Schizophrenia

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Although multiple neurotransmitter dysfunctions are involved in schizophrenia, the etiology is more likely mediated by multiple subcellular processes that are influenced by different genetic polymorphisms.

Although multiple neurotransmitter dysfunctions are involved in schizophrenia, the etiology is more likely mediated by multiple subcellular processes that are influenced by different genetic polymorphisms.

![]() The clinical presentation of schizophrenia is characterized by positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and impairment in cognitive functioning.

The clinical presentation of schizophrenia is characterized by positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and impairment in cognitive functioning.

![]() Comprehensive care for individuals with schizophrenia must occur in the context of a multidisciplinary mental healthcare environment that offers comprehensive psychosocial services in addition to psychotropic medication management.

Comprehensive care for individuals with schizophrenia must occur in the context of a multidisciplinary mental healthcare environment that offers comprehensive psychosocial services in addition to psychotropic medication management.

![]() A thorough patient evaluation (e.g., history, mental status examination, physical examination, psychiatric diagnostic interview, and laboratory analysis) should occur to establish a diagnosis of schizophrenia and to identify potential co-occurring disorders, including substance abuse and general medical disorders.

A thorough patient evaluation (e.g., history, mental status examination, physical examination, psychiatric diagnostic interview, and laboratory analysis) should occur to establish a diagnosis of schizophrenia and to identify potential co-occurring disorders, including substance abuse and general medical disorders.

![]() Given that it is challenging to differentiate among antipsychotics based on efficacy, side effect profiles become important in choosing an antipsychotic for an individual patient.

Given that it is challenging to differentiate among antipsychotics based on efficacy, side effect profiles become important in choosing an antipsychotic for an individual patient.

![]() Pharmacotherapy guidelines should emphasize monotherapies with antipsychotics of optimal efficacy-to-side effect ratios and progress to medications with greater side effect risks, and combination regimens should only be used in the most treatment-resistant patients.

Pharmacotherapy guidelines should emphasize monotherapies with antipsychotics of optimal efficacy-to-side effect ratios and progress to medications with greater side effect risks, and combination regimens should only be used in the most treatment-resistant patients.

![]() Adequate time on a given medication at a therapeutic dose is the most important variable in predicting medication response.

Adequate time on a given medication at a therapeutic dose is the most important variable in predicting medication response.

![]() Long-term maintenance antipsychotic treatment is necessary for the vast majority of patients with schizophrenia in order to prevent relapse.

Long-term maintenance antipsychotic treatment is necessary for the vast majority of patients with schizophrenia in order to prevent relapse.

![]() Thorough patient and family psychoeducation should be implemented, and methods such as motivational interviewing that focus on patient-driven outcomes that allow patients to achieve life goals should be employed.

Thorough patient and family psychoeducation should be implemented, and methods such as motivational interviewing that focus on patient-driven outcomes that allow patients to achieve life goals should be employed.

![]() Pharmacotherapy decisions should be guided by systematic monitoring of patient symptoms, preferably with the use of brief symptom rating scales and systematic assessment of potential adverse effects.

Pharmacotherapy decisions should be guided by systematic monitoring of patient symptoms, preferably with the use of brief symptom rating scales and systematic assessment of potential adverse effects.

Schizophrenia is one of the most complex and challenging of psychiatric disorders. It represents a heterogeneous syndrome of disorganized and bizarre thoughts, delusions, hallucinations, inappropriate affect, and impaired psychosocial functioning. From the time that Kraepelin first described dementia praecox in 1896 until publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) in 2000, the description of this illness has continuously evolved.1 Scientific advances that increase our knowledge of CNS physiology, pathophysiology, and genetics will likely improve our understanding of schizophrenia in the future.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

According to the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study, the lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia using strict diagnostic criteria ranges from 0.6% to 1.9%. If a broader definition is used, the lifetime rate rises to 2% to 3%.2 The worldwide prevalence of schizophrenia is remarkably similar among most cultures. Schizophrenia most commonly has its onset in late adolescence or early adulthood and rarely occurs before adolescence or after the age of 40 years. Although the prevalence of schizophrenia is equal in males and females, the onset of illness tends to be earlier in males. Males most frequently have their first episode during their early 20s, whereas with females it is usually during their late 20s to early 30s.1,3

ETIOLOGY

Although the etiology of schizophrenia is unknown, research has demonstrated various abnormalities in brain structure and function.4 However, these changes are not consistent among all individuals with schizophrenia. The cause of schizophrenia is likely multifactorial, that is, multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities can play a role in producing the similar but varying clinical phenotypes we refer to as schizophrenia.

A neurodevelopmental model has been evoked as one possible explanation for the etiology of schizophrenia.4 This model proposes that schizophrenia has its origins in some as yet unknown in utero disturbance, possibly occurring during the second trimester of pregnancy. Evidence for this is provided by the abnormal neuronal migration demonstrated in studies of schizophrenic brains. This “schizophrenic lesion” can result in abnormalities in cell shape, position, symmetry, connectivity, and functionally to the development of abnormal brain circuits.4 Changes are consistent with a cell migration abnormality during the second trimester of pregnancy, and some studies associate upper respiratory infections during the second trimester of pregnancy with a higher incidence of schizophrenia.5 Other studies associate low birth weight (LBW; less than 2.5 kg [5.5 lb]), obstetric complications, or neonatal hypoxia with schizophrenia.2 Maternal stress, perhaps related to the effects of circulating glucocorticoids in utero, may be a risk factor for schizophrenia. Maternal “stress” could derive from a variety of external and internal noxious events (malnutrition, infection, etc.). The resulting secondary “synaptic disorganization” associated with such insults is thought not to produce overt clinical manifestations of psychosis until adolescence or early adulthood because this is the corresponding time period of neuronal maturation.

Although studies have shown decreased cortical thickness and increased ventricular size in the brains of many patients with schizophrenia, this occurs in the absence of widespread gliosis.4 One hypothesis is that obstetric complications and hypoxia, in combination with a genetic predisposition, could activate a glutamatergic cascade that results in increased neuronal pruning. It is hypothesized that this genetic predisposition may be related to genes controlling N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity. As a part of the normal neurodevelopmental process, pruning of dendrites occurs. In normal individuals, approximately 35% of the peak number of dendrites at 2 years of age are pruned by midadolescence. Some studies have shown a higher percentage of pruning in individuals with schizophrenia. Furthermore, synaptic pruning predominantly involves glutamatergic dendrites. Hypoxia or other prenatal insult can result in a decreased number of basal neurons from which to start, and glutamatergic activation can exaggerate the pruning process.4,5 There is also renewed interest in the immune system and schizophrenia. Studies have shown an increased susceptibility to immune/autoimmune disorders in schizophrenia, as well as abnormalities of autoantibodies and cytokine functioning.6 The immune hypothesis of schizophrenia also emphasizes integration of mental and physical well-being.

Numerous studies have shown neuropsychological abnormalities and impairment in reaching normal motor milestones and abnormal movements in young children who later develop schizophrenia.3 Abnormalities in brain function occur long before the onset of psychotic symptomatology and provide empirical evidence for schizophrenia being a neurodevelopmental disorder.4 However, the progressive clinical deterioration in many patients suggests that this illness can also have a neurodegenerative component. This is consistent with recent brain imaging studies that show deteriorative brain changes in patients with frequent relapses.2,4,7 These changes may be most pronounced among adolescents with early onset schizophrenia.8 Schizophrenia may be an illness exhibiting neurodegenerative propensity based on a vulnerable neurodevelopmental predisposition.2,9,10 Although a specific abnormality has not been discovered, evidence suggests a genetic basis for schizophrenia. Although the risk of developing schizophrenia is 0.6% to 1.9% in the U.S. population, the risk is approximately 10% if a first-degree relative has the illness and 3% if a second-degree relative has the illness.2,11 If both parents have schizophrenia, the risk of producing an offspring with schizophrenia increases to approximately 40%. Twin studies in dizygotic twins report that the risk of the second twin developing schizophrenia if one twin has the illness is between 12% and 14%. However, in monozygotic twins the risk increases to 48%.11 Numerous adoption studies indicate that the risk for schizophrenia lies with the biologic parents, and change in the environment during the child’s developmental stages does not alter this. If schizophrenia occurs in siblings, the onset of illness tends to occur at the same age in each, thus lessening the possibility of an environmental precipitant.

Numerous approaches have been utilized to study the genetics of schizophrenia, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), copy number variant (CNV) studies, and gene candidate studies.12 Genetic etiologies in schizophrenia are likely heterogeneous, but present with similar clinical phenotypes, and involve epigenetic interactions.12 GWAS have identified nearly 20 genetic loci that reach genome-wide significance (P = 5 × 10–8), but only some of these have been replicated in multiple studies.13 GWAS indicate susceptible genes for schizophrenia on chromosome 6, and common genes underlying psychosis on ZNF804A, CACN1A2, NRGN, and PBRM1.12 Risk for schizophrenia has been demonstrated in CNV studies for deletions on chromosomes 1, 15, and 22. Polymorphism in the VAL/MET alleles of the catecholamine-O-methyl transferase gene may explain some of the frontal lobe functional deficits in a subset of individuals with schizophrenia.11 Other recent studies have shown abnormalities in several genes that code for neurodevelopment and for trophic factors.11,14 For example, dysbindin is a neurodevelopmental protein gene that is found on chromosome 6, and it has been termed a NMDA-related schizophrenia susceptibility gene.15 Alleles associated with decreased dysbindin RNA in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex have been reported in patients with schizophrenia and their families.15 Another recent GWAS of a large pedigree showed increased signal at chromosome 8p, close to the gene that encodes for neuregulin—another neurodevelopmental gene. Interest is burgeoning regarding how genetic vulnerability might interact with environmental stressors, such as cannabis abuse.16

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Advances in imaging technology and changes in research methodology have resulted in varying results from brain imagining studies over time, although most recent studies have found decreases in gray matter and increases in ventricular size. A recent meta-analysis of systematic reviews conducted since the year 2000 found consistent decreases in gray matter in multiple brain areas, including the frontal lobes, cingulate gyri, and medial temporal regions among others. A corresponding increase in ventricular size was also observed as well as decreased white matter in the corpus callosum.17 Changes in hippocampal volume may correspond with impairment in neuropsychological testing.2 Rather than a decrease in the number of neurons in affected brain areas, a decrease in axonal and dendritic communications between cells can result in a loss of connectivity that can be important with respect to neuronal adaptivity and CNS homeostasis.2,4 These changes are likely consistent with the evidence for abnormal neuronal pruning.4 Four dopaminergic pathways and five major dopamine (DA) receptor subtypes are of primary interest. Table 50-1 outlines the origin, innervation, and primary functional activity of each pathway, as well as the effects of DA antagonists.18

TABLE 50-1 Dopaminergic Tracts and Effects of Dopamine Antagonists

Evidence supports the presence of a DA-receptor defect in schizophrenia. Numerous positron emission tomography (PET) studies have shown regional brain abnormalities, including increased glucose metabolism in the caudate nucleus and decreased blood flow and glucose metabolism in the frontal lobe and left temporal lobe.3 This can indicate dopaminergic hyperactivity in the head of the caudate nucleus and dopaminergic hypofunction in the frontotemporal regions. PET studies using dopamine-2 (D2)-specific ligands suggest increased densities of D2 receptors in the head of the caudate nucleus with decreased densities in the prefrontal cortex.3,4 However, a recent meta-analysis showed an increase in presynaptic DA synthesis and release in the striatum with only a small increase in D2/3 receptor availability.19 PET studies assessing dopamine-1 (D1) function suggest that subpopulations of schizophrenics may have decreased densities of D1 receptors in the caudate nucleus and the prefrontal cortex. Hypofrontality can be associated with lack of volition and cognitive dysfunction, core features of schizophrenia. It is unknown whether these changes represent a primary event or secondary processes related to other pathophysiologic abnormalities in schizophrenia. Because of the heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of schizophrenia, it has been suggested that the DA hypothesis may be more applicable to “neuroleptic-responsive psychosis,” with multiple different etiologies possibly being responsible for causing schizophrenia.2 Attempts have been made to develop relationships between these abnormal findings and behavioral symptoms present in schizophrenic patients. The positive symptoms are possibly more closely associated with DA-receptor hyperactivity in the mesocaudate, whereas negative symptoms and cognitive impairment are most closely related to DA-receptor hypofunction in the prefrontal cortex. Presynaptic D1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex are thought to be involved in modulating glutamatergic activity, and this can be important with regard to working memory in individuals with schizophrenia.2

The glutamatergic system is one of the most widespread excitatory neurotransmitter systems in the brain. Alterations in its function, either hypoactivity or hyperactivity, can result in toxic neuronal reactions.3 Dopaminergic innervation from the ventral striatum decreases the limbic system’s inhibitory activity (perhaps through γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA] interneurons); thus, dopaminergic stimulation increases arousal. The corticostriatal glutamate pathways have the opposite effect, inhibiting dopaminergic function from the ventral striatum, therefore allowing the limbic system to have increased inhibitory activity. Descending glutamatergic tracts interact with dopaminergic tracts directly as well as through GABA interneurons. Glutamatergic deficiency produces symptoms similar to those of dopaminergic hyperactivity and possibly those seen in schizophrenia. Clinical support for this comes from the fact that phencyclidine, a potent psychotomimetic, is a noncompetitive antagonist at the NMDA receptor, a major glutamate receptor. Similarly, abuse of ketamine, a veterinary anesthetic, can resemble schizophrenia. Ketamine, a competitive antagonist at glutamatergic NMDA receptors, has been shown to lead to reduction in D1 neurotransmission through glutamatergic inhibition of DA release.20 It is proposed that schizophrenia may involve some in utero assault that leads to a developmental defect in NMDA receptor function—so-called NMDA hypofunction. This defect is proposed to have latent clinical expression with the psychotic manifestations from NMDA hypofunction not being seen until late adolescence or early adulthood. MicroRNAs, small noncoding RNAs, are critical to neurodevelopment as well as to regulation of adult neuronal processes. NMDA-regulated microRNA miR-132 is significantly downregulated in individuals with schizophrenia as compared with controls. Several genes are regulated by miR-132, and this altered expression may be related to NMDA hypofunction and the abnormal synaptic pruning seen in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia.21

Serotoninergic receptors are present on dopaminergic axons, and stimulation of these receptors decreases DA release, at least in the striatum.22 Although somewhat more diffuse, the distribution of serotonergic neurons is similar to that of dopaminergic neurons, thus allowing these two neurotransmitter systems to innervate the same areas. In fact, 5-hydroxytryptamine2 (serotonin-2; 5-HT2) receptors and D4 receptors have been found to be colocalized in the cortex.2,22 Patients with schizophrenia with abnormal brain scans have higher whole-blood serotonin (5-HT) concentrations, and these concentrations are correlated with increased ventricular size.22

![]() Schizophrenia is a complex disorder, and multiple etiologies likely exist. Based on current knowledge, it is naive to think that any currently proposed etiology can adequately explain the genesis of this complex disease. Molecular research involving genetically determined subtle changes in microRNA, G proteins, protein metabolism, and other subcellular processes can eventually identify the biologic disturbances associated with schizophrenia.2,4,9,21

Schizophrenia is a complex disorder, and multiple etiologies likely exist. Based on current knowledge, it is naive to think that any currently proposed etiology can adequately explain the genesis of this complex disease. Molecular research involving genetically determined subtle changes in microRNA, G proteins, protein metabolism, and other subcellular processes can eventually identify the biologic disturbances associated with schizophrenia.2,4,9,21

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Schizophrenia is the most common functional psychosis, and great variability occurs in clinical presentation. Despite numerous attempts to portray a stereotype in movies and on television, the stereotypic schizophrenic essentially does not exist. Moreover, schizophrenia is not a “split personality.” It is a chronic disorder of thought and affect with the individual having a significant disturbance in interpersonal relationships and ability to function in society.

The first psychotic episode can be sudden in onset with few premorbid symptoms, or commonly can be preceded by withdrawn, suspicious, peculiar behavior (schizoid). During acute psychotic episodes, the patient loses touch with reality, and in a sense, the brain creates a false reality to replace it. Acute psychotic symptoms can include hallucinations (especially hearing voices), delusions (fixed false beliefs), and ideas of influence (beliefs that one’s actions are controlled by external influences). Thought processes are disconnected (loose associations), the patient may not be able to carry on logical conversation (alogia), and can have simultaneous contradictory thoughts (ambivalence). The patient’s affect can be flat (no emotional expression), or it can be inappropriate and labile. The patient is often withdrawn and inwardly directed (autism). Uncooperativeness, hostility, and verbal or physical aggression can be seen because of the patient’s misperception of reality. Self-care skills are impaired, and the patient is frequently dirty and unkempt, and in general has poor hygiene. Sleep and appetite are often disturbed. When the acute psychotic episode remits, the patient typically has residual features. This is an important point in differentiating schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders. Although residual symptoms and their severity vary, patients can have difficulty with anxiety management, suspiciousness, and lack of volition, motivation, insight, and judgment. Therefore, they often have difficulty living independently in the community. Because of poor anxiety management and suspiciousness, they are frequently withdrawn socially, and have difficulty forming close relationships with others. In addition, impaired volition and motivation contribute to poor self-care skills and make it difficult for the patient with schizophrenia to maintain employment.

Patients with schizophrenia frequently experience a lack of historicity, or difficulty in learning from their experiences. They can repeatedly make the same mistakes in social conduct and situations requiring judgment. They have difficulty understanding the importance of treatment, including medications, in maintaining their ability to function in society. Therefore, they tend to discontinue medications and other treatments, and this increases the risk of relapse and rehospitalization. The co-occurrence of substance abuse (predominantly alcohol or polysubstance—alcohol, cannabis, cocaine) in patients with schizophrenia is very common and is another frequent reason for relapse and hospitalization.1,2 This effect can be caused by direct toxic effects of these drugs on the brain,23 but is also caused by the medication nonadherence that is associated with substance abuse.

Although the course of schizophrenia is variable, the long-term prognosis for many patients is poor. It is marked by intermittent acute psychotic episodes and impaired psychosocial functioning between acute episodes, with most of the deterioration in psychosocial functioning occurring within 5 years after the first psychotic episode.23 By late life, the patient can appear “burned out,” that is, the patient ceases to have acute psychotic episodes, but residual symptoms persist. In a subpopulation of patients, probably 5% to 15%, psychotic symptoms are nearly continuous, and response to antipsychotics is poor.23

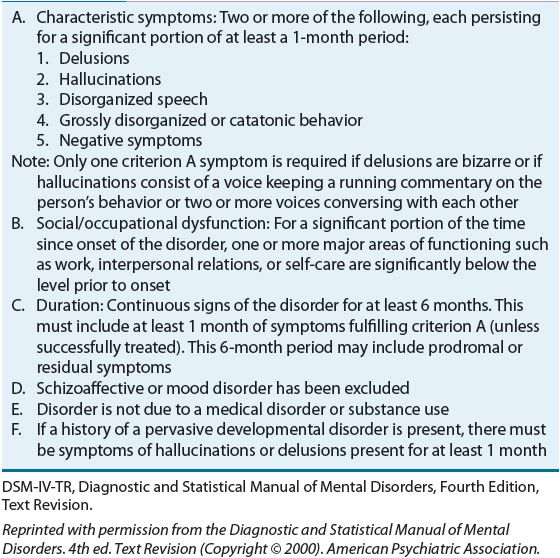

Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder, and the patient’s history must be carefully assessed for dysfunction that has persisted for longer than 6 months. After their first episode, patients with schizophrenia rarely have a level of adaptive functioning as high as before the onset of the disorder. Table 50-2 summarizes the DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia.1

TABLE 50-2 DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Schizophrenia

![]() The DSM-IV-TR classifies the symptoms of schizophrenia into two categories: positive and negative. Recently greater emphasis has been placed on a third symptom category, cognitive dysfunction (Table 50-3).23 The areas of cognition found to be abnormal in schizophrenia include attention, working memory, and executive function. Positive symptoms have traditionally attracted the most attention and are the ones most improved by antipsychotics. However, negative symptoms and impairment in cognition are more closely associated with poor psychosocial function. Along with these characteristic features of schizophrenia, many patients also have comorbid psychiatric and general medical disorders.23 These include depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and general medical disorders such as respiratory disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and metabolic disturbances. These comorbidities substantially complicate the clinical presentation and course of schizophrenia.

The DSM-IV-TR classifies the symptoms of schizophrenia into two categories: positive and negative. Recently greater emphasis has been placed on a third symptom category, cognitive dysfunction (Table 50-3).23 The areas of cognition found to be abnormal in schizophrenia include attention, working memory, and executive function. Positive symptoms have traditionally attracted the most attention and are the ones most improved by antipsychotics. However, negative symptoms and impairment in cognition are more closely associated with poor psychosocial function. Along with these characteristic features of schizophrenia, many patients also have comorbid psychiatric and general medical disorders.23 These include depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and general medical disorders such as respiratory disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and metabolic disturbances. These comorbidities substantially complicate the clinical presentation and course of schizophrenia.

TABLE 50-3 Schizophrenia Symptom Clusters

It has been suggested that symptom complexes can correlate with prognosis, cognitive functioning, structural abnormalities in the brain, and response to antipsychotic drugs. Negative symptoms and cognitive impairment can be more closely associated with prefrontal lobe dysfunction and positive symptoms with temporolimbic abnormalities. Many patients demonstrate both positive and negative symptoms. Patients with negative symptoms frequently have more antecedent cognitive dysfunction, poor premorbid adjustment, low level of educational achievement, and a poorer overall prognosis.23

TREATMENT

Desired Outcome

Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment in schizophrenia, and it is impossible in most patients to implement effective psychosocial rehabilitation programs in the absence of antipsychotic treatment.23 ![]() A pharmacotherapeutic treatment plan should be developed that delineates drug-related aspects of therapy. Most deterioration in psychosocial functioning occurs during the first 5 years after the initial psychotic episode, and treatment should be particularly assertive during this period.23 The individualized treatment plan created for each patient should have explicit end points defined, including realistic goals for the target symptoms most likely to respond, and the relative time course for response.23,24 Other desired outcomes include avoiding unwanted side effects, integrating the patient back into the community, increasing adaptive functioning to the extent possible, and preventing relapse.

A pharmacotherapeutic treatment plan should be developed that delineates drug-related aspects of therapy. Most deterioration in psychosocial functioning occurs during the first 5 years after the initial psychotic episode, and treatment should be particularly assertive during this period.23 The individualized treatment plan created for each patient should have explicit end points defined, including realistic goals for the target symptoms most likely to respond, and the relative time course for response.23,24 Other desired outcomes include avoiding unwanted side effects, integrating the patient back into the community, increasing adaptive functioning to the extent possible, and preventing relapse.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Psychosocial rehabilitation programs oriented toward improving patients’ adaptive functioning are the mainstay of nondrug treatment for schizophrenia. These programs can include case management, psychoeducation, targeted cognitive therapy, basic living skills, social skills training, basic education, work programs, supported housing, and financial support. In particular, programs aimed at employment and housing have been the more effective interventions and are considered “best practices.” Programs that involve families in the care and life of the patient have been shown to decrease rehospitalization and improve functioning in the community. For particularly low-functioning patients, assertive intervention programs, referred to as active community treatment (ACT), are effective in improving patients’ functional outcomes. ACT teams are available on a 24-hour basis and work in the patient’s home and place of employment to provide comprehensive treatment, including medication, crisis intervention, daily living skills, and supported employment and housing.23,24 Medication treatment cannot be successful without proper attention to these other aspects of care. People with schizophrenia need comprehensive care, with coordination of services across psychiatric, addiction, medical, social, and rehabilitative services. The level of coordination in the United States is often insufficient, and patients become at risk to “fall through the cracks.” National policy documents have called for greater coordination of care.25 Additionally, emphasis is growing on the role that the patient plays in a recovery-based system of care, where the person’s lifetime aspirations and goals become the center of care, rather than symptom reduction being the primary focus. This recovery-based approach recognizes the strengths and resilience of people with schizophrenia.26 It also acknowledges how people with schizophrenia can also be a support to others who are coping with the illness.27 It is important to frame clinical decision making in the context of a mutual process involving patient and clinician—rather than a unilateral “here’s a prescription … please take these tablets” approach. It is increasingly recognized that cognitive behavioral therapy can help some patients. A list of psychotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of schizophrenia is given in Table 50-4.

TABLE 50-4 Psychotherapeutic Approaches to the Treatment of Schizophrenia

Pharmacologic Therapy

![]() The importance of initial accurate diagnostic assessment cannot be overemphasized. A thorough mental status examination (MSE), psychiatric diagnostic interview, physical and neurologic examination, complete family and social history, and laboratory workup must be performed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude general medical or substance-induced causes of psychosis. Laboratory tests, biologic markers, and commonly available brain imaging techniques do not assist in the diagnosis of schizophrenia or selection of medication. A pretreatment patient workup not only is important in excluding other pathology but also serves as a baseline for monitoring potential medication-related side effects, and should include vital signs, complete blood count, electrolytes, hepatic function, renal function, electrocardiogram (ECG), fasting serum glucose, serum lipids, thyroid function, and urine drug screen.

The importance of initial accurate diagnostic assessment cannot be overemphasized. A thorough mental status examination (MSE), psychiatric diagnostic interview, physical and neurologic examination, complete family and social history, and laboratory workup must be performed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude general medical or substance-induced causes of psychosis. Laboratory tests, biologic markers, and commonly available brain imaging techniques do not assist in the diagnosis of schizophrenia or selection of medication. A pretreatment patient workup not only is important in excluding other pathology but also serves as a baseline for monitoring potential medication-related side effects, and should include vital signs, complete blood count, electrolytes, hepatic function, renal function, electrocardiogram (ECG), fasting serum glucose, serum lipids, thyroid function, and urine drug screen.

Both first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (with the exception of clozapine) are first-line agents in the treatment of schizophrenia.24,28 No absolute criterion distinguishes atypical (second-generation) from typical (traditional or FGA) antipsychotics, and no universally accepted definition exists for an atypical antipsychotic.22 Therefore, second-generation antipsychotic is a more appropriate term. Common to all definitions is the ability of the drug to produce antipsychotic response with few or no acutely occurring extrapyramidal side effects (EPS). Other attributes that have been ascribed to SGAs include enhanced efficacy (particularly for negative symptoms and cognition), absence or near absence of propensity to cause tardive dyskinesia, and lack of effect on serum prolactin.22 To date, the only approved SGA that fulfills all of these criteria is clozapine.22 Although early studies suggested that SGAs might have a superior effect on negative symptoms and cognition, this has not been confirmed in more recent studies.2,24 The major factor in distinguishing among antipsychotics is adverse effects.29 The major advantage of SGAs is their lower risk of neurologic side effects, particularly effects on movement. However, this is offset by increased risk of metabolic side effects with some SGAs, including weight gain, hyperlipidemias, and diabetes mellitus. ![]() Side effect profiles differ among antipsychotics, and this information in combination with individual patient characteristics should be used in deciding which drug to use in an individual patient.

Side effect profiles differ among antipsychotics, and this information in combination with individual patient characteristics should be used in deciding which drug to use in an individual patient.

Results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study indicate that olanzapine, compared with quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and the FGA perphenazine, has modest, but not statistically significant, superiority in maintenance therapy when treatment persistence is the primary clinical outcome.29 However, increased metabolic adverse effects occurred with olanzapine.

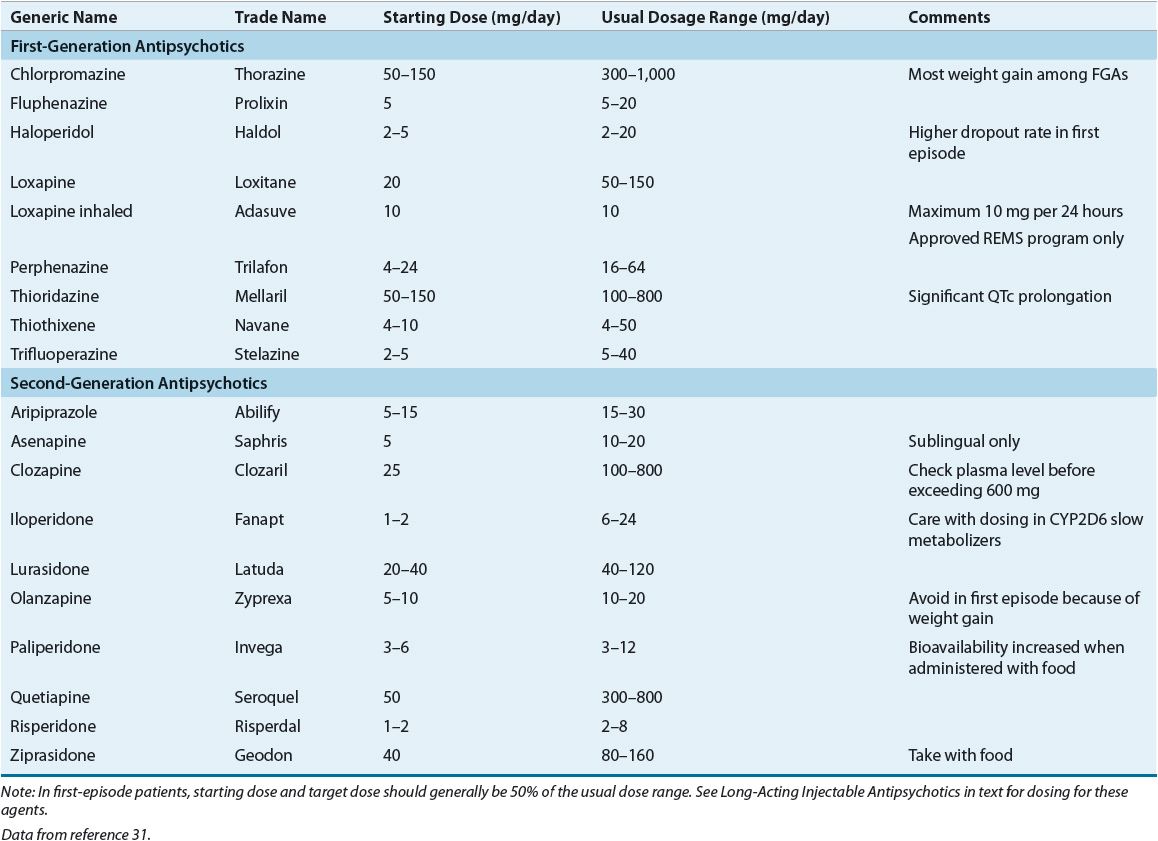

No known differences exist in efficacy between low- and high-potency FGAs. Previous patient or family history of response to an antipsychotic is helpful in the selection of an agent. Table 50-5 lists antipsychotics and their usual dosage ranges.

TABLE 50-5 Available Antipsychotics and Dosage Ranges

Published Guidelines and an Algorithm Example

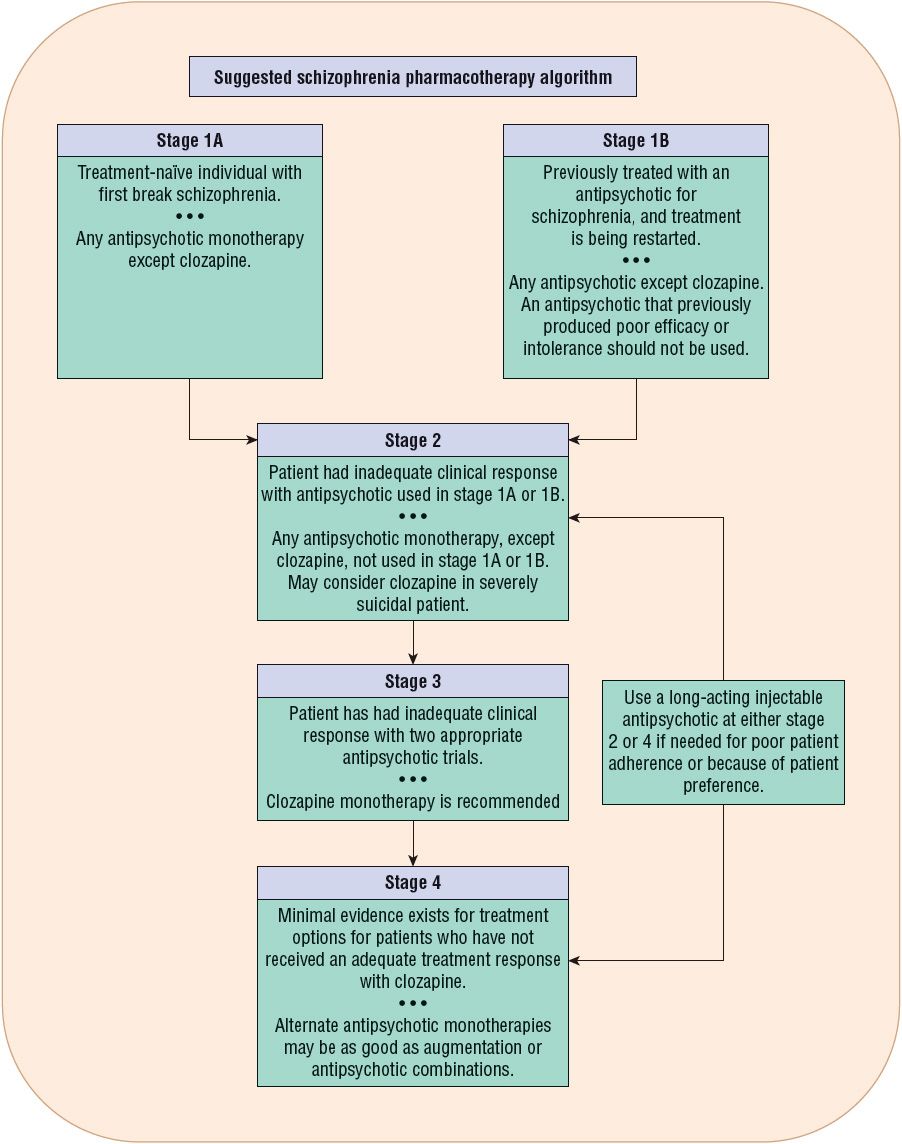

![]() Figure 50-1 outlines a suggested pharmacotherapeutic algorithm for schizophrenia. This algorithm is based on the compilation of three evidence-based guidelines, the 2009 update of the practice guideline from the American Psychiatric Association (APA),30 the 2009 update of the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) guidelines,28 and the 2012 update of the guidelines from the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry.31

Figure 50-1 outlines a suggested pharmacotherapeutic algorithm for schizophrenia. This algorithm is based on the compilation of three evidence-based guidelines, the 2009 update of the practice guideline from the American Psychiatric Association (APA),30 the 2009 update of the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) guidelines,28 and the 2012 update of the guidelines from the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry.31

FIGURE 50-1 Suggested pharmacotherapy algorithm for treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia should be treated in the context of an interprofessional model that addresses the psychosocial needs of the patient, necessary psychiatric pharmacotherapy, psychiatric comorbidities, treatment adherence, and any medical problems the patient may have. See the text for a description of the algorithm stages. (Data from references 28, 30, and 31.)

Stage 1A of the treatment algorithm applies to those patients experiencing their first acute episode of schizophrenia. All available antipsychotics except clozapine are recommended for monotherapy treatment in stage 1A. The clinician needs to evaluate the relative risk of EPS with FGAs versus the risk of metabolic side effects with different SGAs in making a decision for drug selection. The World Federation favors SGAs because of the reduced risk of EPS.31 The 2009 PORT recommendations advise against the use of olanzapine in first episode because of weight gain and metabolic side effects.28,31 Compared with SGAs, haloperidol produced more pseudoparkin-sonism and a higher 1-year discontinuation rate in the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST).30,31 If an FGA is used, it is better to use a moderate-potency antipsychotic such as loxapine or perphenazine. Among the more established SGAs, aripiprazole and ziprasidone produce the least weight gain. Because of the sensitivity to antipsychotic-induced EPS in first-episode patients, antipsychotic dosing should be initiated at the lower end of the dose range.31

Clinical Controversy

Stage 1B addresses those patients who have been previously treated with an antipsychotic, are currently off medications, and are experiencing a recurrent acute psychotic episode. Any antipsychotic monotherapy except clozapine is recommended. However, an antipsychotic that previously produced nonresponse or intolerance should not be used.31

Stage 2 addresses pharmacotherapy in a patient who had inadequate clinical improvement with the antipsychotic used in stage 1A or 1B. Stage 2 recommends an alternate antipsychotic monotherapy with the exception of clozapine.28,31 Because of safety concerns and the need for white blood cell (WBC) monitoring, it is recommended that patients be tried on two different monotherapy antipsychotic trials before proceeding to a trial of clozapine (stage 3).28,31 However, clozapine has superior efficacy in decreasing suicidal behavior, and it should be considered at stage 2 for the suicidal patient.28 Clozapine can also be considered at stage 2 in patients with a history of violence or comorbid substance abuse.28

If partial or poor adherence contributes to inadequate clinical improvement, then long-acting injectable antipsychotics should be considered.24,28,31 In addition to individuals who are identified as partially adherent, some patients may elect long-acting injections instead of taking daily oral medication.

In stage 3, treatment failure on two different antipsychotics from different classes meets the definition of treatment resistance, and the recommended treatment is clozapine.28,30,31

In stage 4, only minimal evidence exists for any treatment options for those patients who do not have adequate symptom improvement with clozapine. Additional treatment options that are tried, again with minimal evidence, include electroconvulsive therapy augmentation, mood stabilizer augmentation, and another antipsychotic combined with clozapine.28,31 The use of antipsychotic combinations is controversial, as limited evidence supports increased efficacy for combination antipsychotic treatment.28,31

Predictors of Response

Obtaining a thorough medication history is important, and previous antipsychotic treatment should help guide the selection of drug therapy, in that either a good prior response favors the use of the same agent or a negative prior response suggests the selection of a dissimilar drug. Nonprescription and illicit drug use can influence psychiatric presentation and thus diagnosis or antipsychotic response. Amphetamines and other CNS stimulants, cocaine, corticosteroids, digitalis glycosides, indomethacin, marijuana, pentazocine, phencyclidine, and other drugs can induce psychosis in susceptible individuals or exacerbate psychosis in patients with preexisting psychiatric illness.32 Patients with schizophrenia who continue to abuse alcohol or drugs usually have a poor response to medications and a poor prognosis. Alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine use potentially results in drug interactions.

Individual differences in patient response have been either proposed or identified, which can be clinically useful predictors of response.23,24 Acute onset and short duration of illness, presence of acute stressors or precipitating factors, later age of onset, family history of affective illness, and good premorbid adjustment as reflected in stable interpersonal relationships or employment are all predictors of good response.23,24

Although controversial, affective symptoms can correlate with an overall good response. Negative symptoms and neuropsychological deficits related to cognition and neurologic soft signs can correlate with poor antipsychotic response.23,24 A patient’s subjective response within the first 48 hours after being administered an FGA can be associated with drug responsiveness.33 An initial dysphoric response, demonstrated by stating a dislike of the medication, or feeling worse or zombie-like, combined with anxiety or akathisia-like symptoms, is associated with poor drug response, adverse effects, and nonadherence.

The importance of developing a therapeutic alliance between the patient and the clinician cannot be underestimated. Patients who form positive therapeutic alliances are more likely to be adherent with all aspects of therapy, experience a better outcome at 2 years, and require smaller antipsychotic doses.

A certain minority of patients fail to benefit from antipsychotic therapy, and their psychosocial functioning can actually worsen. Unfortunately, no accepted method is available to identify these people before treatment.23,24 Recent evidence suggests that pharmacogenetics can play a role in predicting treatment response, both with respect to symptom improvement and with liability to develop side effects.34,35 However, insufficient information is available to recommend routine clinical testing.

Initial Treatment in an Acute Psychotic Episode

The goals during the first 7 days of treatment should be decreased agitation, hostility, combativeness, anxiety, tension, and aggression, and normalization of sleep and eating patterns. The usual recommendation is to initiate therapy and to titrate dose over the first few days to an average effective dose, unless the patient’s physiologic status or history indicates that this dose can result in unacceptable adverse effects. Because of its strong α1-antagonism and resulting risk of hypotension, iloperidone and clozapine should be titrated more slowly than other antipsychotics. Table 50-5 lists the usual dosage range, and an average dose is typically midrange. Because of increased sensitivity to side effects, particularly EPS, in first-episode psychotic patients, typical dosing ranges are approximately 50% of the doses used in chronically ill individuals.28,31 If “cheeking” of medication is suspected, liquid formulations and orally disintegrating tablets of different antipsychotics are available. If a patient has shown absolutely no improvement after 2 to 4 weeks at therapeutic doses, then an alternative antipsychotic should be considered (i.e., moving to the next treatment stage in the algorithm; see Fig. 50-1).22,23

Clinical Controversy

Although some clinicians believe that larger daily doses are necessary in more severely symptomatic patients, data are not available to support this practice. Some symptoms, such as agitation, tension, aggression, and increased motor activity, can respond more quickly, but side effects can be more common with higher doses. However, interindividual differences in dosage and patient response do occur. In partial but inadequate responders who are tolerating the chosen antipsychotic, it may be reasonable to titrate above usual dose ranges. However, this tactic should be time-limited (i.e., 2 to 4 weeks), and if the patient does not achieve further improvement, either the dose should be decreased or an alternative treatment strategy should be tried. In general, rapid titration of antipsychotic dosage is not indicated.23,28 However, intramuscular antipsychotic administration (e.g., aripiprazole 5.25 to 9.75 mg IM, haloperidol 2 to 5 mg IM, olanzapine 2.5 to 10 mg IM, or ziprasidone 10 to 20 mg IM) can be used to assist in calming a severely agitated patient. Agitation can be manifested as loud, physically or verbally threatening behavior, motor hyperactivity, or physical aggression. Although this technique can assist in calming an acutely agitated psychotic patient, it does not improve the extent of remission, or time to remission, or the length of hospitalization. If haloperidol IM is used, the occurrence of EPS can eliminate some of the advantages of using an oral SGA. If the patient is receiving an antipsychotic within the usual therapeutic range, the use of lorazepam 2 mg IM as needed in combination with the maintenance antipsychotic is a rational alternative to an injectable antipsychotic. Hypotension, respiratory depression, CNS depression, and death are possible when injectable lorazepam is used in combination with either olanzapine or clozapine; thus, this parenteral combination is not recommended.30,31

The initial Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for inhaled loxapine powder was approved by the FDA with an indication of treatment of acute agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Because of the risk of bronchospasm, pulmonary distress, and pulmonary arrest, the medication can only be administered in a healthcare facility and through the FDA-approved REMS. Before administration, patients must be screened for a history of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other lung disease associated with bronchospasm, and use is limited to one 10 mg inhaled dose per 24-hour period.36 It is not known whether inhaled loxapine offers any therapeutic advantages in acute agitation compared with currently available IM or oral products. Similarly, the safety of this product when used in routine clinical practice is unclear.

Stabilization Therapy

Improvement is usually a slow but steady process over 6 to 12 weeks or longer. During the first 2 to 3 weeks, goals should include increased socialization and improvement in self-care habits and mood. Improvement in formal thought disorder should follow and can take an additional 6 to 8 weeks to respond. Patients who are early in the course of their illness can experience a more rapid resolution of symptoms than individuals who are more chronically ill. In general, if a patient has no improvement with treatment after 2 to 4 weeks at therapeutic doses, or has achieved only a partial decrease in positive symptoms within 12 weeks at adequate doses, then the next algorithm stage should be considered. In more chronically ill patients, symptoms may continue to improve over 3 to 6 months. During acute stabilization, usual FDA-labeled doses of SGAs are recommended (see Table 50-5).24 An optimum dose of the chosen drug should be estimated in the initial treatment plan. If the patient begins to show adequate response before or at this dosage, then the patient should remain at this dosage as long as symptoms continue to improve. ![]() In general, adequate time on a therapeutic antipsychotic dose is the most important factor in predicting medication response. However, if necessary, dose titration can continue within the therapeutic range every 1 or 2 weeks as long as the patient has no side effects.

In general, adequate time on a therapeutic antipsychotic dose is the most important factor in predicting medication response. However, if necessary, dose titration can continue within the therapeutic range every 1 or 2 weeks as long as the patient has no side effects.

Before changing medications in a poorly responding patient, the following should be considered: Were the initial target symptoms indicative of schizophrenia or did they represent manifestations of a different diagnosis, a long-standing behavioral problem, a substance abuse disorder, or a general medical condition? Is the patient adherent with pharmacotherapy? Are the persistent symptoms poorly responsive to antipsychotics (e.g., impaired insight or judgment, or fixed delusions)? How does the patient’s current status compare with response during previous exacerbations? Would this patient potentially benefit from a change to a different treatment stage (see Fig. 50-1)? Does this patient have a treatment-resistant schizophrenic illness?

The conclusion that a partially responding patient has achieved as much symptomatic improvement as possible is one that must be made with great care. Treatment goals must be realistic. Medications are effective at decreasing many of the symptoms of schizophrenia (and are thus referred to as palliative), but they are not curative, and all symptoms may not abate. Although one should aim to achieve none to minimal residual positive symptoms with effective treatment, it is still unclear what a realistic goal is with regard to maximum improvement in negative symptoms.

It is important to screen patients for co-occurring mental disorders, and their presence can become more apparent during the stabilization or maintenance phases of schizophrenia treatment. Examples include substance abuse disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder. As co-occurring disorders will limit symptom and functional improvement and increase the risk of relapse, it is critical that treatment for the co-occurring disorder be implemented in combination with evidence-based treatment for schizophrenia.

Maintenance Treatment

Maintenance drug therapy prevents relapse, as shown in numerous double-blind studies. The average relapse rate after 1 year is 18% to 32% with active drug (including some nonadherent patients) versus 60% to 80% for placebo.24,37 Avoiding relapses is thus a major goal of treatment.38

After treatment of the first psychotic episode in a patient with schizophrenia, medication should be continued for at least 12 months after remission.24,29,31 ![]() Many schizophrenia experts recommend that patients with robust medication response be treated for at least 5 years. In chronically ill individuals, continuous or lifetime pharmacotherapy is necessary in the majority of patients to prevent relapse. This should be approached with the lowest effective dose of the antipsychotic that is likely to be tolerated by the patient.24,29,31

Many schizophrenia experts recommend that patients with robust medication response be treated for at least 5 years. In chronically ill individuals, continuous or lifetime pharmacotherapy is necessary in the majority of patients to prevent relapse. This should be approached with the lowest effective dose of the antipsychotic that is likely to be tolerated by the patient.24,29,31

Antipsychotics should be tapered slowly before discontinuation. Abrupt discontinuation of antipsychotics, especially clozapine, can result in withdrawal symptoms, felt to be a manifestation of rebound cholinergic outflow. Insomnia, nightmares, headaches, GI symptoms (e.g., abdominal cramps, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), restlessness, increased salivation, and sweating are reported. Although available evidence does not indicate a best way to switch from one antipsychotic to another, it is often recommended to taper and discontinue the first antipsychotic over at least 1 to 2 weeks while the second antipsychotic is initiated and the dose titrated.24,31 Tapering needs to occur more slowly with clozapine.24

Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics

Long-acting antipsychotics are recommended for patients who are unreliable in taking oral medication on a daily basis, and thus are not usually used as first-line therapy. Before a long-acting antipsychotic is initiated, it should be determined whether the patient’s medication nonadherence is because of side effects. If so, an alternative medication with a more favorable side effect profile should be considered before a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. The patient’s motivation for treatment is a major factor influencing outcome. Conversion from oral therapy to a long-acting injectable is most successful in patients who have been stabilized on oral therapy. The ideal patient for a long-acting injectable is the individual who does not like the daily reminder of oral medication or is unreliable in taking medications.

Paliperidone palmitate is a long-acting injectable that has the advantage of once-monthly injections and easy conversion from oral to IM treatment.39 Olanzapine pamoate monohydrate is a long-acting injectable that is administered every 2 or 4 weeks. It is associated with a postinjection sedation/delirium syndrome occurring in approximately 2% of patients.40 The risk of occurrence does not appear related to dose or duration of treatment. One hypothesis is that its occurrence may be associated with accidental entry of the drug into the bloodstream.40 The product labeling contains an FDA black box warning regarding this syndrome. Olanzapine pamoate is subject to a REMS, and the FDA labeling restricts the availability of long-acting olanzapine to a restricted distribution program. The injection must be administered in a registered healthcare facility, and the patient must be observed by a health professional for at least 3 hours after administration.41 A long-acting formulation of aripiprazole is under FDA review at the time of publication, and a once-weekly oral formulation is in development.

Conversion from an oral antipsychotic to a long-acting medication should start with stabilization on an oral dosage form of the same agent, for a short trial (3 to 7 days), to determine whether the patient tolerates the medication without significant side effects. With long-acting risperidone, measurable serum concentrations are not seen until approximately 3 weeks after single-dose administration. Thus, it is important that the oral antipsychotic be administered for at least 3 weeks after beginning the injections. Dose adjustments are recommended to be made no more often than once every 4 weeks.42 The recommended starting dose with risperidone long-acting injection is 25 mg, and clinical experience suggests that titration to doses greater than or equal to 37.5 mg per injection may be necessary for maintenance treatment. Long-acting risperidone has demonstrated efficacy, with an optimum dose range between 25 and 50 mg given IM every 2 weeks. Doses above 50 mg every 2 weeks are not recommended, as research indicates no greater efficacy but more EPS.42

Paliperidone palmitate can be injected into either the deltoid or the gluteal muscle, and treatment is initiated with 234 mg on day 1 and 156 mg a week later. No overlap with oral drug is necessary. Monthly IM doses are then titrated according to response within a range of 39 to 234 mg.39 Olanzapine pamoate monohydrate is recommended for deep gluteal injection, and the initial injectable dose varies from 210 to 405 mg depending on the oral olanzapine daily maintenance dose and the frequency of injectable administration. The official product information should be consulted regarding preparation and administration information.40,41

For fluphenazine decanoate, the simplest dosing conversion method recommends 1.2 times the oral fluphenazine daily dose for stabilized patients, rounding up to the nearest 12.5-mg interval, administered in weekly doses for the first 4 to 6 weeks; or 1.6 times the oral daily dose for more acutely ill patients.43 Subsequently, fluphenazine decanoate can be administered once every 2 to 3 weeks. Oral fluphenazine can be overlapped for 1 week. For haloperidol decanoate, a factor of 10 to 15 times the oral haloperidol daily dose is commonly recommended, rounding up to the nearest 50-mg interval, administered in a once-monthly dose with an oral haloperidol overlap for the first month. A more assertive conversion method recommends 20 times the oral daily dose, but dividing the injection into consecutive doses of 100 to 200 mg every 3 to 7 days until the entire amount is given.44 With this method, oral medication overlap is unnecessary. The haloperidol decanoate dose is decreased by 25% at both second and third months.

Methods to Enhance Patient Adherence

It is often challenging for individuals with chronic illnesses to maintain appropriate medication adherence, and partial compliance is a reality in the treatment of all chronic illnesses.31 Individuals with serious mental disorders have somewhat higher nonadherence rates than those with general medical disorders, with the following explanations provided: denial of illness, lack of insight, grandiosity or paranoia, no perceived need for medication, perceived lack of input into choice of medication or dosage, side effects, misperceived “allergies,” or the number of medications prescribed or doses received daily. It is estimated that half of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder take their medication less than 70% of the time.31 Clinicians should expect partial medication compliance to be the norm. This should be approached in a nonjudgmental manner, with the clinician actively engaging the patient in care and using motivational interviewing techniques as mechanisms to enhance therapeutic alliance and patient adherence.

Numerous different methods have been used in an attempt to improve treatment adherence of patients with schizophrenia. Interventions that provide continuous focus on adherence and that are of long duration have shown benefit. These should incorporate problem solving techniques and be accompanied by technical learning aids. Pharmacy-based interventions and ones using nurse case managers have shown promise in improving adherence.45 It has been suggested that programs need to include a focus on patient-driven outcomes, and not just medication adherence. For example, interventions should include efforts to allow patients to achieve life goals and function. This requires that programs be tailored to the needs of individual patients.45 Psychoeducation strategies should include motivational interview techniques in individual counseling as well as group activities. ![]()

Some studies suggest that compliance therapy, targeted cognitive behavioral therapy focusing on medication adherence, can improve patient adherence, but the success seen in early studies has not been consistently replicated.45

Groups facilitated by trained individuals who have the illness are alleged to be more effective in enhancing awareness and acceptance of schizophrenia and necessary treatment than groups led only by professionals. Active involvement of family members further increases the likelihood of patient adherence with treatment. In addition to programs provided by community mental health centers, support groups operated by consumer groups such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) are available in most urban areas. In the hospital, self-medication administration can reinforce the patient’s perception of his or her active role in his or her own treatment. When patients miss outpatient appointments, active outreach interventions must be implemented to enhance patient engagement in treatment.24,45

Management of Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia

In general, “treatment resistant” describes a patient who has had inadequate symptom response from multiple antipsychotic trials.24 Traditionally, treatment resistance has been defined as lack of improvement in positive symptoms, but it can be defined by poor improvement in negative symptoms, or even by medication intolerance. Between 10% and 30% of patients receive minimal symptomatic improvement after multiple FGA monotherapy trials.24 An additional 30% to 60% of patients have partial but inadequate improvement in symptoms or unacceptable side effects associated with antipsychotic use.24,31 In those patients failing two or more pharmacotherapy trials, a treatment-refractory evaluation should be performed to reexamine diagnosis, substance abuse, medication adherence, and psychosocial stressors. Targeted cognitive behavioral therapy or other psychosocial augmentation strategies should be considered.31

Clozapine

Only clozapine has shown superiority over other antipsychotics in randomized clinical trials for the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Most other SGAs have either not been studied in treatment-refractory patients or been evaluated in small open trials. In a seminal study, clozapine was effective in approximately 30% of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, compared with only 4% treated with a combination of chlorpromazine and benztropine.46 The criteria for treatment resistance require two treatment failures, and include both FGAs and SGAs. Other treatment candidates for clozapine include those patients who cannot tolerate neurologic side effects of even conservative doses of other antipsychotics.