Right Hepatectomy

Neil H. Bhayani

Niraj J. Gusani

Kevin Staveley-O’Carroll

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Medical evaluation and suitability for major abdominal surgery is tantamount.

Health of the liver can be ascertained by questions regarding episodes of jaundice, hepatitis exposure, alcohol, illicit drug abuse, and treatment with chemotherapy.

In addition to standard preoperative laboratories, it is our practice to obtain a complete viral hepatitis panel on all potential surgical candidates. Regardless of the metric or risk scoring system employed, thorough assessment of the health of the remnant liver is mandatory.

Previous history of abdominal surgery, especially abdominal foreign bodies (e.g., mesh), may alter the approach.

Physical exam findings of chronic liver disease or hepatic insufficiency should prompt more invasive testing if the patient remains a surgical candidate.

If performing a metastasectomy, there should be a thorough evaluation for extrahepatic disease. Computed tomography (CT) is considered standard of care; a positron emission tomography (PET) scan is currently considered optional but used commonly by the authors. Findings of extrahepatic disease should prompt reconsideration of hepatectomy or planning for multiple staged procedures.

In appropriate, medically operable patients, resectability is now only limited by the need to preserve adequate functional hepatic reserve.

Liver function can be assessed by the Child-Pugh classification or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD). Neither metric has been definitively shown to be superior.2,3

Specific biochemical testing of liver function is more prevalent in Asia but rarely performed in the United States.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Noncontrast, arterial, and venous contrast cross-sectional imaging is essential in diagnosis and evaluation of suitability for surgery. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are of similar sensitivity.

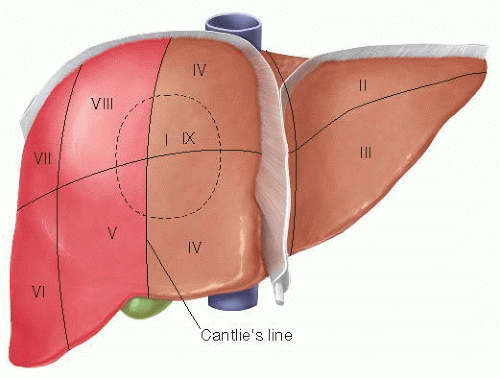

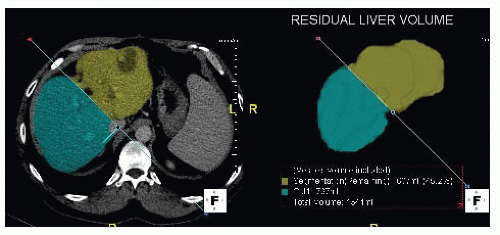

In a normal, healthy liver, a remnant measuring 25% of a complete liver volume should constitute sufficient functional liver. However, in a damaged or cirrhotic liver, a remnant of greater than 40% is recommended. When performing a right hepatectomy, the remnant hemiliver is usually of adequate size in a healthy liver. In most cases, this does not require formal volumetric analysis; however, liberal use of volumetry should decrease the risk of postoperative hepatic insufficiency (FIG 2). In the event of marginal remnant volume, preoperative portal vein embolization on the side of resection can induce hypertrophy of the planned liver remnant.

Hepatic steatosis can be evaluated by comparison of the densities of liver and spleen on noncontrast images. Alternatively, biopsy of the liver can provide quantitative assessment of fat content. Significant steatosis can suggest a liver remnant at risk of postoperative failure. Current practice would advocate strategies for preoperative hypertrophy to ensure a remnant that is at least 30% of the native volume of the liver.

Patients with history, laboratory, or radiographic findings concerning for significant hepatic injury or dysfunction are referred for invasive testing of the liver, such as transjugular measurement of the portal pressure gradient (normal <5 to 8 mmHg) and biopsy (to evaluate steatosis or cirrhosis).

Patients with evidence of decompensated cirrhosis (Child’s B and C) are not candidates for right hepatectomy but may be candidates for liver transplantation in clinical settings of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, or metastatic neuroendocrine tumors.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The indications for hepatectomy include diagnostic uncertainty, symptomatic benign lesions, and malignancy (Table 1).

The strongest evidence for hepatic metastasectomy shows that R0 resection prolongs survival and is potentially curative for colorectal carcinomas and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative cross-sectional imaging should be reviewed with skilled radiologists before surgery and be available throughout the procedure.

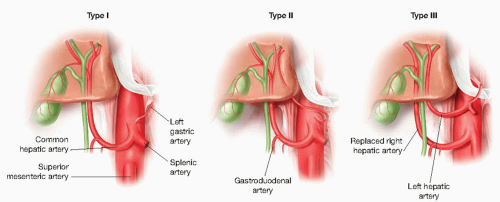

Vascular, particularly hilar, arterial anomalies are common. Inadvertent injury at surgery may be prevented by thorough study and multiplanar analysis (FIG 3).

Three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction is not mandatory, but understanding of all the lesions and their relation to hepatic and portal venous structures is imperative. This should be combined with intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS).

For postoperative pain control, preoperatively placed epidural catheters, administered by a dedicated pain service, have been shown to be effective and impact respiratory complication rates.

Low central venous pressure (CVP) anesthesia is a cornerstone in reducing blood loss. To maintain low CVP (5 to 8 mmHg), good communication with the preoperative nursing and anesthesia teams is critical.

Table 1: Indications for Hepatectomy

Diagnosis

Premalignant disease

Focal nodular hyperplasia vs. hepatocellular adenoma

Hepatocellular adenoma

Biliary cystadenoma

Symptoms

Malignancy

Hemangioma

Simple cysts

Metastasis

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Benign disease

Cholangiocarcinoma

Refractory abscesses/cholangitis

Severe hepatolithiasis

Patients receive prophylactic antibiotics due to transection of the biliary tree (clean-contaminated surgery). The authors consider cases with an indwelling biliary device as contaminated.

Patients undergoing hepatectomy are at high risk for venous thromboembolic (VTE) disease due to age, presence of malignancy, and complex, long major abdominal surgery. Unfractionated heparin is given subcutaneously prior to induction and redosed every 8 hours as needed.

Positioning

Supine with arms abducted

TECHNIQUES

INCISION AND EXPOSURE

A right hemihepatectomy can be performed through a subcostal, chevron, or midline incision. It is the authors’ preference to operate through a midline incision.

A fixed traction system is employed with emphasis on the cephalad and lateral retraction of the costal margin to provide adequate exposure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree