Patient Story

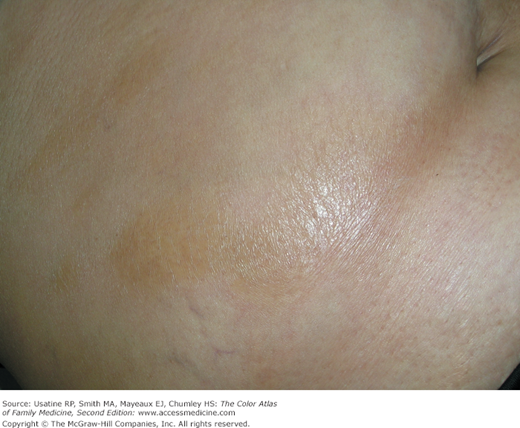

A 35-year-old woman presented with areas of shiny tough skin in patches over her abdomen (Figure 182-1). The patient was otherwise in good health and was puzzled by this new condition. She feared that all her skin would become this way. The skin was slightly uncomfortable but not painful. A 3-mm punch biopsy confirmed the clinical suspicion of morphea or localized scleroderma. The patient was treated with topical clobetasol and calcipotriol with some improvement in skin quality and symptoms. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was positive, but she has not developed progressive systemic sclerosis.

Introduction

Epidemiology

- The prevalence rates of diseases that share scleroderma as a clinical feature are reported ranging from 4 to 253 cases per 1 million individuals.1

- Systemic sclerosis has an annual incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 The peak onset is between the ages of 30 and 50 years.1

- In the United States, the incidence of morphea has been estimated at 25 cases per 1 million individuals per year.1

- Worldwide, there are higher rates in the United States and Australia than in Japan or Europe.2

- Pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension are the leading causes of death as a consequence of these diseases.3

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- The scleroderma disorders can be subdivided into three groups: localized scleroderma (morphea; Figures 182-1, 182-2, and 182-3), systemic sclerosis (Figures 182-4, 182-5, 182-6, 182-7, 182-8, and 182-9), and other scleroderma-like disorders that are marked by the presence of thickened, sclerotic skin lesions.

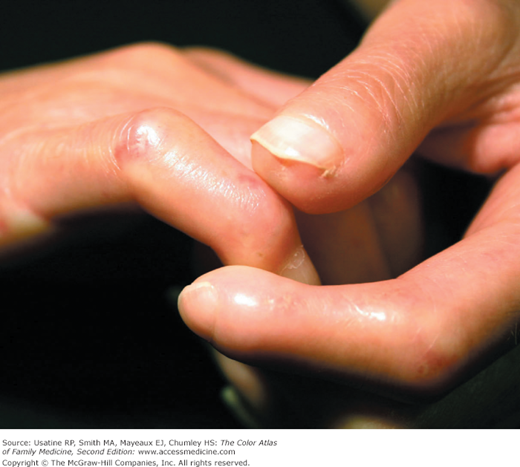

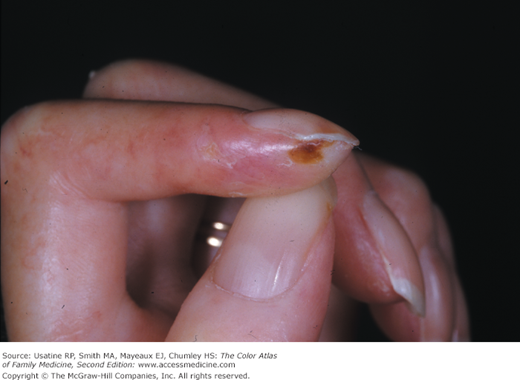

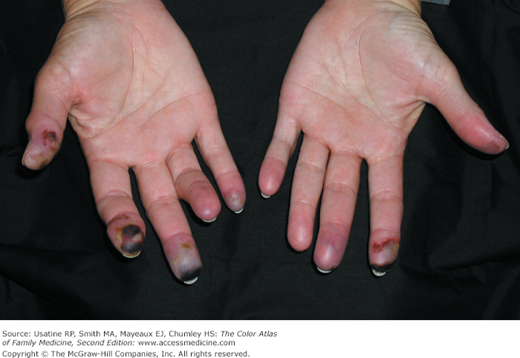

- The most common vascular dysfunction associated with scleroderma is Raynaud phenomenon (Figure 182-10). Raynaud phenomenon is produced by arterial constriction in the digits. The characteristic color changes progress from white pallor, to blue (acrocyanosis), to finally red (reperfusion hyperemia). Raynaud phenomenon generally precedes other disease manifestations, sometimes by years. Many patients develop progressive structural changes in their small blood vessels, which permanently impair blood flow, and can result in digital ulceration or infarction. Other forms of vascular injury include pulmonary artery hypertension, renal crisis, and gastric antral vascular ectasia.

- Systemic sclerosis is used to describe a systemic disease characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse (DcSSc) or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis [LcSSc]).

- Patients with LcSSc usually have skin sclerosis restricted to the hands and, to a lesser extent, the face and neck. With time, some patients develop scleroderma of the distal forearm. They often display the CREST syndrome, which presents with Raynaud phenomenon (Figure 182-10), esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly (Figures 182-4, 182-5, 182-6, and 182-7), telangiectasias (Figures 182-8 and 182-9), and calcinosis cutis (Figure 182-11).

- Patients with DcSSc often present with sclerotic skin on the chest, abdomen, or upper arms and shoulders. The skin may take on a “salt-and-pepper” look (Figure 182-12). They are more likely to develop internal organ damage caused by ischemic injury and fibrosis than those with LcSSc or morphea.

- Almost 90% of patients with systemic sclerosis have some GI involvement,4 although half of these patients may be asymptomatic. Any part of the GI tract may be involved. Potential signs and symptoms include dysphagia, choking, heartburn, cough after swallowing, bloating, constipation and/or diarrhea, pseudoobstruction, malabsorption, and fecal incontinency. Chronic gastroesophageal reflux and recurrent episodes of aspiration may contribute to the development of interstitial lung disease. Vascular ectasia in the stomach (often referred to as “water-melon stomach” on endoscopy) is common, and may lead to GI bleeding and anemia.

- Pulmonary involvement is seen in more than 70% of patients, usually presenting as dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. Fine “Velcro” rales may be heard at the lung bases with lung auscultation. Pulmonary vascular disease occurs in 10% to 40% of patients with systemic sclerosis, and is more common in patients with limited cutaneous disease. The risk of lung cancer is increased approximately 5-fold in patients with scleroderma.

- Autopsy data suggest that 60% to 80% of patients with DcSSc have evidence of kidney damage.5 Some degree of proteinuria, a mild elevation in the plasma creatinine concentration, and/or hypertension are observed in as many as 50% of patients.6 Severe renal disease develops in 10% to 15% of patients, most commonly in patients with DcSSc.

- Symptomatic pericarditis occurs in 7% to 20% of patients, which has a 5-year mortality rate of 75%.7 Primary cardiac involvement includes pericarditis, pericardial effusion, myocardial fibrosis, heart failure, myocarditis associated with myositis, conduction disturbances, and arrhythmias.8 Patchy myocardial fibrosis is characteristic of systemic sclerosis, and is thought to result from recurrent vasospasm of small vessels. Arrhythmias are common and are most caused by fibrosis of the conduction system.

- Pulmonary vascular disease occurs in 10% to 40% of patients with scleroderma, and is more common in patients with limited cutaneous disease. It may occur in the absence of significant interstitial lung disease, generally a late complication, and is usually progressive. Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, sometimes with pulmonale and right-sided heart failure or thrombosis of the pulmonary vessels may develop.

- Joint pain, immobility and contractures may develop, with contractures of the fingers being most common (Figure 182-6). Neuropathies and central nervous system involvement, including headache, seizures, stroke, vascular disease, radiculopathy, and myelopathy, occur.

- Scleroderma produces sexual dysfunction in men and women. In men, it is very frequently associated with erectile dysfunction.

Figure 182-7

Scleroderma on the patient in Figure 182-6 showing leg involvement with muscle atrophy. (Courtesy of Jeffrey Meffert, MD.)

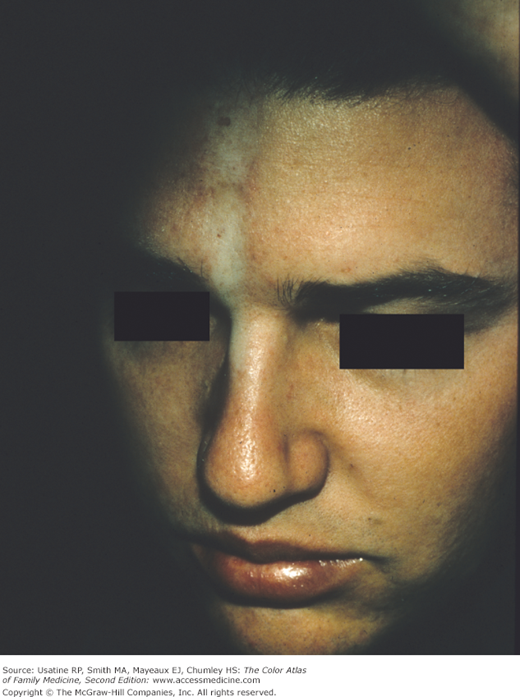

Figure 182-9

Telangiectasias on the face of the patient in Figure 182-8. (Courtesy of Everett Allen, MD.)