Special Considerations

For the patient with a disorder involving the fovea centralis (or the area surrounding it), teach him to periodically use the Amsler grid to detect progression of macular degeneration.

Patient Counseling

Explain the progression and complications of the disease, and discuss which assistive devices and rehabilitation services the patient may need. Stress the importance of regular eye examinations, and emphasize which signs and symptoms the patient should report. If the disorder involves the fovea centralis, explain the use of the Amsler grid.

Pediatric Pointers

In young children, visual field testing is difficult and requires patience. Confrontation visual field testing is the method of choice.

REFERENCES

Biswas, J., Krishnakumar, S., & Ahuja, S. (2010). Manual of ocular pathology. New Delhi, India: Jaypee–Highlights Medical Publishers.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Levin, L. A., & Albert, D. M. (2010). Ocular disease: Mechanisms and management. London, UK: Saunders, Elsevier.

Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee–Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

Scrotal Swelling

Scrotal swelling occurs when a condition affecting the testicles, epididymis, or scrotal skin produces edema or a mass; the penis may be involved. Scrotal swelling can affect males of any age. It can be unilateral or bilateral and painful or painless.

The sudden onset of painful scrotal swelling suggests torsion of a testicle or testicular appendages, especially in a prepubescent male. This emergency requires immediate surgery to untwist and stabilize the spermatic cord or to remove the appendage.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If severe pain accompanies scrotal swelling, ask the patient when the swelling began. Using a Doppler stethoscope, evaluate blood flow to the testicle. If it’s decreased or absent, suspect testicular torsion and prepare the patient for surgery. Withhold food and fluids, insert an I.V. line, and apply an ice pack to the scrotum to reduce pain and swelling. An attempt may be made to untwist the cord manually, but even if this is successful, the patient may still require surgery for stabilization.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, proceed with the history. Ask about injury to the scrotum, urethral discharge, cloudy urine, increased urinary frequency, and dysuria. Is the patient sexually active? When was his last sexual contact? Does he have a history of sexually transmitted disease? Find out about recent illnesses, particularly mumps. Does he have a history of prostate surgery or prolonged catheterization? Does changing his body position or level of activity affect the swelling?

Take the patient’s vital signs, especially noting a fever, and palpate his abdomen for tenderness. Then, examine the entire genital area. Assess the scrotum with the patient supine and standing. Note its size and color. Is the swelling unilateral or bilateral? Do you see signs of trauma or bruising? Are there rashes or lesions present? Gently palpate the scrotum for a cyst or lump. Note especially tenderness or increased firmness. Check the testicles’ position in the scrotum. Finally, transilluminate the scrotum to distinguish a fluid-filled cyst from a solid mass. (A solid mass can’t be transilluminated.)

Medical Causes

- Epididymal cysts. Located in the head of the epididymis, epididymal cysts produce painless scrotal swelling.

- Epididymitis. Key features of inflammation are pain, extreme tenderness, and swelling in the groin and scrotum. The patient waddles to avoid pressure on the groin and scrotum during walking. He may have a high fever, malaise, a urethral discharge and cloudy urine, and lower abdominal pain on the affected side. His scrotal skin may be hot, red, dry, flaky, and thin.

- Hydrocele. Fluid accumulation produces gradual scrotal swelling that’s usually painless. The scrotum may be soft and cystic or firm and tense. Palpation reveals a round, nontender scrotal mass.

- Idiopathic scrotal edema. Swelling occurs quickly with idiopathic scrotal edema and usually disappears within 24 hours. The affected testicle is pink.

- Orchitis (acute). Mumps, syphilis, or tuberculosis may precipitate orchitis, which causes sudden painful swelling of one or, at times, both testicles. Related findings include a hot, reddened scrotum; a fever of up to 104°F (40°C); chills; lower abdominal pain; nausea; vomiting; and extreme weakness. Urinary signs are usually absent.

- Scrotal trauma. Blunt trauma causes scrotal swelling with bruising and severe pain. The scrotum may appear dark or bluish.

- Spermatocele. Spermatocele is a usually painless cystic mass that lies above and behind the testicle and contains opaque fluid and sperm. Its onset may be acute or gradual. Less than 1 cm in diameter, it’s movable and may be transilluminated.

- Testicular torsion. Most common before puberty, testicular torsion is a urologic emergency that causes scrotal swelling; sudden, severe pain; and, possibly, elevation of the affected testicle within the scrotum. It may also cause nausea and vomiting.

- Testicular tumor. Typically painless, smooth, and firm, a testicular tumor produces swelling and a sensation of excessive weight in the scrotum.

- Torsion of a hydatid of Morgagni. Torsion of this small, pea-sized cyst severs its blood supply, causing a hard, painful swelling on the testicle’s upper pole.

Other Causes

- Surgery. An effusion of blood from surgery can produce a hematocele, leading to scrotal swelling.

Special Considerations

Keep the patient on bed rest and administer an antibiotic. Provide adequate fluids, fiber, and stool softeners. Place a rolled towel between the patient’s legs and under the scrotum to help reduce severe swelling. Or, if the patient has mild or moderate swelling, advise him to wear a loose-fitting athletic supporter lined with a soft cotton dressing. For several days, administer an analgesic to relieve his pain. Encourage sitz baths, and apply heat or ice packs to decrease inflammation.

Prepare the patient for needle aspiration of fluid-filled cysts and other diagnostic tests, such as lung tomography and a computed tomography scan of the abdomen, to rule out malignant tumors.

Patient Counseling

Explain to the patient the importance of performing testicular self-examinations, and instruct the patient on the proper technique, if needed.

Pediatric Pointers

A thorough physical assessment is especially important for children with scrotal swelling, who may be unable to provide history data. In children up to age 1, a hernia or hydrocele of the spermatic cord may stem from abnormal fetal development. In infants, scrotal swelling may stem from ammonia-related dermatitis, if diapers aren’t changed often enough. In prepubescent males, it usually results from torsion of the spermatic cord.

Other disorders that can produce scrotal swelling in children include epididymitis (rare before age 10), traumatic orchitis from contact sports, and mumps, which usually occurs after puberty.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Seizures, Absence

Absence seizures are benign, generalized seizures thought to originate subcortically. These brief episodes of unconsciousness usually last 3 to 20 seconds and can occur 100 or more times per day, causing periods of inattention. Absence seizures usually begin between ages 4 and 12. Their first sign may be deteriorating school work and behavior. The cause of these seizures is unknown.

Absence seizures occur without warning. The patient suddenly stops all purposeful activity and stares blankly ahead, as if he were daydreaming. Absence seizures may produce automatisms, such as repetitive lip smacking, or mild clonic or myoclonic movements, including mild jerking of the eyelids. The patient may drop an object that he’s holding, and muscle relaxation may cause him to drop his head or arms or to slump. After the attack, the patient resumes activity, typically unaware of the episode.

Absence status, a rare form of absence seizure, occurs as a prolonged absence seizure or as repeated episodes of these seizures. Usually not life-threatening, it occurs most commonly in patients who have previously experienced absence seizures.

History and Physical Examination

If you suspect a patient is having an absence seizure, evaluate its occurrence and duration by reciting a series of numbers and then asking him to repeat them after the attack ends. If the patient has had an absence seizure, he can’t do this. Alternatively, if the seizures are occurring within minutes of each other, ask the patient to count for about 5 minutes. He’ll stop counting during a seizure and resume when it’s over. Look for accompanying automatisms. Find out if the family has noticed a change in behavior or deteriorating schoolwork.

Medical Causes

- Idiopathic epilepsy. Some forms of absence seizure are accompanied by learning disabilities.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, and EEGs. Administer an anticonvulsant, as ordered. Provide emotional support to the patient and his family. Ensure a safe environment for the patient.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms require immediate attention, and emphasize the importance of follow-up care. Include the patient’s teacher and school nurse in the teaching process, if possible. Discuss the need to wear medical identification.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Seizures, Complex Partial

A complex partial seizure occurs when a focal seizure begins in the temporal lobe and causes a partial alteration of consciousness — usually confusion. Psychomotor seizures can occur at any age, but their incidence usually increases during adolescence and adulthood. Two-thirds of patients also have generalized seizures.

An aura — usually a complex hallucination, illusion, or sen- sation — typically precedes a psychomotor seizure. The hallucination may be audiovisual (images with sounds), auditory (abnormal or normal sounds or voices from the patient’s past), or olfactory (unpleasant smells, such as rotten eggs or burning materials). Other types of auras include sensations of déjà vu, unfamiliarity with surroundings, or depersonalization. The patient may become fearful or anxious, experience lip smacking, or have an unpleasant feeling in the epigastric region that rises toward the chest and throat. The patient usually recognizes the aura and lies down before losing consciousness.

A period of unresponsiveness follows the aura. The patient may experience automatisms, appear dazed and wander aimlessly, perform inappropriate acts (such as undressing in public), be unresponsive, utter incoherent phrases, or (rarely) go into a rage or tantrum. After the seizure, the patient is confused and drowsy and doesn’t remember the seizure. Behavioral automatisms rarely last longer than 5 minutes, but postseizure confusion, agitation, and amnesia may persist.

Between attacks, the patient may exhibit slow and rigid thinking, outbursts of anger and aggressiveness, tedious conversation, a preoccupation with naive philosophical ideas, a diminished libido, mood swings, and paranoid tendencies.

History

If you witness a complex partial seizure, never attempt to restrain the patient. Instead, lead him gently to a safe area. (Exception: Don’t approach him if he’s angry or violent.) Calmly encourage him to sit down, and remain with him until he’s fully alert. After the seizure, ask him if he experienced an aura. Record all observations and findings.

Medical Causes

- Brain abscess. If the brain abscess is in the temporal lobe, complex partial seizures commonly occur after the abscess disappears. Related problems may include a headache, nausea, vomiting, generalized seizures, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC). The patient may also develop central facial weakness, auditory receptive aphasia, hemiparesis, and ocular disturbances.

- Head trauma. Severe trauma to the temporal lobe (especially from a penetrating injury) can produce complex partial seizures months or years later. The seizures may decrease in frequency and eventually stop. Head trauma also causes generalized seizures and behavior and personality changes.

- Herpes simplex encephalitis. The herpes simplex virus commonly attacks the temporal lobe, resulting in complex partial seizures. Other features include a fever, a headache, coma, and generalized seizures.

- Temporal lobe tumor. Complex partial seizures may be the first sign of a temporal lobe tumor. Other signs and symptoms include a headache, pupillary changes, and mental dullness. Increased intracranial pressure may cause a decreased LOC, vomiting, and, possibly, papilledema.

Special Considerations

After the seizure, remain with the patient to reorient him to his surroundings and to protect him from injury. Keep him in bed until he’s fully alert, and remove harmful objects from the area. Offer emotional support to the patient and his family, and teach them how to cope with seizures.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as EEG, computed tomography scans, or magnetic resonance imaging.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient and his family in safety measures to take during a seizure, and explain the importance of carrying medical identification. Discuss methods for coping with seizures, and emphasize compliance with drug therapy.

Pediatric Pointers

Complex partial seizures in children may resemble absence seizures. They can result from birth injury, abuse, infection, or cancer. In about one-third of patients, their cause is unknown.

Repeated complex partial seizures commonly lead to generalized seizures. The child may experience a slight aura, which is rarely as clearly defined as that seen with generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Seizures, Generalized Tonic-Clonic

Like other types of seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures are caused by the paroxysmal, uncontrolled discharge of central nervous system neurons, leading to neurologic dysfunction. Unlike most other types of seizures, however, this cerebral hyperactivity isn’t confined to the original focus or to a localized area but extends to the entire brain.

A generalized tonic-clonic seizure may begin with or without an aura. As seizure activity spreads to the subcortical structures, the patient loses consciousness, falls, and may utter a loud cry that’s precipitated by air rushing from the lungs through the vocal cords. His body stiffens (tonic phase), and then undergoes rapid, synchronous muscle jerking and hyperventilation (clonic phase). Tongue biting, incontinence, diaphoresis, profuse salivation, and signs of respiratory distress may also occur. The seizure usually stops after 2 to 5 minutes. The patient then regains consciousness but displays confusion. He may complain of a headache, fatigue, muscle soreness, and arm and leg weakness.

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures usually occur singly. The patient may be asleep or awake and active. (See What Happens During a Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizure.) Possible complications include respiratory arrest due to airway obstruction from secretions, status epilepticus (occurring in 5% to 8% of patients), head or spinal injuries and bruises, Todd’s paralysis, and, rarely, cardiac arrest. Life-threatening status epilepticus is marked by prolonged seizure activity or by rapidly recurring seizures with no intervening periods of recovery. It’s most commonly triggered by the abrupt discontinuation of anticonvulsant therapy.

Generalized seizures may be caused by a brain tumor, vascular disorder, head trauma, infection, metabolic defect, drug or alcohol withdrawal syndrome, exposure to toxins, or a genetic defect. Generalized seizures may also result from a focal seizure. With recurring seizures, or epilepsy, the cause may be unknown.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you witness the beginning of the seizure, first check the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, and ensure that the cause isn’t asystole or a blocked airway. Stay with the patient and ensure a patent airway. Focus your care on observing the seizure and protecting the patient. Place a towel under his head to prevent injury, loosen his clothing, and move any sharp or hard objects out of his way. Never try to restrain the patient or force a hard object into his mouth; you might chip his teeth or fracture his jaw. Only at the start of the ictal phase can you safely insert a soft object into his mouth.

If possible, turn the patient to one side during the seizure to allow secretions to drain and to prevent aspiration. Otherwise, do this at the end of the clonic phase when respirations return. (If they fail to return, check for airway obstruction and suction the patient if necessary. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, and mechanical ventilation may be needed.)

Protect the patient after the seizure by providing a safe area in which he can rest. As he awakens, reassure and reorient him. Check his vital signs and neurologic status. Make sure to carefully record these data and your observations during the seizure.

If the seizure lasts longer than 4 minutes or if a second seizure occurs before full recovery from the first, suspect status epilepticus. Establish an airway, start an I.V. line, give supplemental oxygen, and begin cardiac monitoring. Draw blood for appropriate studies. Turn the patient on his side, with his head in a semi-dependent position, to drain secretions and prevent aspiration. Periodically turn him to the opposite side, check his arterial blood gas levels for hypoxemia, and administer oxygen by mask, increasing the flow rate if necessary. Administer diazepam or lorazepam by slow I.V. push, repeated two or three times at 10- to 20-minute intervals, to stop the seizures. If the patient isn’t known to have epilepsy, an I.V. bolus of dextrose 50% (50 mL) with thiamine (100 mg) may be ordered. Dextrose may stop the seizures if the patient has hypoglycemia. If his thiamine level is low, also give thiamine to guard against further damage.

If the patient is intubated, expect to insert a nasogastric (NG) tube to prevent vomiting and aspiration. Be aware that if the patient hasn’t been intubated, the NG tube itself can trigger the gag reflex and cause vomiting. Make sure to record your observations and the intervals between seizures.

What Happens During a Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizure

BEFORE THE SEIZURE

Prodromal signs and symptoms, such as myoclonic jerks, a throbbing headache, and mood changes, may occur over several hours or days. The patient may have premonitions of the seizure. For example, he may report an aura, such as seeing a flashing light or smelling a characteristic odor.

DURING THE SEIZURE

If a generalized seizure begins with an aura, this indicates that irritability in a specific area of the brain quickly became widespread. Common auras include palpitations, epigastric distress rapidly rising to the throat, head or eye turning, and sensory hallucinations.

Next, loss of consciousness occurs as a sudden discharge of intense electrical activity overwhelms the brain’s subcortical center. The patient falls and experiences brief, bilateral myoclonic contractures. Air forced through spasmodic vocal cords may produce a birdlike, piercing cry.

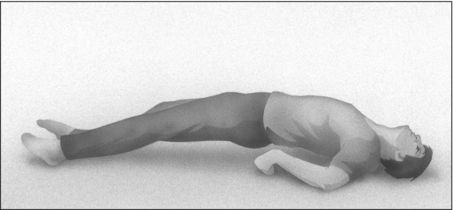

During the tonic phase, skeletal muscles contract for 10 to 20 seconds. The patient’s eyelids are drawn up, his arms are flexed, and his legs are extended. His mouth opens wide, then snaps shut; he may bite his tongue. His respirations cease because of respiratory muscle spasm, and initial pallor of the skin and mucous membranes (the result of impaired venous return) changes to cyanosis secondary to apnea. The patient arches his back and slowly lowers his arms (as shown below). Other effects include dilated, nonreactive pupils, greatly increased heart rate and blood pressure, increased salivation and tracheobronchial secretions, and profuse diaphoresis.

During the clonic phase, lasting about 60 seconds, mild trembling progresses to violent contractures or jerks. Other motor activity includes facial grimaces (with possible tongue biting) and violent expiration of bloody, foamy saliva from clonic contractures of thoracic cage muscles. Clonic jerks slowly decrease in intensity and frequency. The patient is still apneic.

AFTER THE SEIZURE

The patient’s movements gradually cease, and he becomes unresponsive to external stimuli. Other postseizure features include stertorous respirations from increased tracheobronchial secretions, equal or unequal pupils (but becoming reactive), and urinary incontinence due to brief muscle relaxation. After about 5 minutes, the patient’s level of consciousness increases, and he appears confused and disoriented. His muscle tone, heart rate, and blood pressure return to normal.

After several hours’ sleep, the patient awakens exhausted and may have a headache, sore muscles, and amnesia about the seizure.

History and Physical Examination

If you didn’t witness the seizure, obtain a description from the patient’s companion. Ask when the seizure started and how long it lasted. Did the patient report unusual sensations before the seizure began? Did the seizure start in one area of the body and spread, or did it affect the entire body right away? Did the patient fall on a hard surface? Did his eyes or head turn? Did he turn blue? Did he lose bladder control? Did he have other seizures before recovering?

If the patient may have sustained a head injury, observe him closely for loss of consciousness, unequal or nonreactive pupils, and focal neurologic signs. Does he complain of a headache and muscle soreness? Is he increasingly difficult to arouse when you check on him at 20-minute intervals? Examine his arms, legs, and face (including tongue) for injury, residual paralysis, or limb weakness.

Next, obtain a history. Has the patient ever had generalized or focal seizures before? If so, do they occur frequently? Do other family members also have them? Is the patient receiving drug therapy? Is he compliant? Also, ask about sleep deprivation and emotional or physical stress at the time the seizure occurred.

Medical Causes

- Brain abscess. Generalized seizures may occur in the acute stage of abscess formation or after the abscess disappears. Depending on the size and location of the abscess, a decreased level of consciousness (LOC) varies from drowsiness to deep stupor. Early signs and symptoms reflect increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and include a constant headache, nausea, vomiting, and focal seizures. Typical later features include ocular disturbances, such as nystagmus, impaired vision, and unequal pupils. Other findings vary with the abscess site but may include aphasia, hemiparesis, abnormal behavior, and personality changes.

- Brain tumor. Generalized seizures may occur, depending on the tumor’s location and type. Other findings include a slowly decreasing LOC, a morning headache, dizziness, confusion, focal seizures, vision loss, motor and sensory disturbances, aphasia, and ataxia. Later findings include papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and, eventually, a decorticate posture.

- Chronic renal failure. End-stage renal failure produces the rapid onset of twitching, trembling, myoclonic jerks, and generalized seizures. Related signs and symptoms include anuria or oliguria, fatigue, malaise, irritability, decreased mental acuity, muscle cramps, peripheral neuropathies, anorexia, and constipation or diarrhea. Integumentary effects include skin color changes (yellow, brown, or bronze), pruritus, and uremic frost. Other effects include an ammonia breath odor, nausea and vomiting, ecchymoses, petechiae, GI bleeding, mouth and gum ulcers, hypertension, and Kussmaul’s respirations.

- Eclampsia. Generalized seizures are a hallmark of eclampsia. Related findings include a severe frontal headache, nausea and vomiting, vision disturbances, increased blood pressure, a fever of up to 104°F (40°C), peripheral edema, and sudden weight gain. The patient may also exhibit oliguria, irritability, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), and a decreased LOC.

- Encephalitis. Seizures are an early sign of encephalitis, indicating a poor prognosis; they may also occur after recovery as a result of residual damage. Other findings include a fever, a headache, photophobia, nuchal rigidity, neck pain, vomiting, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, nystagmus, irritability, cranial nerve palsies (causing facial weakness, ptosis, dysphagia), and myoclonic jerks.

- Epilepsy (idiopathic). In most cases, the cause of recurrent seizures is unknown.

- Head trauma. In severe cases, generalized seizures may occur at the time of injury. (Months later, focal seizures may occur.) Severe head trauma may also cause a decreased LOC, leading to coma; soft tissue injury of the face, head, or neck; clear or bloody drainage from the mouth, nose, or ears; facial edema; bony deformity of the face, head, or neck; Battle’s sign; and a lack of response to oculocephalic and oculovestibular stimulation. Motor and sensory deficits may occur along with altered respirations. Examination may reveal signs of increasing ICP, such as a decreased response to painful stimuli, nonreactive pupils, bradycardia, increased systolic pressure, and widening pulse pressure. If the patient is conscious, he may exhibit visual deficits, behavioral changes, and a headache.

- Hepatic encephalopathy. Generalized seizures may occur late in hepatic encephalopathy. Associated late-stage findings in the comatose patient include fetor hepaticus, asterixis, hyperactive DTRs, and a positive Babinski’s sign.

- Hypoglycemia. Generalized seizures usually occur with severe hypoglycemia, accompanied by blurred or double vision, motor weakness, hemiplegia, trembling, excessive diaphoresis, tachycardia, myoclonic twitching, and a decreased LOC.

- Hyponatremia. Seizures develop when serum sodium levels fall below 125 mEq/L, especially if the decrease is rapid. Hyponatremia also causes orthostatic hypotension, a headache, muscle twitching and weakness, fatigue, oliguria or anuria, cold and clammy skin, decreased skin turgor, irritability, lethargy, confusion, and stupor or coma. Excessive thirst, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps may also occur. Severe hyponatremia may cause cyanosis and vasomotor collapse, with a thready pulse.

- Hypoparathyroidism. Worsening tetany causes generalized seizures. Chronic hypoparathyroidism produces neuromuscular irritability and hyperactive DTRs.

- Hypoxic encephalopathy. Besides generalized seizures, hypoxic encephalopathy may produce myoclonic jerks and coma. Later, if the patient has recovered, dementia, visual agnosia, choreoathetosis, and ataxia may occur.

- Neurofibromatosis. Multiple brain lesions from neurofibromatosis cause focal and generalized seizures. Inspection reveals café-au-lait spots, multiple skin tumors, scoliosis, and kyphoscoliosis. Related findings include dizziness, ataxia, monocular blindness, and nystagmus.

- Stroke. Seizures (focal more commonly than generalized) may occur within 6 months of an ischemic stroke. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the location and extent of brain damage. They include a decreased LOC, contralateral hemiplegia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, and aphasia. The patient may also develop visual deficits, memory loss, poor judgment, personality changes, emotional lability, urine retention or urinary incontinence, constipation, a headache, and vomiting.

Other Causes

- Arsenic poisoning. Besides generalized seizures, arsenic poisoning may cause a garlicky breath odor, increased salivation, and generalized pruritus. GI effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain. Related effects include diffuse hyperpigmentation; sharply defined edema of the eyelids, face, and ankles; paresthesia of the extremities; alopecia; irritated mucous membranes; weakness; muscle aches; and peripheral neuropathy.

- Barbiturate withdrawal. In chronically intoxicated patients, barbiturate withdrawal may produce generalized seizures 2 to 4 days after the last dose. Status epilepticus is possible.

- Diagnostic tests. Contrast agents used in radiologic tests may cause generalized seizures.

- Drugs. Toxic blood levels of some drugs, such as theophylline, lidocaine, meperidine, penicillins, and cimetidine, may cause generalized seizures. Phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, amphetamines, isoniazid, and vincristine may cause seizures in patients with preexisting epilepsy.

Special Considerations

Closely monitor the patient after the seizure for recurring seizure activity. Prepare him for a computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging and EEG.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient’s family how to observe and record seizure activity, and explain the reasons for doing so. Emphasize the importance of compliance with drug therapy and follow-up, and explain possible adverse reactions to prescribed medications. Advise the patient to carry medical identification at all times.

Pediatric Pointers

Generalized seizures are common in children. In fact, between 75% and 90% of epileptic patients experience their first seizure before age 20. Many children between ages 3 months and 3 years experience generalized seizures associated with a fever; some of these children later develop seizures without a fever. Generalized seizures may also stem from inborn errors of metabolism, perinatal injury, brain infection, Reye’s syndrome, Sturge-Weber syndrome, arteriovenous malformation, lead poisoning, hypoglycemia, and idiopathic causes. The pertussis component of the DPT vaccine may cause seizures; however, this is rare.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Seizures, Simple Partial

Resulting from an irritable focus in the cerebral cortex, simple partial seizures typically last about 30 seconds and don’t alter the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). The type and pattern reflect the location of the irritable focus. Simple partial seizures may be classified as motor (including jacksonian seizures and epilepsia partialis continua) or somatosensory (including visual, olfactory, and auditory seizures).

A focal motor seizure is a series of unilateral clonic (muscle jerking) and tonic (muscle stiffening) movements of one part of the body. The patient’s head and eyes characteristically turn away from the hemispheric focus — usually the frontal lobe near the motor strip. A tonic-clonic contraction of the trunk or extremities may follow.

A Jacksonian motor seizure typically begins with a tonic contraction of a finger, the corner of the mouth, or one foot. Clonic movements follow, spreading to other muscles on the same side of the body, moving up the arm or leg, and eventually involving the whole side. Alternatively, clonic movements may spread to the opposite side, becoming generalized and leading to loss of consciousness. In the postictal phase, the patient may experience paralysis (Todd’s paralysis) in the affected limbs, usually resolving within 24 hours.

Epilepsia partialis continua causes clonic twitching of one muscle group, usually in the face, arm, or leg. Twitching occurs every few seconds and persists for hours, days, or months without spreading. Spasms usually affect the distal arm and leg muscles more than the proximal ones; in the face, they affect the corner of the mouth, one or both eyelids, and, occasionally, the neck or trunk muscles unilaterally.

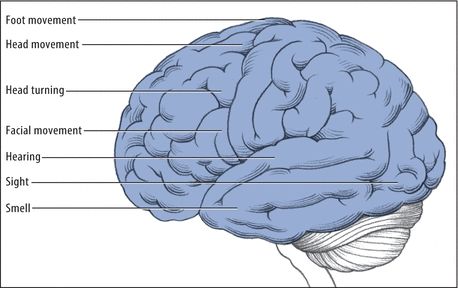

Body Functions Affected by Focal Seizures

The site of the irritable focus determines which body functions are affected by a focal seizure, as shown in the illustration below.

A focal somatosensory seizure affects a localized body area on one side. Usually, this type of seizure initially causes numbness, tingling, or crawling or “electric” sensations; occasionally, it causes pain or burning sensations in the lips, fingers, or toes. A visual seizure involves sensations of darkness or of stationary or moving lights or spots, usually red at first, then blue, green, and yellow. It can affect both visual fields or the visual field on the side opposite the lesion. The irritable focus is in the occipital lobe. In contrast, the irritable focus in an auditory or olfactory seizure is in the temporal lobe. (See Body Functions Affected by Focal Seizures.)

History and Physical Examination

Make sure to record the patient’s seizure activity in detail; your data may be critical in locating the lesion in the brain. Does the patient turn his head and eyes? If so, to what side? Where does movement first start? Does it spread? Because a partial seizure may become generalized, you’ll need to watch closely for loss of consciousness, bilateral tonicity and clonicity, cyanosis, tongue biting, and urinary incontinence. (See Seizures, Generalized Tonic-Clonic, pages 652 to 657.)

After the seizure, ask the patient to describe exactly what he remembers, if anything, about the seizure. Check the patient’s LOC, and test for residual deficits (such as weakness in the involved extremity) and sensory disturbances.

Then, obtain a history. Ask the patient what happened before the seizure. Can he describe an aura or did he recognize its onset? If so, how — by a smell, a visual disturbance, or a sound or visceral phenomenon such as an unusual sensation in his stomach? How does this seizure compare with others he has had?

Also, explore fully any history — recent or remote — of head trauma. Check for a history of stroke or recent infection, especially with a fever, headache, or stiff neck.

Medical Causes

- Brain abscess. Seizures can occur in the acute stage of abscess formation or after resolution of the abscess. A decreased LOC varies from drowsiness to deep stupor. Early signs and symptoms reflect increased intracranial pressure and include a constant, intractable headache; nausea; and vomiting. Later signs and symptoms include ocular disturbances, such as nystagmus, decreased visual acuity, and unequal pupils. Other findings vary according to the abscess site and may include aphasia, hemiparesis, and personality changes.

- Brain tumor. Focal seizures are commonly the earliest indicators of a brain tumor. The patient may report a morning headache, dizziness, confusion, vision loss, and motor and sensory disturbances. He may also develop aphasia, generalized seizures, ataxia, a decreased LOC, papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, and widening pulse pressure. Eventually, he may assume a decorticate posture.

- Head trauma. Any head injury can cause seizures, but penetrating wounds are characteristically associated with focal seizures. The seizures usually begin 3 to 15 months after injury, decrease in frequency after several years, and eventually stop. The patient may develop generalized seizures and a decreased LOC that may progress to coma.

- Stroke. A major cause of seizures in patients older than age 50, a stroke may induce focal seizures up to 6 months after its onset. Related effects depend on the type and extent of the stroke, but may include a decreased LOC, contralateral hemiplegia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, and aphasia. A stroke may also cause visual deficits, memory loss, poor judgment, personality changes, emotional lability, a headache, urinary incontinence or retention, and vomiting. It may result in generalized seizures.

Special Considerations

No emergency care is necessary during a focal seizure, unless it progresses to a generalized seizure. (See Seizures, Generalized Tonic-Clonic, pages 652 to 657.) However, to ensure patient safety, you should remain with the patient during the seizure and reassure him.

Prepare the patient for such diagnostic tests as a computed tomography scan and EEG.

Patient Counseling

Teach the family how to record seizures and the importance of maintaining a safe environment. Emphasize the importance of complying with the prescribed medication regimen. Advise the patient to carry medical identification at all times.

Pediatric Pointers

Affecting more children than adults, focal seizures are likely to spread and become generalized. They typically cause the eyes, or the head and eyes, to turn to the side; in neonates, they cause mouth twitching, staring, or both.

Focal seizures in children can result from hemiplegic cerebral palsy, head trauma, child abuse, arteriovenous malformation, or Sturge-Weber syndrome. About 25% of febrile seizures present as focal seizures.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Setting Sun Sign[Sunset eyes]

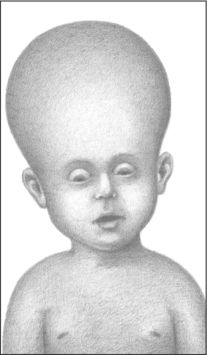

Setting sun sign refers to the downward deviation of an infant’s or a young child’s eyes as a result of pressure on cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. With this late and ominous sign of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), both eyes are rotated downward, typically revealing an area of sclera above the irises; occasionally, the irises appear to be forced outward. Pupils are sluggish, responding to light unequally. (See Identifying Setting Sun Sign.)

The infant with increased ICP is typically irritable and lethargic and feeds poorly. Changes in the level of consciousness (LOC), lower extremity spasticity, and opisthotonos may also be obvious. Increased ICP typically results from space-occupying lesions — such as tumors — or from an accumulation of fluid in the brain’s ventricular system, as occurs with hydrocephalus. It also results from intracranial bleeding or cerebral edema. Other signs include a globular appearance of the head (light bulb sign), a loss of upgaze, and distended scalp veins.

Setting sun sign may be intermittent — for example, it may disappear when the infant is upright because this position slightly reduces ICP. The sign may be elicited in a healthy infant younger than age 4 weeks by suddenly changing his head position, and in a healthy infant up to age 9 months by shining a bright light into his eyes and removing it quickly.

Identifying Setting Sun Sign

With this late sign of increased intracranial pressure in an infant or a young child, pressure on cranial nerves III, IV, and VI forces the eyes downward, revealing a rim of sclera above the irises.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree