LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To convey the pitfalls of assuming professionalism is a character trait.

To articulate the advantages of viewing professionalism as a multifaceted competency.

To explain the connection between personal wellbeing and professional resiliency.

To describe skills set needed to maintain professionalism in stressful circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

Joan kicked off her shoes and sank into her chair. It had been such a bad day. She has been on a clinical rotation for only a week and already she is thinking that she won’t be able to be a good doctor. It’s not taking the history or doing the physical examinations or even fielding the rapid-fire questions on rounds. It’s the professionalism issues that worry her. Almost every day this week she has seen doctors and nurses lose their tempers with one another— responding sarcastically, leaving in anger, and yelling at the team for a bad outcome that wasn’t their fault. Even worse, today, she found herself getting really angry at a patient who just refused to talk with her and then complained about her on rounds. She actually went back after rounds to tell him off, but fortunately his granddaughter was in the room, which made her think twice. She came into medical school to be a caring and compassionate physician and thought that the professionalism stuff would be easy—you know, just follow the golden rule and you will be fine. She realizes now that all of those professionalism lectures in the first 2 years were there for a reason—to drill into her head the need to work to ensure that she is the doctor her patients need her to be. But she had no idea it would be so hard— just reminding people to be professional doesn’t seem to be enough. How do the best doctors do it?

Professionalism is at the heart of all that we as physicians aspire to be. When we enter medical school, we imagine ourselves calmly and compassionately ministering to the suffering by selflessly using our carefully honed skills and knowledge to determine and carry out the best treatment plan possible for the patient in front of us. In return, we would be appreciated and feel gratification.

In today’s environment, professionalism appears to be under threat. On the national level, reports of unprofessional physician behavior—ranging from overt crimes, to abuse of power, to conflicts of interest—are easily disseminated using today’s web-based communication tools. Each sensational story raises questions about why such a person was allowed into the medical profession and why the profession itself hasn’t fulfilled its obligation to oversee its members and deal with the rogue physicians who are the subject of national headlines. At the state level, medical boards receiving complaints about physicians have few options other than to sanction with license suspension or revocation and publicize the names of the transgressors. At the institutional level, hospitals are struggling with physicians who exhibit disruptive behavior, like those witnessed by Joan. Repeated instances of ineffective interprofessional communication; disrespect for peers, patients, and trainees; and failure to adhere to evidence-based safety practices are tied to high staff turnover, low employee morale, and poor safety cultures (Hickson et al, 2007). At the individual level, medical students who experience a disconnect between classroom lessons on professionalism and the behaviors they witness in the clinical environment become cynical and lose empathy (Hafferty & Franks, 1994; Testerman et al, 1996) (see Chapter 8, The Hidden Curriculum and Professionalism). Residents and practicing physicians experience burnout as they find themselves ineffective in their daily work (Shanafelt et al, 2002; Billings et al, 2011; Zwack & Schweitzer, 2013).

IS PROFESSIONALISM A CHARACTER TRAIT?

The conventional approach to professionalism—an assumption that professionalism is a character trait of the good physician—reinforces the problem. With this approach, our role as educators and peers is to screen people entering the profession to make sure that they possess that trait, then to monitor them over time and remove them if they exhibit behaviors that suggest that the professionalism trait either never was or no longer is present. This disciplinary approach to professionalism often leads to inaction on the part of physicians who witness trainees or peers behaving in a manner incompatible with our professional values (Burack et al, 1999). Physicians may not know how to intervene to fix a problem that is linked to a trait rather than a competency. They may be fearful that the disciplinary sanction that may result if they intervene or report a colleague is too extreme for the behavior they witnessed. They may be also be fearful that their own behavior is at times not compatible with professionalism and worry that they too may someday be subject to a high stakes intervention. As a result, physicians are often silent when they witness colleagues who demonstrate unprofessional behaviors.

PROFESSIONALISM IS A COMPETENCY

A new set of assumptions is emerging as a useful paradigm to help all healthcare professionals deliver on the promise of professionalism for our patients (Lucey & Souba, 2010) (Table 2-1).

| Aspects of professionalism | Old assumptions | New assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Professionalism as a competency | Professionalism is an attitudinal competency based on character traits present at the start of medical school. | Professionalism is a multidimensional competency with elements of knowledge, attitudes, judgment, and skills. |

| Professionalism in an individual | Physicians who lapse are unprofessional. The competency of professionalism is dichotomous and fixed at the time of completion of formal education. | Lapses in professionalism can occur in physicians who are good professionals. The competency of professionalism follows a developmental curve from beginner to expert, and it is continuously shaped over the lifetime of a career. |

| Professionalism challenges | Challenges to professionalism are infrequent and unpredictable. | Challenges to professionalism are common and can be anticipated. |

| Response to a lapse inprofessionalism | The response to a lapse in professionalism is commonly punitive, relying on negative labels, sanctions, and the threat of removal from the profession. | The response to a lapse in professionalism should be pedagogical, using active, targeted coaching based on root-cause analysis of the lapse. Sanctions should be reserved for those who fail to respond to the pedagogical approach. |

| Role of the healthcare system | The healthcare system is simply the setting in which lapses in professionalism occur. | The organization and operations of a healthcare system can increase the likelihood that a lapse will occur. Changes in the healthcare system can support physicians as they strive to live out their professional values. |

| Responsibility for stewardship of professionalism | The educational system owns the primary responsibility for ensuring that physicians remain professional by selecting the right individuals and training them well. | The community of practicing physicians, inclusive of educational andhealthcare system leaders must assume responsibility for supporting, reinforcing, and guiding physicians to remain professional throughout their careers. |

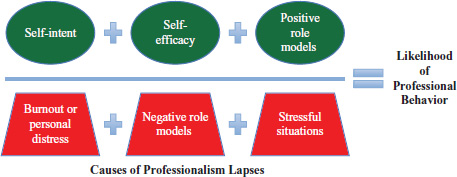

The practice of medicine is stressful and complex, and challenges to professionalism arise predictably on a daily basis. Physicians must be committed to living the values of professionalism. But rather than viewing professionalism as an immutable trait, we view professionalism as a true competency; a set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that can and should be the subject of professional development. Viewing professionalism as a competency means that we assume that transient episodes of unprofessional behavior are “performance lapses” rather than character flaws, and that we adopt an educational rather than a disciplinary approach to manage them. The role of educators and professionals within our environments should be to help build and sustain a commitment to professionalism by all within our community and to foster resilience in our students, our trainees, and our peers so that all may be “habitually faithful to professionalism values in highly complex situations” (Leach, 2004). This means not only ensuring that people intend to be professional (self-intent), but also that they have confidence that they can act in a professional manner (self-efficacy). The presence of positive role models who demonstrate professional behaviors reinforces and supports the ability of individual physicians to act in a professional manner. It is important to note that the likelihood of behaving in the desired manner decreases if people who the student admires conduct themselves in an unprofessional manner or if the context in which the behaviors are expected is too challenging for the individual’s skills (Regehr, 2006; Hafferty & Franks, 1994). Figure 2-1 illustrates the relationship between these variables.

CAUSES OF PROFESSIONALISM LAPSES

Dr. Hernandez, the associate program director, sighed. He had just fielded a complaint from one of the ICU nurses who said that Dr. Miller, one of his residents, screamed at her in the middle of the night when she notified him that an error had occurred and a critically ill, 24-year-old patient with bacterial meningitis had missed a dose of antibiotics. Shaking his head, he wondered what to do. “If they don’t know how to be nice to people by the time they are 26, how am I supposed to teach them? Who let this type of a person into medical school anyway?”

Dr. Hernandez’s view of a professionalism lapse is common, and his sense of futility is understandable. However, a closer analysis of this professionalism lapse might help turn this lapse into a learning opportunity for the resident in question by pinpointing the competencies that are needed to maintain professionalism in our complex, and at times stressful, healthcare environment.

In our view, few physicians are inherently unprofessional. Instead, professionalism challenges can lead to professionalism lapses if the individual in question lacks the knowledge, judgment or skills to be able to successfully navigate those challenges.

In this brief case, one can envision a resident on call covering for many patients. He is managing a patient who is doing poorly, and along with the nurses and other health professionals in the intensive care unit, he is trying desperately to save this young patient’s life. It is likely that he is tired, possible that he hasn’t eaten, probable that there are other sick patients for whom he was responsible, and conceivable that an ill patient close to his own age is evoking some feelings of transference. He may be worried that he will be held responsible for the error, and the fact that it happened on his watch may reflect poorly on his reputation. He responded to the nurse in the heat of the moment in a manner that was both unprofessional and understandable.

DEFINITIONS Professionalism challenges:

situations that may make it difficult for an individual physician or physician in training to remain true to professionalism values.

Professionalism lapse:an error in judgment, skill, or attitude that leads an otherwise competent physician or physician-in-training to behave in a manner contrary to established professionalism norms.

The purpose of this analysis exercise is not to justify or excuse the behavior. If Dr. Hernandez simply attributes the resident’s behavior to a stressful situation and chooses not to counsel or intervene with the resident, the resident will not get the opportunity to learn from the encounter. Bad behavior that is not corrected is likely to be repeated. Similarly, simply reminding the resident that he shouldn’t yell at the nurses and not to do so in the future is unlikely to be successful in the long term. What is needed is a strategy that helps the resident to understand why he responded unprofessionally, how he can work to develop skills to ensure he can respond more professionally when he faces any another similarly challenging encounter in the future, and why remaining professional is so important to the healthcare environment and should be important to him.

Dr. Miller has felt terrible since he yelled at the ICU nurse. He knows he shouldn’t have taken his frustrations out on her but he felt like he couldn’t help it. Now Dr. Hernandez has called and said he wanted to talk with him about his interaction with the nurse. Dr. Miller worries that his poor handling of this situation will damage his reputation for good.

Dr. Miller’s feelings are also typical. Nobody feels good about acting inappropriately and yet, most of us have done this in one way or the other. Typically, we hope the episode will go unaddressed and be forgotten. We fear, as Dr. Miller does, discussing the behavior with our peers or supervisors. However, a training setting can develop a culture that fosters feedback and learning—even if at times these conversations can be difficult. If Dr. Hernandez provides feedback and support to Dr. Miller, this can be a critically important learning experience both in this situation and for his future ability to handle these types of situations.

DEFICIT NEEDS AND PROFESSIONALISM CHALLENGES

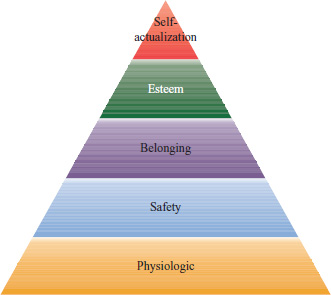

Behaving professionally may be sometimes counter to human nature. Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory states that humans will behave predictably to fulfill, in sequence, physiologic needs for food and shelter, safety needs for security and stability, belonging needs for friends and family, and self-esteem needs for achievement and recognition before they can behave in a self-actualized manner (Bryan, 2005) (Figure 2-2).

Despite this awareness of instinctive human behavior, we expect medical students, residents, practicing physicians, and other health professionals to behave in a self-actualized manner despite having unmet deficit needs. Dr. Miller is expected to respond calmly, respectfully, and in a problem-solving mode despite being tired and hungry (physiologic needs unmet), alone (belonging need unmet), and insecure (self-esteem need unmet). Work in cognitive psychology also reminds us that when human beings feel their ability to meet their essential needs is threatened, they respond predictably with fight or flight reactions. In the clinical environment, fight reactions are represented in yelling, intimidation, sarcasm, and physical violence. Flight reactions include ignoring questions, refusing to answer pages, and other forms of passive-aggressive behavior.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree