. Other BIs seemed to be effective sometimes but not always, and the average effect could not be reliably estimated.

A meta-analysis by Wilk et al. (93) assessed the effectiveness of BIs in primary care heavy or problem drinkers. Twelve RCTs (n = 3,948) were included. The BI sessions lasted for up to 1 hour and incorporated simple MI techniques. The pooled OR (1.9; p < 0.05) was in favor of BIs over no intervention, and was consistent across gender and the intensity of intervention. Compared to no-intervention controls, heavy drinkers who received a BI were almost twice as likely to moderate their drinking at 6 to 12 months.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Rubak et al. (40) evaluated the effectiveness of MI-based interventions in different conditions, including alcohol consumption, and the factors potentially influencing treatment outcomes. Seventy-two RCTs were included. When using MI in brief encounters of 15 minutes, 64% of the studies showed an effect. More than one encounter with the patient increased the MI effectiveness. Meta-analysis showed a significant effect of MI for standard ethanol content (n = 648 subjects) and blood alcohol concentration (n = 278 subjects). This report indicates that MI-based BIs can reduce alcohol consumption as evaluated by standard ethanol content and blood alcohol concentration.

The meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al. (66) evaluated effects of BIs on mortality in problem drinkers. Among the included 32 studies (n = 7,521 subjects), 6 reported unverified deaths, and 4 reported verified mortality status. The total number of deaths was relatively low. The pooled relative risk (RR) of dying was approximately 0.5 (p < 0.05). The prevented fraction of deaths was about 0.3, indicating that about one in every three deaths can be prevented by the intervention. The number needed to treat (NNT) ranged from 154 to 317. In the studies with verified mortality status, the NNT was 282, indicating that 282 subjects have to be treated in order to prevent one death. Based on the limited evidence from secondary analyses, BIs appear to reduce mortality by about 23% to 36% in the population of problem drinkers.

A meta-analysis by Moyer et al. (94) assessed efficacy of BI for alcohol problems in the treatment-seeking and nontreatment-seeking (“opportunistic”) samples. Fifty-six studies were included. Most studies of the treatment-seeking samples compared BI to extended treatments (n = 20); most studies of the opportunistic samples compared BI to a control condition (n = 34). In the nontreatment-seeking samples, BI tended to be briefer and delivered by general health care professionals, whereas BI in the treatment-seeking samples were usually more intensive and delivered by therapists or counselors. In the treatment-seeking samples, no substantial differences were found between the efficacies of brief compared to extend BIs. In the opportunistic samples, compared to controls, small to medium aggregate effect sizes in favor of BI emerged across different followup points; the most pronounced effect size for alcohol consumption (0.67) and all drinking-related outcomes (0.3) was noted at the earliest follow-up (no more than 3 months), and the least pronounced and statistically nonsignificant effect size (0.12 to 0.20) was found at follow-up longer than 12 months, suggesting dissipation of the BI effects over time. Larger effect of BI compared to a control condition was also noted when individuals with more severe alcohol problems were excluded. In a small number of studies reporting outcomes by gender, BI efficacy did not differ between men and women. This meta-analysis indicates that BI is efficacious for drinking reduction; however, its effects may fade over time. The BI efficacy was increased when dependent drinkers were excluded. Brief and extended BIs show similar efficacy.

A systematic review by the Cochrane Group, led by Dinh-Zarr, assessed the effect of interventions intended to reduce alcohol consumption or prevent injuries or their antecedents among “problem drinkers” in diverse settings (95). Seventeen RCTs were included. Among those, seven evaluated BIs in the clinical setting. BIs were associated with a significant reduction of injury-related deaths (RR = 0.65) and showed beneficial effects on diverse nonfatal injury–related outcomes. Interventions, including BIs, for problem drinking appear to reduce injuries and their antecedents.

INDIVIDUAL STUDIES OF SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION FOR UNHEALTHY ALCOHOL USE

Primary Care Settings

SBI is efficacious for alcohol misuse and recommended in primary care settings. Implementation of SBI in primary care settings can allow for a better integration of medical care and substance abuse treatment. Such an integrated approach may benefit individuals with substance abuse–related medical conditions and be cost-effective compared to a “treatment-as-usual model,” in which primary care and substance abuse treatment are provided separately (96).

Project TrEAT and Project Health are examples of the positive SBI trials in primary care. Project TrEAT was the first US study to evaluate long-term efficacy and cost–benefit of SBI among 774 at-risk drinkers in primary care (10,67,68). After two short BI sessions delivered by a clinician, each followed by a phone call, at-risk adult drinkers who received BI significantly decreased alcohol use, health resource utilization, and alcohol-related costs compared to controls. These effects were observed at 6 months and maintained during a 48-month follow-up.

In Project Health, after a very short BI, delivered by a clinician as part of a routine primary care visit, participants significantly reduced drinking and were less likely to relapse to at-risk drinking than controls at 6 and 12 months (79,80). Only one study evaluated efficacy of SBI over a period greater than 4 years (97). After up to three sessions of BI, delivered over a 6-month period, 554 at-risk and harmful drinkers in the BI group significantly reduced their drinking at 9 months compared to “no-treatment” controls. The differences between the groups dissipated at 10-year follow-up; however, at 10 years, both the BI and control groups tended to drink less than at baseline or at 9 months, which suggests “assessment effects” or a favorable natural history of risky alcohol use.

Results of more recent studies, by Kaner et al. (98) and Hilbink et al. (99), are less optimistic. The “SIPS” trial, conducted by Kaner et al. (98), compared efficacy of different BI strategies for reducing unhealthy drinking among adult primary care patients. Primary care practices in England were randomized to one of the three study conditions: control (simple feedback and a written information leaflet on unhealthy drinking), brief advice group (as controls plus a 5-minute structured brief advice, delivered by a trained research associate), or brief counseling group (as brief advice group plus a delayed, 20-minute counseling, delivered by an alcohol counselor). Among 2,991 eligible patients, 900 (30%) screened positive for unhealthy drinking (AUDIT score ≥8), and 756 were enrolled. At 6 and 12 months, although all groups improved compared to baseline, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the proportions of those with a negative AUDIT score. Although the counseling group reported increased “readiness to change” and higher satisfaction with the BI process, no additional differences between the BI groups and the control group were found in alcohol-related problems or quality of life. The authors concluded that the results do not support the additional delivery of brief advice or counseling over the simple feedback with a written information leaflet. It is worth noting though that the study did not exclude patients with AUDIT scores suggesting alcohol dependence for whom SBI is of unclear efficacy. In addition, although almost all participants received a leaflet/brief advice (as appropriate), only 57% of relevant participants returned for counseling; this could have affected the results and suggested that scheduling a separate visit to provide an intervention may not be an optimal approach.

Hilbink et al. (99) conducted an RCT evaluating effects of a multifaceted intervention in primary care aimed at the reduction of unhealthy drinking. Physician practices in the Netherlands were randomized to control condition (unhealthy drinkers were mailed the guidelines and information letters about unhealthy drinking) or the “improvement intervention.” The intervention included the entire clinical practice team who received short training in SBI, thus facilitating changes on the organizational and staff awareness and skill level, with emphasis on educating clinicians; unhealthy drinkers in these practices received a personalized feedback letter with a suggestion to discuss drinking further with their clinician. Among 6,318 screened, 712 patients from 70 practices scored positive for unhealthy nondependent drinking (AUDIT score 8 to 19). Over the course of 2 years, a large proportion (41.6%) of unhealthy drinkers reduced drinking to a low-risk level; however, a significantly larger reduction was demonstrated in the control (47%) than the intervention (35.5%) group. Although certain patient characteristics were associated with drinking reduction (e.g., older age, female sex, attitudes toward drinking), characteristics of the practices were not predictive of decreased alcohol use. The authors drew conclusions that “the intervention has been counterproductive” and hypothesized that these unexpected results or, rather, lack of favorable results of the clinic-based intervention may be related to the overall low level of engagement of the participating clinicians.

Adolescents and Young Adults

Research on SBI efficacy for adolescent unhealthy drinking is limited, but its results are encouraging. The USPSTF evaluated it as insufficient to recommend for or against universal screening of adolescents in primary care. However, other professional organizations advise such a screening based on promising early evidence on alcohol SBI efficacy in this vulnerable population. Data indicate that rates of adolescent alcohol use range from 5% among general ED admissions to nearly 50% among trauma admissions, and alcohol use by adolescents is associated with increases in severity of injury and cost of medical treatment (100).

A 2012 published systematic review by Yuma-Guerrero et al. (31) focused on the efficacy of alcohol SBI in adolescents in acute care settings. The review identified seven RCTs evaluating SBI effects on alcohol consumption and/ or consequences among 3,309 risky drinkers, aged 12 to 24 years, all patients in the EDs of the level I trauma centers. All but one study used MI-based interventions. These studies produced overall promising but inconsistent results. The authors concluded the evidence is not sufficient at this point to provide an unambiguous support for the SBI efficacy for adolescent ED patients who engage in risky drinking. The Yuma-Guerrero et al.’s review included the following RCTs of the ED patients: Monti et al. (101) evaluated adolescents aged 18 to 19 years (n = 94) who either tested positive (blood alcohol level) for or self-reported alcohol use. Although both the intervention and control groups reduced their drinking at 3 and 6 months, no significant differences between the groups were found in alcohol consumption. Compared to controls, the intervention group was less likely to experience negative consequences of drinking at 6 months (p < 0.05) though. Johnston et al. (102) examined effects of SBI among 12- to 20-year-old adolescents (n = 631) receiving ED care for injury. At 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments, both the intervention and the control groups reduced prevalence of risky behaviors, but there were no significant differences between the groups on alcohol-related outcomes (driving after drinking, riding with an impaired driver, or binge drinking). Spirito et al. (103) evaluated outcomes of a single BI session in the ED setting among 13- to 17-year-old adolescents (n = 152) admitted for an alcohol-related injury. Over 12 months, both intervention and control groups significantly reduced number of drinks per occasion; the groups did not differ on alcohol-related outcomes. However, the subgroup of adolescents with problematic alcohol use (almost 50% of the sample) significantly more reduced frequency of drinking and high-volume drinking if they received intervention (p < 0.01), indicating that BIs had some efficacy, particularly for adolescents engaging in the most risky drinking behavior. Maio et al. (104) compared effects of an interactive computer program–based intervention versus standard of care among 14- to 18-year-old ED patients (n = 655). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups on main outcomes. Both groups showed a reduction in alcohol misuse and binge drinking at 3 months, but these levels returned to baseline at 12 months. Interestingly, within the subgroups of adolescents, who reported either riding with an intoxicated driver or “drinking and driving” at baseline, those in the intervention group showed greater improvement in alcohol misuse compared to controls. Monti et al. (105) evaluated efficacy of SBI among 18- to 24-year-olds (n = 198) presenting to the ED for an alcohol-related event. The experimental group received an intervention session in the ED and then telephone booster sessions at 1 and 3 months. Both intervention and control groups significantly reduced alcohol consumption at 6- and 12-month assessments, with the intervention group displaying larger reductions compared to controls (p < 0.01). There were no differences between groups in alcohol-related injuries or moving violations. In a three-arm RCT, Walton et al. (106) examined the efficacy of SBI (therapist or computer delivered vs. a control condition) among 726 adolescents aged 14 to 18 years who screened positive for both alcohol use and aggression. Compared to controls, participants in the therapist-delivered BI group reported reduced occurrence of peer aggression and violence, and violence consequences at 3 months (p < 0.05). Participants in both BI groups decreased their reported alcohol consequences at 6 months (p < 0.05). Given that violence is one of the top causes of mortality and morbidity in adolescents, the reduction in severe violence following a single-session BI is important (NNT = 8: eight at-risk adolescents would need to receive the therapist-delivered BI to prevent one episode of severe peer aggression). Bernstein et al. (107) evaluated effects of peer educator–delivered intervention among 14-to 21-year-old pediatric ED patients (n = 853) as compared to the standard assessment control group; in addition, a third, minimal assessment control group (screening survey only at baseline) was added to adjust for the effect of assessment reactivity on control group behavior (three-arm RCT design). Compared to the standard assessment group, the BI group was more likely to report efforts to quit drinking and being careful about situations when drinking at 3 months and 12 months (p < 0.05). Although alcohol consumption declined in both groups over time, there were no significant between-group differences in consumption or alcohol-related consequences or risk behaviors.

A meta-analytic review by Jensen et al. (32) assessed effectiveness of MI-based BI for adolescent substance use. Among 21 identified controlled trials of BIs, including 5,471 adolescents aged 12 to 23 years recruited primarily from the community settings, most addressed alcohol (n = 12) and marijuana (n = 12), then multiple restricted substances (n = 9), tobacco (n = 7), and various street drugs (n = 6). Meta-analysis revealed statistically homogeneous sample of effect sizes, with an overall small but significant mean posttreatment effect size of the MI interventions that was retained over time. The MI interventions appeared effective across a variety of substance use behaviors, varying BI session lengths, and different settings, thus providing a strong support for the effectiveness of MI interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change.

A review by Tevyaw and Monti (76) presented the use and efficacy of motivational enhancement and other brief interventions for substance use, particularly drinking, in adolescents and young adults. This review found that positive results demonstrated in clinical trials using motivational enhancement interventions with adolescents and college students primarily stem from reductions in alcohol-related problems and, to a lesser extent, from reductions in drinking. Although most young people do mature out of hazardous drinking patterns, motivational enhancement–based interventions may help accelerate that maturation process in high-risk individuals. The review concluded that motivational enhancement–based BIs can decrease alcohol-related negative consequences, reduce alcohol use, and increase treatment engagement among adolescents and young adults.

Grossberg et al. (69), as a part of Project TrEAT (68), examined 226 primary care at-risk drinkers aged 18 to 30 years. Young adults who received the BI significantly reduced drinking had fewer ED visits, motor vehicle crashes and events, and fewer arrests for controlled substance or liquor violation over the 4-year follow-up. SBIs seem feasible and accepted by young adults (108).

Older Adults

SBIs seem effective for older adults. Project GOAL, conducted in parallel to Project TrEAT (68) and based on similar methodology, showed that SBI can decrease alcohol use among older primary care at-risk drinkers during the 2-year follow-up (70,71).

College Students

About 40% of college students report binge drinking in the prior 2 weeks (109); a third meet criteria for alcohol abuse and 6% for alcohol dependence in the prior year (35). SBIs seem effective for reducing at-risk drinking in college students in general (72,73), in mandated college students, and in students admitted to the ED (110,111). College students seem receptive to alcohol SBIs (72,73).

While there are a limited number of SBI studies conducted in health care settings, there is a very robust set of studies testing counselor-delivered brief intervention. The best known of these studies was conducted by Marlatt et al. (72) and Baer et al. (73). This study included 461 college freshmen, identified as at-risk drinkers or a “normative control” group during their final high school year. At-risk drinkers were randomized into the “no-treatment” control arm or the BI arm, which received one to two BI sessions, delivered by psychologists, with a personalized feedback letter. Over 4 years, at-risk students, in both intervention and control groups, significantly reduced drinking and related harmful consequences, with changes significantly favoring the BI group. These long-term benefits occurred even in the context of maturational, natural trends, observed in the “normative control” group.